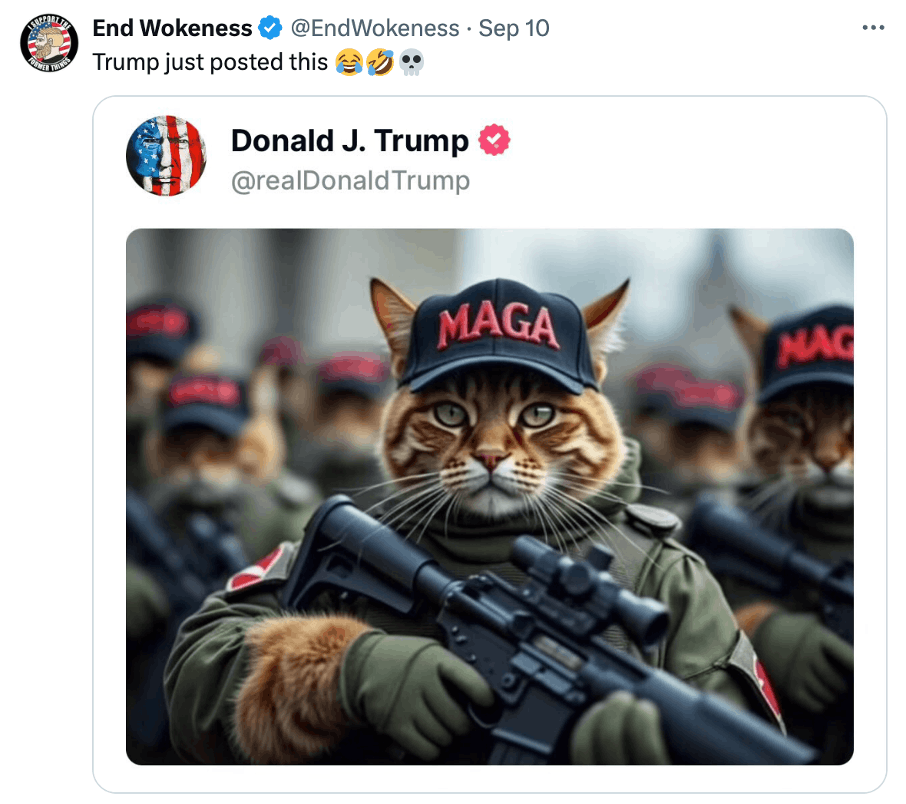

There was some surprise on Sunday when vice presidential nominee J.D. Vance argued that the “American media totally ignored” the plight of Springfield and Vance’s own claims about immigration “until Donald Trump and I started talking about cat memes.” He seemed to suggest that it was OK to use a false story if it made people pay attention. “If I have to create stories so that the American media actually pays attention to the suffering of the American people,” he thundered to Dana Bash, “then that’s what I’m gonna do.”

Even before Donald Trump screeched about cats and dogs on the debate stage last week, Vance took to X to encourage his followers to keep spreading debunked claims about Haitians eating cats: “Don’t let the crybabies in the media dissuade you, fellow patriots. Keep the cat memes flowing.” Such racist claims were worthwhile, Vance asserted, because it was “confirmed” that “a child was murdered by a Haitian migrant who had no right to be here,” a reference to the accidental death of an 11-year-old boy in a car accident with a legally admitted but unlicensed Haitian immigrant driver last year.

In other words: It was worthwhile to spread cat memes, Vance argued, because it brought attention to other claims that are also false (claims that the boy’s father has begged people to stop making).

Vance’s proud adoption of spreading false memes may have shocked people. But if you’ve been watching these people as closely as I have over the years, you know it’s not new. The ploy of using false memes to direct mainstream media attention has a storied tradition. For years, right-wing internet influencers—self-described trolls—have deliberately aimed to use “shitposting” to get the mainstream media to cover their favorite topics.

Details of this ethic, and how it can be used to sway an election, came out in the 2023 trial of right-wing influencer Douglass Mackey.

