Halfway through Edith Wharton’s 1913 novel The Custom of the Country, Ralph Marvell confronts his father-in-law. “Where’s Undine?” he demands, by now suspicious that his wife has not yet arrived in New York from abroad. “If the train’s on time I presume she’s somewhere between Chicago and Omaha round about now,” replies Mr. Spragg. The locomotive, the symbolically named Twentieth Century, he adds, is “generally considered the best route to Dakota.” With this last word, the die is cast. “Oh, God,” Ralph cries out.

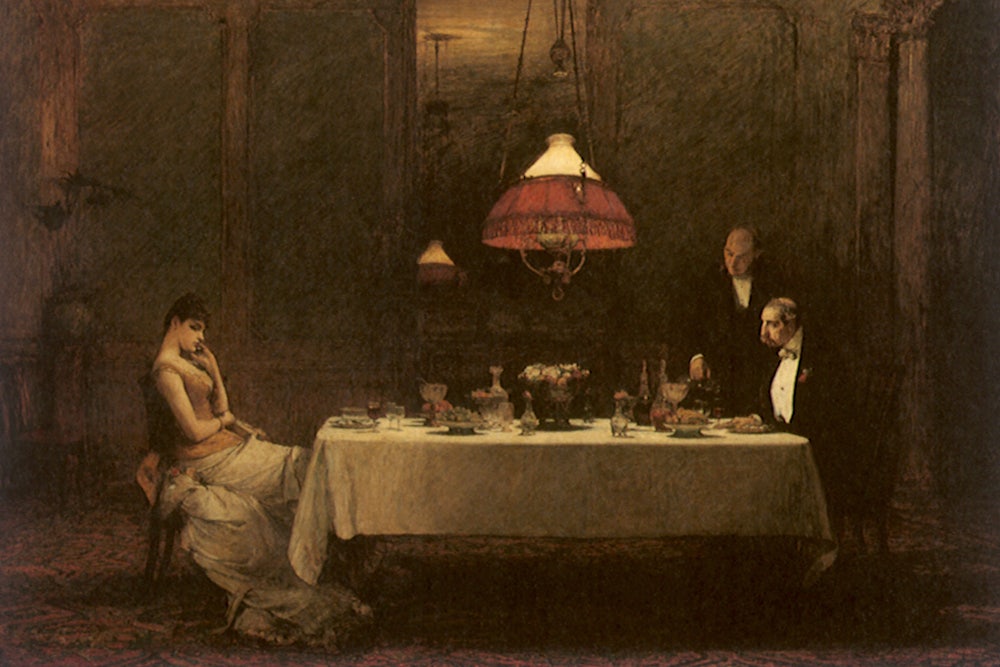

The new book The Divorce Colony by journalist April White gives readers of Wharton greater context for Ralph’s Dakota-induced despair. By the turn of the century, White explains, the phrase “going to Sioux Falls” had become “a euphemism for divorce among eastern elites.” While the moneyed set of Gilded Age New York City generally wanted for nothing, one thing that was out of its reach was reasonable divorce laws. In 1900, the only just cause for divorce in the state of New York was adultery, a tricky thing to prove even if true. So desperate was the situation that there even emerged “a cottage industry of actresses,” remarks White, “willing to play the role of the other woman for couples who wanted a divorce on the grounds of adultery without actually committing it.”

While the glitzy, modern people of the new century waited for the laws of New York to meet the moment, those who could afford to flee the state did just that. Nearby Rhode Island, where you could end a marriage over “cruelty” or “abandonment,” was a popular destination for these “migratory divorces,” but the state required one year’s residency before filing. For those with a secret fiancé waiting in the wings, such a delay was too much to bear. For the ardent and affluent, the frontier states beckoned with looser laws and new railway stations. The West was now to supply a new set of white Americans—more countess than cowboy—with its mythos of freedom. South Dakota was especially attractive as it only required plaintiffs live in the state for 90 days. A relatively short stay, it nonetheless meant that only the rich—who could afford to maintain a second residency for the duration of a trial—made up this new “divorce colony.”

White’s history of the Sioux Falls divorce colony is narrated energetically; she draws extensively on press reports from the time, giving the book the gossipy feel and lurid spin characteristic of Gilded Age media. Reading this, you get the sense that Americans used to have more fun with the English language; she quotes one divorce proponent from the time as saying: “To be deprived of a divorce is like being shut up in a prison because someone attempted to kill you.” Yet White presents these women as revolutionaries only by default; their private desires and personal bank accounts thrust them into national debates about divorce and the public interest. They faced some predictable antagonists: moralizing clergymen and men who did not want to pay alimony. But they also met opposition from the women’s movement, which was reluctant to embrace divorce as a feminist cause, fearing it could distract from the fight for the vote.

White focuses on four absurdly rich women whose marriages broke down in fittingly extravagant fashion, from the Astor who met her lover while staying at the Château de Fontenay at the invitation of the Comtesse de Montsaulnin (whatever that means) to a woman whose husband poisoned her paramour with spiked sniffing salts procured from the Carlsbad mineral springs. Money is the primary subject of The Divorce Colony; gold-backed dollar bills practically fall out of the pages. In foregrounding excess, White is not being sensationalist but rather intellectually honest, because at its heart, this is a story about rent, and who could afford to pay it for 90 days in Sioux Falls. If The Divorce Colony is wealth porn, it is wealth porn on a mission. In detailing what money makes possible, White gestures at what the lack of money forces women to endure.

