Last November, Donald Trump visited Tampa for the rare event that lined someone else’s pocket rather than his own: headlining the “Countdown to the Majority Dinner,” the annual fundraiser for the National Republican Congressional Committee, which oversees the GOP’s efforts to retake the House in the 2022 midterms. “If we do our jobs and stick together, one year from today we are going to be watching a massive red wave sweep across our entire country,” the former president promised. But in typical fashion, he couldn’t help himself from attacking anyone in the party who dared stray from full fealty. “I say it with a heavy heart, no thank-you goes to those in the House and Senate who voted for the Democrats’ non-infrastructure bill,” he said.

Trump—who has spent the past year campaigning against incumbent Republicans who rebuked him following the insurrection on January 6, 2021—should pose a conundrum for Representative Tom Emmer, the NRCC’s leader. But, previewing a similar event in Texas this May, Emmer wasn’t subtle about the game during an interview with Fox News. Trump “has an amazing ability to help us raise money,” he said. After all, that Tampa fundraiser had netted the NRCC roughly $17 million.

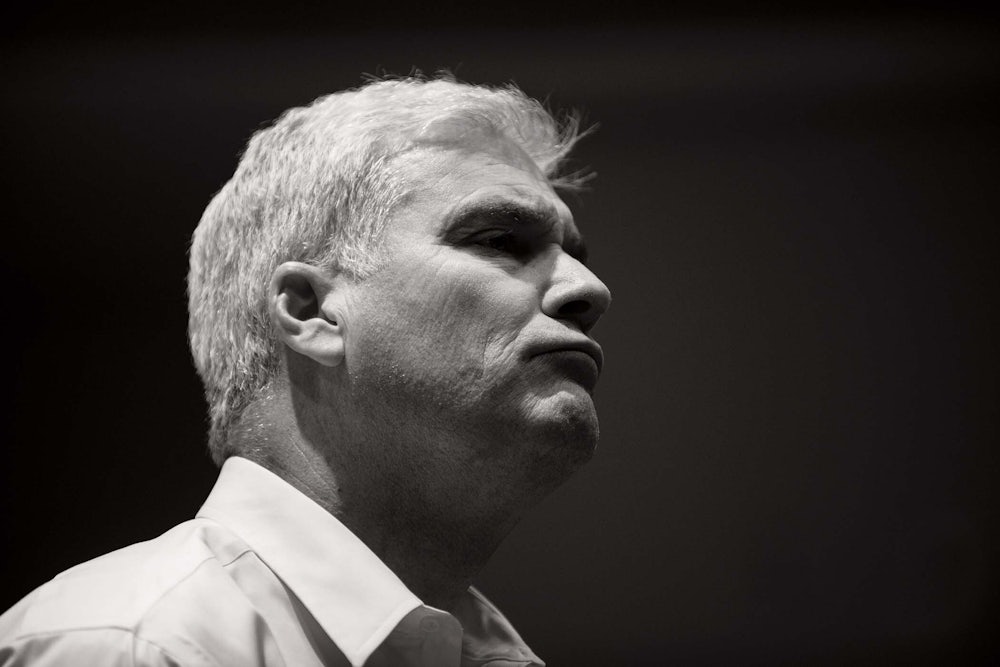

2022 will likely be a year of triumph for Emmer, the fourth-ranking Republican in the House. Under the watch of the four-term representative from Minnesota, the NRCC is targeting 75 seats; gaining more than 36 seats would give the GOP its largest House majority in nearly a century, but a net gain of just five would give the party control of the speakership. Along the way, Emmer has had to walk a difficult path of courting candidates who won’t alienate moderates (he often trumpets the increased number of recruits who are women or people of color) while not offending those clinging to the Big Lie. As a result, while Emmer may be successful—perhaps even winning himself a leadership post atop a House majority—he’ll have gotten there on the backs of insurrectionists and conspiracy theorists.

It’s a roundabout return for Emmer, who got his start in Minnesota as a tea partier before that was even a term. He “embodied a lot of the positive attributes of Trump before Trump was cool,” said Marty Seifert, the former Republican minority leader when Emmer was in the state legislature. “Outspoken, tell it like it is. Some people may not like you because of what you say, but I’m going to say it anyway.” Emmer inherited Michele Bachmann’s old congressional seat in 2014 with predictions that he’d replicate her style; but he came to Washington and quietly kept his head down, focusing on the policy and fundraising tactics that allow one to stealthily move up party leadership instead of being mocked on cable news.

