If Hillary Clinton’s 2016 loss was a shock, Kamala Harris’s defeat was a gut punch of near-fatal proportions, politically and emotionally. Donald Trump’s win eight years ago could quickly be written off as a blip. It wasn’t (just) that Hillary was a woman; it’s that she was Hillary, the argument-slash-rationalization went. As the former first lady, she didn’t really represent change for a public growing increasingly frustrated with dysfunctional Washington. She wasn’t “likable,” a slam more commonly wielded at women, but not only at women. And Trump’s brand, for many Americans, was exactly as he had marketed it, even if it wasn’t real: He was seen by just enough voters as a brilliant businessman and negotiator, a wealthy playboy who nonetheless spoke for the common man, and a political outsider who could shake up the Washington establishment.

And after all, Clinton was the first female major party nominee the country had considered. Surely, that would get American voters used to the idea of a female president and pave the way for the next woman to make it to the general election. And in 2024, Democrats had more ammo. Trump’s true colors had been exposed on the national and world stages and in the courtroom. His adolescent insults of the 2016 campaign had escalated as he made crude remarks about women in general and female candidates in particular. Women were literally dying, waiting for care, after a Supreme Court made up of one-third Trump appointees took away the guaranteed right to an abortion. Trump had the ignominious distinction of being the first convicted felon to become a major party nominee for president. Americans knew what Trump was about in 2024—and they voted for him anyway, and in larger numbers. So much for the Hillary-specific blip.

Distraught Democrats have been asking the predictable but necessary questions. What did we do wrong? Was it our message, or our messaging methods? Or—perhaps most dispiriting—did we do everything right, with a great candidate, but it doesn’t matter because Americans simply won’t put a woman in charge of the country?

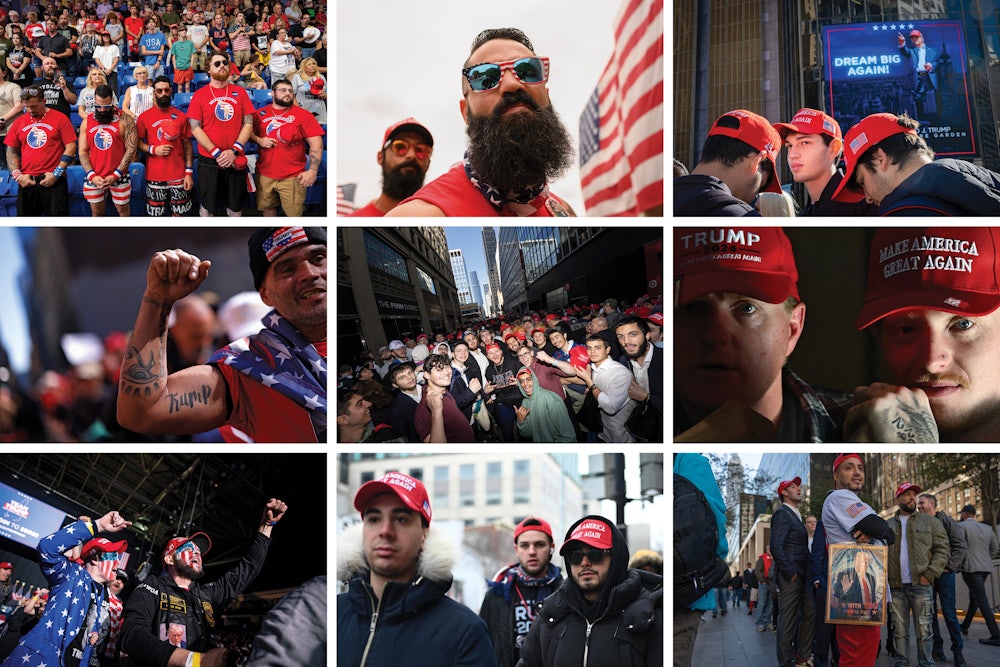

The answer, political and sociological analysts agree, is that gender indeed mattered in the election, arguably enough to tip the scales to Trump. But it is so much more nuanced than the simple matter of Harris’s gender (though surely there were voters who could not, or would not, pull the lever for a female president). Much of it had to do with young men, a group experts say is adrift—lonely, faced with competing pressures to be tough and to share their emotions, and struggling with what it means to be a man in a world where gender roles are changing rapidly and the very notion of gender itself is being challenged. But as a longtime privileged group, men are typically not on the Democratic Party’s list of aggrieved voter groups looking for government to protect them from discrimination or other harm.

