Growing up in the evangelical church in the piney woods of east Texas, the world felt circumscribed by an ever-present fear—not just of sin but of ideas that might challenge the worldview handed down to those of us in the pews. Everything outside the Christian framework—including secular music, television, and books—was discouraged. Just as I signed multiple purity pledges throughout my preteen and teen years, promising to avoid not just sex but even impure thoughts, we were taught to practice absolute abstinence from dangerous ideas. Not that those dangerous ideas necessarily always came from the annals of great historical thinkers or even figures from the contemporary political climate. As it happens, the most famous of these examples was a widespread prohibition on Harry Potter. To read about witches and wizards, I was told, was to open oneself to the occult and risk spiritual ruin.

This concept of heterodoxy isn’t simply that these works contain themes or ideas counter to Christian teaching; the central belief about ideas is that they are akin to demonic possession, much like the New Testament accounts we heard in Sunday school. This belief—that ideas themselves have a unique, uncontested power to infiltrate and corrupt our minds and souls—reflects the fundamentalist evangelical worldview, one deeply skeptical of intellectual engagement and critical thinking. Rather than the notion that ideas can be critically analyzed and either accepted or rejected, it held that dangerous ideas can indoctrinate and possess you if you are merely exposed to them. To read a book or discuss a theory, in this worldview, is not to exercise one’s intellectual faculties but to risk being overtaken by a seductive, malevolent force with no hope of resistance.

Common in evangelical theology is the concept of spiritual warfare: the idea that Satan and/or other demons are ever-present entities seeking to corrupt and destroy humans—especially the faithful. To resist succumbing to these forces requires constant vigilance and protection through prayer and strict adherence to the evangelical interpretation of biblical teachings. In this worldview, demonic possession or influence mirrors the evangelical concept of ideological corruption; both presume human weakness and vulnerability to external forces that can only be resisted through complete avoidance and submission to religious authority. Just as corrupting forces can enter through seemingly innocuous sources, such as reading, music, or even yoga, dangerous ideas can infiltrate through educational, political, and cultural discourse.

This framework rests on a central belief in human moral weakness that has been present in Christian theology since at least Augustine. For him, humans are naturally depraved and thoroughly corrupted by original sin. If humans are inherently sinful and malleable to any influence, then exposure to challenging ideas—those not central to the evangelical worldview—becomes dangerous. This theology becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy: Because humans are weak and must accept only the orthodoxy of their scriptures or church leaders, they never develop the critical thinking skills that might strengthen their intellectual facilities or their resistance to indoctrination. Christian theology and secular ideas can be, and are, reconciled by many. Despite his somewhat pessimistic view of humanity, even Augustine actually encouraged intellectual engagement and reason. He argued that Christians should study secular knowledge and philosophy, viewing them as tools that could be used in service of understanding divine truth.

Today, through the decades-long marriage of evangelical Christianity and the political right, this intellectual skepticism is no longer confined to the pews. The evangelical distrust of intellectual inquiry has found a powerful ally in American right-wing politics, reshaping the nation’s cultural and educational landscape. The rise of Jerry Falwell Sr.’s Moral Majority and its embrace by the Reagan campaign provided organizational structure to these fears, helping translate religious anxieties about intellectual corruption into political action. Building on the foundation laid during the Reagan administration, figures like Pat Robertson continued to leverage this partnership in the 1990s through organizations like the Christian Coalition of America.

They capitalized on fears of moral decline to mobilize voters and influence policy, solidifying evangelical influence within the Republican Party. This relationship deepened with the rise of culture wars, as issues like banning abortion, putting Christian prayer in schools, and limiting LGBTQ rights became rallying points for evangelical activism. Under George W. Bush, this alliance reached new heights with the establishment of the White House Office of Faith-Based and Community Initiatives, which provided federal funding to religious organizations for social services, and the emphasis on “compassionate conservatism,” which appealed to religious voters while advancing right-wing political goals.

