Like many of us, Charlie Brown and his not entirely devoted dog, Snoopy, were always looking for ways out of the difficult and sometimes ugly world they lived in, through fantasies of sports stardom (such as actually winning, for once, a Little League game) and World War I dogfights with the Red Baron conducted from the top of a bullet-riddled kennel. As Blake Scott Ball argues in his perceptive survey of the longest-running individually drawn and written comic strip of all time, the success of Peanuts had something to do with a quality it shared with “good ol’” Charlie Brown himself: “wishy-washiness.” “I lean over backwards to keep from offending anybody,” Schulz told a reporter near the end of his remarkable 50-year run. The daily enjoyment of reading Peanuts (unlike reading Walt Kelly’s Pogo or Trudeau’s Doonesbury) often felt like a collective national retreat from irksome American reality.

The strip, one critic has pointed out, never provided a “topical home” for the national traumas of Schulz’s lifetime: “Hippies, Vietnam, Watergate, Iran-Contra, CIA spy scandals, impeachments, elections.…” Peanuts existed in a hazy zone between Schulz’s imagination and the world that he and his readers actually lived in. It joyously provided a free space in which to play and laugh even when the real world didn’t seem very playful or funny at all.

For most of his career (until a series of Snoopy-as-soldier D-Day remembrances in the mid-1990s), Schulz rarely depicted or made references to the perilous world we live in; instead, he focused his narrative eye on topics that might existentially stress out children (and their parents) but wouldn’t physically harm them all that much. For all the angst and ennui they suffered—lying awake in the night wondering about past failures and future possibilities—nobody in the Peanuts gang ever suffers from serious disease, poverty, debilitating war wounds, or painful separation from loved ones—unless that separation leads to a quick and eventual reunion. (See: Snoopy, Come Home!)

And yet for all Schulz’s reticence about addressing significant world events, his readers couldn’t seem to stop finding special significance in Peanuts, whether they saw in it feel-good, Hallmark-card–like philosophy (à la Happiness is a Warm Puppy) or religious parable, or a reflection of the author’s views on war, feminism, and abortion rights. Garry Trudeau (famous for Doonesbury, a strip that wore the political world on its sleeve, which Schulz “despised”) felt that Schulz’s vision “vibrated with ’50s alienation,” and at least one reader claimed that Charlie Brown represented “the existential situation of the Beat Generation.” After all, like many lost souls, poor beleaguered Charlie Brown often wondered about his purpose in life. Some regarded this anxiety as the fate of any intelligent human being; others saw it as a commentary on what one historian called the “age of fear and suspicion.” Peanuts had to mean something. Didn’t it?

