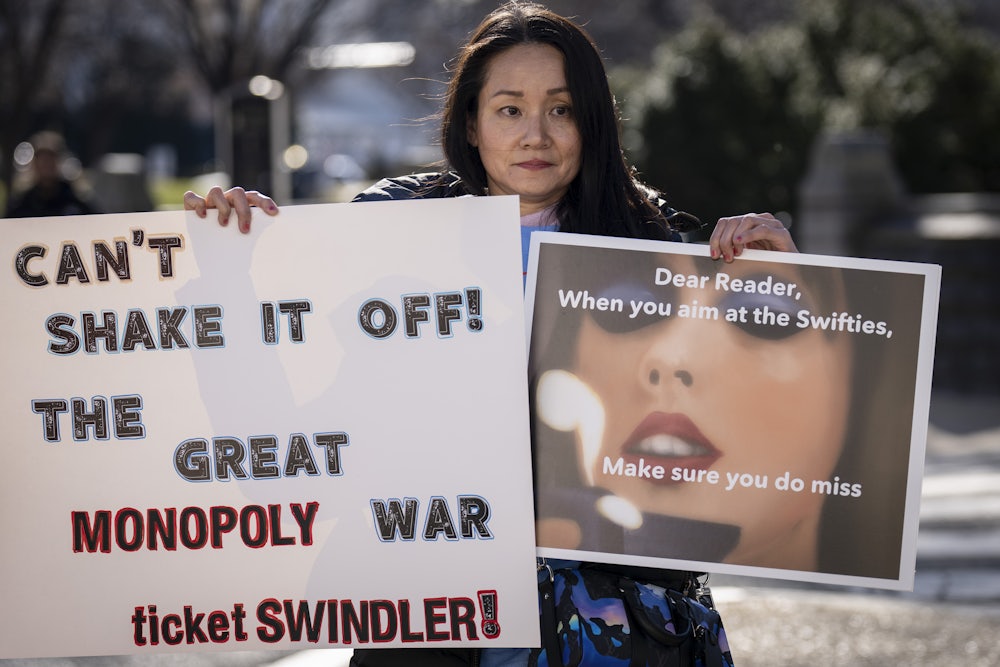

In a contrarian news analysis published earlier this week, David Leonhardt of The New York Times argued that a “flurry of bipartisanship” in recent years—legislation on infrastructure, semiconductors, arms to Ukraine, Chinese ownership of TikTok, etc.—heralds “a new form of American centrism.” I think Leonhardt oversells this: The most significant of these bills passed while Democrats had unified control of Washington. But he is right that Democrats and Republicans do find common ground on certain topics these days—such as loathing the concert promoter Live Nation Entertainment and its subsidiary Ticketmaster.

When the Justice Department sued Live Nation on Thursday for antitrust violations, it did not act alone. It was joined by attorneys generals for 29 states and the District of Columbia, including (predictably) California and New York but also Texas, West Virginia, Tennessee, and South Carolina—all states where Republicans control the governorship and the state legislature. In the matter of outrageous fees charged at concert venues, there’s not a liberal America and a conservative America. There’s the United States of America.

Live Nation, which pulls in $22 billion in annual revenue, is a cartoon monopoly. It “controls around 60 percent of concert promotions at major concert venues across the country,” according to the DOJ complaint, either through long-term contracts or direct ownership. Ticketmaster controls ticketing at about 80 percent of these same concert venues “and a growing share of ticket resales in the secondary [i.e., scalpers’] market.” One arm of Live Nation controls supply (the talent), while another manipulates demand (the audience).

It’s not against the law to possess a monopoly, but it is against the law to behave in an anticompetitive manner, as monopolies always do. The DOJ says Live Nation did this by turning a potential competitor, Oak View Group, which controls 400 venues worldwide, into a partner. Oak View Group, the government says, avoids bidding for the same talent as Live Nation and describes itself as Live Nation’s “pimp” and “hammer.” The complaint includes this “recent” communication from Oak View Group’s chief executive, Tim Leiweke, to Live Nation’s chief executive, Michael Rapino: “I always protect you on rebates, promoter position, ticketing.” Ouch.

