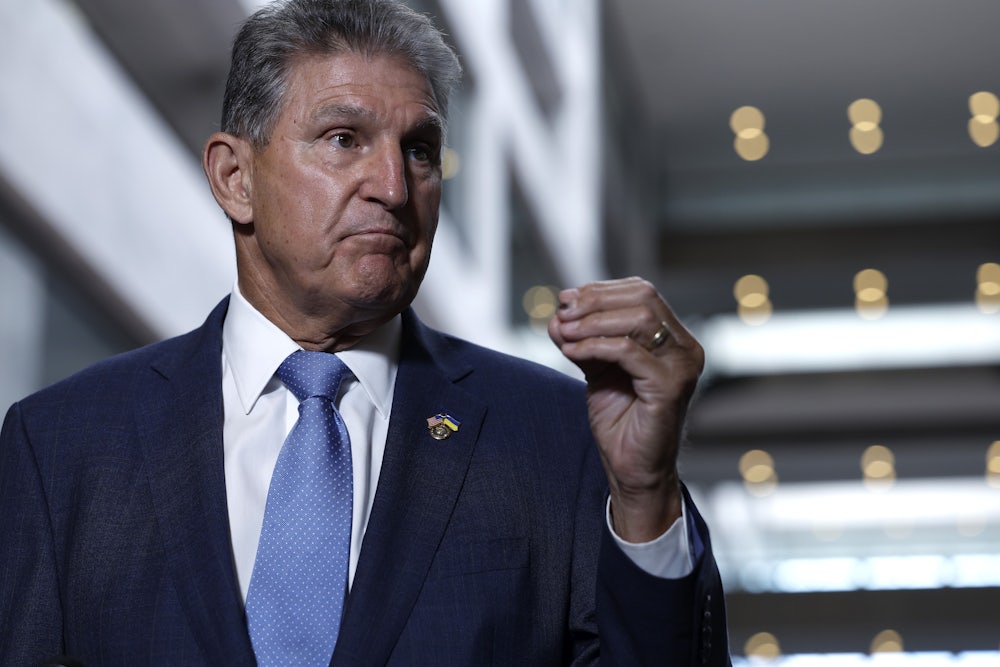

Perhaps the most shocking element in the surprise bill announced last week by Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and Senator Joe Manchin is its inclusion of climate provisions. Manchin, the conservative Democrat from West Virginia, had indicated that he would lend his support to a slew of measures, such as lowering prescription drug prices and cutting the federal deficit in a bill passed through the reconciliation process, without any Republican votes but with the support of all 50 Senate Democrats. But Manchin had told Democratic leadership only weeks before that he could not support any new spending on climate-related provisions with rising inflation, seemingly stymying President Joe Biden’s announced goal of cutting greenhouse gas emissions by 50 percent below 2005 levels by 2030.

So when Manchin and Schumer unveiled a $740 billion proposal that included not only health care and tax provisions but measures to boost renewable energy production and encourage consumers to buy electric vehicles and energy-efficient home appliances, many climate activists were thrilled. Democrats are widely expected to lose control of the House of Representatives after the November elections, meaning that they only have the next few months to pass legislation containing their priorities without any Republican support.

“It really was devastating to think that there would be no federal climate action for yet another decade,” Leah Stokes, a professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara and an expert on energy and climate policy, told me. “And so failure is not an option. With this bill, we will be on track to meet President Biden’s goals and cut pollution by half by 2030. We’ll get 80 percent of the way to that goal. And without it, we’re really sunk.”

Senate Democrats claim that the bill would reduce carbon emissions by 40 percent below 2005 levels by 2030, which is still lower than Biden’s goal. Humans have already heated the planet by 1.1 degrees Celsius (two degrees Fahrenheit) since the nineteenth century, according to a United Nations report published last year, and scientists have warned that the whole world would have to cut emissions by half by 2030 to limit global warming to just 1.5 percent degrees Celsius—still a dramatic increase that will have worldwide repercussions.

