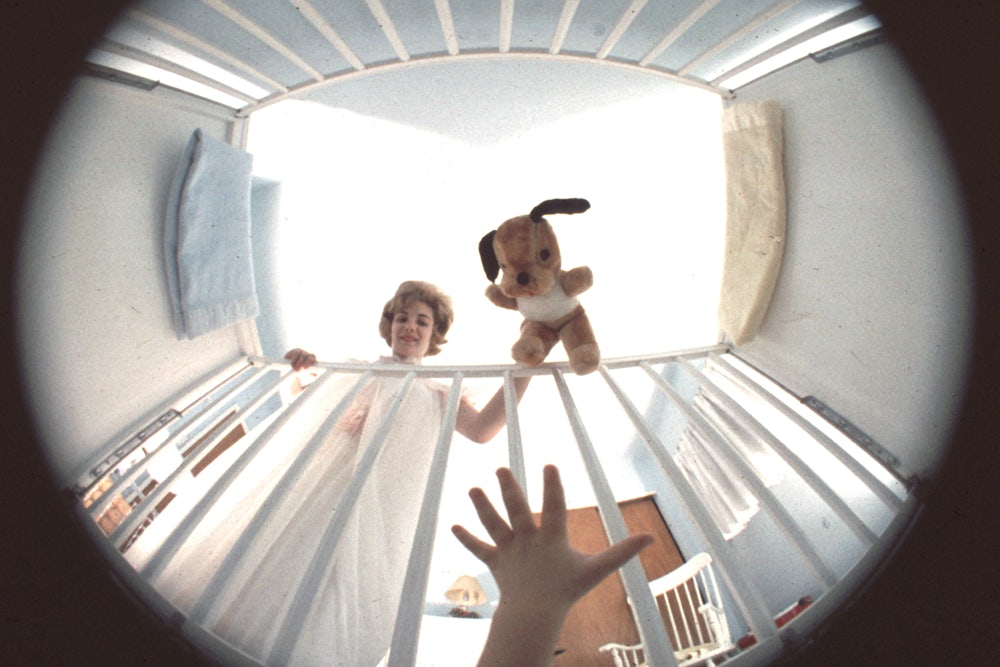

The first few times I left the house without my first child, I forgot that there was no visible sign of my having just given birth. Waddling gingerly down the sidewalk and into the crosswalk and then the convenience store, I expected the deference that my belly had recently commanded. It took me a few blocks to realize that without the baby, I was just a slow-moving, disheveled woman with unsightly stains on her T-shirt.

In her new book The Wilderness, novelist Ayşegül Savaş documents the “messiness and entanglement” of the 40 days after birth, a period so often completely invisible to the outside world, especially in a society of atomized families. The pregnant person is extra visible, then they disappear. It’s a cloistered time, and Savaş’s book is cloistered: an essay in 40 parts, one for each day, but they are not diary entries so much as scenes, memories, or pieces of research, reflections on something she’s read. Number one, for instance, a brief three-paragraph fragment, mentions but doesn’t detail her 24 hours of labor, focusing instead on her mother’s arrival, when “she burst inside and ran toward the baby. What I remember is she didn’t kiss me. She didn’t come to her own child first.”

Her relationship with her mother is the strongest current in the book, stronger than that with the baby, who is barely described; it cries, it is held, it sleeps. The baby is not really anything, just yet. Savaş is waiting “for the baby to reveal itself to me. To know who she is, or what, exactly, she wants.” Savaş’s mother, a pediatrician in Turkey, has come to stay in Paris with her and her husband. Her mother cooks and cleans nonstop, offers pragmatic advice, is good at soothing the baby. They don’t go out or see their friends—they feel too disorganized for visitors. Savaş is in pain and weepy, bothered by nightmares and fearful hallucinations, having trouble breastfeeding and lashing out at her mother for being what she perceives as insufficiently warm toward her.