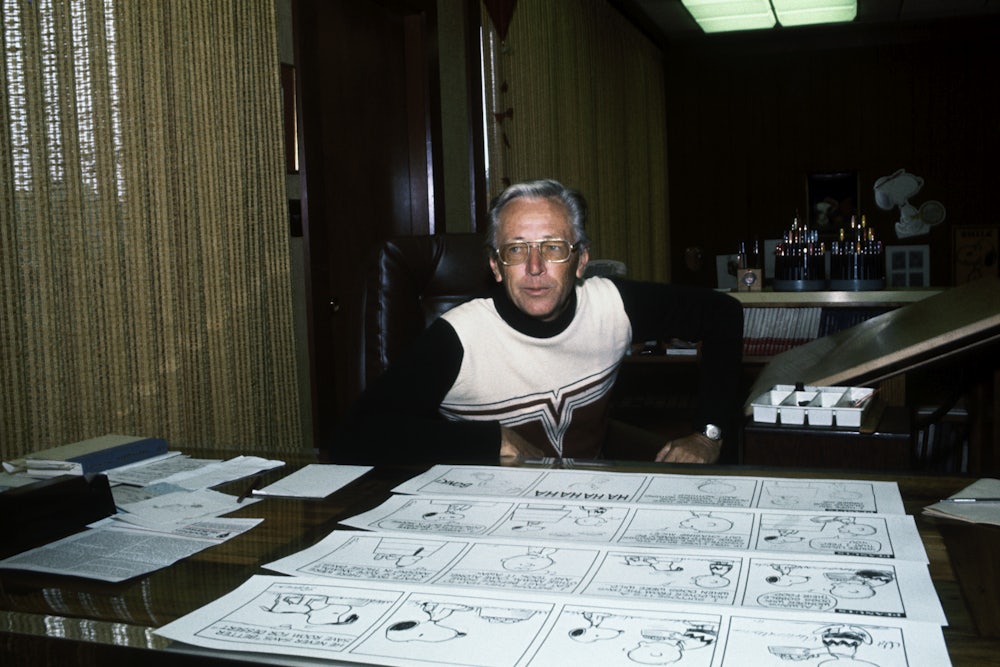

Raised in the Twin Cities during the Great Depression, Charles M. Schulz was, like Charlie Brown, the son of a barber who owned his own shop. With his father, Schulz shared an early affection for the newspaper comic pages. (His nickname, “Sparky,” was derived from the horse Sparkplug in Barney Google.) He lived a relatively sheltered life until he was drafted in 1942 and eventually saw action during the liberation of Dachau. As he later recalled the most stressful period of his life: “The three years I spent in the army taught me all I needed to know about loneliness.”

After his war experiences, Schulz became a devout evangelical Christian; he spent a large part of his life reading and annotating a Bible that he kept in his office and enjoyed recounting his attendance at one of Billy Graham’s first crusade meetings at Madison Square Garden in the mid-1950s. Shortly after the war, he acquired his first job, as a letterer at Topix Comics, which produced Catholic comics, where he began trying out his particular brand of low-key, domestic humor, focusing on the unspectacular concerns of suburban Americans: consumerism, family holidays, pets, school friends, and, most of all, the pleasures and perils of childhood sports.* In a typical line, in an early single-panel cartoon in “Just Keep Laughing…” one little boy tells a little girl: “Y’know, Judy, I think I could learn to love you if your batting average was just a little higher.” The relationship between romantic love and the love of sports would infuse Schulz’s imagination for the next half-century.

From the late 1950s, when Schulz began hitting his creative stride, Peanuts rapidly outgrew its rudimentary early strips and premises, and the characters began to develop complex personalities and relationships—just as the soon-to-be phenomenon of Snoopy developed sentient thought bubbles, along with several fantasy careers as an erstwhile novelist, World War I Flying Ace, lawyer for hire, and even, on rare occasion, a former guard dog. As Schulz’s fictional universe grew more complex, he was applauded by a wide variety of theologians, politicians, and child psychologists, from Timothy Leary to Ronald Reagan to J. Edgar Hoover (whose “approval” Schulz found “very flattering and very thrilling”). Even that wishy-washiest of contemporary political figures President Obama would eventually write: “I grew up with Peanuts. But I never outgrew it.”

Soon the Peanuts characters began clambering out of the daily strips and spilling over into the world they were already transforming with their peculiar vernacular. Terms like “security blanket” (originally coined to refer to military secrecy) and sayings such as “Good grief!” or “Happiness is a warm puppy” found their way into common parlance; there was a Broadway musical, feature-length movies, and a series of special event television cartoons (A Charlie Brown Christmas in 1965 and It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown in 1966). Snoopy’s big “banana nose” began filling up short-timer calendars in Vietnam and adorned the fuselages of fighter jets and helicopters. And the whole gang began appearing in print and multimedia advertisements for everything from Ford Falcons and auto insurance to environmental “awareness” and sex ed. A theme show of the 1970s Peanuts craze might well have been called, It’s Your World, Charlie Brown! Don’t Blow it!

But by the 1980s, some believed that Schulz did blow it, especially when his strip seemed tame in comparison to the more jagged, cacophonous suburban horrors of The Simpsons. And the cultural iterations of Charlie Brown and his gang began to seem increasingly bland and conventional.

In its heyday, it was hard not to think that Peanuts was more meaningful than it was—and this has something to do with Schulz’s unusual (for the time) visual and verbal style. When Peanuts premiered on the front page of The Denver Post on 2 October, 1950, it appeared in stark contrast to the other comics—such as the escapist, romantically lush landscapes of Alex Raymond (Flash Gordon) and Hal Foster (Prince Valiant), or the richly drawn action-man heroics of Milton Caniff (Terry and the Pirates and Steve Canyon). Even the strip that inspired Schulz as a young man—George Herriman’s inimitable Krazy Kat—was a more surreal, Dada-esque affair than a small tribe of round-headed children playing in schoolyards and sandboxes.* (“I always thought if I could just do something as good as Krazy Kat, I would be happy,” Schulz recalled. “Krazy Kat was always my goal.”) Peanuts felt like a part of the world most Americans actually inhabited, even while it was creating a disengaged reality all its own.

