When President Biden went to Georgia this week to deliver a major speech on passing a voting rights overhaul, Stacey Abrams, the all-but-certain Democratic nominee for governor, decided to side with activists and not attend the speech. The explanation by Biden and Abrams was a scheduling snafu, but it was a clear snub by the Georgia Democrat and longtime voting rights icon. She opted to side with other activists in the state who skipped the speech, telling Biden that speeches weren’t enough.

Abrams didn’t need to establish her voting reform bona fides with anyone. This is the signature issue that she’s been fighting for her entire career in public life. Plus, Abrams is running for governor, and it wouldn’t help her campaign to appear beside a sitting president whose approval ratings are underwater to call for an overhaul they both know is a long shot. It’s clear that if Abrams is going to succeed in her bid to oust incumbent Governor Brian Kemp in 2022, she’ll do so through a massive registration and voter turnout push that she helped lead. Nothing about skipping the event would change that.

But for every other Democrat in a

gubernatorial race this cycle, that’s less true. Those other candidates don’t

have Abrams’s ties and long history with voting rights and voter registration

efforts. The truth is they have to run more conventional gubernatorial

campaigns where, yes, they talk about voting rights, but they also focus on

concerns voters feel are more pressing right now: fighting Covid and

inflation. And if Abrams wants to beat

Kemp, she will have to talk about those things, too. So the challenge for Democrats

running for governor this time around is to execute this balancing act as their

federal counterparts in Washington make a noble, but ill-fated, all-out push to pass one of two voting rights proposals.

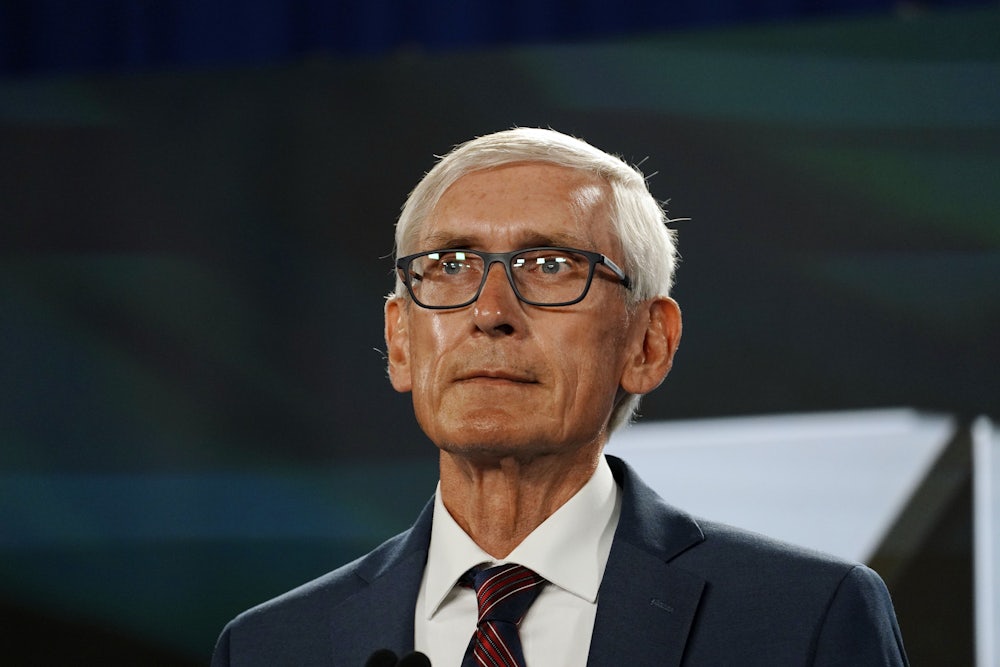

This will be particularly important in the five key states that will elect governors in 2022 and happen to loom as crucial swing states for 2024. In Arizona, a state with an open governor’s race, the Democratic and Republican primaries are shaping up to be messy and crowded affairs. In Michigan, Democrats are preparing for a cutthroat fight to defend incumbent Governor Gretchen Whitmer. The situation is similar in Wisconsin, where Governor Tony Evers was first elected by a small margin. The Georgia gubernatorial election may be one of the biggest turnout generators in American history. Abrams is running on the Democratic side, and incumbent Governor Brian Kemp has a Republican primary challenger backed by former President Donald Trump. And in Pennsylvania, Democrats are hoping they can continue Democratic control of the governor’s mansion after eight years of Tom Wolf.

As it happens, all of those states have Republican-controlled legislatures that are likely to stay in Republican hands come the end of 2022. For Democrats, it’s essential either to retain control of the governor’s mansions in those five states or gain control to block those legislatures from carrying out actions that will help Donald Trump overcome potential loss margins and be awarded those states’ electoral votes by whatever means.

