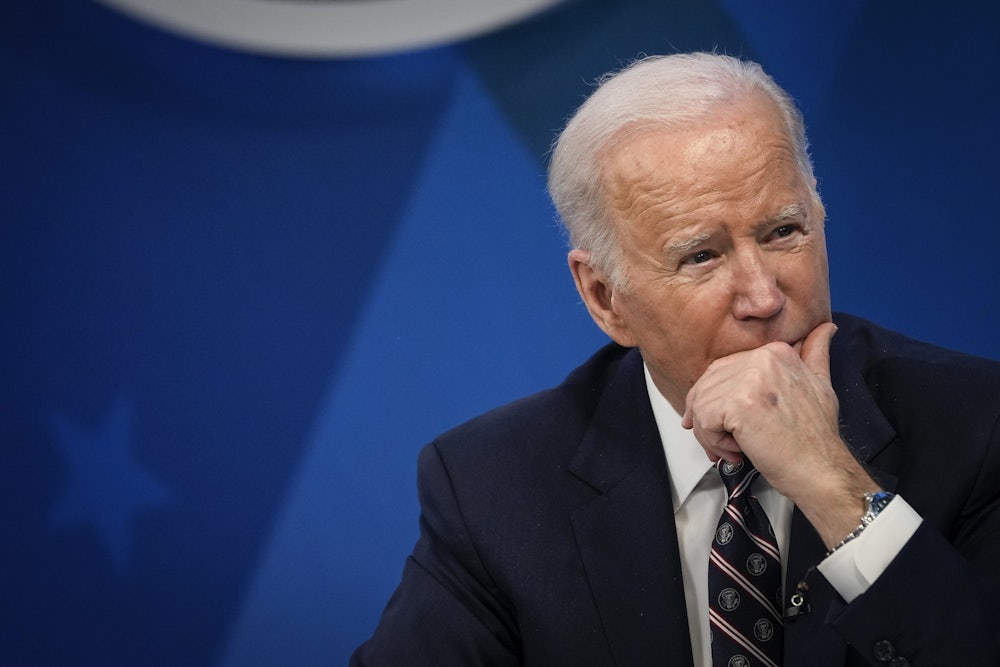

President Joe Biden has striven to be known as a “pro-labor president,” including in his statement self-attesting to that description on Monday, in which he called on Congress to reject the will of thousands of union workers. But in asking lawmakers to pass legislation to prevent a freight rail strike, Biden took door number two of a no-win scenario: Allow the strike to go forward, crippling the economy amid rising inflation during the holiday season, or hand a defeat to some of his allies in labor.

“I am calling on Congress to pass legislation immediately to adopt the Tentative Agreement between railroad workers and operators—without any modifications or delay—to avert a potentially crippling national rail shutdown,” Biden said on Monday evening. Speaker Nancy Pelosi swiftly released her own statement saying that the House would consider the legislation adopting the tentative agreement this week.

After meeting with Biden at the White House, Pelosi and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer reaffirmed their commitment to quickly addressing the issue. “Tomorrow morning we will have a bill on the floor,” Pelosi said. “I don’t like going against the ability of unions to strike, but weighing the equities, we must avoid a strike. Jobs will be lost. Even union jobs will be lost.” Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell agreed that “We’re going to need to pass a bill.”

Biden has avoided seeking congressional action on the issue for months, instead allowing for the freight rail industry and union members to negotiate a contract. But with a strike set to begin as early as December 9, Biden said in his statement that his secretaries of labor, transportation, and agriculture “believe that there is no path to resolve the dispute at the bargaining table” in time. The deadline for an agreement to be reached is December 8.

The tentative agreement between railroad companies and unions was reached in September after negotiations overseen by Labor Secretary Marty Walsh, temporarily averting a strike. That deal was rejected by four of the 12 railroad unions, representing most railroad workers, who are frustrated by the lack of paid sick days. The agreement offered all members a 24 percent pay increase by 2024, allowed unions to negotiate more regular schedules for workers, and capped health care premiums. But although it allowed members to call out an additional three days a year for routine doctor’s appointments, it only granted conductors and engineers an additional single paid day off, and did not meet their sick leave demands.

Asking Congress to address the issue puts pressure on lawmakers already facing a slew of issues in the lame duck session, including a mid-December deadline to fund the government. The legislation will also need to be bipartisan, particularly since it will need to meet a 60-vote threshold to advance in the Senate; some Democrats may also choose to vote against it due to their concerns about the absence of sick leave provisions. (However, some Republicans have indicated skepticism about such legislation, potentially complicating its path forward; McConnell acknowledged to reporters that there were “mixed views” on the issue in his conference.)

When asked if she would vote against a bill to prevent a strike, Senator Elizabeth Warren told me that “we’re not there yet.” “I’m hopeful that a deal will be worked out. The best way to get that deal worked out is to keep pushing the parties,” she said.

“It’s very important that we not shut down the economy because we can’t move goods. But the unions make a very fair point when they say that they should have access to sick days,” Warren told me. But she also criticized the railroad companies that “want to scoop in all the wealth for themselves,” a sentiment echoed by Senator Bernie Sanders.

