When Lionel Trilling dismissed America’s conservative intellectual tradition as a series of “irritable mental gestures,” it’s a safe bet that he had people like Robert Welch in mind. Welch, the irascible candy executive who founded the John Birch Society, spent an enormous amount of time and energy lovingly crafting irritable gestures in the minds of his hard-right acolytes, from the conviction that the New Deal was a Communist plot to the claim that Dwight D. Eisenhower was also a Communist. Over time, Welch and the Birchers launched a host of other woolly propositions about American public life. Their claims that the corporate media hates capitalism and their complaints of a secular assault on the traditional family are now familiar refrains in today’s Trumpian right.

Over Welch’s long career, his penchant for conspiracy eventually outgrew the idea of the grand Communist plot for world domination; the scheme of forcible Soviet control over all available means of production was in fact “only a tool of the total conspiracy,” Welch concluded. The real puppet masters—whom Welch came to call simply “the Insiders”—were a heady cabal of East Coast cultural and financial elites, the globalist power brokers of the Bilderberg Group, the grand strategists of the Council of Foreign Relations, and of course their obliging surrogates in the mainstream press.

For Trilling and the other apostles of America’s postwar liberal consensus, Welch and the Birchers were a terminally backward-looking movement, ill equipped for the complex challenges of sober governance and distrustful of anything resembling modernity and progress. In this analysis, the reactionary right of the 1950s and beyond was profoundly maladaptive, steeped in cultural resentments, status anxieties, ethnic and religious bigotries, and grandiose conspiracy-mongering. The reactionary right sought to restore a world order that was, in essence, everything that the modern world was not: proudly Christian and Americanist over against a doubt-ridden regime of science-bred skepticism; morally Manichean in opposition to a new age of statecraft that embraced agonizing complexity; culturally confrontational and traditionalist in an era of upheaval in the universities, the press, and the country’s civic life writ large.