The climate portions of the bill largely employ the carrot rather than the stick, encouraging the transition to renewable energy for private companies and individual consumers. This includes billions in tax incentives to boost production of wind, solar, and battery power along with other clean energy. Producers may receive credits both for generating renewable power and manufacturing specific parts for projects such as solar panels or wind turbines. An analysis of an earlier version of these proposed credits by economists at the University of Chicago and the Rhodium Group found that they would create a $1.5 trillion economic surplus and eliminate more than five billion tons of carbon pollution through 2050.

These provisions will also be a boost for clean energy producers in general, as a recent report by the American Clean Power Association found that clean energy deployment decreased significantly in the second quarter of this year. “The entire clean energy industry just breathed an enormous sigh of relief. This is an 11th hour reprieve for climate action and clean energy jobs, and America’s biggest legislative moment for climate and energy policy,” Heather Zichal, the association’s CEO, said in a statement last week. (Zichal previously advised Biden’s campaign on climate after serving as a top aide for President Barack Obama’s Domestic Policy Council; after her time with the Obama White House, she became a board member of Cheniere Energy, which, as my colleague Kate Aronoff noted, was “the first company to export natural gas from U.S. shores after the Obama administration loosened restrictions in 2013.”) The tax credits for solar and wind production would also outlast a Democratic Congress and administration: Instead of a one- to two-year cycle of credits requiring frequent extensions, these subsidies would last up to 10 years.

The Inflation Reduction Act will also create a Methane Emissions Reduction Program, which will reward companies that cut their methane emissions and punish those that do not. By 2026, companies in violation of federal limits could pay $1,500 per ton of methane that escapes into the atmosphere. Methane, a powerful greenhouse gas, is roughly 80 times more effective at trapping heat than carbon dioxide, meaning that reducing such leaks is vital to prevent the planet from warming further. The bill would also invest $27 billion to create a “clean energy and sustainability accelerator,” commonly called a green bank, which would use public and private funds to invest in clean energy and infrastructure.

It would offer a $7,500 tax credit to buyers under a certain income level to purchase new electric vehicles, and a $4,000 credit for used ones. There would be $9 billion dedicated to consumer rebates and tax credits to install heat pumps, solar panels, and more to make homes more energy efficient. A recent analysis by Rewiring America, a climate policy organization, found that a household that retrofits and installs energy-efficient appliances could save $1,800 annually on energy bills, albeit after the not insignificant purchases of an E.V., a heat pump, and solar panels. There are also elements in the bill relating to environmental justice, such as block grants to aid communities disproportionately affected by the harmful effects of climate change and pollution.

“This is going to put billions of dollars into communities that will literally help save children’s lives,” Senator Cory Booker told me last week, praising the bill’s $60 billion dedicated to environmental justice; he noted that Black children are several times more likely to die from asthma complications than white children, a health disparity that stems in part from disproportionally living in areas with high pollution. “I’m rejoicing that this is literally going to save thousands of lives in vulnerable populations and deal with the real, immediate issues of climate change that people often overlook,” he said.

The bill is also more inclusive to rural communities, who are often left out of climate investments: It invests billions in “climate-smart agriculture practices” and provides tax credits and grants to produce biofuels. However, it does not include a new investment tax credit for long-distance power lines, which could help connect solar and wind energy sites to population centers; the credit had been included in an earlier version of the bill.

The bill has not been met with universal praise. Brett Hartl, the government affairs director at the Center for Biological Diversity, argued that whatever good would be accomplished by the tax incentives would be countered by the bill’s support for fossil fuel programs. “There’s obviously a lot of folks trying to paint the best, rosiest picture of this bill and promising all sorts of reductions and emissions, but I don’t think the math works. And I think they’re being extremely, overly optimistic about it,” he said.

The bill includes a 10-year window in which the government may only issue new offshore wind leases if an oil and gas lease has also been sold in the previous year. Hartl expressed skepticism that this plan could result in the 40 percent reduction in emissions that Democrats are claiming. He pointed to preliminary analysis from Rhodium Group showing that the Inflation Reduction Act could cut U.S. emissions 31 percent to 44 percent below 2005 levels by 2030, compared to 24 percent to 35 percent under current policy, an eight percentage point change that he argued was “definitely not enough to avert a climate catastrophe.” Energy Innovation, a nonpartisan energy and climate policy think tank, released a report on Monday finding that the legislation would cut greenhouse gas emissions by 37 to 41 percent below 2005 levels.