The 61-year-old Emmer was raised in Edina, one of the tonier suburbs of Minneapolis (locals jokingly call residents “cake eaters”) and attended a Roman Catholic, all-boys military high school. While his hair has gone full silver, he still has the stocky build and jockish demeanor of the college hockey player he once was. He attended Boston College and the University of Alaska Fairbanks but returned to the Gopher State to get his juris doctor degree from William Mitchell College of Law. His family settled outside the Twin Cities in Independence, where, after buying the Old Shady Beach Resort Hotel, Emmer became outraged when the city billed him $30,000 for a new road and sewer system. “I got a little upset, so I started going to all the meetings at City Hall and complaining about it, only to be told that this is good for me, because my property values are going up,” he said in a video filmed by the state legislature that introduced him after he first won his seat. “Well, I wasn’t too pleased with that.” He ran and won a seat on the city council in 1995. After a couple of terms, as his family grew (he and his wife, Jacquie, now have seven kids), he settled in Delano (where he still lives), a town of about 6,000 at the far outskirts of the Twin Cities. He landed on the city council there, too, and in 2004, when the incumbent Republican in his district retired, Emmer won a seat in the Minnesota state House.

His tenure was defined by pushing far-right policy: proposals that Minnesota should chemically castrate sex offenders, impose strict voter ID laws, and outlaw abortion in all instances (as well as proposals that would also potentially outlaw certain forms of contraception and in vitro fertilization). He questioned evolution and was one of the loudest, most influential opponents of same-sex marriage. And despite two earlier DUI infractions, Emmer put forth bills to lessen penalties for drunk driving, which became fodder for opponents in later political campaigns.

Another of Emmer’s obsessions was pushing cockamamie ways that Minnesota could nullify federal laws. He was one of three co-authors of a 2010 proposal for a state constitutional amendment that would have required the governor and a two-thirds vote by legislators to approve a federal law before it could be enforced in Minnesota. “Citizens of Minnesota are sovereign individuals, subject to Minnesota law and immune from any federal laws that exceed the federal government’s enumerated constitutional powers,” Emmer’s would-be amendment read. (The idea went nowhere.)

“When he started off in the Minnesota House, he was a bit of a hothead,” said Larry Jacobs, the director of the Center for the Study of Politics and Governance at the University of Minnesota. During his first term, Emmer got in a shouting match with House Speaker Steve Sviggum, a fellow Republican, over a compromise government spending bill. “He gets very irritated and comes walking down the aisles with his fists in the air,” Sviggum recalled to me. When Sviggum walked forward with his own fists raised, cooler heads prevailed and separated the two. “He was probably an enforcer on the ice rink.… I’m not sure he was a scorer,” Sviggum said (hockey tends to come up when asking people about Emmer), “but I think he made people respect the scorers on the ice rink.” In a moment of Minnesota nice, Emmer brought Sviggum an apple pie baked by his wife the next morning, and the two hugged it out.

Emmer recognized the importance of building relationships and ran for the caucus’s top job after just two years in the House. When he came in second, Seifert made Emmer his deputy minority leader. Emmer then ran for governor in the Tea Party banner year of 2010, securing support from the likes of Sarah Palin. When Emmer secured the GOP nomination, it “was a confirmation that the Tea Party had overtaken the Republican Party,” Jacobs said.

“That was the mood of the nominating electorate at the time,” said Seifert, who was also Emmer’s main opponent in the GOP primary. “‘We want someone that’s a little bit edgier and someone that’s willing to push the envelope politically and rhetorically.’”

The Democratic gubernatorial nominee, Mark Dayton, didn’t seem imposing. An heir to the Dayton-Hudson department store fortune (later known as Target), Dayton had served a widely mocked single term in the U.S. Senate. Dayton had given himself an “F” grade when asked by Time for a self-assessment, and The New Republic dubbed his 2010 campaign “EEYORE FOR GOVERNOR.” Even his old family company donated $150,000 to a pro-Emmer PAC, which made national news as one of the first major corporate donations after Citizens United. (Target eventually publicly apologized, following outcry that the donation clashed with its image as a pro-LGBTQ employer.)

Yet Emmer’s campaign was even more inept. He advocated reducing the state’s minimum wage for tipped employees, claiming, “With the tips that they get to take home, they [sic] are some people earning over $100,000 a year”—and he tried to answer the backlash with a bizarre stunt of waiting tables at Ol’ Mexico Restaurante. He lost to Dayton by less than 1 percent—disappointing given that Republicans boasted a 25-seat gain in the state House and flipped the chamber. To top it off, Emmer staged a prolonged recount, and the legal challenge put his party $700,000 in debt before he conceded.

After his loss, Emmer retreated to the comforting confines of right-wing talk radio, playing shock jock during the Twin Cities morning commute show Davis & Emmer. His co-host, Bob Davis, was the punchier of the two, saying after the school shooting in Sandy Hook, Connecticut: “I’m sorry that you suffered a tragedy, but you know what? Deal with it, and don’t force me to lose my liberty, which is a greater tragedy than your loss. ” Emmer chimed in: “Well, they’re being used…. It’s probably one of the worst, ah, political stunts you could do is to use the victims of the tragedy.”

But he had never given up on electoral politics, and when Michele Bachmann decided not to run for reelection in 2014, Emmer won the race to replace her in the 6th District. “My impression, having talked with him afterwards,” Jacobs said of Emmer’s shift after the 2010 campaign, “is that it was a learning experience.… when he was in the Minnesota legislature, he was really focused on the base of the party—and he’s still obviously very sensitive to that. But he also appreciates how people [who] might disagree with him might perceive him.” (Emmer’s office and the NRCC did not respond to requests for comment.)