Live Nation has also, the complaint says, “influenced” venues “to sign exclusive agreements with Ticketmaster.” And Live Nation “successfully threatened financial retaliation” against the private equity firm Silver Lake, compelling Silver Lake to direct its subsidiary TEG not to compete with Live Nation for promotion contracts in the United States.

Live Nation commits concert venues to long-term contracts that “prevent new and different promotions and ticketing competitors and business models from emerging.” It then uses its control or ownership of concert venues to compel artists to purchase its promotion services (i.e., its bookings at other venues). Also, the company uses its promotion muscle to compel arenas to use Ticketmaster. Live Nation’s Rapino more or less admitted this in astonishingly brazen statement at a 2019 Goldman Sachs conference that’s quoted, and partially bolded, in the complaint:

We can’t say to a Ticketmaster venue that says they want to use a different ticketing platform, ‘If you do that, we won’t put shows in your building.’ … [But] we have to put the show where we make the most economics, and maybe that venue [that wants to use a different ticketing platform] won’t be the best economic place anymore because we don’t hold the revenue.

Nice little amphitheater you got there. Too bad if something were to happen to it.

Under the “consumer welfare” standard that most courts still follow on antitrust—a standard developed by Robert Bork that the Biden administration considers insufficient—plaintiffs have to demonstrate that the company’s bad behavior harms consumers. That will not be difficult in the case of Live Nation. Ticketmaster uses its monopoly power to attach all kinds of cockamamie fees to the tickets it sells—the DOJ complaint mentions service fees, VIP fees, Platinum fees, Pricemaster fees, per-order fees, payment processing fees, and facility fees. In a 2022 segment about Live Nation, HBO’s John Oliver said his researchers found a 2019 ticket to a concert by Kidz Bop, a children’s pop music group, where the fees added 75 percent of the ticket value to the total cost; another for a 2022 concert by the rapper Tyler, the Creator where the fees added 78 percent; and a third for a 2019 ticket to a Monster Jam truck rally where the fees added more than 100 percent. Live Nation is so ubiquitous that its sworn enemy, Oliver, can’t avoid using it as he makes live appearances around the country.

Live Nation’s market power, the DOJ says, creates “a diminished incentive to innovate” that reduces customer service and product quality. That criticism isn’t new. In a 2010 Wired story, Steve Knopper related the David and Goliath story of how Ticketmaster was born. In 1976 two nerds working on a primitive computer at Arizona State University, Peter Gadwa and Albert Leffler, invented a ticket-selling program for ASU’s performing arts center that proved so successful they were able eventually to take down Ticketron, the reigning ticket seller for concert arenas through the 1980s. In addition to building a better mousetrap than Ticketron, Ticketmaster created a new, more extractive business model. Where Ticketron had charged concert venues for its services, Ticketmaster paid concert venues by adding ticket fees that it split with the house. It also paid venues large fees up front in exchange for multiyear exclusive ticketing rights. Thus did entrepreneurs devolve into rentiers. “The underlying technology,” observed Knopper, “barely changed.” It didn’t have to.

When Live Nation and Ticketmaster announced they would merge in 2009, the Obama Justice Department sued to block it, joined by many of the same states (including California and Texas) that have signed onto the new complaint. But the following year the Justice Department signed a consent decree that allowed the merger to go through under certain conditions. Live Nation, unsurprisingly, violated these conditions and was compelled to pay a $3 million fine. In 2020 the consent decree was extended five additional years. After the 2022 dustup over Ticketmaster’s alleged price gouging with Taylor Swift tickets, the DOJ once again investigated possible violations of the consent decree, but in the end the department decided to go back to square one, concluding that “Live Nation and Ticketmaster have committed additional, different and more expansive violations of the antitrust laws.”

I’m no lawyer, but this case looks to me like a slam dunk in court. And in the court of public opinion, where I can claim more expertise, it can’t lose.