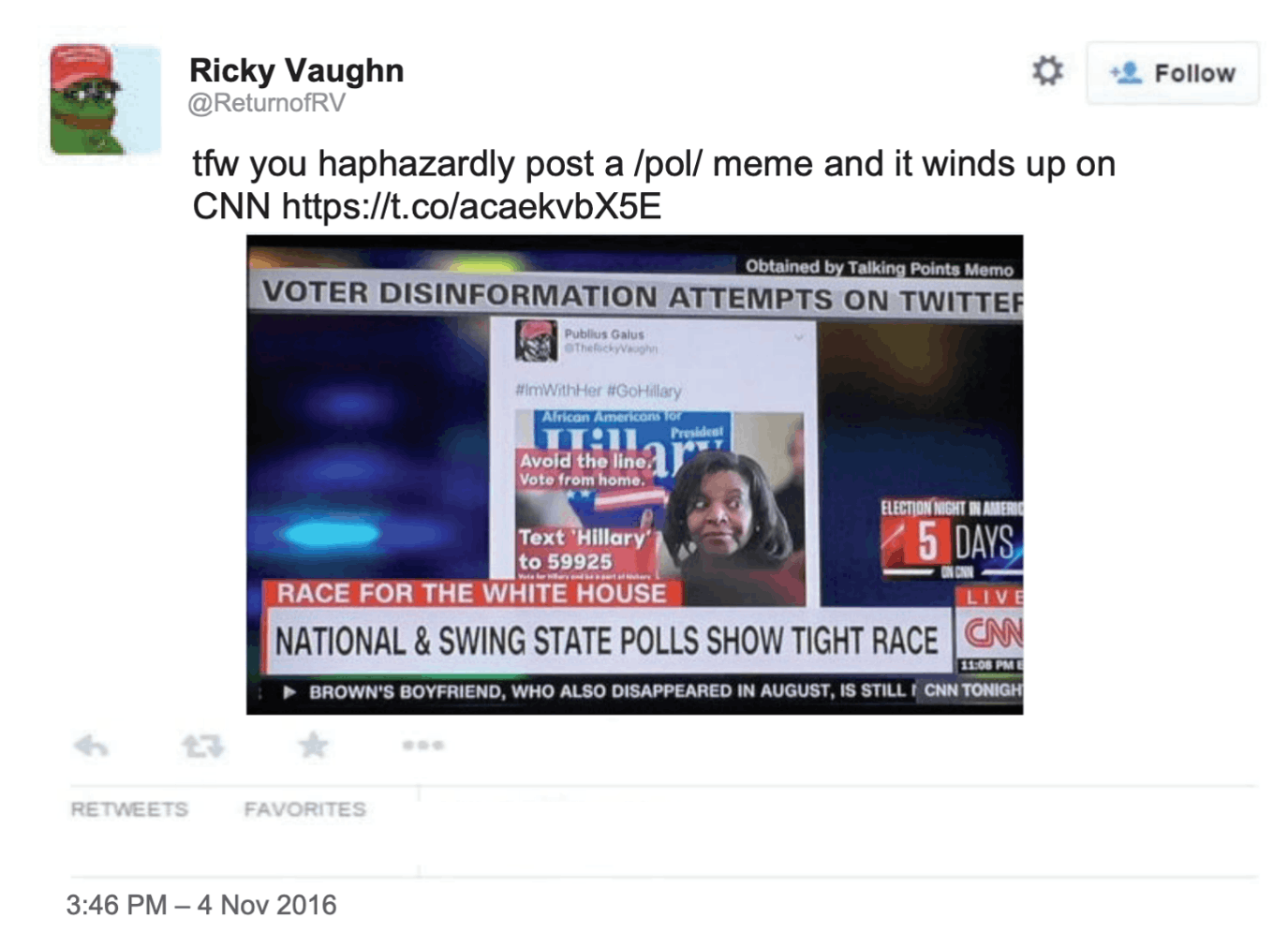

In 2016, Mackey used his popular Twitter persona, “Rickey Vaughn,” to induce Hillary Clinton supporters to text their vote rather than cast a legal vote in person. Mackey deliberately pitched his hoax to women voters of color, including Spanish speakers.

Mackey was charged and convicted of conspiracy to violate people’s right to vote, under Section 241 of Title 18 of the United States Code, and sentenced to seven months in prison. He remains out on bail pending an appeal.