It’s the “Democrats’ blind spot,” said Aaron Smith, co-founder of the Young Men Research Initiative, echoing complaints from those within the party who say the Democrats were so focused on mobilizing women voters that they ignored men. Take a look at the Democratic National Committee’s website, Smith said. It has a section called “who we serve,” and it starts with the pledge, “Democrats are the party of inclusion. We know that diversity is not our problem—it is our promise. As Democrats, we respect differences of perspective and belief, and pledge to work together to move this country forward, even when we disagree ... we do not merely seek common ground—we strive to reach higher ground.”

After that, readers can click on 16 different categories of people the party serves—everyone from women to union members and seniors to LGBTQ people. “There’s nothing, no mention of men, period,” Smith said. That neglect, he argues, hurt the party.

In polling the institute has done, “many young men, even young men who said ultimately they would vote for Kamala Harris, thought the Republican Party and Donald Trump were more in favor of them,” Smith said. “That has long-lasting political implications, if that gets into the heads of young men as they get older, and start voting in higher numbers.”

David Hogg, the teen gun safety champion turned Democratic activist, described a startling pushback he got from fellow Democratic fundraisers at a question-and-answer session during the 2024 Harris campaign. “What are we doing about young male voters?” he recalled asking. “The amount of vitriol and backlash I got—that it was such a dumb question—was telling,” said the 24-year-old Hogg, who mounted a successful race for vice chair of the DNC on a platform of winning back young voters. There’s a tendency for liberals in general and Democrats in particular to focus on groups that have suffered from cultural and legal restrictions on opportunity, many Democrats acknowledge, and the default assumption is that men—who have largely owned and run the world for millennia—don’t need special attention. But “as a party, we need to stop acting as though empathy is a zero-sum game,” Hogg said.

Strategy has consequences. Pundits were expecting a historic gender gap in 2024, one driven by the Dobbs abortion ruling, fueled by the historic presence of a Black and Asian female heading the ticket, and ending in a Harris win. That didn’t happen. Harris got 53 percent of the female vote, substantially less than the 57 percent earned in 2020 by President Joe Biden, the man hounded from the 2024 race by fellow Democrats who feared he was a certain loser. Trump won 55 percent of the male vote, more than the 53 percent he got in 2020 when he lost to Biden. Women did turn out a bit more in 2024, making up 53 percent of the electorate as opposed to 52 percent in 2020 (although exit polls aren’t so precise that we should read all that much into a 1 percentage point difference). But it wasn’t enough to secure a win in any battleground state or in the popular vote.

“There was a lot of hype ahead of this election about the women’s vote, that there was going to be a 30- to 40-point gender gap,” said Debbie Walsh, director of the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University. Instead, there was “the same gender gap we’ve been seeing historically since 1980,” one rooted in the basic political trend of women favoring Democrats and men preferring Republicans. All of Harris’s relentless focus on reproductive rights—an issue that proved potent in the 2022 midterms—didn’t turn out to be the deal-closer the Democrats had hoped for. And, as CAWP’s research has shown, “the gender of the candidate is not what drives the gender gap,” Walsh added. “That’s one of the things that got muddled in this election. People just thought it’s going to be through the roof [for Harris] because she’s a woman.”