This now firmly established connection between religious conservatives and the political structures of the right have created a feedback loop in which religious fears about moral corruption justify political intervention in education and culture, while political power gives religious leaders unprecedented influence over public institutions (all while they don’t pay taxes to the government). This dynamic reached new and absurd heights during the first Trump administration, when evangelical leaders like Franklin Graham and Paula White portrayed Trump as a divinely appointed leader against secular corruption and defender of Christian values, despite his well-known history of flamboyantly immoral personal conduct. The movement’s willingness to embrace such a morally compromised figure reveals that the real priority of the Christian right has always been the accrual and maintenance of its own political power and influence over the control of policy, information, and ideas—not moral virtue or devotion to God.

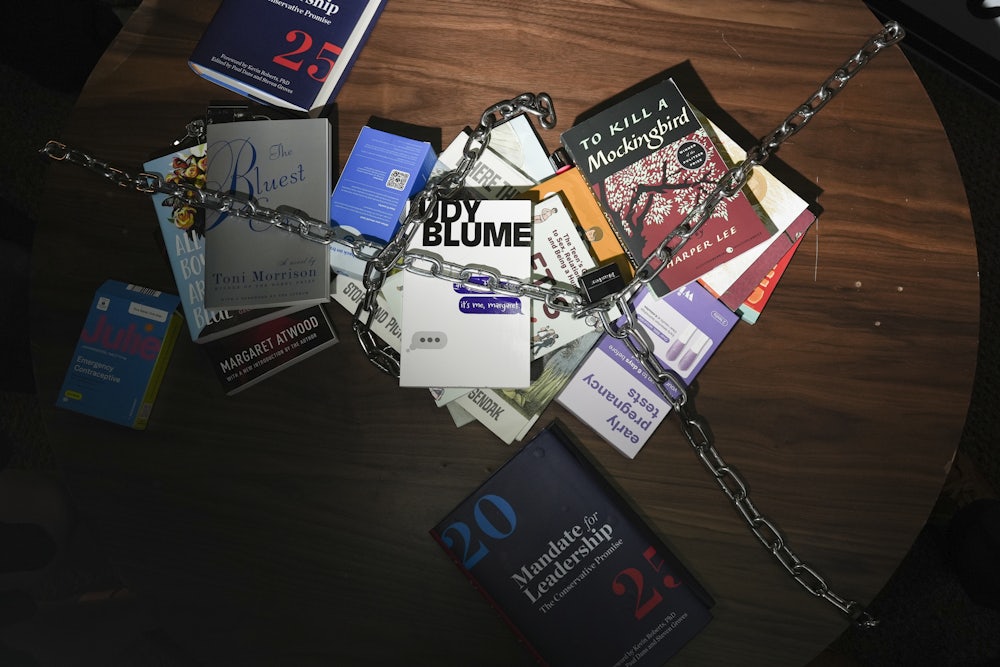

The alliance between evangelical Christianity and conservative politics has fostered a cultural paranoia that seeks to limit the range of acceptable ideas. Today, we see this legacy in mounting campaigns against public education. According to PEN America, documented book banning attempts in American schools rose by 33 percent in 2022–2023 and an incredible 197 percent in the 2023–2024 school year, with over 4,000 titles targeted. This wave of censorship disproportionately targets books by or about people of color and LGBTQ individuals, with 40 percent of banned titles explicitly addressing these themes.

These contemporary battles over education echo historical patterns of evangelical anti-intellectualism. During the Scopes Monkey Trial of 1925, fundamentalist Christians fought to prevent the teaching of evolution in schools (a cause I now cringe to remember I took up in my eighth grade science classroom 80 years later, when I was still adhering to the church dogma). This battle established a template for future conflicts: Frame scientific or social progress as a threat to religious values, position schools as battlegrounds for cultural warfare, and assert parental and religious authority over educational content. Today’s campaigns against “critical race theory” and LGBTQ inclusion follow this same playbook, treating these ideas not as subjects for discussion and analysis but as dangerous forces that must be exorcised.