To understand this unsettled state, she doesn’t go to the science of postpartum depression, the coursing of hormones through the body. She turns to more ancient metaphors, like the Turkish myth of the Scarlet Woman, “a demon in human form who attacked the postpartum mother and baby.” (Turkish women traditionally wear something red during labor to keep her away.) Savaş traces the figure also to Islamic traditions of jinn, and the biblical figure of Lilith, herself possibly derived from the Sumerian epic of Gilgamesh. Ghosts, phantoms, and spirits occupy the insomniac strangeness of those first 40 days. So do texts with other women, “about pumps, about sleep, about the pelvic floor and identity—‘what does it even mean?’—about night sweats and bone broth.” She reads about shamans, about encounters with bears; she reads Deleuze and Guittari. The book’s register shifts wildly too, from chatty conversation to knotty theorems like “the postnatal wild serves as a unique space of chaos untethered from linear history, clashing time frames with great force.”

The “disorder, pain, and loneliness of the early birth story” is also a “common experience, happening everywhere in the world,” Savaş writes, and to understand it she has to turn to lore that isn’t immediately reflected in the conditions of her giving birth in Paris attended by her mother and her helpful husband, informed by intellect and information. Her recent novel, The Anthropologists, was about finding ritual and community and determining the point of life in a deracinated, urban, and cosmopolitan if economically precarious setting. Here, she wonders if the evil-eye bead she hangs on the baby’s diaper basket is anything more than decoration. But she wants to believe that there is something to it. “I am resistant to the urge to explain, to bring clarity to the wilderness,” Savaş writes. And perhaps it has to do with her vocation as a writer: “What is lost, in the direct correspondence of the primitive to modern, of myth to science, is the space of imagination” she says, and also “darkness; the challenge to feel our way without perfect vision.”

Savaş’s new book has received praise as part of “the growing pantheon of postpartum literature”—a terrible term that recalls the stapled sheaf of papers you get upon discharge from the hospital with warnings about hemorrhoids and hemorrhages. But The Wilderness is indeed part of a slew of little books on new motherhood and art (mostly writing), and the tensions and fecundity therein. In the last six years that I’ve spent a lot of time pregnant or lactating myself, I’ve read many of them, and they do start to sound similar. Even if I identify with it, I get a little jaded at the tone of wondrous novelty, the burst of discovery of a basic category of the human condition. The outrage at the many things the new mother does not know, that we were not taught or warned about. The chagrin at our own ignorance, the newfound sympathy for our foremothers.

I catch myself; imagine how many enormous, self-important books we’d be subjected to if men gave birth. Or would we be? The feminized labor of, well, labor, and everything that comes after leads many caretakers to weigh their creative urge against their other duties and find it unearned. Elena Ferrante, one of the mother figures of contemporary motherhood lit, has remarked: “For a long time I hid the fact that I was writing … you’re ashamed of your presumptuousness, because there is nothing that can justify it, not even success.”

All these little books are an answer to a challenge implicit in a section of Rivka Galchen’s Little Labors, the title of which is “Notes on some twentieth century writers.” It begins like this:

Flannery O’Connor: No children.

Eudora Welty: No children. One children’s book.

Hilary Mantel, Janet Frame, Willa Cather, Jane Bowles, Patricia Highsmith, Elizabeth Bishop, Hannah Arendt, Iris Murdoch, Djuna Barnes, Gertrude Stein, Virginia Woolf, Katherine Mansfield, Mavis Gallant, Simone de Beauvoir, Barbara Pym: No children.

And so on (the entries get longer; many of the writers do have children). The books combat the logic of an unnamed famous male author that Heidi Julavits encounters in her parenting memoir Directions to Myself, who says he sees children as books not written. All of them are also an answer to Galchen’s feeling before she had her child that babies are subjects that are “perfectly not interesting.” Can you make a book about them that is?