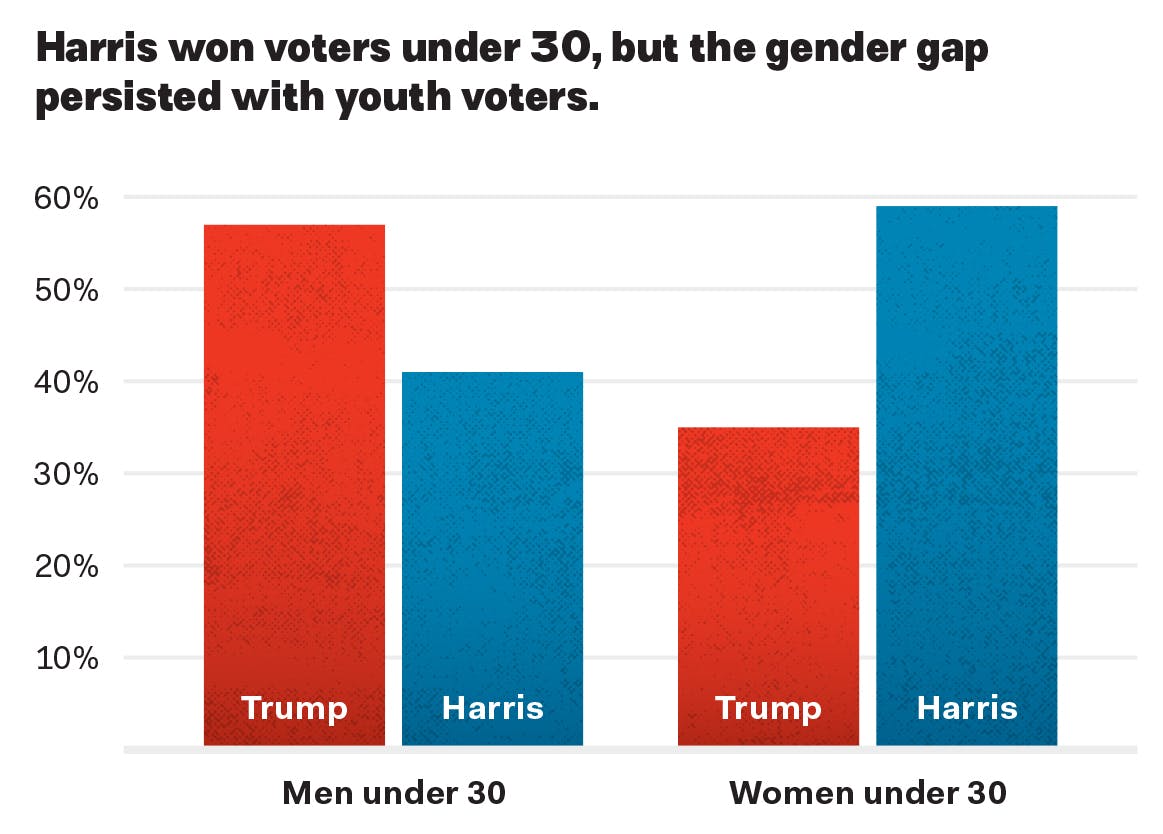

Where there was an enormous gender gap was among young voters. While Harris won voters under 30, according to a Navigator Research poll taken after the election, there was a massive divergence when it came to young men and young women. Males under 30 favored Trump by 16 percentage points (57 percent to 41 percent), while women under 30 went big for the Democrat: 59 percent of women under 30 voted for Harris, while just 35 percent of young women cast ballots for Trump. Those were the kinds of numbers some analysts thought might happen with the overall electorate (and had that happened, Harris almost certainly would have won). But the lopsided young male support for Trump was devastating for Harris, weakening her numbers overall.

It’s not a natural thing, for Democrats, to ask themselves the question: How did we lose men? In the slicing-and-dicing of voter blocs, men, especially white men, tend to be considered the control group. There’s something inherently insulting about that to women; do only women vote with their reproductive organs in mind, while men make more reasoned and nuanced decisions? Do only people of color march into a polling station, thinking about how their race or ethnicity should drive their votes? But at the same time, there has also, arguably, been a tendency to dismiss men (especially white, middle-aged men) as decreasingly relevant to the Democratic equation. With America poised to become a majority-minority nation by 2045, according to Census Bureau projections—and women, who make up just a bit more of the population than men, on a steady path of reliably voting Democratic—the future world was a Democratic oyster. Who needed to listen to men?