At trial, prosecutors used the planning from chat rooms in which Mackey participated and testimony of Mackey’s co-conspirator, who testified pseudonymously under the name Microchip, to explain how the trolling efforts worked.

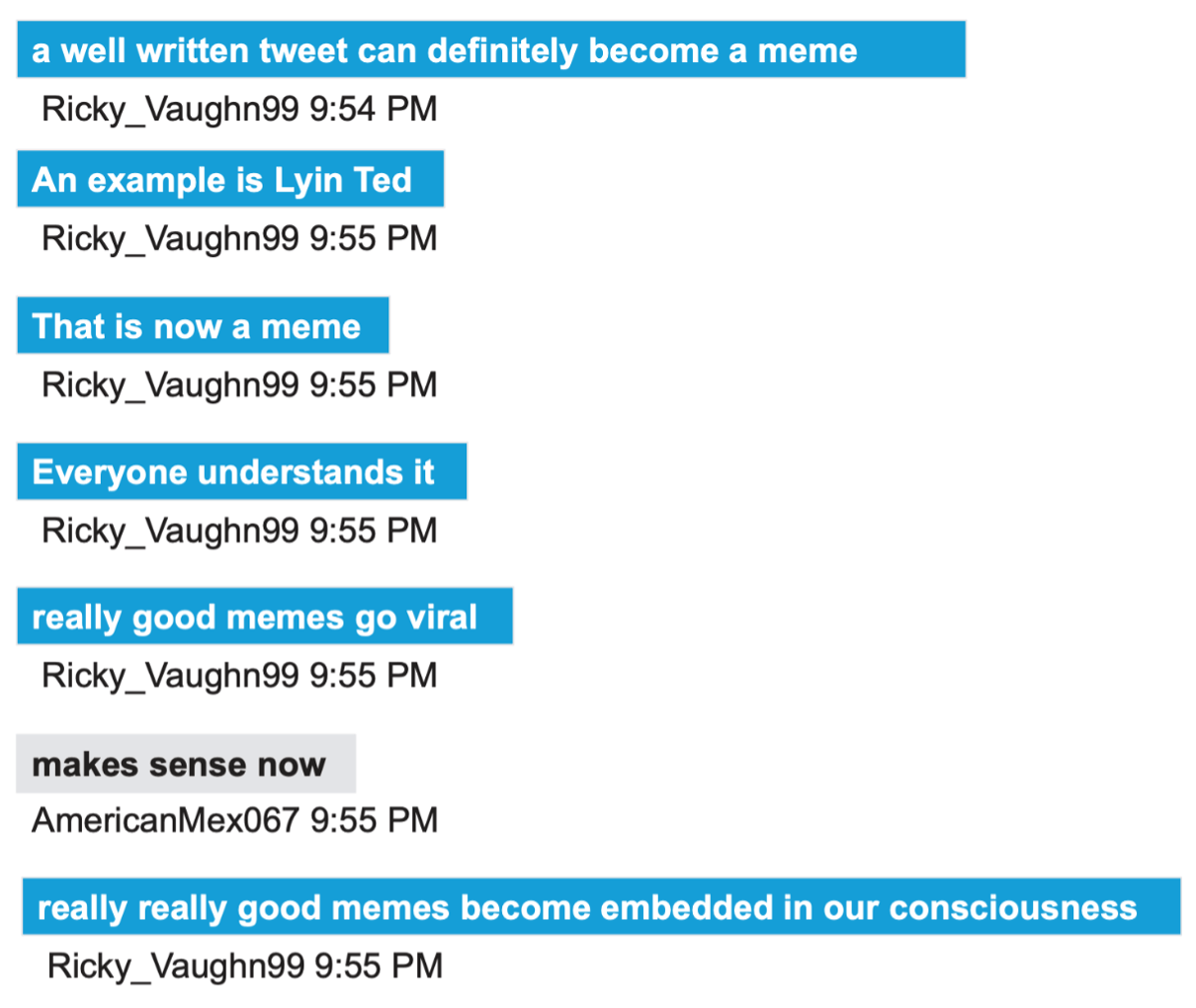

Microchip described how these chat rooms gamed Twitter’s algorithm to get things trending so journalists would cover it: “I wanted our message to move from Twitter onto regular society” so journalists would “develop stories based on it.” He (and Mackey, who took the stand) described how they’d take memes developed in far-right chat rooms on 4Chan or Reddit and make them go viral on Twitter. They used memes—very much like the various cat memes the former president posted on his social media account—because “people when they’re laughing, they’re very easily manipulated.”

