“There can be no genuine peace in the Middle East until the Arab states abandon the policy of hostility to Israel and show by deeds and words readiness to accept Israel’s right to exist,” Abba Eban, Israel’s ambassador to the United States, told the Overseas Writers Club in Washington in 1955. Sixty-six years later, Dani Dayan, the Israeli consul general in New York, wrote in The New York Times, “The day Palestinians accept Israel’s right to exist as the legitimate homeland of the Jewish people, a real peace process will begin.” Through the intervening years of wars, invasions, occupation, peace processes, and treaties, Israel’s right to exist has stubbornly endured. Just last month, the House of Representatives passed a resolution that “denying Israel’s right to exist is a form of antisemitism.” The phrase and its long history compels us to ask: What does it mean for a nation to “exist,” and who judges its right to do so?

Republican Congressman Chris Smith of New Jersey said recently that “Israel is the only state in the world whose fundamental right to exist, within any borders at all, is openly denied by other states.” But Israel is the only nation with a “right to exist,” as the phrase is not commonly attached to any other country. And that’s the tell: This is not a legal concept, but a political one, available for broad interpretation and rhetorical weaponization.

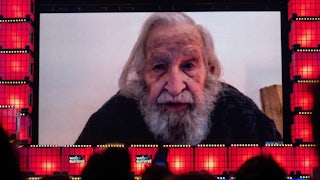

The “right to exist” as a nation is, as the Palestinian scholar Edward Said once wearily dismissed it, “a formula hitherto unknown in international or customary law.” Rights pertain to individuals, not countries. And universal rights can’t, by definition, belong to some peoples and not others. It’s one of the great ironies, then, of the Israel-Palestine conflict that Israel seems untouchable by international law as it actually exists—it suffers no sanctions for routine violations of Geneva Convention prohibitions against settlements in the occupied West Bank—but is so fulsomely protected by a statute of international law that is basically made up.

However intensely Israel feels under threat, its right to exist is meaningless as a matter of law. Its realest meaning is as a flexible piece of political rhetoric. One consistency in its use over the years is that Israel’s “right to exist” is always invoked negatively, as a thing someone somewhere denies or won’t accept. It’s most typically used to characterize Arab and Palestinian intransigence or dogmatism. After Israel’s resounding victory in the 1967 Six-Day War against Egypt, Syria, and Jordan, Egypt’s foreign minister told the press in obvious exasperation:

Perhaps we have not said this loudly enough or plainly enough.... That this document [the Egyptian-Israeli Armistice Agreement of 1949] would guarantee the right of Israel to exist is self-evident. We do know Israel exists, we have signed a piece of paper. We did not sign it with shadows.

Palestine Liberation Organization President Yasir Arafat sounded a similar note in 1988, after an official statement that the Palestinian National Council “accepted the existence of Israel as a state in the region.” “The PNC accepted two states, a Palestinian state and a Jewish state, Israel,” Arafat said. “Is that clear enough?”

Apparently, it was not. The specific meaning of the phrase relies a lot on things unsaid or implied: Both the nature of the supposed refusal and the implication that denying Israel’s “right to exist” means denying Jews’. It also depends a lot on the dependent clauses that come after that word: “as a state,” “in peace and security,” or “as a Jewish state”?

In 1993, as a precondition of the Oslo peace negotiations, the PLO recognized the “right of the State of Israel to exist in peace and security,” a declaration based on the 1967 U.N. Joint Resolution 242 that affirms every Middle Eastern nation’s “right to live in peace within secure and recognized boundaries free from threats or acts of force.” As the peace process collapsed, and Israeli politics moved sharply to the right, the country’s parliament passed its so-called “Nation-State Law,” which declared that “the exercise of the right to national self-determination in the State of Israel is exclusive to the Jewish people.” The goalposts of “existence” had moved considerably. Now Israel’s right to national self-determination—its national right to exist, if you like—seemed to explicitly reject Palestine’s. How could Palestinians accept this right without denying their own?

In a column in October, The New York Times’ Bret Stephens wrote of activists (many of them Jews) protesting Israel’s latest bombardment of Gaza: “‘Anti-occupation’ is opposition to Israel’s right to exist in any form.” Here, the “right to exist” is used to insinuate that those critical of Israel’s policies in Gaza are antisemitic. That is the rhetorical trap that Israel’s “right to exist” has always set for the country’s critics: On the one hand, reject Israel’s “right to exist,” and risk being accused of rejecting Jews’ human rights to exist; on the other, accept Israel’s right to exist and risk accepting whatever interpretation a future audience will choose to make of the phrase’s ever-changing meaning.

Questions of “existence” are typically left to theologians and philosophers, for good reason—pinning treaty obligations on issues of metaphysics is a recipe for confusion. So what can we say with honesty? Israel has no right to exist because no nation does; only people do. Israelis exist; so do Palestinians. They all have a right to exist but only because they are human beings. And there is no justice in securing your own right to exist by denying it to others.