A few weeks back, I had the opportunity to teach a course on pathways to universal health care in the United States. To be clear, I have a very particular viewpoint on this—I literally co-wrote the book on Medicare for All. But I do my best to explain precisely why Medicare for All is head and shoulders a more efficient, effective, and yes, even politically plausible approach to solving our health care crisis.

Yet as someone who spends a lot of my time thinking about our health care system, I sometimes forget just how inured I’ve become to how broken it really is. And I was reminded anew by the disgusted reaction my students had to some of the most galling aspects of American health care we tend to take for granted. There were a lot of things they didn’t like, but none elicited quite the same reaction as the concept of a deductible.

Many of you are probably shuttering just thinking about your deductible. That’s because, if you think about it, a deductible is the paywall to get the insurance you already paid for. It’s like signing up for a streaming service and then having to pay extra to watch the movie you wanted, except that it’s thousands of dollars instead of $14.99. Health insurance companies use deductibles to kick costs back onto their beneficiaries, who may choose to pay less up front in premiums (what you have to pay every two weeks to have health insurance).

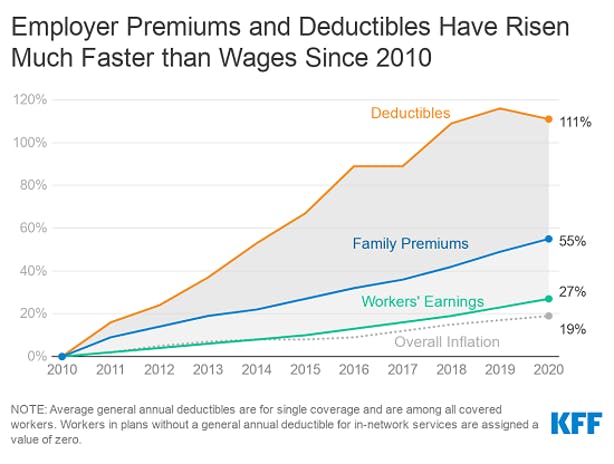

Deductibles have more than doubled over the past decade. One 2020 estimate put the median family deductible at $8,439. Considering the median American family earned $67,521 that same year, you can imagine the financial burden the deductible adds. It means that despite being insured, families are left paying out of pocket for every single health care interaction until they reach their deductible, which some families never reach. That’s on top of paying their premiums, which have increased by 55 percent over the past decade.

Given the rapidly increasing deductibles and the financial strain they put on families, the Kaiser Family Foundation calculated an annual “Deductible Relief Day,” the day when the average family finally pays down its deductible—like a bizarro, late-stage-capitalism family Black Friday. In 2019, Deductible Relief Day didn’t come until May 19—meaning that for nearly half the year, insured families had to pay out of pocket for their health care.

And those deductibles renew every year. So for millions of families, time is running out to fit in those last-minute health care needs. When the clock strikes 12 in just 35 days, on January 1, 2022, they’ll find their health care back behind the deductible paywall. It gives Black Friday a whole new meaning.

Health insurers argue that deductibles are a simple “cost-sharing” strategy—forcing patients to have “skin in the game” when it comes to using health care (beyond their actual skin, I guess?). Cost-sharing, they argue, prevents beneficiaries from using unnecessary, “low-value” health care. They point to an outdated 1970s-era experiment run by the Rand Corporation. It showed that patients who had to pay at the point of care did, in fact, use less health care and that their health outcomes were no different than those who did not have to pay. The health care they forwent, the study suggests, was “low value,” unnecessary care.

The experiment unlocked a Pandora’s box of cost-sharing in health insurance plans. But there’s an obvious difference between the deductible they tested in the Rand experiment and the ones health insurers charge today: They are astronomically larger.

Later studies have shown that deductibles don’t simply prevent “low value” care but all care. One study of employees of a company that switched its coverage from a zero-cost-sharing plan to a high-deductible plan found that after the switch, their employees even used fewer diabetes medications and got fewer colonoscopies—high-value health care, indeed. Another study found that women who were forced into a high-deductible plan delayed breast cancer screenings. Those who went on to develop breast cancer had their treatment delayed by an average of nine months!

High-minded blather about reducing health care costs aside, health insurers are charging high deductibles because they can. It’s a simple, easy, and now accepted way to fleece patients by forcing them to pay for their insurance twice. After all, if it were just about cost-sharing, insurance companies could end deductibles entirely and charge co-pays or co-insurance instead. If it was about forcing patients to have (more) skin in the game, these mechanisms that charge patients per health care use are arguably more effective. They charge patients for each use, rather than all or nothing depending upon the time of year, like deductibles do. But like cost-sharing in general, deductibles are simply about maximizing a bottom line.

For families around the country, that means racing the clock to get all the health care they need before the new year. Black Friday, indeed.