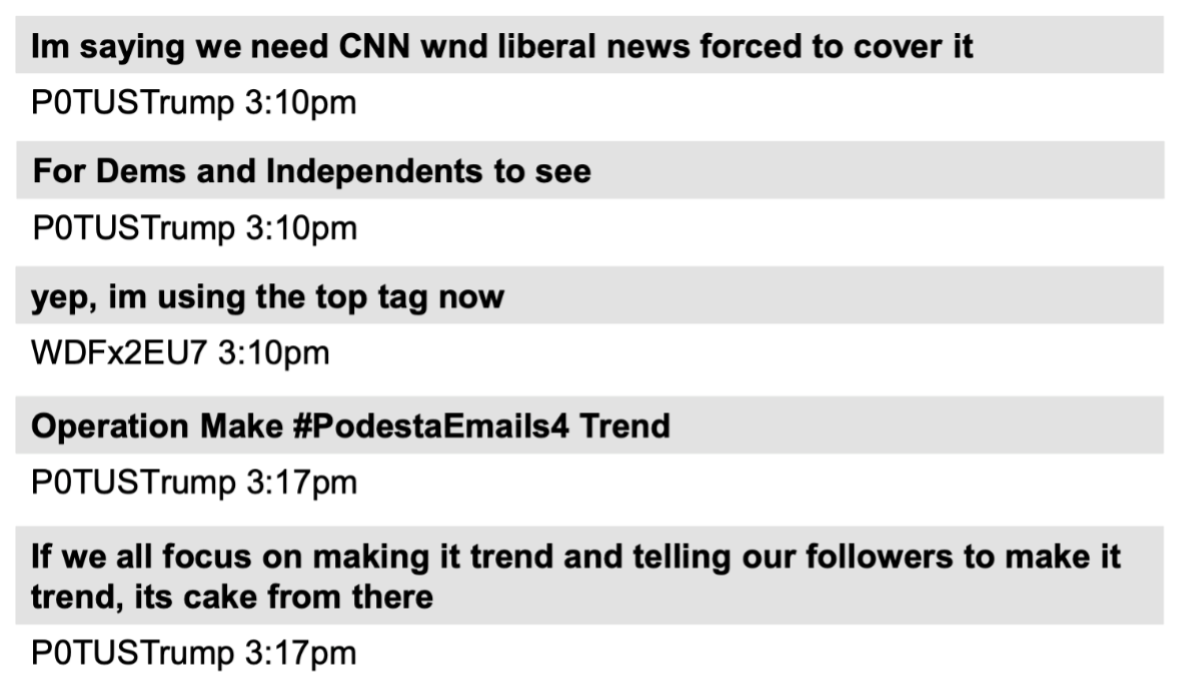

When a prosecutor asked about his role in making John Podesta’s emails go viral back in 2016, Microchip admitted that the emails “didn’t … have anything … particularly weird or strange about them, but my talent is to make things weird and strange so that there is a controversy.”

“Did you believe what you were tweeting was true?” federal prosecutor Bill Gullotta asked about the Podesta emails. “No,” Microchip answered. And like Trump’s veep candidate, he “didn’t care.”

As Microchip admitted on cross-examination, “Disinformation sometimes does increase buzz.” They’re even telling some of the same lies. In 2016, trolls photoshopped pictures to claim that singer Lana Del Rey endorsed Trump; this year, they’re using A.I. to claim Taylor Swift did.

The trolls had tried to professionalize their efforts months earlier, well before even their efforts to damage Trump’s primary opponents during the spring of 2016. Andrew “Weev” Auernheimer, at one time the webmaster for American neo-Nazi website Daily Stormer and posting under the name “rabite,” proposed to Mackey that they develop a book on trolling, so they could “hand people a fucking manual for psychological loldongs terrorism” (a made-up phrase suggesting they were using memes—something you LOL at—as terrorism). Weev’s goal was conversion: “i am absolutely sure we can get anyone to do or believe anything as long as we come up with the right rhetorical formula and have people actually try to apply it consistently.”

