Four of the country’s biggest oil companies—Chevron, ConocoPhillips, Exxon, and Shell—reported record profits last year. Shell made $40 billion—double what it had the year prior. Payouts to shareholders across the industry increased by 76 percent over the previous year, stretching up to $200 billion. And the gifts keep on coming.

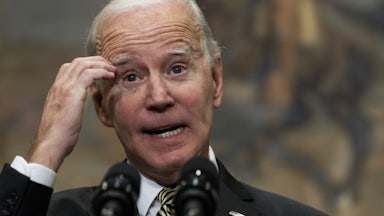

This week, the Biden administration moved toward approving an $8 billion ConocoPhillips project in the National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska, located in Alaska’s North Slope. The company’s Willow project is expected to produce some 600 million barrels over the next 30 years in one of the fastest-warming parts of the planet. Critics argue the project threatens already endangered Indigenous livelihoods there. The Bureau of Land Management, meanwhile, issued its Final Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement, recommending the company drill three wells instead of the five it initially proposed. The Department of Interior, which noted it still has “substantial concerns” about the project’s climate and environmental impacts, will have 30 days to decide its fate. “That decision may select a different alternative, including no action, or the deferral of additional drill pads beyond the single deferral described under the preferred alternative,” the department wrote in a press statement about the BLM recommendation.

ConocoPhillips, for its part, seems confident. Reporting profits that doubled to $18.7 billion in 2022, chairman and CEO Ryan Lance told analysts on Thursday that the company is “moving forward with our little project up in Alaska.” Seeming to take a jab at critics, including in the White House, Lance added that “this is what the administration has asked us for: U.S. production that’s low GHG emission production. This is exactly what the administration has asked us to do as an industry, and that’s what we are trying to do as a company.” Over the next 30 years, Willow is expected to produce carbon emissions equivalent to what a third of America’s coal-fired power plants produce in a year. ConocoPhillips also hopes for Willow to be an anchor for a larger expansion in the Western Arctic to develop three billion barrels of oil. If burned, those barrels would belch out emissions equivalent to what the entire U.S. transportation sector produces in a year.

Andy O’Brien, ConocoPhillips senior vice president of global operations, was optimistic about Willow’s prospects. “Now, given the Biden administration’s commitment to the Alaska congressional delegation, we can expect to receive that [decision] in the first week of March,” he said.

Despite Democrats’ much-vaunted climate victories in the past year, the Biden administration has been a lucrative time for the oil and gas industry. While Biden came into office pledging a hard line on new drilling projects, the administration’s oil and gas drilling approvals so far have outpaced the Trump administration’s. As the industry accumulates record profits, the White House plans to start refilling the Strategic Petroleum Reserve. Nor does the industry itself see the the climate spending in the Inflation Reduction Act as a threat. Speaking with analysts about their $55 billion profits last year, ExxonMobil’s corporate leadership contrasted windfall taxes in Europe with the approach taken in the United States.

Taking a hostile line toward the European approach, senior vice president and chief financial officer Kathy Mikells called European taxes on windfall energy profits “not legal” and “the opposite of what is needed.” She said that “what’s needed right now is more supply. And instead, what’s been put in place is a penalty on the broad energy sector.”

She had warmer words for the IRA: “I’d contrast that,” she said, “with what’s happened more recently in the United States with the Inflation Reduction Act, right? There you see policy that’s put out to incent industry, both to accelerate technology and accelerate investment that’s greatly needed, especially in areas where the industries in terms of lowering emissions are still pretty nascent, things like hydrogen and CCS.”

Former Shell CEO Ben van Beurden, who stepped down at the end of 2022 and whose company announced it will buy back $4 billion in shares over the coming months, has described decarbonization as a potential win-win to the oil industry so long as policies toward it reflect corporate priorities. Early last year, he talked about the need to “grow our cash flows while at the same time reducing our carbon footprint.” He suggested, as well, that the company’s outsize role in shaping climate policy allows it to profit from new revenue streams such policy might create, without threatening profits:

How do I work together with my customers, and maybe with regulators, depending on which jurisdiction we are working in, to grow that business? So at this point in time, it is a shift from, well, if the opportunity is there, we may actually take advantage from it, to, how do I make sure that this opportunity will come? I’m the one shaping it, and I’m actually the one building the customer loyalty and the solution space and the infrastructure very early on in the journey so that we have a lock-in of future profitability. That is what our strategy is all about when it comes to pursuing net-zero.

Referencing some far-off point when an energy transition might occur, he added later that “before the market will completely transition to a low-carbon market, it will just be adding low carbon demand onto existing demand.” For now, that’s what appears to be happening, given that politicians in the U.S. seem unwilling, despite their enthusiasm for renewables, to pass policies that actively wind down fossil fuel production.

Shell’s new CEO, Wael Sawan, stuck by the company line on this week’s earnings call. “By the way, by 2040, I’m still convinced you’re going to need oil and you’re going to need gas and you’re going to need a lot more renewables,” he said. “And so our strategy is one that’s saying, how do we play across these multiple energy forms but really focus on the opportunities that create the most value for us?”

The “all of the above” approach to climate policy the Biden administration has taken is serving the oil and gas industry well. The trouble is that a win-win for the oil and gas industry isn’t one for the planet.