Republicans saw those numbers, too, and released a self-performed political autopsy in 2013, trying to figure out how they lost twice to Barack Obama. The conclusion was that the GOP needed to be more inclusive, listening more to people of color, women, and gay and lesbian folks. A smart and deeply detailed 2015 analysis, “States of Change,” completed by senior researchers at the Brookings Institution, the American Enterprise Institute, and the Center for American Progress, came to similar conclusions ahead of the 2016 election. Given the changing face of the American electorate, including race, ethnicity, education levels, and the like, Democrats had a “demographic thumb on the scales in the short term,” the report found. Republicans could still win in 2016 with a near-perfect storm on turnout trends and slight shifts in support among various groups (which indeed happened), but the GOP’s future was going to rely on adapting to America’s new demographic reality.

Trump in 2024 took a characteristically oppositional approach, doubling down on his appeal to men and almost gleefully upping the insults to women, transitioning from the 2016 attacks on women’s looks (“fat pig,” “horseface”) to questioning female lawmakers’ ability to reason or rule (“crazy,” “dummy”) and women’s ability to take care of themselves (“whether women like it or not, I’m going to protect them”). And it seemed a bizarre strategy, if it was a strategy at all; but it worked. While Democrats were tending to their 16 categories of historically underserved or underrepresented groups, Trump went after the voters Democrats had figured didn’t need anyone’s help.

“What the Republicans did at the national level was the exact opposite” of what the Republican 2013 autopsy had recommended, said Ange-Marie Hancock, executive director of Ohio State University’s Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity. “In many ways, it made a kind of rational sense. They made a strategic decision … that they could not become Democrats light without just continuing to lose elections. They decided to completely zag when everybody thought they would zig.” William Frey, the Brookings Institution demographer who was one of the authors of “States of Change,” throws the Democratic Party stereotype back at the GOP: “I would say Republicans are playing identity politics,” Frey said. And for the Republicans, that was successful—to some extent among Black men, a group among which Trump peeled away support; to a greater extent among Latino men; and maybe to greatest extent of all among young men of all racial and ethnic groups.

“The brand of the [Democratic] Party is really bad” for young men, who felt cast aside while the party went whole hog on abortion rights and other issues that did not address the struggles twentysomething men are experiencing, said Victor Shi, a recent college graduate who served as youth engagement coordinator for the Harris campaign. That’s where “young people, young men especially, feel turned off. They don’t feel like they’re part of that. As young men report being lonely and more alienated, all that contributes more to their sense of isolation from the Democratic Party.… We may have spent too much time telling people how important reproductive rights were instead of actually listening to people.”

While Democrats were busily reminding women, people of color, and other parts of their base about the dangers of another Trump presidency, Trump was tapping into the anger and vulnerabilities of young men. Here was a group that statistically, at least, is falling behind women in alarming ways. Seven out of 10 high school valedictorians are girls. Females are dominating college enrollments, and the gap is projected to grow steadily. Women already earn more master’s degrees and doctorates, and that disparity is expected to widen. There appears to be an ambition divide, as well. More women who didn’t complete college said they either couldn’t afford it or needed to work to help support family, a Pew Research Center study found, whereas more men who didn’t go said they just didn’t want to.

Isolation from the pandemic—and exacerbated, experts believe, by social media—adds to a mental health crisis among young men. Men overall make up almost half the population, but 80 percent of the suicides. And young men were a bigger part of the picture during that period: In 2021, men aged 20 to 29 had the highest suicide rate among men, a trend that began in 2018. Before that, middle-aged men were more likely to take their own lives. (In 2022, the suicide rate for men 20 to 29 decreased, while that among middle-aged men increased.) Social stigmas against men seeking help for mental health issues mean lower diagnoses and treatment.

Young men are more likely to be alone as well. A 2023 Pew Research Center study found that 63 percent of men under 30 reported being single (meaning not married or in a committed romantic relationship). Thirty-four percent of women that age described themselves as single. Meanwhile, attention to trans rights (notably mentioned more by Trump than Harris during the campaign) was touching a nerve in young men. Already defensive over the word “toxic” attached to masculinity, young men now wondered what it meant to be a man, and what their place was in a world where gender itself was being discussed as more of a concept than a firm biological state.