Mackey used an attack Trump wielded against Ted Cruz—one of the dumb nicknames that Trump workshops for all his adversaries—to explain how meming works to embed ideas in people’s consciousness.

The trolls played to other aspects of human psychology too, such as the fact that “people aren’t rational. a significant proportion of people who hear the rumour will NOT hear that the rumour has been debunked,” a woman treated as a co-conspirator in the trial advised, using the British spelling for rumor. By that logic, a chunk of people will continue to believe that migrants are eating pets, even after Dana Bash and the rest of the media have solidly debunked it.

In 2016, trolls measured their success precisely the way Vance does: getting a meme picked up by CNN.

There’s no evidence that Vance himself ever participated in these chat rooms. But these chat rooms had close ties to Trump. Even before Trump won the Republican nomination, right-wing influencer Anthime Gionet, posting under the moniker “Baked Alaska,” invited Mackey to join the “Trump HQ Slack.”

And in an interview with Mackey last year, Donald Trump Jr. admitted that he had been added to the chat rooms. There’s even a persona on the lists who used the moniker “P0TUSTrump,” whom others called Donald, who pushed the John Podesta leaks in the same days that WikiLeaks encouraged Don Jr. to disseminate them. That user aimed to use the same trolling method to “Make #PodestaEmails4 Trend” so that “CNN [a]nd liberal news forced to cover it.”