The coordinated efforts to ban books addressing racism, LGBTQ identities, and systemic inequality frame these ideas as corrosive forces capable of undermining young minds. They have co-opted the language of inappropriateness that Tipper Gore once applied to explicit lyrics in rock and rap, the better to use it as a smokescreen for creating a white supremacist, heteronormative curriculum. Similarly, the rhetoric surrounding “cultural Marxism”—a decades-old McCarthyesque conspiracy theory revived to stoke fears of leftist infiltration, which has its roots in the antisemitic Nazi campaign against “cultural Bolshevism”—posits that schools, universities, and media are indoctrinating an unsuspecting populace with Communist ideas.

It is no coincidence that these are precisely the places where many of us learn to think critically and examine ideas for ourselves. While the idea that colleges are indoctrinating students is an unfounded—and for those of us who are in higher education, comically absurd—notion, what higher education can do is encourage students to develop a whole range of intellectual skills and to question their own beliefs and biases to develop a better understanding of the world and forge their own values. That is why higher education is in the crosshairs of the Christian right. But this belief manifests itself beyond book bans and allegations of collegiate indoctrination to the vilification of diversity, equity, and inclusion intiatives, woke education, and campaigns to seize control of school boards.

The effort to control school curricula—whether by banning Maia Kobabe’s Gender Queer or opposing teachings on systemic racism—is part of a broader project to sanitize history and obscure systemic injustices. By labeling these narratives as dangerous or un-American, right-wing activists effectively demonize the act of questioning political power, as if it were another Christian god. This conflation of political and religious authority is particularly dangerous in the context of rising authoritarian movements. When political leaders can frame dissent as not just politically incorrect but spiritually corrupting, they create a powerful tool for suppressing opposition. The January 6 insurrection, in which Christian symbols and prayers mixed freely with political violence, demonstrated how thoroughly this fusion of religious and political authority has penetrated American conservatism.

This movement’s profound fear of intellectual engagement reveals a deep insecurity about its own beliefs—after all, truly robust ideas don’t require such elaborate protection—and, in fact, a profound respect for the power of ideas. You don’t construct elaborate systems of thought prevention unless you believe, on some level, that exposure to new, better ideas really could transform society.

Treating ideas as possessing forces rather than subjects for critical examination actually makes people more vulnerable to manipulation, not less. When we don’t develop the skills to critically evaluate ideas—to question, analyze, and assess them—we become more susceptible to actual religious and political indoctrination and groupthink. When we frame certain thoughts as too dangerous to encounter, we create the conditions for authoritarian control.

After all, if ideas can possess us like demons, then we need authorities to protect us from exposure; a role eagerly filled by those seeking to consolidate power through censorship and educational control. The antidote to this authoritarian impulse is a renewed commitment to critical thinking, intellectual freedom, and pluralism. It is a belief in the transformative power of education and the resilience of individuals to engage with complex, even uncomfortable truths without being possessed by them.

In an era of rising authoritarianism and deepening social division, our capacity to think critically about ideas rather than fear them may well determine whether democracy survives. The question isn’t whether we can protect ourselves from ideas, but whether we can develop the intellectual resources to evaluate ideas thoughtfully.

The possession model of ideas, with its roots in evangelical theology and its branches in contemporary politics, represents more than just a religious or educational philosophy—it is fundamentally undemocratic, replacing the ideal of an informed citizenry capable of responsibly wielding individual rights and freedoms with an infantilized vision of humanity where everyone must be under constant supervision at the hands of autocratic strongmen. Democracy requires belief, not in our invulnerability to ideas or to our infallibility, but in our capacity to engage critically in our cultural and political conversation. The most dangerous idea of all is that we must be protected from the act of questioning, thus surrendering to those who would think and act for us.