Randy Flood, a therapist and co-founder of the Men’s Resource Center of West Michigan, helps men navigate this new world, embracing a new definition of masculinity that is about humanity rather than the locker-room mentality that defines toxic masculinity. In a world where young men are told to be tough (but are also castigated for being too aggressive) and told to express their feelings (but not so much that they look feminine, a term that reads as weak with many men), they are confused, he said: “There’s not a lot of really concrete images of what it means to be a man. We haven’t presented an alternative that really has resonated for young men.” And Trump, Flood said, went right for the soft underbelly of young men’s confusion, insecurity, and anxiety.

“They hear a lot of important truths about how destructive patriarchy” has been, Flood said, but also may sense an “open season” on them by society at large. “We [need] to deconstruct patriarchy. But I think young men come into consciousness, come into the conversations, and they see themselves as being inherently bad and flawed and dangerous. Donald Trump provides them with an alternative.”

Trump ridiculed trans rights, feeding a young male fear that young women were not just surpassing them, but perhaps trying to become them (a strategy that had the ancillary effect of appealing to mothers and fathers worried about their daughters’ bathrooms and locker rooms being invaded by trans women). His misogynistic rhetoric had an old-fashioned quality that ended up appealing to a new generation: You have a birthright to be in charge, to objectify women, to be head of the household, with a wife at home as full-time housekeeper and child-rearer. It was a simple, appealing answer to a generation of men with a lot of questions about what it meant to be a man. Majorities of young men rated Trump favorably ahead of the election, the Navigator poll found. And Elon Musk, the embodiment of tech-bro success, was “liked” by 68 percent of 18- to 29-year-old men surveyed by the Young Men Research Initiative—among the top three of influencers polled.

And Trump knew exactly where to deliver his message. He had uber-macho figures like pro wrestler Hulk Hogan and Ultimate Fighting Championship president Dana White speak at the Republican National Convention. He went on The Joe Rogan Experience podcast and other outlets directed at young men. While Harris courted viewers on TikTok (more popular with young females in the United States), Trump employed YouTube, more favored by men. Republicans outspent Democrats 10-to-one when it came to ads targeting young men, Smith said.

Republicans also did a better job harnessing gaming platforms, an especially rewarding messaging vehicle after the pandemic, when young men turned to gaming during the isolation, Shi noted. “Republicans were able to latch onto it more effectively than Democrats,” Shi said. “They were able to make young men feel more included.”

Democrats weren’t making a special pitch to men, and there are some defensible reasons for that. Decades after the Equal Pay Act and the establishment of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, women still typically earn 82 cents for every dollar earned by men—about the same as in 2002, when women earned an average of 80 cents to the male dollar. And while there’s often an assumption that women are unfairly penalized for spending time away from the paid workforce to raise children, that argument doesn’t entirely explain the gap. According to a Wall Street Journal analysis of recent college graduates—including those who got the same degree at the same top-tier school—male graduates’ median earnings still topped that of their female classmates by 10 percent or more.

The advantage in the diploma divide isn’t resulting in the big jobs for women either. Any female professional advance seems to come with a cruel joke attached to it. In 2023, 10 new female CEOs joined companies in the S&P 500 Index, making that year the first time in history that women CEOs outnumbered CEOs with the first name “John.” The 2023 movie Barbie (despite its superficially tween-girl appeal) was an anthem to female power and autonomy. Margot Robbie, who played the film’s eponymous heroine, along with director Greta Gerwig, were snubbed by the Oscars, while Ryan Gosling, who played the clueless Ken, was nominated for best supporting actor—literally, the plot of the film.

More than a half-century after the passage of Title IX, which gave girls and women more opportunity in school sports, female professional athletes still earn a small fraction, on average, of their male counterparts. And when it comes to control over their own bodies, women have seen not meager progress, but retrenchment, with the national right to abortion taken away and the possibility of prosecution for terminating a pregnancy a threat in some states.

