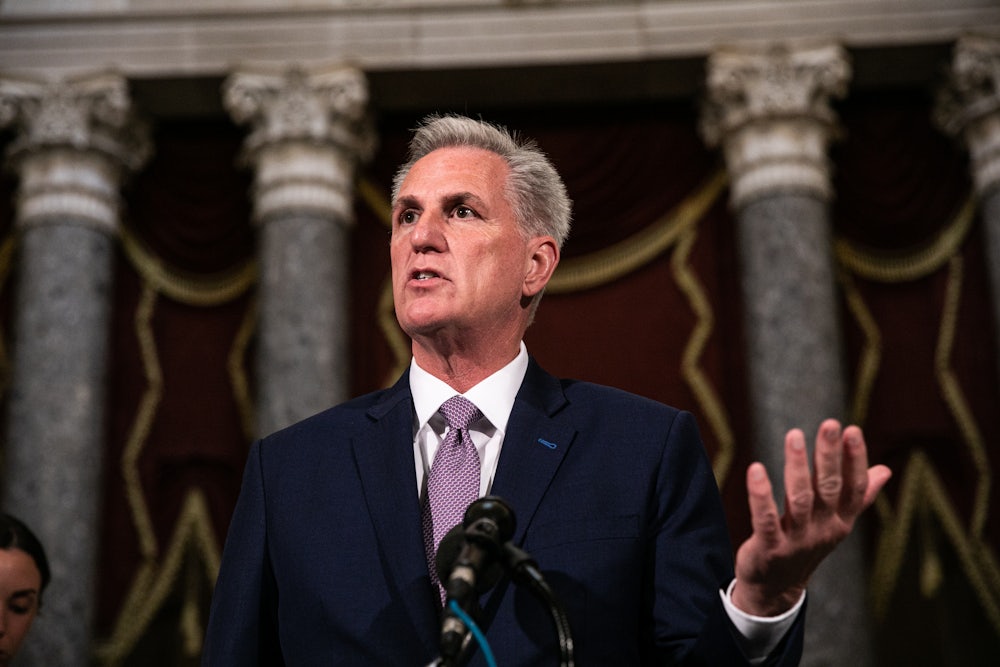

Republicans are hating on food stamps again. House Speaker Kevin McCarthy’s debt-ceiling bill expanded coverage of an existing work requirement to receive food stamps to include people aged 49 to 55, who were previously exempted. That wasn’t good enough for Representative Matt Gaetz of Florida, who has called nonworking food stamp recipients “couch potatoes.” So before the bill cleared the House on Wednesday, 217–215, it was amended to accelerate to October 2024 the deadline for quinquagenarian recipients to get jobs. (Gaetz voted against the bill anyway.)

The paradox of the food stamp program is that it was originally designed to benefit three Republican constituencies: farmers, grocers, and wholesalers. (Even today, one of the program’s biggest supporters is Walmart.) Yet food stamps have come under near-constant attack since 1976, when Ronald Reagan, then challenging Gerald Ford for the Republican nomination, disparaged a largely mythical African American “welfare queen” who “used 80 names, 30 addresses, 15 telephone numbers to collect food stamps, Social Security, veterans’ benefits for four nonexistent deceased veteran husbands, as well as welfare.”

Food stamps were first conceived as a subsidy to business during the Great Depression. President Franklin Roosevelt’s Agriculture Department had been purchasing surplus crops from farmers and distributing them to hungry families. Food wholesalers and retailers, including the supermarket chains that were just starting to appear (and that marketed themselves as heavy discounters) objected to being cut out of the deal. Food stamps were the resulting compromise. Instead of the government purchasing the surplus food, wholesalers did. The wholesalers sold the food to retailers, who in turn sold it to individuals able to make their purchases with government-issued stamps.

Today’s Republicans fulminate about nonworking couch potatoes who collect food stamps (never mind that most recipients work already; in households with children, 75 percent do unless they’re disabled or elderly). But back in 1939, being unemployed was the reason you went on food stamps; as with most New Deal social welfare programs, the idea was not to punish jobless people, but to help them. Christopher Bosso, a political scientist at Northeastern University and author of the forthcoming Why SNAP Works, told me that eligibility for the New Deal program often depended on the recipient’s being enrolled locally in a relief program: no welfare, no food stamps. (SNAP, or the Supplementary Nutrition Assistance Program, is what food stamps were renamed in 2008, in a half-hearted effort to reduce the stigma, which didn’t take.) The very first recipient, a machinist in Rochester, New York, named Ralston Thayer, was Gaetz’s worst nightmare: 35, able-bodied, and unemployed. “I never received surplus foods before,” Thayer told reporters, “but the procedure seems simple enough, and I certainly intend to take advantage of it.”