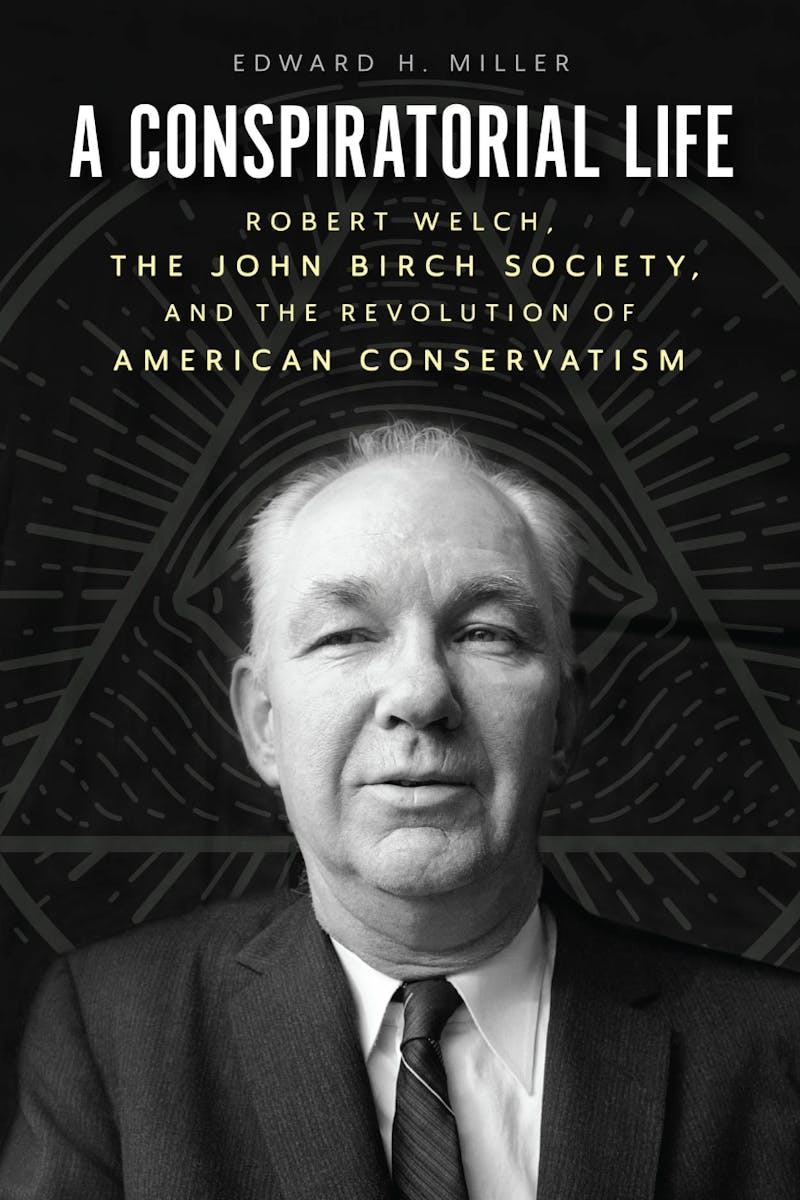

Yet on the far side of the midcentury liberal consensus, it’s clear that figures like Welch were much closer to the emerging ideological mainstream than any Cold War liberal could have imagined. In his new biography of Welch, A Conspiratorial Life, Edward H. Miller makes a provocative and persuasive case that Welch was a vanguard figure rather than a retrograde one. The Birch society was the first major group on the right to pioneer modern culture warfare, with committees opposing the Equal Rights Amendment, abortion, high taxation, and sex education. And once Ronald Reagan—who drew heavily on Bircher ideas, though without any formal affiliation with the group—ascended to the presidency in 1981, Welch’s organization became known “for its espousal of any issues that the Reagan revolution … cared about.”

In the decades since, a series of national political leaders have embraced and modified the hard-core Bircher gospel to the point where it has become the stock-in-trade messaging of the Republican Party. Welch, who died in 1985, would doubtless relish the rise of a baldly conspiracy-obsessed twenty-first-century right, intoning its grievances against a “deep state” and bruiting the notion of corrupt power elites’ complete treasonous control of the electoral system. Yesterday’s maladaptive crank has become today’s defender of the true and pure right-wing creed; whereas Robert Welch toiled in the mocked and marginal fringe of the “paranoid style,” today scores of prominent GOP leaders—from Josh Hawley and Tucker Carlson to J.D. Vance and Marjorie Taylor Greene—proudly wave the Bircher standard of ultrapatriotic elite-baiting and victimhood.

