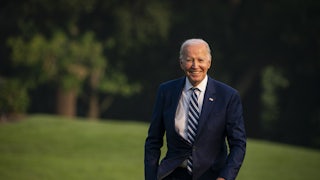

Last Thursday, on a visit to New York mostly for Democratic fundraisers, President Biden dropped by Rockefeller Center for a rare live, 20-minute interview with MSNBC’s Nicolle Wallace. He seemed as relaxed as I had seen him since inauguration, perhaps because he sat at a glass-topped table in a TV studio instead of amid the formality of the Oval Office or East Room.

Biden was, in fact, so laid back that he veered toward a topic that probably gave White House aides apoplexy: the media.

“Talking to a lot of reporters, they tell me,” Biden began, before warning himself, “I’m going to be careful of what I say.” But he continued, marveling at what a reporter for a major newspaper had once told him: “One of my editors in the newspaper came to me and said, ‘You don’t have a brand yet.’” A brand, Biden was told, was now necessary “so people will watch and listen to you because they think they know what you’re going to say.”

The president never fully completed the thought beyond noting, “There’s a lot changing.” But the subtext was clear: Biden is a twentieth-century guy struggling to survive in a twenty-first-century media environment. The problem transcends poll ratings, 2024 horserace numbers, and the failure of the president to get full credit for a buoyant economy. It cuts to the essence of his dilemma: How does a modern president, one who is neither especially charismatic nor extremely online, reach voters en masse?

For the longest time, the glib solution promoted by armchair experts was for Biden to command the nation’s attention with an Oval Office address. (Confession: I was one of the pundits peddling this panacea.) In early June, Biden finally spoke in prime time, from behind the Resolute Desk, about the bipartisan debt ceiling deal. And guess what? Less than a month later, almost no one remembers the speech.

None of the techniques that made Ronald Reagan the Great Communicator still work. In a streaming world, where more than half of American homes no longer have a cable subscription, there is no way for a president to rhetorically bestride the narrow world like a Colossus. But the problem is especially acute for Biden, who has made being boring a feature rather than a bug.

From the invention of radio to Biden, there has never been a presidency as simultaneously consequential and unexciting. It might be tempting to compare the Biden years with the quiet competence of the George H.W. Bush administration, which successfully managed the collapse of the Soviet Union. But Bush had minimal domestic ambitions. A chronicle of that administration by Mike Duffy and Dan Goodgame was aptly titled, Marching in Place: The Status Quo Presidency of George Bush.

Barack Obama had the reputation for being the epitome of “no drama.” But Obama was surrounded by a colorful cast of White House aides ranging from Rahm Emmanuel to Larry Summers. He also made the stunning choice of Hillary Clinton as his first secretary of state. Moreover, Obama was blessed with a vice president who had the temerity and the independence to upstage him on issues like gay marriage.

As a political figure whose worldview was shaped by New York City tabloids and his own fake real estate empire on reality television, Donald Trump proved to be made to order for our new media age, where the line between entertainment and reality has been all but eradicated. Trump’s Twitter account was akin to his speeches at campaign rallies. Americans followed Trump in either joy or horror, transfixed by what the real-estate huckster would say next and who would be his next victim.

Every president is, to some degree, the antithesis of his predecessor. Biden came to office determined to end the tantrums and the tempestuousness, the deceit and the dissembling of the Trump years. As a result, the internal workings of the Biden administration are so placid that probably more Americans know who won the Punic Wars (Rome) than the name of president’s chief of staff (Jeff Zients).

It is hard for anyone under the age of 50 to grasp how much the media environment has changed since Biden first ran for president in 1987. It was still a newspaper-dominated world, in which Biden as Delaware senator lived and died by the coverage not only in The New York Times and The Washington Post but also the Philadelphia Inquirer (which had national ambitions) and the News Journal in Wilmington. Television news in the 1980s was personified by three anchormen—Dan Rather (CBS), Tom Brokaw (NBC), and Peter Jennings (ABC)—who presided over 30-minute network evening newscasts at 6:30.

Aside from the anchormen, a handful of TV celebrity interviewers (Barbara Walters and Mike Wallace), and the occasional newspaper columnist (George Will), virtually no one in the news business was a brand in 1987. Without the existence of the internet, and with cable television news a fledgling concept pioneered by Ted Turner, there was far more of a shared media culture. People followed the news because that’s what most citizens did in a democracy. And the dominant idea was to trust the source of news (whether it was the Associated Press or CBS) rather than to look to it to buttress preexisting ideological suppositions.

To his credit, Biden is not clinging to a concept of the news media that no longer exists. I suspect that the president even knows that cable news is imperiled from cord-cutting and partisan predictability. With newspapers like the Times becoming an expensive niche product for elite audiences and local papers in free fall, there is a serious question, going into the 2024 election, about where most voters will get their news.

Republicans not named Trump face similar problems gaining national attention. The Nielsen ratings for the second quarter of 2023 contained ominous numbers for Fox News. Viewership among adults from 25 to 54 years old (a key political demographic) was down by 31 percent from the first quarter of 2023 and down by nearly 50 percent from a year ago. Yes, there remains a right-wing megaphone for news, but the evidence suggests that its range is shrinking as its decibel level rises.

Biden’s handlers should see the Nicolle Wallace appearance as an argument for the president to make more unscripted television appearances and grant far more print interviews. Yes, there is always a danger that a maladroit statement or some baffling syntax will go viral. But trying to replicate the 2020 pandemic-era campaign bunker in the coming presidential race will only foster conspiracy theories about Biden’s health. Ultimately the White House should trust in the president to make more off-the-cuff appearances because being unplugged was once the essence of Biden’s brand.