The closeness of the 2024 campaign was just another familiar insult to women—especially Democratic women, who had endured a career of seeing less-qualified men get the better jobs and opportunities and salaries. Here was Trump, a convicted felon, adjudicated sexual abuser, and master teller of falsehoods. And Harris was neck-and-neck with him in the polls—even as Trump escalated his gender-based attacks on Harris and other women who crossed him. “This country has a hard time respecting women. That’s a problem; we can’t deny that,” said Delmarie Cobb, a Democratic strategist who worked as Hillary Clinton’s Illinois press secretary in 2015. Other countries have elected women to lead them; heavily Roman Catholic Mexico, Cobb noted, just elected as president a woman who is not only Jewish, but the daughter of immigrants from Lithuania and Bulgaria. The United States still couldn’t do it, even when the woman’s opponent was a convicted criminal.

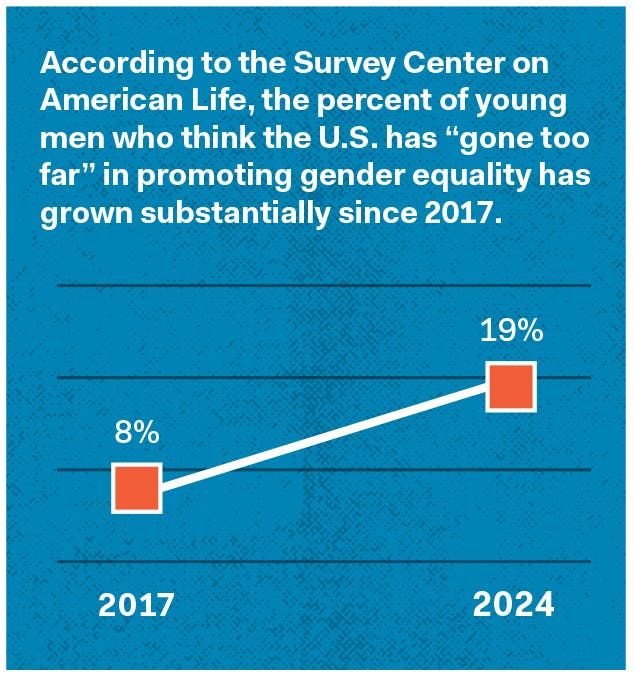

Harris’s gender may not have been the definitive factor in her loss, but young men are less sympathetic to feminism than that age cohort once was. The Survey Center on American Life, a center-right polling project affiliated with the American Enterprise Institute, found that 19 percent of 18- to 29-year-old men felt that the United States had “gone too far” in promoting gender equality—up from 8 percent who felt that way in 2017. Anti-feminist voices from the manosphere—such as Andrew Tate and the Proud Boys—were cited as trusted sources by 46 percent of men ages 18 to 23 and 44 percent of men 24 to 29, in a 2023 study by Equimundo. The same survey found that the youngest men—ages 18 to 23—were the least likely among age groups to say feminism had made America a better place.

Such numbers can be infuriating to those who have fought for many decades to empower women. The temptation is there to say, effectively, to young men: Your gender has had inherent advantages for forever. Women have been held back by law and culture. Any barriers you have now are your own making. Stop smoking dope and playing online games in your parents’ basement and get your act together. Democrats didn’t go that obviously self-destructive route, but they didn’t help themselves with young men either. The Harris campaign spent so much time hammering away on reproductive rights and appearing on media channels directed at women, the campaign message became a version of what young men perceived women in general were telling them: We don’t need you.

Trump proved that Democrats indeed need men. And it’s not a single-election problem; if now-young men get into a habit of voting Republican (as young men did during the Reagan revolution), Democrats will have a harder time, each election, persuading that generation to jump ship as they age. But how can Democrats woo male voters—young men in particular—without abandoning their mission of protecting and defending historically underrepresented groups?

First is acknowledging that young men now are one of those groups in need of help and attention, both for their own sake and for society at large, strategists say. “We have a real crisis in our country, about what young men are going through,” David Hogg said, and the consequences can be devastating, not just for the men’s individual health and advancement, but in preventing tragic outcomes. The lonely and alienated young man, after all, is a prototype for a mass shooter—a type Hogg, tragically, knows all too well. Just as the party talks about the health crisis women are in because of the loss of reproductive rights, Democrats need to be talking, too, about the growing suicide rate, especially among young men, Hogg said. Women got all kinds of attention in the media and by activists when they were remaking (and often) rejecting gender roles during the second wave of feminism and beyond. Men may need similar guidance now.