Food stamps disappeared as the economy recovered during World War II. In the 1950s, Senator George Aiken, a Vermont Republican, agitated for food stamps’ revival, but the Eisenhower administration wasn’t interested. These were prosperous years when, as Michael Harrington would observe in his 1962 book, The Other America, the poor became invisible, even to liberals. That began to change under President John F. Kennedy, partly because of Harrington’s book, and by 1964 food stamps had been legislated back into being. The Food Stamp Act’s preamble stated as its purpose, first, “to strengthen the agricultural economy”; second, “to help achieve a fuller and more effective use of food abundance”; and only third (oh, yeah), “to provide for improved levels of nutrition among low-income households.” Even so, Republican opposition (combined with resistance from Southern Democrats) nearly tanked the bill. Representative John McCormack of Massachusetts, the Democratic House speaker, finally secured support by tying it to aid for cotton and wheat farmers.

McCormack’s maneuver established a precedent. Since 1973, the food stamp program has survived largely because it’s been folded into the big farm bills passed every five years or so on which big agriculture relies. As the political scientist Matthew Gritter observes in his 2015 book, The Politics of Food Stamps and SNAP, the strategy “provided the program with an institutional place outside the contentious welfare program.” It wasn’t enough to spare the program Reagan’s scorn, but it was sufficient to win support from key farm-state Republicans like Kansas Senator Bob Dole, who in 1977 teamed up with Democratic Senator George McGovern to expand access to food stamps.

Reagan’s 1980 election prompted a series of cuts to the food stamps program. President Reagan told Congress in 1981 that a program originally intended “to ensure adequate nutrition for America’s needy families” had devolved into a “generalized income transfer program.” But in fact, about 90 percent of the families receiving food stamps were below the poverty line, with the average living on $3,900 a year (about $13,000 in current dollars). Among the “reforms” Reagan imposed were a ban on federal outreach to let poor people know food stamp benefits were available, a reduction in cost-of-living adjustments from twice yearly to annually, and the first in a series of escalating work requirements.

Reagan’s assault on food stamps, and on welfare benefits generally, abated in the mid-1980s because, Bosso said, “Republicans got their heads handed to them on being so cruel to the poor and hungry.” At that point, Republicans and Democrats struck an unspoken bargain: Democrats would be permitted to enlarge overall eligibility in the food stamp program so long as Republicans were permitted to tighten it in petty and politically charged ways.

Sometimes the Democratic hostage is something other than expanded food stamp eligibility. Today, the hostage is the debt ceiling. In 1996, it was President Bill Clinton’s welfare reform. When Clinton said he wanted to “end welfare as we know it,” he meant cash welfare, not food stamps. But one of the prices Republicans demanded was a variety of restrictions on food stamp eligibility, including the denial of benefits to legal immigrants who weren’t American citizens and a three-month limit on benefits to able-bodied recipients who didn’t work.

President George W. Bush broke this pattern by expanding food stamp eligibility in various ways in the spirit of “compassionate conservatism.” But the Republican food-stamp-trashing caucus roared back to life under President Barack Obama, whom Newt Gingrich labeled “the most successful food stamp president in history.” He didn’t mean it as a compliment; more likely he meant it as a racial slur harking back to Reagan’s welfare-queen epithet. Tea Party Republicans and, later, Freedom Caucus Republicans tried to break in two the farm bills of 2014 and 2018 so that food stamps could be separated from farm programs and McCormack’s old left-right coalition be broken apart, but both efforts got halted in a Republican-controlled Senate.

The odd thing, Bosso said, is that “there’s no good evidence that SNAP disincentivizes work.” Two decades of studies have shown that work requirements are effective at kicking recipients off the rolls but not at getting those recipients to acquire a job. Yet Republicans keep at it. At this point we have to conclude the GOP long ago stopped caring about getting into the workforce that minority of able-bodied food stamp recipients who aren’t working already. All they want to do is take away their food.