In 2023, most large U.S. cities saw a precipitous drop in the rate of homicides. Despite the public perception of a rise in violent crime in major metropolitan areas, cities like Chicago and New York City saw dramatic declines in murders from 2022. But a few cities bucked that trend, including the nation’s capital. With the fifth-highest murder rate among the country’s most populous cities, Washington, D.C. has drawn national attention for its recent spike in violent crime.

The statistics are sobering: 2023 was the District’s deadliest year since 1997, with 274 recorded homicides. With 40 homicides per 100,000 residents—an increase of 35 percent from the previous year—D.C.’s high murder rate contrasted with falling levels in most other major cities, an ominous reminder of the District’s unofficial status in the late twentieth century as “America’s murder capital.” The high number of homicides was inextricable from gun violence, as the majority of these homicides were caused by firearms.

Violent crime in the District also increased dramatically in 2023, rising 39 percent compared to the previous year. Here, it’s worth noting that “crimes of violence” are definitionally broad under the D.C. Code, including robbery, burglary, and homicide; pickpocketing, for example, constitutes the same offense of robbery as being robbed at gunpoint. Nonetheless, the numbers are jarring: In 2023, there were 959 reported carjackings. Juveniles and teenaged adults constituted the majority of the arrests for carjacking, according to Matthew Graves, the U.S. attorney for D.C.

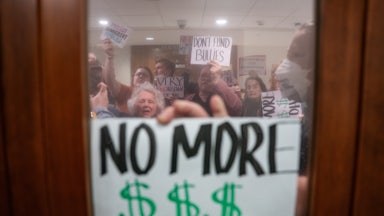

As the problem of crime in D.C. has garnered national attention—due in part, no doubt, because of its status as the nation’s capital and seat of government—politicians in D.C. have found themselves on the defensive. Several District officials, including Mayor Muriel Bowser, have recently testified before Congress. In March 2023, the D.C. Council withdrew legislation that would have updated its criminal code, largely because of opposition from House Republicans and many congressional Democrats. The District is unique in that laws passed by the Council must be reviewed by Congress, further granting the issue of crime in D.C. national political salience.

But understanding the spike in violent crime in D.C.—which itself often involves guns—is not a simple task. Criminal justice experts believe that considering violence in the District must involve an examination of the structural problems that have left its most vulnerable residents behind.

Structural Causes

Issues of racial inequality and gentrification are not unique to D.C., but they are particularly intense in the District. Once known as “Chocolate City” due to its majority-Black population, the District has seen a dramatic change in demographics in recent decades, with Black residents accounting for only 45 percent of the city’s population in 2022. “If you look at D.C. in the year 2000, for example, there were no low-income white neighborhoods. So gentrification in D.C. is always a racialized process,” said Tanya Golash-Boza, the executive director of the University of California, Washington Center and the author of Before Gentrification: The Creation of DC’s Racial Wealth Gap.

When higher-income, primarily white residents move into redeveloped neighborhoods, it is the Black residents who are displaced, said Golash-Boza. Compared to their white counterparts, Black residents of the District are more likely to live in poverty and be unemployed, disproportionately live in neighborhoods that experience higher rates of homicide, and even lack sufficient access to health care. All of these factors contribute to a sense of “relative deprivation,” said Golash-Boza. “The idea is not just that you’re poor but also that you can see other people around you with more,” she said.

The Navy Yard neighborhood in southeast D.C., for example, has experienced radical change in the past 20 years. In 2005, Navy Yard had a similar profile to Anacostia, the area of D.C. just across the Anacostia River. But in the intervening years, it has experienced rapid redevelopment, becoming a site for a Major League Baseball stadium, luxury apartments, and trendy restaurants and bars. Not only have the primarily Black residents who used to live in Navy Yard been displaced, the residents of Anacostia—which has been hardest hit by rising violent crime rates—can look across the river and see development that isn’t occurring in their own neighborhood.

