A strong case can be made that Vladimir Putin’s blood-soaked invasion of Ukraine has galvanized the American people like no foreign event since the 1989 breaching of the Berlin Wall and the subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union. Putin’s mad-tyrant drive has led to an outpouring of emotional support for the beleaguered Ukrainian people that is reminiscent of American attitudes in 1940 during the London Blitz.

In normal times, foreign policy is an elite preoccupation reserved mostly for those who find it riveting to sit through a two-hour panel discussion on the future of NATO at the Council on Foreign Relations. Average voters only notice foreign lands—with a few exceptions like Israel and Cuba—between the rally-round-the-flag period when American soldiers land and the tearful aftermath when U.S. casualties become too great to justify or sustain.

But Russia’s onslaught into peaceful Ukraine has created a rare moment when a mass-based American foreign policy is being forged on the spot. A new Quinnipiac University Poll found that 50 percent of Americans liken Putin’s move into Ukraine to “Adolf Hitler’s actions against Austria and Czechoslovakia before the outbreak of World War II.” That explosive Putin-Hitler comparison cuts across the political spectrum, with 49 percent of Republicans and 60 percent of Democrats accepting this equation. And a Reuters/Ipsos Poll released last week revealed that 84 percent of Americans were at least somewhat familiar with the war between Russia and Ukraine.

This is not normally the case, even when thousands of civilians are being slaughtered in Europe. In September 1992, when Sarajevo had already endured a five-month brutal siege by the Bosnian Serbs, only 37 percent of Americans said in a Times Mirror Poll that they were following the news in the Balkans. At the time, the Bosnian capital—which was described by The New York Times as a “wasteland” of “fire-gutted office towers”—should have been familiar to most TV viewers as the site of the Winter Olympics only eight years earlier.

The reasons for the bipartisan American embrace of the Ukrainian cause are both obvious and uplifting. The ubiquity of social media means that everyone can grasp Ukrainian suffering and heroism. And U.S. interest in the fate of Kyiv and other Ukrainian cities is partly explained by the good-versus-evil contrast between Volodymyr Zelenskiy and Putin. Tragedy has given the world an unshaven everyman actor morphing into Winston Churchill and a nearly hairless Russian leader transforming himself into the twenty-first-century version of Joe Stalin. Also, Moscow is a familiar villain for both those who recall the Cold War and those whose knowledge of geopolitics is shaped by action-adventure movies with merciless Russian oligarchs as the villains.

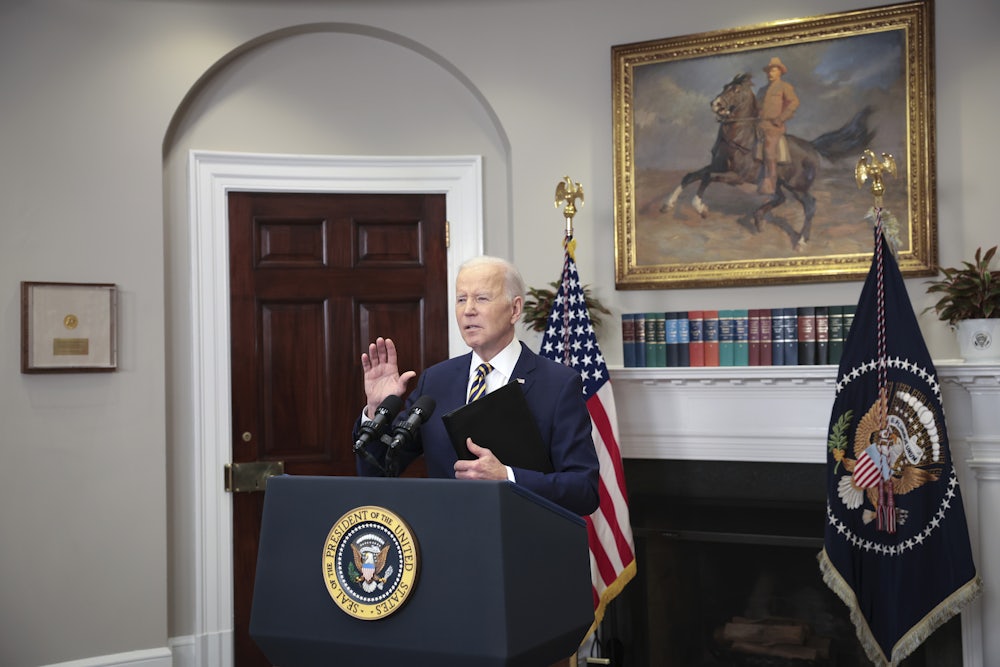

In short, this is—as Joe Biden would say—“an inflection point.” And while the president has done an exemplary job in managing the crisis, Biden has been too reticent in explaining the stakes to the American people. His updates on Ukraine have been—aside from the State of the Union, when he quickly detoured back to domestic politics—relatively brief daytime appearances in the White House watched in their entirety only by cable news devotees.