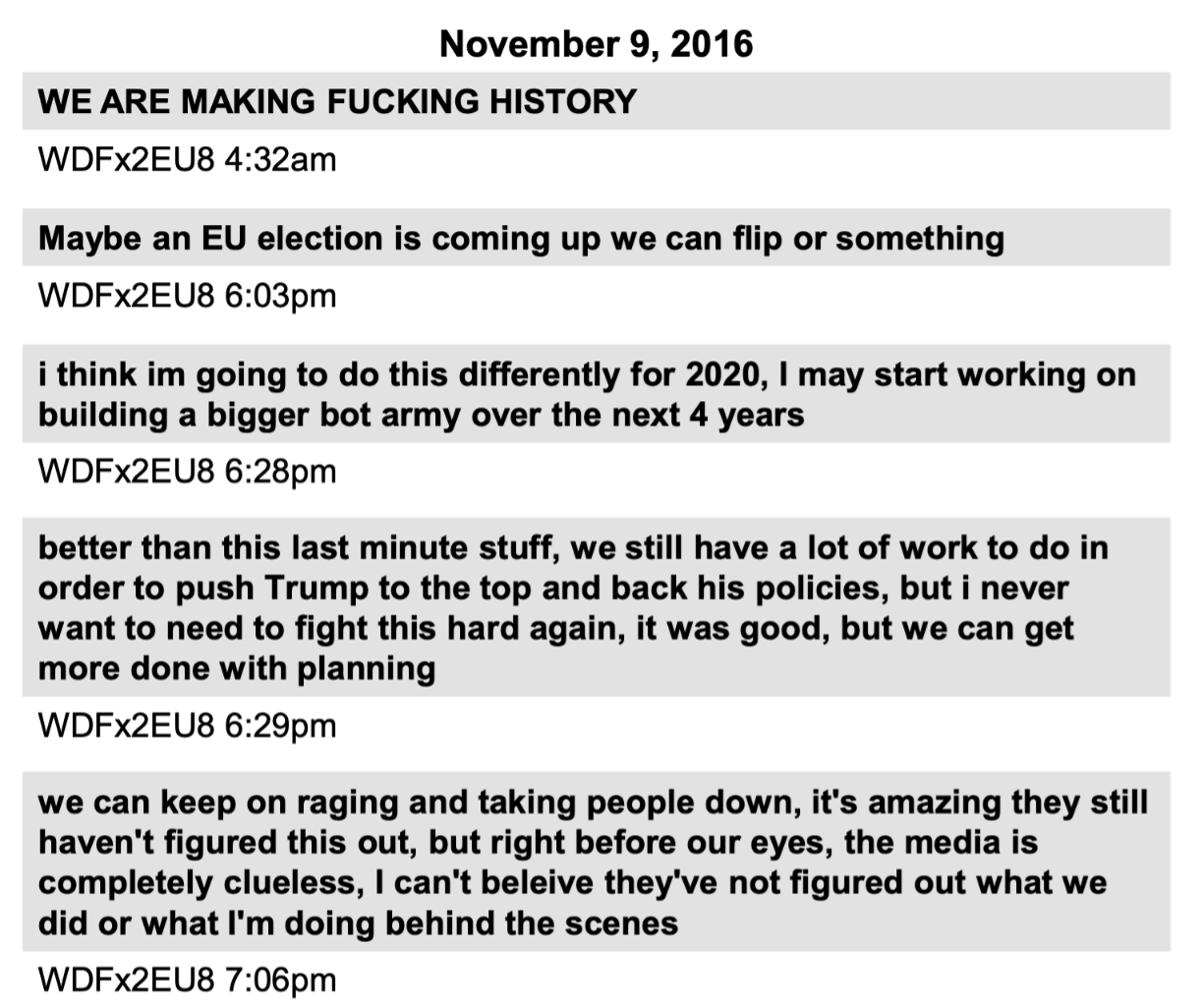

It’s easy to dismiss all this meming as juvenile play. But immediately after Trump won in 2016, Microchip (posting as “WDFx2EU8”) turned to further professionalizing the effort, with plans to do it again in 2020.

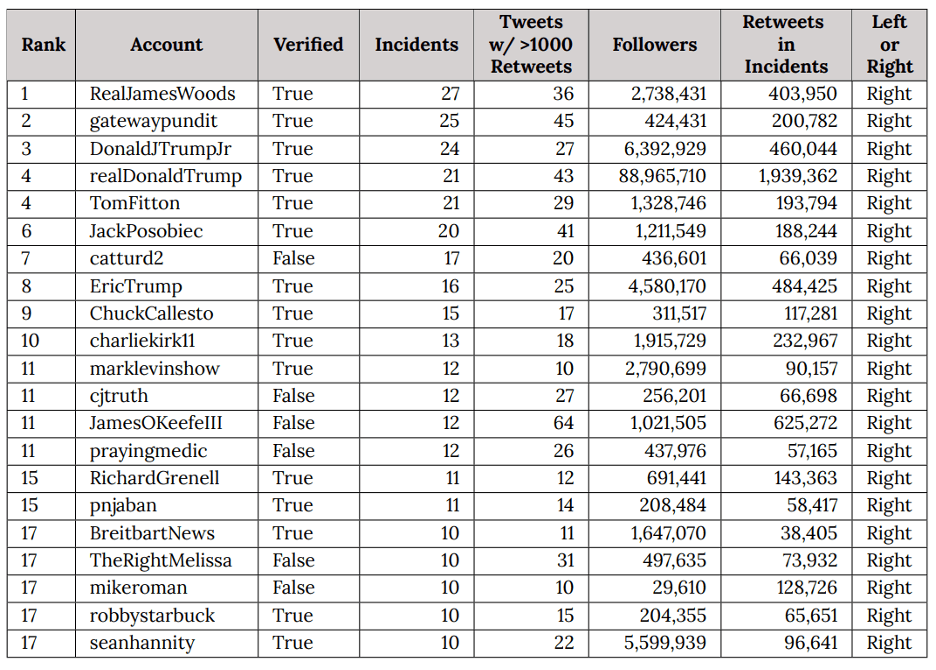

That effort may have borne fruit. In 2020, the deliberate dissemination of disinformation on Twitter played a central role in Donald Trump’s efforts to spread his Big Lie that he had been defrauded out of an election win. A retroactive study by Stanford’s Election Integrity Project of the false claims that had gone viral during the 2020 election found that Trump’s lies, including false claims about Dominion voting machines and the meme “Stop the Steal,” had the most reach. And Trump, his two older sons, his close allies Jack Posobiec and Charlie Kirk, his former Acting Director of National Intelligence Rick Grenell, and his Georgia co-conspirator Mike Roman were all among the most efficient disseminators of election mis- and disinformation on Twitter. Here is the Stanford study’s list of repeat spreaders of election misinformation:

Stop the Steal organizer Ali Alexander told the January 6 committee that his effort to organize the rally that would turn into the January 6 attack on the Capitol grew out of a similar Twitter chat D.M. group, testimony corroborated by influencer Brandon Straka.