Physical, social, and cultural displacement is a major throughline for the experiences of Black residents of D.C. During the twentieth century, Black citizens of the District were subject to “redlining,” the historic practice of refusing loans to certain applicants based on race, entrenching them in low-income neighborhoods. But when that land became valuable, said Joseph Richardson, a professor at the University of Maryland who researches gun violence and trauma, “their homes are then razed and they’re displaced.”

“That destabilization of communities is happening all around D.C., and I don’t think you could expect—in these totally destabilized communities—to not have a negative effect that comes out of that,” Richardson said. “That could be gun violence, that could be crime, that could be carjacking—but I don’t think in any space, in any city in the country, you could engage in that level of rapid displacement without it having an impact.”

Poverty itself can be a kind of risk factor for involvement in crime. Patrice Sulton, the executive director of the DC Justice Lab, recalled meeting with clients in her previous career as a defense attorney. If a client went a significant period of time without being incarcerated or otherwise involved with the criminal justice system, it was typically because they had managed to obtain a job during the intervening time or had gained access to mentorship if they were a juvenile. She argued that indicators of poverty, such as food insecurity, were connected to their likelihood of exposure to crime.

“It should be obvious that it’s dangerous to live in a city where you have over 100,000 people who don’t have enough food,” said Sulton.

How Youth Are Affected

There has been particular consternation about an apparent rise in youth involvement in violent crime. The headline statistic, of course, is that jarring revelation by the U.S. attorney’s office that juveniles and teenage adults constituted the majority of the arrests for carjacking in 2023.

It’s worth taking these statistics with a grain of salt: Kristin Henning, a professor at Georgetown Law and director of the Juvenile Justice Clinic and Institute at Georgetown Law, noted that the Metropolitan Police Department had a relatively low closure rate for carjacking cases, meaning that it’s difficult to tell with certainty who is committing the most crimes. Most violent crimes, she continued, are driven by adults, with carjackings as an outlier.

“Young people are far more likely to get caught,” said Henning. “To the extent that we use that kind of data to demonize children—and to be clear, in the District of Columbia, that means demonizing Black children—we have to be really, really careful.”

Nonetheless, the involvement of youth in violent crime, whether as victims or perpetrators, is a disturbing trend. Nineteen children and teenagers were killed in 2023, 16 of them by gunfire. Violence intervention advocates on the ground have described a youth culture defined by social media feuds that spill out into the real world, as well as an underground rap scene that can inflame conflicts. (D.C. implemented a youth curfew in December, despite evidence from other cities that such policies do not reduce crime.)

Relatively easy access to firearms complicates the issue. Although the District itself has relatively strict gun laws, many D.C. residents—including young people—are easily able to obtain firearms from outside of the city. For many teenagers living in areas with high rates of violent crime, there is a persistent belief that they need to obtain guns to protect themselves.

“So many of the young people who come into the juvenile legal system aren’t the shooters, they aren’t the killers, they aren’t the ones who are violent, even if they have a gun,” said Henning. “Many of them now have guns for their own safety [but] are shaking like a leaf or terrified to even have it on their person.”

Displacement and poverty may exacerbate those factors that could turn youth to violence. Jawanna Hardy, the founder of Guns Down Friday, a D.C.-based violence intervention group, recalled working with a young man who preferred being incarcerated to his life at home.

“He came home, and two weeks later he was locked back up again. Not because he’s a bad kid. When he came home, he went right back to the streets, because there were no programs for him,” Hardy said.

Advocates believe that the struggles faced by young people in D.C. are precipitated in part by a relative lack of access to recreation and mentorship programs and to mental health support, particularly in schools. The coronavirus pandemic only exacerbated these trends.

The pandemic was devastating for children across the country, with school closures affecting their academic performance and social development. But it was particularly dire in D.C., where so many children live in poverty. Whereas a child in a middle-class household in the suburbs might have their own bedroom to use as a remote classroom and could play outside during the pandemic, a poor child in Washington, D.C., could be living in a very small apartment with no privacy.

“So the impact of poverty literally drives children outside in ways in which they are subjected to the impulsive whim of delinquent acts,” Henning said.

Insufficient Investment

Many criminal justice advocates in D.C. believe there is a lack of proper investment in preexisting violence prevention programs, as well as a seeming disinterest in implementing new policies to address the root causes of gun violence and crime.

