“There’s a lot of unemployed philosophers around,” the philosopher told me. “But how many of them want to go work for the military?” I’d reached out to Peter Asaro, who is also a professor of media at the New School and the vice chair of the International Committee for Robot Arms Control, to talk about a new program by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA, that aims to answer a thorny question: How well will autonomous weapons adhere to ethical questions? In its budget request from 2024, DARPA had allotted $5 million to the AI ethics program, known as ASIMOV, with $22 million to follow in 2025.

Practically speaking, what all the money meant was that the Department of Defense was looking to hire philosophers and pay them far more than philosophers usually make. But according to several sources, the contract was split into small, partial awards between multiple applicants—notable winners included the multibillion-dollar weapons contractors RTX (formerly Raytheon; now Raytheon’s parent company) and Lockheed Martin. The unemployed philosophers, it seems, were out of luck again.

“Frankly, it’s kind of an Onion headline,” said one philosopher, who had belonged to a rejected team. “DARPA gives this huge grant to Raytheon to figure out the ethics of AI weapons—Raytheon, the company that’s going to make the AI weapons.” Asaro, who hadn’t applied, was nonplussed. Did it worry him, I asked, that military contractors might decide the ethical terms of engagement for their own weapons?

“I mean, they do anyway,” he said.

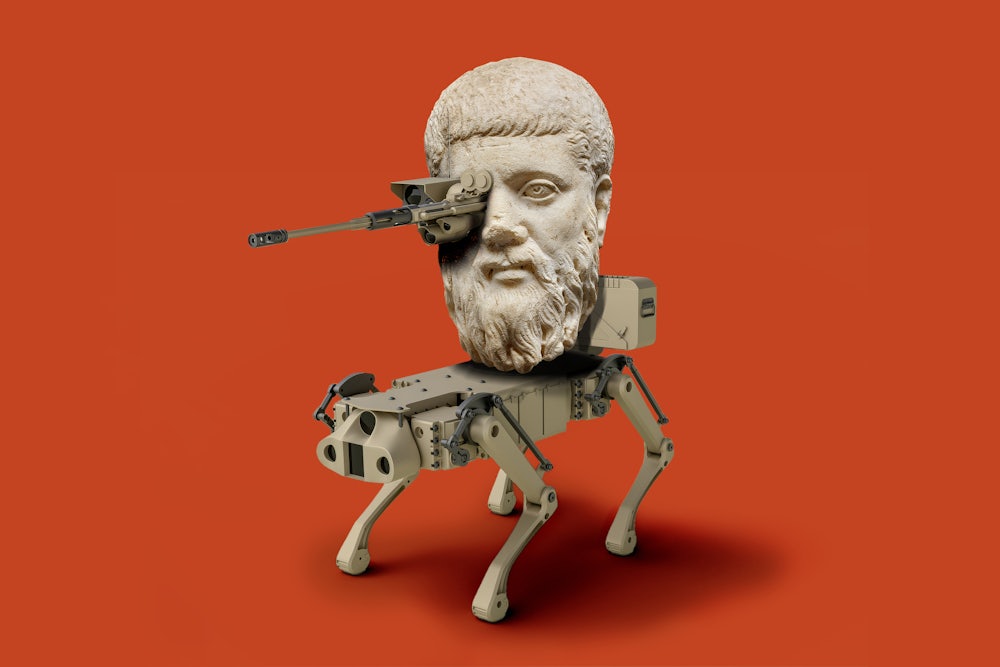

Artificial intelligence as an academic discipline was born in 1956 at a research conference at Dartmouth College, but people have been looking for ways to outsource the difficult work of thinking and decision-making for much longer. Centuries ago, stories circulated of talking, disembodied heads—called “brazen heads”—whose creation was alternately credited to their inventors’ mechanical brilliance or friendly relationship with demons. The Roman poet Virgil was said to have had a brazen head, as were Pope Sylvester II and philosopher Roger Bacon. Some of the heads not only spoke but debated, reasoned, and predicted the future.

The talking heads were the kind of gimmick DARPA would have loved—predictive, creepy, imaginary—but when the agency was founded in 1958, in a panicked attempt to get the Americans into space after the Soviets launched the Sputnik satellite, the idea of outsourcing thinking and decision-making to a nonhuman actor was just as fantastical as when Bacon (allegedly) possessed a brazen head in the thirteenth century. Yet as DARPA became the Defense Department’s moon shot agency, that soon changed. DARPA created the internet, stealth technology, and GPS, and funded research into the efficacy of psychic abilities and the feasibility of using houseplants as spies. As the occult fell out of fashion and technology improved, the agency turned to big data for its predictive needs. One group it worked with was the Synergy Strike Force, led by American civilians who, in 2009, began working out of the Taj Mahal Guest House, a tiki bar in Jalalabad, Afghanistan. United by a love of Burning Man and hacktivism, they were on the country’s border with Pakistan to spread the gospel of open-source data, solar power, and the liberatory potential of the internet. Soon after setting up shop, the group hung a sign in the Taj that read, IF YOU SUPPLY DATA, YOU WILL GET BEER. The data’s offtakers were conveniently elided—they were turning over the information they collected to DARPA, which ultimately used it to predict patterns of insurgency.

The Synergy Strike Force was short-lived: After its Afghan bar manager was shot in the chest in a drive-by attack, the group fled back West. But its legacy lives on in today’s artificial intelligence boom, where the increasingly grim requirements of global empire loom behind techno-utopian promises. Depending on whom you ask, artificial intelligence is either little more than a parlor trick, a precursor to fully automated luxury communism, a weapon of mass destruction, a giant energy suck, or all of the above.