Now, heading into his third election, the former president has his own social media site, a veritable workshop for this kind of attention-getting meme.

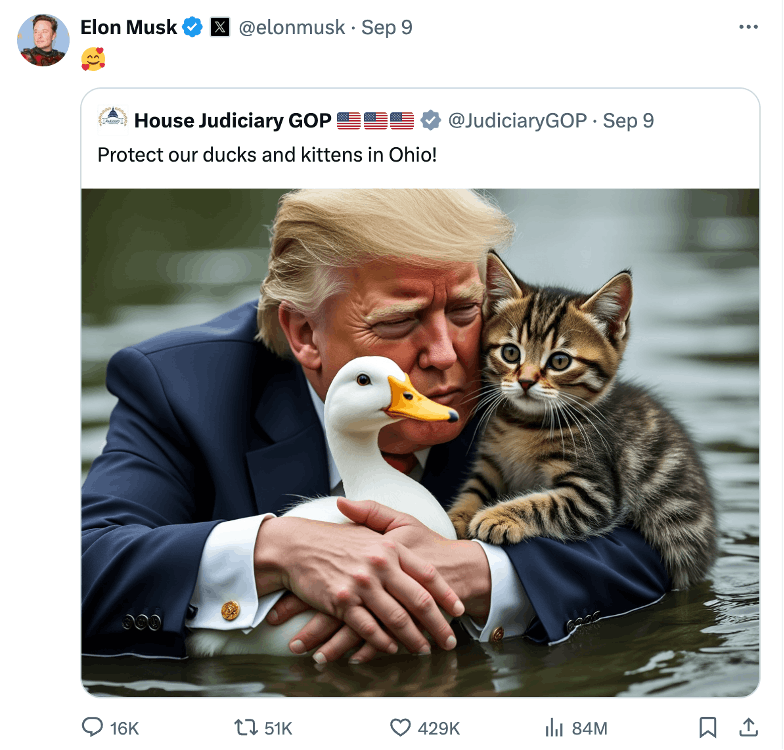

And since Elon Musk purchased Twitter, he has not just welcomed far-right extremists back on his site, but he has been a key vector for racist memes himself.

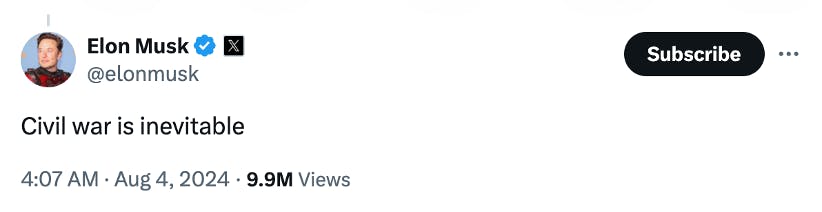

During recent anti-immigrant riots in the U.K., Musk played an even more central role in stoking violence, talking about civil war even as rioters targeted immigrants.

These A.I. images of Trump with kittens may seem harmless. But they’re part of a tradition of racially motivated election interference, with overt participation from self-described adherents of the far right.

That remains true. After Trump made the slur against Haitians go viral, adherents of a neo-Nazi group active in Springfield, Blood Tribe, took credit for making the meme go viral on social media sites Gab and Telegram before it was lifted by the End Wokeness account to X, much like Microchip and Daily Stormer webmaster Weev took credit for making things from 4Chan go viral eight years ago.

Vance, Trump’s blogger turned senator running mate, may not have grown out of the far-right chat rooms to which Trump’s son got added, but his ethic is the same: to use seemingly harmless memes normalizing false claims to force the mainstream media to adopt a far-right frame for an event, as has happened in Springfield. Imagine what we’re in store for over the next 50 days.