What Biden should do instead is to deliver the first Oval Office address of his presidency. And it should be devoted entirely to harnessing and shaping the current stunning level of national unity.

The Quinnipiac poll underscored the lengths that the American people will go to support Zelenskiy and the Ukrainian people—78 percent back admitting refugees into the United States, and 71 percent (including 66 percent of Republicans) would accept “higher gasoline prices” as a side effect of banning imports of Russian oil.

The poll question was asked before the president announced Tuesday that the U.S. would join the Russian oil boycott. Praising oil companies and other businesses for pulling out of Russia, Biden said in a line that evoked the shared sacrifice of World War II on the home front, “This is a time when we have to do our part.”

We are witnessing an unequivocal repudiation of the policies of a fake-tough-guy former president who purred at the sight of Putin. Now, according to Quinnipiac, 60 percent of Americans think that the Russian autocrat is “mentally unstable.” Even with $4-a-gallon gasoline becoming a bargain in most states, Americans say that they are willing to sacrifice for the greater good. And instead of more build-the-wall theatrics, Americans are willing to open the gates to Ukrainian refugees, who, admittedly, are overwhelmingly white.

This is Biden’s moment—and the president must seize it.

No setting carries the gravity and the weight of history as much as a president speaking in prime time from behind his desk in the Oval Office. This was the place from which John Kennedy warned America of the grave threat from Soviet missiles in Cuba. And the venue where George W. Bush chose to speak after the September 11 attacks.

Like Barack Obama before him, Joe

Biden bristles at the constraints imposed by the formality of such a

traditional setting. Biden’s rare prime-time appearances have been either

addresses to Congress or stand-up speeches almost always delivered from the

East Room of the White House.

In the midst of what may prove to be the most fateful weeks of his presidency, Biden must seize the bully pulpit of an Oval Office address. It is imperative for Biden to explain to the American people the lasting implications of Vladimir Putin’s brutal invasion and both the strength—and, sadly, the limitations—of America’s commitment to Ukraine.

Other presidents have used the Oval Office to declare war. Biden must carefully explain why—despite all the provocations—America and the other NATO nations cannot risk a direct military confrontation with an out-of-control nuclear power. The no-fly zone that Zelenskiy has been pleading for may sound appealing to armchair generals, but Biden must lay out the risks of U.S. airborne combat over Ukraine against Russian planes.

Such a prime-time speech on Ukraine would not be a replay of the State of the Union. Grafting 10 minutes on Ukraine at the top of the SOTU was designed to highlight the bipartisan unity of Congress in defiance of Russia aggression rather than to explain the dire realities in Ukraine to the American people. More than other forms of presidential communication, an Oval Office address can be—to grab a term from other contexts—a teachable moment.

Yes, the broadcast networks will inevitably grumble at the prospect of losing 30 minutes of prime-time revenue for a presidential address. But unlike many of his predecessors, Biden has not abused his presidential claim on a national television audience. Ronald Reagan, for example, delivered 16 evening speeches from the Oval Office, and Bill Clinton used this prime-time format 13 times.

The point of such an Oval Office speech would be to transcend politics. This is not a moment to calculate, as a recent Politico newsletter put it bluntly in a headline, “Will Biden get a Ukraine bounce?” Sometimes, good policy alone is its own reward. There will be plenty of time before November to place Ukraine and Biden’s robust response in an electoral context. But the president speaking to the American people from the Oval Office now might play a role in inoculating the Democrats against the inevitable Republican chorus blaming Biden alone for higher prices at the pump.

Seventy-five years ago, almost to the day, Harry Truman articulated what would become known as the Truman Doctrine, in a speech to Congress calling for aid to protect the governments of Greece and Turkey against being overthrown by the Communists. As Truman said at the time, “Totalitarian regimes imposed on free peoples, by direct or indirect aggression, undermine the foundations of international peace and hence the security of the United States.”

Now global peace and security are again on the line because of direct aggression by Moscow. The American people do not need something as grand as a Biden Doctrine. But they do need an Oval Office address by their president preparing them for the new and dangerous road ahead in both Ukraine and on the eastern flanks of NATO.

Even now, as cities like Kyiv have held out for nearly two weeks, the brave and creative resistance of the Ukrainian people has given the world reasons to hope. And once again, as Biden should stress, Americans are united in the cause of freedom with a fervor that pessimists could not have imagined even three weeks ago.