Schulz never liked the title of Peanuts; it had been decided by a committee of newspaper editors as a way of identifying the strip as a predictable, bite-size set of four daily uniform panels, a sort of endlessly repeatable snack. (For the rest of his life, Schulz disliked the title so much that he often introduced himself as the person who drew “that comic strip with Snoopy in it.” The strip’s simple lines and backgrounds, the almost anonymous nature of its characters and even their names (“Charlie Brown,” “Shermy,” and Lucy”) seemed childlike and innocent.*

But soon the complicated nature of these not-quite-childlike personalities began generating an appeal to both children and adults, who could each read the strip in different ways. The simple panels invited readers to fill in the gaps—and Schulz gave them all the room they needed. They imagined emotional depths for its characters; they imagined the inner voice of a dog whose commentaries on life seemed both anthropomorphically believable and wild; they imagined the offstage parental figures who were rarely heard and never seen; and they imagined the vast natural spaces that divided houses, neighborhoods, and schools. (A late addition, Snoopy’s desert-happy brother Spike, spends most of his time imagining conversations with a humanlike cactus somewhere in Needles, California.)*

And when Schulz’s characters commented on actual things or events in the world, such as “H-bombs” and “fallout,” these were never the same nuclear nightmares that haunted Cold War–era newspapers and science fiction movies; they were more like childhood approximations of what these confusing words might mean to someone who didn’t understand them. When Linus mistakes falling snow for nuclear “fallout” in an early Sunday strip, readers could accept this mistake almost as a way of disarming the actual, horrifying concept of nuclear war (and at a time when most schoolchildren were going through school drills about what to do in the event of a nuclear attack). Peanuts envisioned a world that was bearable even when it addressed elements of the real world that were not.

While Peanuts is today often remembered more for its animated television shows, which continue playing through our holiday seasons, these are toothless misrepresentations of Schulz’s particular genius. In fact, it’s hard to imagine a more un-Peanuts-like version of Peanuts than these animated cartoons. Using actual children to supply the voices of these “hypothetical” kids (and giving up altogether on representing the marvelously articulate inner life of Snoopy), they almost entirely erase the beauties of Schulz’s world. After all, the children in the daily strip weren’t quite children; that’s what made them so interesting and malleable in the imaginative life of each reader. They were sort of like children (and dogs) who suffered from adult-like, maturely-reasoned concerns.

Schulz’s restrained, unelaborate visual eye—combined with the simple-featured characters (Charlie Brown in his jagged-line-emblazoned T-shirt, Linus in his striped shirt and short pants, etc.) and dialog that was always a bit more elevated than both the characters and their readers—made the series reverberate with an intelligence and profundity that the author probably didn’t possess himself. And then there were those occasional little flourishes that suggested something significant must be happening—such as the appearance of a frizz-topped yellow bird named “Woodstock.” That must mean something in the 1960s and 1970s, right? But often these little suggestions of a metaphorical meaning were simply occasions for the readers to invent meanings for themselves.

As the Peanuts meta-verse extended into all areas of American culture and commerce—adorning children’s pajamas, barbecue aprons, and automobile bumper stickers—the parable-like nature of Schulz’s fictions began to seem almost exasperatingly clear. There were times when Peanuts seemed to mean something different to everybody who read it. And that meant readers could respond in a variety of different ways, and with equal enthusiasm and confidence, to the same strips. After all, aren’t we all tired of hearing people compare themselves or others to Lucy holding the football for Charlie Brown and pulling it away at the last minute, year after year after year? The Peanuts strips invite all of its readers to engage in these types of comparisons. Charlie Brown and his friends became us, one way or another.

But as Ball relates, while Schulz may have sought to avoid the political world, the political world never let him get away with it for very long. Some readers tried to use Peanuts in support of their own beliefs and ideologies (such as when anti-abortion protesters latched onto a strip in which Linus asked Lucy if people, before deciding to limit the size of their families, should consider the possibility that there might be “a beautiful and highly intelligent child up in heaven waiting to be born”). Even Snoopy’s imaginative adventures as the WWI Flying Ace were interpreted as a commentary on the Vietnam War. (Mort Walker, the artist behind Beetle Bailey, thought the images of a bullet-riddled doghouse in the late 1960s would end Schulz’s career.) Not long after he began visiting veterans at a San Francisco hospital, Schulz chose his Christmas Day 1968 strip to conclude with Snoopy decrying: “I’m tired of this war!” It was as if even Snoopy couldn’t imagine a world without Vietnam, or the public’s exhaustion with it.