Some of the recent motherhood books are quirky and humorous (Galchen; Jazmina Barrera’s linea nigra); some of them try to make boringness into a virtue (Kate Zambreno’s The Light Room). They are heavy with quotations, especially of other books in this tradition (especially Adrienne Rich’s Of Woman Born, Rachel Cusk’s A Life’s Work), and some of them bring in other traditions—Turkish folklore in Savaş, Mayan mythology in Barrera, queer theory in Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts. They are often short, or are structured in short bursts, recreating the frequent interruptions of a needy child or the disruptive effects of physical discomfort. In linea nigra, Barrera celebrates this flourishing “of fragmented texts” about “pregnancy, childbirth, and breastfeeding”: “I love this new mode of writing and hope that it will become much more than a fashion … I want there to be more than enough of them, and for them to be good, bad, or indifferent books. I want a canon and a tradition. And also a rupture, counter-canon books. New literary genres.”

One such entrant to the counter-canon comes from Barrera’s partner, the Chilean writer Alejandro Zambra. His new book, Childish Literature, is like the bouncy castle to the hard park bench of so many motherhood memoirs. Some of Childish Literature follows the fragmented essay form. There are reflections on screen time, soccer, and Covid (the overlapping confines of childrearing and quarantine being another recurrent theme in recent books). There is also a poem, and a very sweet short story about two boyhood friends. Zambra is funny, filling his various experiments with deadpan jokes and self-deprecation and scenes that play up the still lowered expectations of a father with a young child. In one essay, he takes a heroic dose of mushrooms for a migraine and ends up trying to imitate the crawling of his infant son while, next door, Barrera is leading a class on infant CPR (you can read another version of this story in her book, in which she comes off as bemused rather than annoyed). True to the general gender segregation of the parenting book (motherhood or fatherhood, and never the two shall meet), there is a lot about his relationship to his own father—touching essays on his own rebellions and their stilted attempts to communicate through the traditional male domains of fishing and sport.

Zambra’s book is unabashedly sentimental: “The truth is,” he writes, “that when it comes to writing about our children, happiness and tenderness defy our old masculine idea of the communicable. What to do, then, with the joyous and necessarily dopey satisfaction of watching a child learn to stand up or say his first words?”

But it takes a very masculine confidence to communicate that level of sentiment. There’s an expectation of anguish in contemporary motherhood—as Atossa Araxia Abrahamian has written, some writers seem to “feel so deeply and personally afflicted by the travails of gender, labor, and reproduction that it becomes difficult to enjoy (or admit to enjoying) the nice bits.” Something about a bubbly book from a new dad can be a bit irksome. Emily Gould called her husband, Keith Gessen, “the Christopher Columbus of mommy-blogging,” during the promo for his book about their son, and Gessen’s sibling Masha Gessen asked, “Where else, in what other period, in what other country … does a person not carry responsibility for another human until they’re completely grown up?” Zambra (who lives in Mexico City, as yet still another country) writes that if he had to sum up his first hundred or so days of parenting, “my telegram would say: I’m having a great time.” A suspiciously good time, a harried mom might think. And yet, I’m glad the book exists.

In every parenting memoir I’ve read, reading offers solace and gives confidence for this new phase of life; the next, inverse step, seems to be to let that life give new confidence to the writing. There’s a line from an essay by Natalia Ginzburg (another staple of motherhood lit) that, for me, encapsulates the literary stakes. After her own period of “exile” after her children were born, she emerges a new writer: “I no longer wanted to write like a man, because I had had children and I thought I knew a great many things about tomato sauce and even if I didn’t put them into my story it helped my vocation that I knew them.”

Motherhood memoirs tend to focus on the tomato sauce, and something is reduced in the simmering. I now find myself wanting to read novels by each of these writers, where the sauce is on the back burner while something else happens in the kitchen—conversation, love, plots, even those involving children. I loved, for instance, Zambra’s novel Chilean Poet, a rare depiction of stepfatherhood. When I read Zambreno, who cites the Japanese novelist Yūko Tsushima, I started thinking maybe I should put down that book and reread her instead. Territory of Light involves the daily work of caring for a toddler. Woman Running in the Mountains has a long section set in a daycare. You could say they are both about babies, but they are about many other things too, and they are perfectly interesting.