“This is so much more than politics. Even more than politics, it’s cultural.… We need to explore more ways of showing what it means to be a modern man,” Hogg said. With the move away from the industrial economy and other changes in the world, “the archetypes we have for men, in literature and movies, are increasingly out of date with what it means to be a man.”

When it comes to the Democratic Party’s role, “just showing up and listening” to young men would help, Victor Shi added. “So much of what happened in this election … it seemed like they were telling young men what to believe,” he said. “We know they are struggling. Acknowledging that struggle is really important.”

Second is realizing that young men need political attention as well—and reminding them, without liberal apology, of what the party has done and can do for young males. That means talking more about job creation, for example, or providing training for work that doesn’t require a college degree. Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro, for example, has already removed the college degree requirement for roughly 65,000 state jobs—92 percent of state civil service posts—and made sure that young men got the message. Many surveys, including the gold standard of young voter polls, the Harvard Institute of Politics biennial youth poll, consistently show that young males are drawn to Democratic ideas—just not necessarily to the Democratic candidates. That at least gives Democrats an opening to get back young men, analysts say, if they hone their message and market it specifically and unapologetically to that voter group.

“I think that Democrats for the last 15 years or so have sort of relied on being able to turn out folks we thought were our base. To a large degree, that’s women, especially after Dobbs,” said Shauna Daly, a political consultant who focuses on young men and politics. “We sort of forgot some of this muscle memory about needing to persuade voters. Democrats need to learn how to talk about and to men … how [their] policies specifically benefit men. We haven’t really had that language, haven’t tried to use that language about appealing to men.”

Perhaps the most important part of the puzzle is the method of communication itself. For all the postelection hand-wringing over whether Harris should have done Rogan’s podcast (she didn’t pass on it, Rogan said; she just wanted him to come to her and would do just an hour, a proposal he said didn’t work for him), the messaging problem was about more than just one male-centric podcast. Democrats, argued strategist Jesse Ferguson, need to recognize that the old-style way of communicating with young male voters not only doesn’t reach them—it actively turns them off.

“Young voters, especially young male voters, are getting their information in ways that are dramatically different than the ways Democrats have communicated for the last 10 or more years,” said Ferguson, who was Clinton’s deputy press secretary during her 2016 run. “It’s not just an abandonment of the mainstream media, but it’s a reliance on personality-based messengers—whether they’re on YouTube or on podcasts. And it’s an interest in messengers that aren’t focused on politics.” Trump, of course, is a personality-based messenger in his own right, making his campaign a natural fit for young male voters more attracted to the messenger than policy papers.

“If you think the political system has failed you, the solution is not to provide more messages in media about politics. It’s like, ‘Here, this food tastes bad. Have some more.’ That ain’t going to work,” Ferguson said. Harris indeed used alternative media platforms (like Alexandra Cooper’s Call Her Daddy podcast), but it wasn’t enough. And it wasn’t enough alternative media directed at young men, strategists say.

Going on Rogan wouldn’t have fixed it, but Harris, who had little time to build a campaign after Biden’s summertime departure from the race, needed something like it, Ferguson said. “People need to be willing to sit for an hour-long conversation and engage, and show people who they are. If Democrats want to win back the young voters that we’ve lost, we’ve got to do the modern-day version of playing the saxophone on Arsenio Hall,” Ferguson said, referring to Bill Clinton’s 1992 musical performance on the late-night talk show.

Young men may feel lost. But they are not lost to the Democratic Party, its more optimistic operatives believe—as long as the party focuses its message more effectively and finds a better way to communicate it. “These defeats can be clarifying. Some of the best learning I’ve done politically is being on the wrong side of the outcome,” said Joel Payne, a Democratic strategist who worked on Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign. After all, Harris won nearly nine million more votes than Clinton did eight years previous. “The wrong lesson to take from the last election would be some kind of broad statement about the ability of women to win national elections,” Payne said. Next time, however, they’re going to need men to make it happen.