The House January 6 committee has spent most of the last 18 months working behind the scenes to investigate last year’s attempted coup d’état. That will change when it holds its first public hearing on Thursday in prime time, hoping to refocus the nation’s attention on the Capitol Hill attack and the events that led up to it.

Members of the committee, apparently hoping to maximize the opportunity, say they will reveal new findings after months of depositions and subpoenas. “The committee will present previously unseen material documenting January 6th, receive witness testimony, preview additional hearings, and provide the American people a summary of its findings about the coordinated, multi-step effort to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election and prevent the transfer of power,” the panel said in a press advisory.

Thursday’s hearing also comes amid reports of disagreement behind closed doors over what the committee’s legislative proposals should look like. According to Axios, Maryland Representative Jamie Raskin, one of the committee’s most prominent Democrats, has pushed for those proposals to include a recommendation that the Electoral College be abolished. Wyoming Representative Liz Cheney, the Republican co-chair, is reportedly resisting that call by telling her colleagues that pursuing this outcome would only undermine the committee’s credibility.

This fight doesn’t need to happen, and the committee needn’t come out and endorse the abolition of the Electoral College. The committee’s own existence is a testament to why the Electoral College should be scrapped: The fact that it exists and that the events that led up to the January 6, 2021, attack on the Capitol even happened, is solely the responsbility of our anti-democratic election mechanism. Without conceding the overall point, it might be more practical and productive for Democrats to focus their efforts on legislation that Congress could actually try to pass—such as a reform of the Electoral Count Act, to which members of both parties have signaled that they are amenable.

Yes: The Electoral College absolutely should be abolished, and Americans should get to choose the president in every election instead of just occasionally. But an endorsement of that goal by the House January 6 committee will not bring it much closer to fruition. It’s telling that Democrats, who currently control the House and Senate, have made no great effort over the past 18 months to push through a constitutional amendment that would abolish the Electoral College. This isn’t because they don’t want to do it, of course. It’s because the arithmetic isn’t on their side. Nothing the January 6 commission can do will change that anytime soon.

A constitutional amendment generally must be approved by two-thirds of Congress and three-fourths of the states. (There are other, even more unfeasible methods of achieving one, but it’s not worth contemplating them here.) Democrats fought hard to get a simple majority in both chambers to pass their flagship voting rights bills, and they still fell short. There is no chance that an even greater reform to the American electoral system—one that has effectively handed the presidency to the GOP twice in the last two decades—will receive the support of the 69 House Republicans and 17 Senate Republicans necessary for it to be sent to the states. Nor would 14 Republican-controlled state legislatures be likely to ratify it.

What can Congress actually do? The most immediate legislative goal should be the aforementioned revision to the Electoral Count Act of 1887. Federal lawmakers first considered a version of the ECA after the Electoral College deadlocked during the 1876 presidential election, which led to a constitutional crisis that only ended after Republicans and Democrats struck a backroom bargain to allow Rutherford B. Hayes, the GOP candidate, to take office. Near-crises in 1880 and 1884 led lawmakers to consider a more comprehensive solution to resolving disputes over a state’s chosen slate of electors.

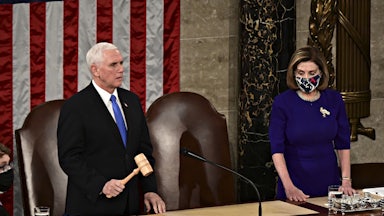

For more than a century afterward, however, the ECA was a historical footnote in the outcome of presidential elections. It was not seriously discussed again until the 2000 presidential election came down to a few votes in Florida. The 2020 election brought a renewed focus to the act when Trump and his allies sought to use the Electoral College and its various mechanisms to overturn the result itself. They pressured state lawmakers to decertify the election results and appoint new Trump-friendly electors, backed efforts to create alternative slates of electors without government approval, and tried to convince then–Vice President Mike Pence to unilaterally throw out the results during the joint session on January 6, 2021.

No law can prevent all coups in all forms. But the ECA’s weaknesses make it unusually dangerous for our democratic processes. Legal experts say that the law is unusually poorly written, even by congressional standards, and its vagueness makes it ripe for misinterpretation and manipulation. Clarifying the responsibilities of the joint session members and the vice president during the transition would help forestall similar crises in the future. It is notable that even some Republicans, such as Mitch McConnell, have expressed support for the possibility of ECA reform. Perhaps he is cognizant that the pro-Trump interpretation from 2020, where Pence could have unilaterally reelected himself and his running mate for four more years, won’t cut in the GOP’s favor when Kamala Harris presides over the next joint session in two years.

Axios’s report on the Raskin-Cheney debate also noted that other members have put forward their own potential legislative proposals. Florida Representative Stephanie Murphy, a Democrat, has reportedly drawn up a proposal to expand the federal laws that criminalize seditious conspiracy and other related crimes. Depending on how it is drafted, such a law could close a potential gap for these offenses that allows individual perpetrators to be punished but not those who orchestrate their actions. Cheney is also reportedly calling for the creation of a “supreme dereliction of duty” offense, likely in response to Trump’s refusal to quell the attack on the Capitol while it was underway.

Another law worth reviewing would be the Insurrection Act of 1807, which governs when the president can deploy U.S. troops to suppress rebellions and insurrections. The New York Times reported in April that the committee members were considering changes to the law in light of the events of January 6, when the president himself was a contributing factor in the civil unrest instead of an opponent of it. When Trump threw himself a military-themed parade in 2019, I proposed that Congress should ban the president from deploying the armed forces inside Washington without congressional approval. At the same time, lawmakers should also consider giving the mayor of the District of Columbia more control over the D.C. National Guard instead of routing that authority through the White House.

The January 6 committee’s most important function is truth-telling: To that end, it has gathered testimony and collected evidence with the aim of holding the former president and his allies accountable for their actions. Using the committee to propose abolishing the Electoral College is, in a way, a violation of that mission: There is no path for such a reform at hand, and suggesting that there is one only raises false hopes. It’s better to focus on legislative solutions that are substantive, that track with the committee’s duties, and stand a chance of passing, rather than aiming at more remote targets—however worthy they may be. A public hearing on prime-time TV won’t prevent Trump or future presidents from trying to overthrow the republic. But measures to counteract what we learned from January 6 stand a far better chance.