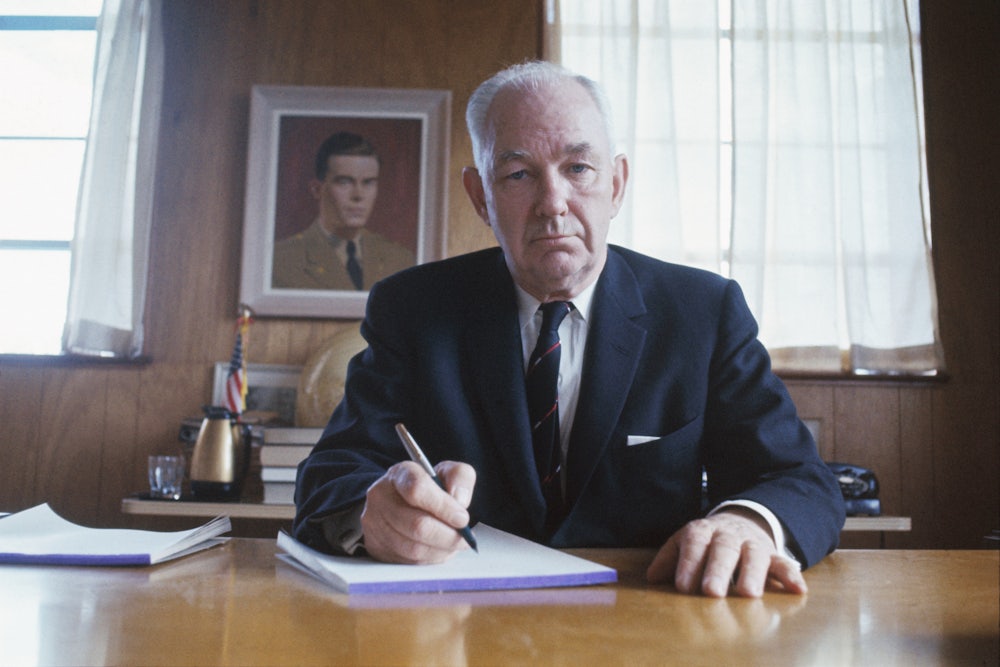

There was nothing in Robert Welch’s early life to mark him as such an influential prophet of right-wing reaction. The eldest son of a long-established farming family outside of Elizabeth City, North Carolina, Welch stood out mostly for his extreme intellectual precocity. At 12, he “became the youngest student ever to enroll at the University of North Carolina,” Miller writes, and studied widely, concentrating on math, philosophy, German, French, and poetry. After he graduated at 16, he enrolled at the U.S. Naval Academy, narrowly missing service abroad during World War I. The regimentation of Navy life didn’t sit well with the teenager, however—Miller describes the young Welch as a “Huckleberry Finn” and “a free spirit with a hint of adventure and mischief”—so he contrived to be released from an officer’s commission.

After a short stint as a versifying columnist composing “headline Jingles” for the Norfolk Ledger, Welch landed in Harvard Law School—then a bastion of Progressive-era philosophy and jurisprudence. The school’s pronounced left bent, particularly in matters of political economy, “trimmed Robert’s sails further to the right,” prompting him to embrace the laissez-faire, small-government outlook of 1920s Republicanism. He preached a classic conservative message of “austerity, self-denial and hard work” while professing nostalgia for a simpler “America filled with Americans of Anglo-Saxon and Northern European heritage.” As he countenanced the Progressive political theorizing of future Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter at Harvard, he realized the law wasn’t for him; he dropped out and launched a thriving candy business in Cambridge. Along the way, he married his Harvard sweetheart, Marian Probert, a Wellesley undergraduate who would be his devoted lifelong ally in the multifront battle against the specter of Communist subversion.

As Welch weathered the business storms of the 1930s, his politics grew more rigidly conservative. The onset of the Great Depression ravaged his business—he went into bankruptcy and reestablished himself as sales manager for the candy company founded by his younger brother James. (Robert retained a 10 percent interest in the profits of the company’s best-known product, the Sugar Daddy—a confection that Robert had first created at his old Oxford Candy Company perch—which would ensure him a comfortable lifelong income.) Like many businessmen of the age, Welch saw the New Deal as a stalking horse for an eventual socialist takeover of the United States; the same debased and demagogic vision of the political economy that had driven him from Harvard Law was now dictating the country’s economic policy.

But it was the specter of America’s entry into World War II that galvanized Welch’s emerging reactionary faith. He was an early adherent of the America First Committee—the anti-interventionist lobby so admired by famed aviator and Nazi sympathizer Charles Lindbergh.* (Miller notes that Welch, “unlike Lindbergh,” began speaking out against Hitler in May 1941, “to his credit”—without also noting that this was well into Germany’s European war effort.)

While the AFC never recovered from its association with Lindbergh, Welch claimed that the committee’s anti-interventionist crusade marked a key moment in his own coming of political age. Sounding very much like an anti-woke online demagogue, Welch claimed that the self-styled progressives castigating the committee’s indulgent posture toward Nazism “convinced me personally that there’s nothing so illiberal as the professional liberal.” In a typically coy flirtation with far-right agitprop, he went on to argue that “there is nobody so anxious to regiment all other citizens with their own particular brand of strait-jackets as the fellows who shout loudest that somebody else—Hitler in this case—is trying to put a strait-jacket on them.”

Nor was this Welch’s only anticipation of the present-day reactionary temper on the right; he and his anti-statist allies saw social democracy as the harbinger of eventual Communist takeover, and so loudly insisted that the U.S. was never meant to be a democracy and that the embrace of democracy spelled certain ruin. Recommending The People’s Pottage, an anti–New Deal tract by his friend Garrett Garrett as “required reading” for all Birchers, Welch hailed its clear-eyed account of “the Communist-inspired conversion of America, from a constitutional republic of self-reliant people into an unbridled democracy of hand-out seeking whiners.” A common refrain of the Bircher faithful was that America is “a Republic … not a democracy. Let’s keep it that way!”

Welch’s ardent right-wing allegiances were firmly in line with conservative sentiments—so much so that he mounted a 1950 campaign for the lieutenant governorship of Massachusetts, a surefire stepping stone, he reasoned, to a seat in the U.S. Senate and a career on the national political stage. His stump speech was based on his recent travels to England, where he professed to behold the dystopian future of an American society already well down the path toward socialism. England, he pronounced, was mired in overregulation and profound civic resignation—a land afflicted with a “general overall lack of ambition to do anything,” and where “patriotism has ceased to exist.”