The unhappily married women who traveled to Sioux Falls did so in style. From Grand Central Station, they set off by train first for Chicago aboard the luxurious North Shore Limited, preferably in the Wagner Palace Car: “a serene mahogany and brocade escape from the overflowing second-class accommodations and dismal third-class option.” The North Shore Limited discreetly advertised itself, writes White, “to unaccompanied woman travelers.” From Chicago, one had to transfer aboard another train, the Illinois Central, to head further west, and it was here that “a woman alone raised eyebrows,” especially if she was traveling with 34 pieces of luggage—like one of White’s subjects who was eager to part with her husband but apparently little else.

The divorce colony’s home base, as it were, was a luxury hotel in Sioux Falls called the Cataract House. Both the Cataract and the shops that sprang up around it served as an amusement park for the rich and bored. It “boasted sumptuously appointed parlors, elaborate dinner menus overflowing with fresh seafood and fruits year-round, and a constant swirl of social events,” writes White. The Cataract was also crawling with spies: society reporters dispatched from New York City and private investigators hired by the estranged spouses. The colony was not exclusively female, though the resident husbands never attracted much press interest. “A man who expected his freedom was not as outlandish as a woman who demanded hers,” White comments. The ultimate scoop, for journalist or detective, was a secret lover traveling in tow, a “private secretary” in an adjoining room, just waiting for the ink on the Dakota divorce decree to dry.

Such were the juicy headlines surrounding the arrival of Maggie de Stuers, the niece of William Astor who was divorcing her husband, a titled but moneyless Dutch aristocrat. On July 14, 1891, news that de Stuers was staying in Sioux Falls made the front page of the tabloid The New York World; The Boston Globe and The Chicago Herald also covered the story that the Cataract House had a new occupant, and an Astor at that. De Stuers was charging the baron with extreme cruelty. To the judge, she recounted his controlling nature: “My husband objected to my reading anything but history. One day I was reading a harmless English novel when he entered the room, snatched the book from me, and went out, slamming the door.” Her husband’s lawyers countered that she was having an affair with the man in Sioux Falls posing as her secretary, William Elliott Zborowski, better known in New York Society, writes White, as the “hero of the polo fields of Newport and the hunting grounds of Melton Mowbray.”

Blanche Molineaux had a more dramatic reason for seeking a divorce. She “believed her husband was a murderer.” Roland B. Molineaux was the son of a Civil War general who had become successful in business. Blanche, who came from lesser means, loved his pocketbook but found him lacking below the belt. She complained he possessed none of the “brute masculine force” she longed for. That was supplied to her by a friend of Roland’s from the Knickerbocker, who one day found a suspicious package of curing salts on his doorstep. Roland was eventually charged with the man’s death, induced by said salts, but the family appealed, and his execution was halted. “Roland was free; Blanche was trapped,” as White summarizes it. Blanche set off for Sioux Falls the day after her husband was released from Sing Sing.

Of the two other stories collected here, one involves the daughter-in-law of a Republican candidate for president (James G. Blaine of Maine) who wanted out from the political family. They tormented her, seeing her as little more than “a schemer who was not only Catholic but also an aspiring actress and a Democrat,” as White puts it. The other, the divorce of Flora Bigelow Dodge—an American aristocrat whose playmates included the German royal family and who took in horse shows with the Whitneys—is relatively straightforward. She married young, before she knew who she was, and now wanted something else. A mundane realization, but one that it required exceptional wealth to act on.

Indeed, one of the major findings from the census for 1887 to 1906 was that even as divorce rates tripled, compared to the previous decade, they did not rise as dramatically in the Southern states. Analyzing the numbers (which disproportionately counted white communities), one expert surmised that the reason white women in the South were less likely to seek divorce was because they had fewer economic opportunities than their counterparts above the Mason-Dixon line. Remarking on the dramatic uptick of divorces in the country, led for the most part by women (two out of three cases were initiated by wives), White remarks: “Nothing but a lack of money, it seemed, could thwart those determined to end their marriages.”

Lack of money, of course, is a common problem, one often exacerbated by gender. In some ways, this is why activists for women’s rights were split on the question of divorce and laws like the ones in South Dakota that made it easier to dissolve a marriage. Some feared fewer barriers to divorce would make it easier for men to leave their wives, which in many cases would impoverish the latter (not everyone could be like Dodge, who went on to marry a relative of Winston Churchill). Perhaps because of the sums of money often needed to initiate a divorce, there was at times a tendency to regard the matter as frivolous altogether (first-world problems, avant la lettre) or to paint the women of the Sioux Falls divorce colony as little more than greedy schemers. Wharton’s characterization of Undine, who uses divorce to continually marry up and replenish her coffers, is a prime example of the derision and skepticism that divorcees (like Wharton herself) often encountered.

Some women’s rights activists thus steered clear of the matter, worrying that such a divisive issue would fracture the all too important suffrage movement. However, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, the most influential suffragist of her time, disagreed. A close friend of hers had married a man who abused her. “I impulsively urged her to fly from such a monster and villain,” Stanton declared, “as she would before the hot breath of a ferocious beast of the wilderness.”

Since the days of the Cataract House, securing a divorce has become far easier by the letter of the law, with no-fault divorce available in all 50 states as of 2010 (New York was the final holdout). Yet some of what analysts surmised from the census data of 1906 remains true today. Divorce continues to be financially devastating for women; women are twice as likely as men to fall into poverty following a separation, and female victims of domestic violence regularly cite lack of economic dependence as a reason why they stay with their abusers. For all the glitz and glamor of the Sioux Falls colony, the greatest luxury these women possessed was the means to purchase a train ticket and their own lodging, which for some people—then and now—might as well be the Russian caviar and Moët & Chandon that Blanche Molineaux dined on when she first met her murdering husband. These wild stories of marital escape are a reminder, bright and sparkling for those who need it, that when endings are out of reach, so too are new beginnings.