The provisions on fossil fuel were concessions to Manchin, who has previously called for more drilling on federal lands and emphasized the importance of energy independence. “I wasn’t budging from making sure we had a robust energy portfolio,” Manchin said in an interview with a West Virginia radio show on Thursday.

The bill would also mandate new lease sales for oil drilling in Alaska’s Cook Inlet and the Gulf of Mexico—the offshore oil and gas lease sale in the Gulf had been halted by a judge who determined an insufficient environmental review had been conducted. “It’s incredibly harmful to so many frontline communities, especially in the Gulf of Mexico, who have been poisoned for decades by fossil fuels. And we’re basically telling them, ‘You get to keep suffering and bearing the brunt, while we do good things elsewhere.’ So it’s a pretty bitter pill and a pretty rotten trade,” Hartl said.

But Stokes countered that the positives far outweighed the negatives. She noted that the requirement for lease sales included in the bill is at a lower benchmark than what has historically been permitted and moreover said that sales do not necessarily result in production. “I think it’s really important that we communicate the scale of the good stuff in the package,” Stokes said. “It’s easy to just say: ‘Oh, fossil fuel leasing. Bad.’ But these are not the same.”

As one professor at the University of Texas pointed out on Twitter, in the most recent offshore sale by the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, only 2.3 percent of acres in the sale were actually leased. The Natural Resources Defense Council further estimates that “the positive climate provisions could outweigh the negative by eight to ten times from a greenhouse gas emissions perspective.” The Energy Innovation report calculated that for every one ton of emissions caused by oil and gas leasing, at least 24 tons of emissions would be avoided by other provisions in the bill.

In his statement announcing the agreement, Manchin also said that he has secured a commitment from Biden and Democratic leaders in the House and Senate to advance a permitting reform bill, which could weaken the importance of environmental considerations when developers build a pipeline or other energy infrastructure. The Washington Post reported on Monday afternoon that Manchin and Democratic leadership had reached a separate deal aimed at expediting the approval process for energy projects, limiting environmental reviews for “major” projects to two years. This bill, which would need Republican support to pass, would also approve a pipeline transporting shale gas from West Virginia. Protect Our Water, Heritage, Rights, a conservationist organization based in West Virginia and Virginia, criticized the reported deal: In a statement, development and programs coordinator Grace Tuttle said that “we refuse to be sacrificed for political gain or used as concessions to the fossil fuel industry in this so-called deal.”

“It makes the bill less effective than it would otherwise be,” said Michael Mann, distinguished professor of atmospheric science at Penn State and author of the book The New Climate War, in an email. But Mann also called the Inflation Reduction Act a “good start and probably the best we can get right now,” saying that Democratic voters needed to turn out in the midterms if they wanted to see more comprehensive climate change legislation passed. “The U.S. is the largest historical carbon polluter, and without leadership on our part it will be difficult to bring other critical countries, like China and India, to the table,” Mann wrote.

The inclination among many is to take the victory, while acknowledging that there is still work to be done. Stokes called on the Biden administration to continue to take executive action related to climate change and highlighted the work that states and cities can do to invest in clean energy.

“We need cities and states to act. They can do that extra 10 percent, they can fill in the gap,” Stokes said, referring to Biden’s goal of cutting emissions to 50 percent by 2030 if the new legislation reduces them by 40 percent. “They could not have filled in the gap without this legislation. Even if we had great leadership with the Biden administration, that gap would have been glaring, it would have not been doable.”

Meanwhile, Manchin has embarked on a sales pitch for the bill, highlighting its energy portions along with the provisions focused on reducing the deficit. “I think that time will tell, this is a balanced bill that gives us energy security our country desperately needs. Because it’s a pathway forward. It gives us [the] ability to take care of ourselves, to be an energy producer, and also be able to invest in technology for the energy future,” Manchin told reporters on Monday.