“If you are a worker today in that industry, and you are diagnosed with Covid, you are penalized for being sick. You can’t be with your wife if she’s giving birth. We have got to fight to make sure that workers in the rail industry get the guaranteed paid sick leave that every American should have,” Sanders said. He indicated that he would force a vote on the topic. “So if your question is: Will I demand a vote to make sure that workers in the rail industry have … guaranteed paid sick leave? The answer is yes.”

Senator Kirsten Gillibrand also signaled that she would push to have a vote on the issue, telling reporters: “I’m hopeful we can guarantee them a week of sick days and I’m working with Senator Sanders and others to get that done.” Sanders later added that he would not support the legislation without an amendment on guaranteed paid sick leave attached. “I would object to just proceeding on the president’s proposal. The president made some progress, but I think we can and must do it,” he said. Given that lawmakers want this to be addressed quickly, it’s possible an agreement to limit debate time could include a promise to vote on such an amendment.

Sanders tweeted Tuesday evening that “it’s my intention to block consideration of the rail legislation until a roll call vote occurs on guaranteeing 7 paid sick days to rail workers.” This may be able to garner some support—Senator John Hickenlooper also said that “any bill should include the seven days of sick leave rail workers have asked for.” Sanders spoke for a few moments with GOP Senator Marco Rubio on the Senate floor Tuesday evening; Rubio tweeted earlier that day that “the railways & workers should go back & negotiate a deal that the workers, not just the union bosses, will accept.”

When asked to respond to Sanders’ demand, Schumer said: “We’re going to work it out and get it done.”

Senator Sherrod Brown, another Democrat who is staunchly pro-labor, told reporters on Tuesday that he supported Biden’s efforts. “It’s clear the rail companies are greedy in refusing this,” Brown said, but added that he was “concerned about what could happen to the economy” if there was a strike.

Several progressives in the House have already indicated that they will not support the legislation without sick leave provisions. “I can’t in good conscience vote for a bill that doesn’t give rail workers the paid leave they deserve,” Representative Jamaal Bowman tweeted on Tuesday.

Representative Steny Hoyer, the House majority leader, said that he believed it would need to be a bipartisan vote, although he added that he was “sympathetic to the issue of sick leave.” “Whether we pass this bill now or not, I think we need to focus on that issue,” Hoyer told reporters on Tuesday. “The labor unions make a very valid case.”

Recognizing the instinct among Democrats to perhaps push for additional provisions in the legislation, Biden warned in his Monday statement that it should be a clean bill. “Some in Congress want to modify the deal to either improve it for labor or for management. However well-intentioned, any changes would risk delay and a debilitating shutdown,” he said, noting that the tentative agreement had been reached between the industry and union leaders. Biden added that he would continue to work towards implementing paid leave, but “at this critical moment for our economy, in the holiday season, we cannot let our strongly held conviction for better outcomes for workers deny workers the benefits of the bargain they reached.”

In a sense, Democrats are presented with a trolley problem—no pun intended—weighing the desires of thousands of workers for a more equitable workplace against the functioning of the larger economy. (The votes by unions to accept or reject the agreement have generally been decided by narrow margins.) Biden argued in his statement that “a rail shutdown would devastate our economy,” with the result that “as many as 765,000 Americans—many union workers themselves—could be put out of work in the first two weeks alone.”

A recent analysis by the Anderson Economic Group found that a rail strike could cost the U.S. economy $1 billion in its first week—disrupting supply chains and potentially worsening inflation. It would interfere with the transportation of critical products like food for livestock, lumber, and chemicals which are necessary for water and wastewater treatment.

Meanwhile, some tech companies are already bracing for a strike, rerouting cargo shipments from railroads to trucks, CNBC reported. But according to a September letter from the American Trucking Association, a railroad strike “would require more than 460,000 additional long-haul trucks every day, which is not possible based on equipment availability and an existing shortage of 80,000 drivers.”

“Many businesses will see the impacts of a national rail strike well before December 9—through service disruptions and other impacts potentially as early as December 5,” a coalition of business groups led by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce said in a letter to congressional leaders on Monday. “The sooner this labor impasse ends, the better for our communities and our national economy.”

It might be difficult for Biden to find himself on the opposite side of his traditional equation: In 1992, he was one of six senators to vote against a bill to end another rail strike, saying federal intervention was “what the workers fear and the railroad companies are counting on.”

Now, three decades later, some union members feel as if Biden has let them down. “This action prevents us from reaching the end of our process, takes away the strength and ability that we have to force bargaining or force the railroads to … do the right thing,” Michael Baldwin, president of the Brotherhood of Railroad Signalmen, told CNN. “The railroads have the ability to fix this problem. If they would come to the table and do that, we could move forward without congressional action.”

Hugh Sawyer, the treasurer of the Rail Workers Union, a coalition of union activists who opposed the tentative agreement, was more forceful in his condemnation. “Joe Biden blew it. He had the opportunity to prove his labor-friendly pedigree to millions of workers by simply asking Congress for legislation to end the threat of a national strike on terms more favorable to workers,” Sawyer said in a statement. “Sadly, he could not bring himself to advocate for a lousy handful of sick days. The Democrats and Republicans are both pawns of big business and the corporations.”

This post is about a breaking news event and has been updated.