“When [he was] first elected to the Minnesota House, compromise was probably not part of his M.O.,” Sviggum added. “I think today there’s much more awareness of cooperation and compromise, while still having extremely conservative values.”

Emmer moved to Washington, no longer the bumbling candidate once featured on The Colbert Report for a campaign ad that was essentially a commercial for his contractor. Only a few months into his first term, Emmer gained a spot on the powerful Financial Services Committee, and today he is the top Republican on its Fintech Task Force. His press releases tend to focus on bipartisan bills around mental health rather than fringe conservative ideas. He even teamed up with a fellow Minnesotan, former Representative Keith Ellison, a Democrat, to form the Congressional Somalia Caucus. “He prides himself on relationships with Democrats in the delegation,” Jacobs said, “in a way that probably doesn’t help him. His district is rock-solid conservative Republican, and I don’t think he gets any votes for being a nice guy.” He didn’t join the rabble-rousing Freedom Caucus, and voted for John Boehner to remain as House speaker, earning the ire of Tea Party groups back in Minnesota. The TV cameras and negative headlines in the liberal press drifted away from Emmer, lured by louder proponents of hate.

Emmer didn’t immediately take to Trump’s presidential campaign in 2015, nor did he embrace the Never Trump ethos. But by the time Trump had secured the nomination the following summer, Emmer was announcing Minnesota’s delegate totals from the floor of the Republican National Convention in Cleveland and spending time in the Trump family box, as the only member of Minnesota’s House delegation to attend the RNC that year.

Following Trump’s election, Emmer rose in the NRCC ranks, becoming chair in late 2018, after Republicans lost their majority in the House. At the time, chairing the NRCC looked like a thankless task, as Trump was expected to further depress the GOP’s margins atop the ticket in 2020. But controlling the money begets relationships and influence, and just as he had in the state House, Emmer seemed eager to move to leadership in the House. And in a surprise, while Trump lost nationally by seven million votes, the House GOP netted 12 seats under Emmer’s first term.

Emmer spent December 2020 humoring Trump’s Big Lie conspiracies, joining 105 fellow House Republicans who signed an amicus brief asking the Supreme Court to overturn the election. Even after the Electoral College certified Joe Biden, Emmer refused to call him the president-elect. In the days ahead of January 6, Emmer wouldn’t answer questions from the Minneapolis Star Tribune about whether he’d vote to certify Biden’s victory. But in the end, Emmer was part of the small group of House Republicans who did. “It’s something that really mattered to him, and he understood that it could hurt his climb,” Jacobs said of that vote, noting that some die-hard Trumpists might view it as disqualifying if Emmer chooses to vie for a higher role in leadership in 2023. “This is not just expediency with this guy.” Shortly after the attack, Emmer would call the violence on January 6 “reprehensible”—but condemned Democrats for seeking to impeach Trump for inciting the coup attempt.

Within a month, Emmer was previewing the NRCC’s plans for 2022: ignore the insurrection as much as possible. But it, and the Big Lie, are impossible to ignore. Indeed, a key characteristic of many GOP primaries this year has been the propagation of the Big Lie. As of mid-June, according to a New York Times analysis, “At least 72 members of Congress who voted to overturn the 2020 election have advanced to the general election.” And Emmer is in charge of making sure they get reelected—as well as supporting newcomers like Scott Baugh in California and Jen Kiggans in Virginia, who have both refused to acknowledge that Joe Biden won the 2020 election. Then there’s Derrick Van Orden in Wisconsin, who was actually at the “Stop the Steal” rally in D.C. on January 6, and while he claims he didn’t enter the building during the insurrection, there are photos online of him just on the outskirts in a restricted zone of Capitol grounds during the attempted coup.

While Emmer has tried to keep up his jovial image, his old stripes shine through. He recently voted for a bill to codify that the federal government will recognize same-sex marriages, but as recently as late 2019, when asked of his old opposition, he said, “My views have not changed for me personally.” In each session since joining Congress, he has co-sponsored the Life at Conception Act, which declares life begins at the “moment of fertilization.” After the Supreme Court ruled in Dobbs, Emmer, while speaking at a GOP event whose audio was leaked, called House Democrats’ efforts to recodify Roe v. Wade “the Chinese genocide bill,” because “these guys think abortion should not only be available on demand, but it should be available right up to the day a child is born, and the day after in some cases.” (Fact-check: false.)

Emmer’s already using his party-climbing machinations to campaign for a better job title should the GOP retake the House. In August, Politico reported that Emmer has told colleagues he plans to run for majority whip, the third-ranking position in the House. In an earlier Politico piece this year speculating about his future, the publication noted his appeal both to the hard-right and the few lingering establishment Republicans and quoted one anonymous Republican: “We’re going to want to reward him, if there’s something that he wants that he doesn’t have.” Given the unsteady ground of likely House Speaker Kevin McCarthy, it might not be long before an even higher spot opens up.