The office of the D.C. attorney general and the mayor’s office each have so-called “violence interrupter” initiatives, which deploy community-based individuals rather law enforcement to deescalate violence. While ambitious in scope, these programs are far from perfect: Having two separate offices administering violence interruption programs can make the response disjointed. Moreover, some violence interrupters are not adequately trained, or may not be responsive in times of need.

“In school, you know, you might have 50 teachers, and out of those 50 teachers, 10 of those teachers are excellent teachers that the kids want to work with,” said Hardy. “It’s the same with violence interruption. They have a handful of people that are really doing an awesome job, and then you have people who are just collecting a check, and no one’s holding anyone accountable.”

The District has also been rocked by several changes in leadership in recent years, which in turn affects the approach to addressing crime. Since 2016, there have been four chiefs of the Metropolitan Police Department, including one interim chief. The current chief, Pamela Smith, was formally confirmed by the Council in November. The city’s violence prevention efforts were also rocked by tragedy, when Linda Harllee Harper, the beloved director of the Office of Neighborhood Safety and Engagement, died unexpectedly this past summer.

“I think personnel really matter,” said D.C. Council Chair Phil Mendelson in an interview, adding that quality of leadership “is a subtle but significant factor.” He also expressed some frustration with Bowser, saying that she “has not been helpful in frequent press conferences which just create more public concern and suggest that the answer here is passing tougher laws.”

Meanwhile, the relationships between federal and local agencies can be rocky. In 2022, federal prosecutors in the U.S. attorney’s office in D.C. opted not to prosecute 67 percent of arrests that would have been tried in D.C. Superior Court. At the time, Graves, the U.S. attorney, cited multiple reasons, including the lack of accreditation for D.C.’s crime lab. The lab won back its accreditation at the end of last year, which in theory should make it easier to prosecute crimes.

Another difficulty is in determining appropriate targeting for violence prevention. A 2022 report by the National Institute for Criminal Justice Reform, or NICJR, found that around 500 identifiable people comprise roughly 60 to 70 percent of all gun violence in D.C. Also in 2022, the NICJR released a report including recommendations for reducing gun violence in the District. In December, Mendelson introduced legislation incorporating recommendations from this report, including a “focused deterrence” strategy that would allow law enforcement to target repeat violent offenders. Such a program has had success in other major cities, such as Boston. (Smith, the police chief, has emphasized “hot spot policing”—allocating officers to areas experiencing the most crime.)

In an interview, Mendelson said that this proposal—which would require the mayor to move forward with policies already largely within their power to administer—would supplement preexisting programs.

Mendelson gave the example of a John Doe, a known repeat violent offender. “The violence interrupter may reach out to work with him, to counsel him, to redirect him,” Mendelson said. “Law enforcement would be on the lookout for him committing another offense, and getting him locked up and prosecuted with swift and certain justice.”

The D.C. Council—like any other legislative body—is rife with clashing political agendas. Multiple council members, as well as Bowser, have offered individual legislation to address crime, complicating the passage of any one bill. Bowser’s proposals include the Addressing Crime Trends Now Act, which would create penalties for “organized retail theft” and allow the Metropolitan Police Department Chief to declare “drug-free zones” intended to prevent open-air drug deals. She has also called on the Council to pass a permanent version of her Safer Stronger Amendment Act, emergency crime response legislation that passed last year.

“In 2024, we are focused on additional policies, policing strategies, and strategic partnerships needed to reduce crime and increase safety in all eight Wards,” said Lindsey Appiah, deputy mayor for public safety and justice, in a statement.

It’s unclear whether 2024 will be an improvement on 2023. As of January 5, there have been two homicides in the District—the same number as at this point last year. Richardson, the University of Maryland, questioned whether there is the “political will” to address the structural factors that underlie the numbers.

“You could take a 15, 20 minute drive to another section of the city and gain 20 years of your life. And that’s not just the result of gun violence, that’s the result of structural racism and oppression,” Richardson said. “It’s not just about who died, it’s about who was left for dead.”