It’s hard to believe we once lived in a much simpler country where television producers actually worried about the potential ramifications of Linus reciting a brief line of scripture during a church nativity play in A Charlie Brown Christmas. (Isn’t that what children do in nativity plays?) Or how resistant some Southern newspapers might be to the blithely abrupt appearance, in 1968, of Franklin (the first Black character in a nationally syndicated American comic strip), sitting near Peppermint Patty in an otherwise all-white grammar school at a time when the Supreme Court was handing down desegregation decisions. It’s not clear if Schulz intended to send signals of support for desegregation (though Ball argues that he did), but when a Southern newspaper editor asked him to redraw the character, Schulz claimed to have fired back: “Either you print it just the way I draw it or I quit.”

Even when Schulz expressed support for changes in social life and public policy, he couldn’t always make it work creatively. The much-heralded and debated early appearances of Franklin didn’t deliver a character that Schulz could work out how to use, and Franklin soon receded into the background cast of minor characters. “I’ve never done much with Franklin,” Schulz apologized in the late 1970s. “I don’t know what it’s like to grow up as a little black boy, and I don’t think you should draw things unless you really understand him.”

While Franklin never took off as a character, Peppermint Patty did. Her name was inspired by the popular foil-wrapped candies, but her personality emerged from Schulz, like Athena from Zeus’s head, full-blown. Patty was a latchkey kid, raised by a single father, who loved sports and hated school, and when she made her first appearance on August 22, 1966, she introduced herself as a tough, sporty girl who wanted to join Charlie Brown’s team and “solve” his “baseball problems.” She went on to become one of the most omnipresent and continually interesting characters in the strip, eventually presenting the most consistent political argument in Peanuts that seemed to address Schulz’s own support for Title IX reforms in how public school sports were financed.

But to the end of his life, Schulz made almost every strip, and almost every utterance of every character, consistent with a comic fictional world where boys, girls, and dogs of every stripe wrestled with abstract enormities, such as unrequited love, losing baseball games, and gazing up with a sense of vast loneliness at a night sky filled with unutterably perplexing stars. Over the 50 years of its existence, it’s rare to find a single Peanuts panel in which any character serves as a mouthpiece for Schulz’s editorial opinions: His characters are always—whether analyzing scripture (Linus), or bullying their younger siblings about what TV programs to watch (Lucy), or devoting their writerly life (Snoopy) to collecting rejection slips—consistent with themselves and the imaginary world they inhabit together.

Near the end of his life, Schulz confessed to being (like his barber-shop-owning father) “always a Republican,” who worried that even a moderate like Bill Clinton “wanted to run so many different things”; he begrudgingly characterized himself in one late interview as a “liberal,” who was “overjoyed to have dined with Ronald Reagan.” But the confession shouldn’t have been surprising. While Schulz was a generous soul, he was a far from angry one; his characters often expressed consternation about the world, but they were almost never angry about anything beyond their immediate frames of interest, such as what television program to watch, or the fact that their supper had grown cold. They wanted to make “liberal” adjustments to their world, but they rarely sought radical reforms.

What did surprise (and continues to surprise) good readers is how adroitly Schulz managed to write sympathetic, character-driven stories about a bunch of kids and animals all the way up to the end of his life—and eventually managed to experiment beyond the old four-frame that had so long constrained him. In his final panel, published only hours after he died on February 12, 2000, Schulz even stepped out from behind the authorial stage and declared: “I have been fortunate to draw Charlie Brown and his friends for almost 50 years … how can I ever forget them.” Like his readers, Schulz had lived a life with his characters the same way many of us lived with them—as imperfect personalities who were, for the most part, predictable. Except, of course, on those days when they weren’t.

* A previous version of this story misstated Schulz’s work at Topix Comics, when he read Krazy Kat, and where Snoopy’s brother Spike lived. Also, the character Shermy did not go by Sherman.