Today, DARPA operates primarily as a grant-making organization. Its core team is fairly small, employing roughly 100 program managers at any given time and operating out of an office on a quiet street in Arlington, Virginia, across from an ice-skating rink. One of DARPA’s former directors estimated that 85 to 90 percent of its projects fail.

Nevertheless, it—and AI—are here to stay. President-elect Donald Trump’s pick to lead the Environmental Protection Agency said one of his priorities would be to “make the US the global leader of A.I.” For his part, Trump has promised that he would revoke a number of Biden administration regulations aimed at controlling the use of artificial intelligence. What’s clear is that artificial intelligence will be unshackled under Trump. It’s hard to imagine it will be ethical. For that matter, can you even teach ethics to a piece of technology with no capacity for doubt?

“That’s kind of the first step in enabling self-reflection or introspection, right?” Peggy Wu, a research scientist at RTX, told me. “Like if it can even recognize, ‘Hey, I could have done something else,’ then it could start doing the next step of reasoning— ‘Should I do this other thing?’... The idea of doubt for us is really more like probability. You have to think about, well, it kind of explodes computationally really quickly.”

ASIMOV stands for Autonomy Standards and Ideals with Military Operational Values, a clunky title intended as an homage to science-fiction writer Isaac ASIMOV, who outlined his famous Three Laws of Robotics in the 1942 short story “Runaround”:

• A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

• A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

• A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Laws.

Today, ASIMOV’s rules feel like an antiquated vision of the future—one in which machines are guided by a set of unifying principles. (The novelist, for what it’s worth, rarely followed his own rules in his fiction.) But a set of unifying principles is what the ASIMOV program seems to be trying to create. Timothy Klausutis, a program manager at DARPA, wasn’t available to speak about the program, as work on ASIMOV was only just beginning. Nevertheless, last winter, the department released a broad agency announcement describing the initiative as an attempt “to create the ethical autonomy lingua franca.... ASIMOV performers will need to develop prototype generative modeling environments to rapidly explore scenario iterations and variability across a spectrum of increasing ethical difficulties. If successful, ASIMOV will build the foundation for defining the benchmark with which future autonomous systems may be gauged.”

The program is loosely modeled on one developed by NASA in the 1970s to test space technology before launches. The idea is to create a system of benchmarks that use the Department of Defense’s five principles of AI ethics to judge current and future technology: In order to pass muster, the technology must be responsible, equitable, traceable, reliable, and governable. It should also be ethical. Employees at the agency are explicitly instructed to “gauge the system’s ability to execute its tasks when initial assumptions are broken or found to be in error.”

Which brings us back to the question of doubt. The philosophical issues at play are fairly obvious. Whose ethics are you using? How were those standards chosen? Individual definitions of moral behavior vary widely, after all, and there’s something faintly ridiculous about the idea of operationalizing ethical standards. Ethical quandaries are ethical quandaries precisely because they are fundamentally painful and difficult to resolve.

“You can use AI iteratively, to practice something over and over, billions of times,” Asaro said. “Ethics doesn’t quite work that way. It isn’t quantitative…. You grow moral character over your lifetime by making occasionally poor decisions and learning from them and making better decisions in the future. It’s not like chess.” Doing the right thing often really sucks—it’s thankless, taxing, and sometimes comes at significant personal cost. How do you teach something like that to a system that doesn’t have an active stake in the world, nothing to lose, and no sense of guilt? And if you could give a weapons system a conscience, wouldn’t it eventually stop obeying orders? The fact that the agency split the contract into smaller, partial awards suggests that its leaders, too, may think the research is a dead end.

“I’m not saying that DARPA thinks that we can capture ethics with a computer,” Rebecca Crootof, a professor at the University of Richmond and a visiting scholar at DARPA, told me. “So much as it would be useful to show more definitively whether or not we can or can’t.”

Everyone I spoke to was heartened to hear that the military was at least considering the question of ethical guidelines for automated tools of war. Human beings do horribly unethical things all the time, many pointed out. “In theory, there’s no reason we wouldn’t be able to program an AI that is far better than human beings at strictly following the Law of Armed Conflict,” which, one applicant told me, guides how participants should engage in armed conflict. While they may be right theoretically, what that looks like at the granular level in a war is not at all clear. In its current state, artificial intelligence mightily struggles with nuance. Even if it improves, foisting off ethical decisions onto a machine remains a somewhat horrifying thought.

“It’s just, like, baffling to me that no one is paying attention to … this input data being used as evidence or intel,” said Jeremy Davis, a philosophy professor at the University of Georgia, who’d also applied for the contract. “What’s frightening is that soldiers are going to be like, ‘Well, I killed this guy because the computer told me to.’” Sixty years ago, social critic Lewis Mumford offered a similar warning against offloading responsibility to technology in his essay “Authoritarian and Democratic Technics,” cautioning that “the bargain we are being asked to ratify takes the form of a magnificent bribe…. Once one opts for the system no further choice remains.”

Mumford understood that the emerging technological regime was frightening not only because it was dangerous or omniscient, but also because it was incompetent, self-important, even absurd.

Last year, while visiting my brother in the Bay Area, we ended up at a launch party for an AI company. Walking into its warehouse office, you could sense the money coursing through the room and the self-importance of the crowd, living on the bleeding edge of technology. But it quickly became clear that the toilets were clogged and there were no plungers in the building. When we left, shit was running through the streets outside.