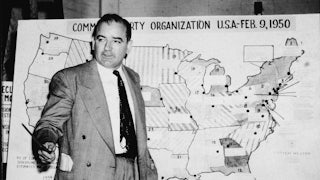

He lost the GOP primary badly to a former state treasurer and turned the bulk of his political energies going forward to grassroots organizing of the hard-core anti-Communist right. Seizing on several of Senator Joe McCarthy’s talking points—the foreign policy establishment’s alleged “loss” of China to communism in 1949; Harry Truman’s dismissal of hard-line anti-Communist General Douglas MacArthur from his post as commander of Allied troops in the Pacific during the Korean War; and the stalemated peace agreement in Korea itself—Welch formulated an explanation of virtually every world event as the handiwork of a Communist conspiracy. In 1954, he began working on a biography of the Christian missionary John Birch, slain by Communist forces in China during World War II—a killing that Welch alleged was covered up by the U.S. Department of State in order to conceal its own complicity with the rise of Communist rule in China.

Around the same time, Welch circulated an incendiary letter within the burgeoning network of far-right business conservatives, which eventually sprawled to more than 200 typewritten pages, alleging that Truman’s successor, Dwight D. Eisenhower, was likely a willing agent of Communist subversion. Like Welch’s other speculations, the letter—later published in book form as The Politician in 1963, with its most sensational innuendos carefully excised—piled inference on inference to marshal readers to the shocking “surmise” that the sitting U.S. president was “an actual Communist agent.”

This brand of evidence-free scaremongering was entirely in line with the McCarthy inquisition. But Welch was a far more disciplined messenger and on-the-ground organizer than the drunken and voluble Tailgunner Joe ever was. McCarthy was a hair-trigger demagogue; Welch was a talented writer and ambitious thinker who could make the most unhinged sort of claim appear both copiously researched and politically urgent. What’s more, he was a respectable leader of the American establishment, having logged a long tour as an executive for the right-wing business lobby the National Association of Manufacturers. So when Welch founded the John Birch Society in 1958, he brought the anti-Communist crusade a new aura of gravitas.

But this image makeover also required discipline of a different kind—a concerted effort to weed out the racist, nativist, and antisemitic sentiments of the old anti-interventionist American right, the very movement that had drawn young Robert Welch into political activism. Here, Welch’s record was at best mixed: He worked alongside avowed antisemites such as Slobodan Draskovich, who argued in the pages of the Bircher magazine American Opinion that U.S. participation in World War II had been a mistake; and collaborated with Russell McGuire, the editor of the American Mercury who cited the vicious, slander-filled work of antisemitic agitprop the Protocols of the Elders of Zion in the Mercury’s pages. For his own part, Welch lamented in his Eisenhower letter that the former general had helped convict accused German war criminals on the basis of “completely one-sided evidence.”

On matters of race, Welch was also a retrograde force. While he refrained from the uglier and more overt race-baiting of the right in the wake of the Supreme Court’s landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education, Welch was still very much a white son of the Jim Crow South, who allied himself with “unapologetic racists and diehard segregationists.” His conspiratorial mind prompted him to dismiss the civil rights uprising of the 1960s as simply another Communist plot seeking to exploit racial grievances to destabilize the American social order. Welch went so far as to suggest that the Birmingham protests in 1963—in which Sheriff “Bull” Conner infamously trained fire hoses and attack dogs on Black demonstrators and children—were a carefully orchestrated Communist photo op, staged for maximal network news coverage.

Tellingly, it wasn’t Welch’s persistent failure to read bigots out of the Bircher movement that lent it notoriety—it was, rather, the stolidly conspiratorial mindset of Welch and his growing mass following. William F. Buckley Jr. famously assailed the group’s obsession with secret Communist takeovers in an effort to render the postwar right intellectually respectable again. “There are … great things that need doing,” Buckley opined in the heat of his anti-Birch crusade in 1962: “the winning of a national election, the reeducation of the governing class. John Birch chapters can do much to forward those aims, but only as they dissipate the fog of confusion that issues from Mr. Welch’s typewriter.”