Incumbents I interviewed say they are opting to make clear their stances on protecting voting rights and the need for their federal colleagues to pass new voting protections while focusing on more immediate, day-to-day issues in their states. “We have talked about the fact that governors are standing in the breach. Not only did we protect people from Covid when the Trump administration was being reckless, but we also protect our people from attacks on voting laws and other issues that Republican legislatures like to pass oftentimes for political reasons or pleasing the former president,” North Carolina Governor Roy Cooper, the current chairman of the Democratic Governors Association, said in an interview on Tuesday. “We’ve talked about that being an important part of why people need to pay attention to these governors’ races. I think where, nationally, Democrats have come up short is that we’ve not paid enough attention to governors and state legislatures.”

There are 36 gubernatorial seats up for reelection in 2022, 16 with Democratic incumbents. And of the states with a Democratic governor, six have Republican-controlled legislatures. The outcome of these races will decide the course of voting rights reform across the country and play a major role in the next presidential election, especially in a scenario where a renominated Donald Trump peddles unfounded claims of voter fraud.

“The biggest threat to democracy is the attack on voting rights by Republican governors with Republican legislatures,” Cooper said. “It’s the kind of thing I can stop and have stopped as a Democratic governor. We know that governors get things done.”

Yet those arguments aren’t always front and center for Democrats in the gubernatorial arena. Polling suggests that candidates have more of an incentive to talk about job creation or fighting inflation rather than threats to voting. A joint Associated Press–NORC Center for Public Affairs Research survey released a few days ago found that a wide majority, 68 percent, said the economy is a top concern while those surveyed listed other topics (like Covid-19 or anything under the “politics” umbrella) as less urgent.

In my interview with Pennsylvania Attorney General Josh Shapiro, the presumptive Democratic nominee for governor, he stressed that the efforts to recalibrate voting rules were very real and serious. “As the chief legal officer of the Commonwealth, we face really unprecedented attacks on our democracy,” Shapiro said. “Nearly 20 times before a single vote was cast, the former president and his enablers sued us to make it harder to vote. We won each and every one of those lawsuits.”

But when asked how one factors that into a campaign or runs for governor on that topic, Shapiro, who became a major target of Trumpworld in late 2020, added economic and pocketbook issues to the mix. “Well, let me be clear, I’m focused on the issues that matter most to Pennsylvania, including democracy, but I spend most of my time talking about how to grow our economy, lower taxes, lower costs for families,” Shapiro said. “We’ve got to protect rights: from the ballot box to the doctor’s office to criminal justice reform. I talk about how we need to shake up government and make it work for people and not against them. And all the while I talk about these issues that matter most to people, every single one of my Republican opponents—and I think, at last count, there’s like 13 or 14 of them—they keep peddling the Big Lie. And so I’ve made very clear that I would veto legislation that undermines voting rights. Something that they’re all pushing. And that’s the context in which it gets discussed in our campaign.”

Interviews with a number of Democratic governors, lieutenant governors, and gubernatorial aides reveal a strong agreement that fighting Republican efforts to change voting laws is a crucial role state Democrats will have to play going forward. However, they also show a lack of widespread discussion among governors on ways they can band together or at least trade notes on countering Republican moves to changing voting laws (sometimes governors do set up text chains and trade notes on a pressing issue that spans states).

In mid-December, Michigan Governor

Gretchen Whitmer and 16 other Democratic governors penned a letter urging

members of Congress to pass new voting protections (a push that is underway but

unlikely to produce much substance). But that coordination only goes so far. The

discussion among governors on voting rights has been limited, according to

multiple Democrat operatives and Democratic governors. Such coordination could

either help governors strategize about tactics for dealing with Republican

legislatures or help craft an effective national argument highlighting the

often-overlooked importance of governors in defending Democratic priorities.

Republican voters generally have an easier time understanding the importance of

governors and state legislatures.

In multiple interviews I conducted, governors proudly touted the veto authority they’ve used in this area. “I’ve made it public that I’ll veto any bill and it cannot be overridden unless somebody on the Democratic side sides with Republicans,” Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers said. “The things that the Republicans in Wisconsin are trying to do: It has nothing to do with democracy. It has to do with winning future elections by restricting access to the ballot box,” he said. “I don’t think it’s playing well, frankly.”

Evers noted that the veto authority he enjoys is different from that of other states, which underscores the need for Congress to pass something. “My veto is strong, and it will not be overridden, but there are other states that should consider federal action,” Evers said. “I’m disappointed that there hasn’t been, but I’m not sure it’s going to happen.”

For Democrats, the importance of electing and keeping Democratic governors in some of the priority states this cycle is clear. They will be among the most crucial stopgaps against Republicans’ likely push to tilt voting rules in their favor in the 2024 presidential election, especially if Donald Trump is once again on the general election ballot. That election will almost certainly be decided by the electoral votes from Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, perhaps North Carolina, and maybe Florida (where Republicans have been winning for a while and are likely to continue that statewide streak). Those states are where Democrats need their party’s governors to hold the line against changes that target the core of American democracy.