Buckley’s attempted “excommunication” of Welch from the conservative movement has become something of an origin myth for Buckley’s National Review, which has erratically taken up the challenge of arbitrating respectable opinion in a movement that has little patience for reasoned dissent or respectability. But as Miller correctly notes, reports of the death of Welch’s movement in respectable GOP circles were greatly exaggerated—thanks in no small part to Buckley’s own status as “one of the most prolific writers and most protective chroniclers of the story of movement conservatism throughout his lifetime.” Birchers remained in close touch with the grassroots activists of the right. Indeed, it was the most outlandish feature of the Bircher message—the specter of imminent Communist takeover in the U.S.—that lent the movement its popular staying power.

A host of liberal Cold Warriors indeed indulged the same fantasy of rampant Communist subversion. In 1961, Robert F. Kennedy claimed that “Communist espionage here in this country is more active in this country than it has ever been”; in 1963, his brother ordered J. Edgar Hoover to conduct surveillance on Martin Luther King Jr. because of suspected ties to Communist associates. While Joe McCarthy was long gone by the early 1960s, his legacy only spread further within the actual American body politic. “It could happen here, thought many Americans,” Miller observes. “Welch was saying that it was happening here. He was easy to believe.… In fact, he was never excommunicated at all.”

The John Birch Society thrived as never before in the wake of Buckley’s campaign to purge it from conservative ranks. The assassinations of JFK, Martin Luther King Jr., and Robert Kennedy—which Welch duly attributed to the deep-state machinations of the Communists and their Insider allies—produced a national mood of profound institutional and ideological distrust, in which conspiracy theorizing flourished. The racial backlash against the civil rights movement gained popular traction with coded pitches for “law and order” mounted by the George Wallace and Nixon campaigns in 1968. By 1971, the Birch society was claiming a national membership of between 60,000 and 100,000, and American Opinion had between 22,000 and 45,000 subscribers—though it’s common practice for political organizations to inflate such figures generously. Welch vowed to double those numbers in short order, and by 1976, the society “was a miniconglomerate of five corporations spending $8 million each year, with a staff of 240.”

In the post-Watergate and post-Vietnam political climate, Bircher thinking proved to be a rich mine of policy entrepreneurship, with the group forming ad hoc committees devoted to emerging issues on the front lines of the right-wing culture wars, from anti-obscenity and sex education measures to the campaign against the ERA to the burgeoning property tax revolts in California and other states. While the John Birch Society “did not create the Reagan revolution,” Miller writes, it was a key coalition partner at the grassroots level, working assiduously to “charge up many of the issues that dominated the Right’s rise to power.”

Ironically, the Birch society was reaching its zenith of political influence just as it was on the verge of institutional collapse. The group had plunged into serious debt, running up annual deficits of more than $1 million a year throughout the 1970s. Increasingly, Welch leaned on a single donor—the right-wing Texas oil billionaire Nelson Bunker Hunt—to keep the operation afloat. But when Hunt went all in on a scheme to corner the global silver market in the 1980s, he lost his fortune and was himself plunged into debt, having to rely—irony upon irony!—on a federal government bailout to be made somewhat whole. It was a grim crowning twist that a political revolution stoked by a conspiracy-obsessed businessman was ultimately felled by another paranoid businessman’s clumsily executed conspiracy. Upon Welch’s death in 1985, the society dramatically scaled down its operations in alignment with its straitened financial prospects.

Of course, one could well argue that by that time, the John Birch Society had achieved much of its founding mission anyway.* Ronald Reagan—a connoisseur of woolly conspiracy theorizing and apocalyptic biblical fantasies—was launching his second term in office on the heels of a historic landslide reelection campaign. Economic decline and ideological factionalism overtook the Soviet Empire, so much so that it would collapse under its own weight at the outset of the 1990s. And most vitally, the idiom pioneered by Welch—a heady compound of business martyrology, anti-elite grievance, ethnonationalist traditionalism, and shape-shifting cultural paranoia—became the lingua franca of American conservatism in the post–Cold War era.

We now live in a seemingly endless regress of irritable mental gestures from the right, and long before they took hold in Trumpian form, Robert Welch exhaustively demonstrated just how potent they could be. As Miller makes clear in this impressively researched and nuanced reconsideration of the modern American right, it’s Robert Welch’s world now—and we urgently need to find a way out of it.

* This article originally misstated Charles Lindbergh’s involvement with the America First Committee. It also misstated that The John Birch Society closed after Robert Welch’s death.