Brian Pannebecker first drew Donald Trump’s fond gaze by wearing tight T-shirts to Trump rallies around the Detroit area. The shirt displayed the words Auto Workers For Trump, even though the United Auto Workers union didn’t endorse the Republican candidate. “I didn’t know who he was,” Trump said of Pannebecker at a rally in Warren, Michigan, right before he won the 2024 election over the Democrat, Kamala Harris. “All I know is he has very good, strong arms. I’m impressed by his arms. He’s a strong guy.”

Pannebecker, 65, wears a mustache that droops down each side of his chin in the style of Hulk Hogan, the Trump buff who made his name in pro wrestling. Before retiring, Pannebecker drove a forklift at a Ford plant. He became Trump’s unofficial Michigan mascot, stroking Trump’s ego with groupie-like praise while stoking resentment among the MAGA crowd. Later at the rally in Warren, a city in crucial Macomb County, Pannebecker denounced electric vehicles that could replace gasoline-powered cars and pickup trucks, warning that they would underserve the needs of consumers like himself on the drive from the Detroit area to the northwest Lower Peninsula, a year-round vacation and recreation destination near Lake Michigan where many downstate Michiganders have second homes.

“We don’t want to drive those things,” he said. “How do you pull a trailer with four snowmobiles on it up to Traverse City when it’s five degrees below zero in an EV? You can’t do it.”

It isn’t surprising that people like Pannebecker—retired suburbanites for whom hauling around four snowmobiles is the definition of freedom—should have voted for Trump. But last November, they were joined by a more eye-catching roster of Michigan voters who either took a flyer on Trump or just didn’t vote, costing Kamala Harris this state’s vital 15 electoral votes. Trump got 2,816,636 votes to Harris’s 2,736,533, for a victory margin of 1.4 percent (another 109,335 Michigan voters chose minor-party candidates). It was only the second time in the last nine presidential elections, going back to 1992, that the Democrat failed to carry Michigan (Hillary Clinton in 2016 was the other one).

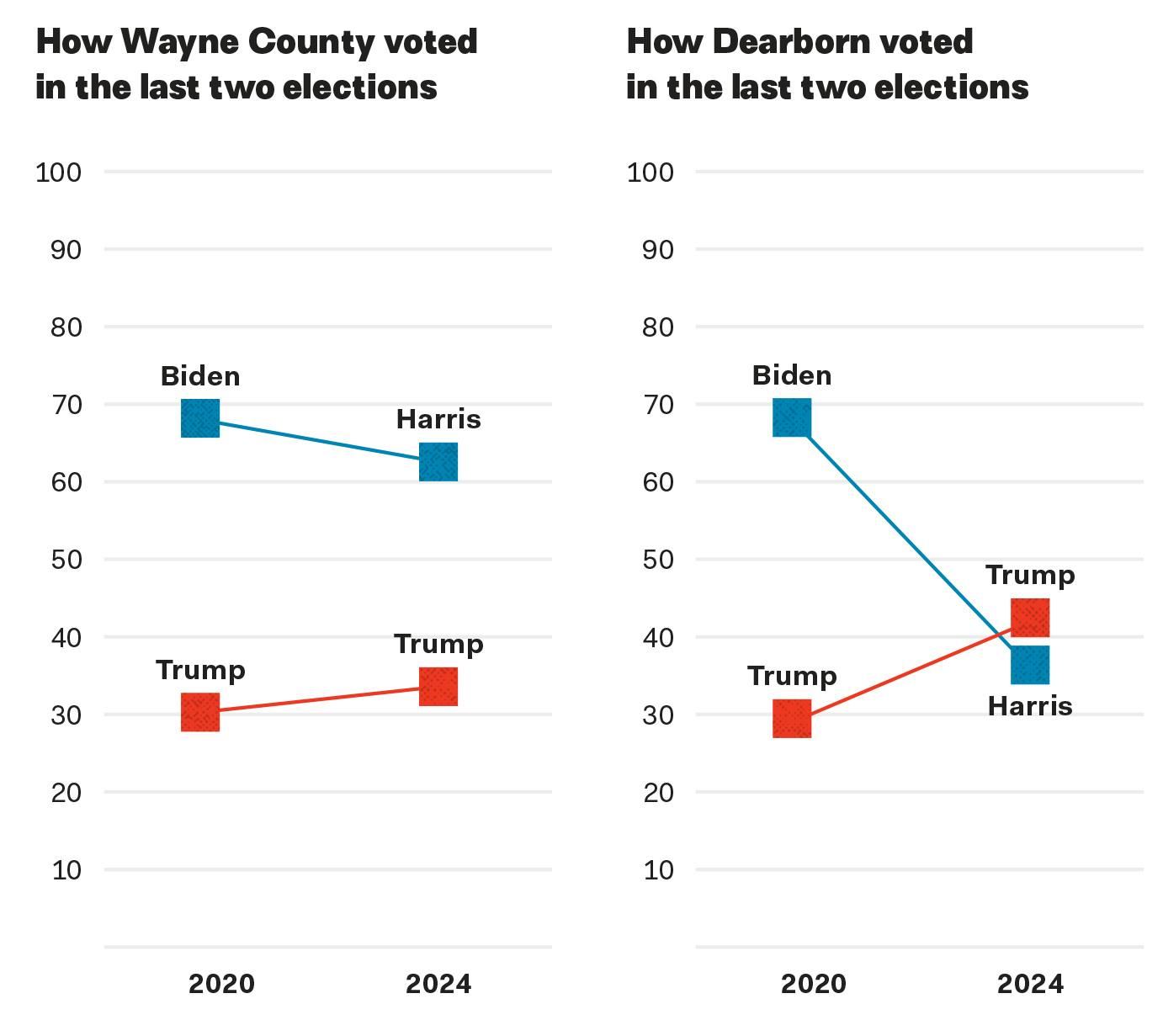

This change was nowhere more apparent than in Wayne County, home to Detroit and still the state’s most populous county. Consider: In most counties, blue and red alike, Harris’s numbers weren’t very different from Joe Biden’s in 2020. In Kent County, home to Grand Rapids, Harris actually outperformed Biden by around 5,000 votes. In Washtenaw, home to Ann Arbor, she got a few more votes than Biden. Likewise in Kalamazoo County, where she did a little better than Biden. She won those counties. But even in the deep-red counties she lost, she generally did no worse than Biden had: In rural counties ranging across the state, like Sanilac, Presque Isle, Luce, and Cheboygan, she got about the same number of votes that Biden had.

The differences were somewhat bigger in the two key counties outside Wayne. In Democratic Oakland County, Harris beat Trump but got about 15,000 fewer votes than Biden. In Republican Macomb County, Harris got about 9,000 fewer votes than Biden had. But even those numbers don’t compare to Wayne, where Harris had a whopping 60,138 fewer votes than Biden had. Trump also upped his total in the county from 264,553 in 2020 to 288,860 last November—an increase of 24,307.

Those two figures, Harris’s decline in Wayne County and Trump’s improvement there since 2020, add up to 84,445. Trump won the state by 80,103. Allowing for some overlap between Harris’s diminished numbers and Trump’s increased ones, it seems fair to say that Wayne County was nearly the entire difference between defeat and victory.

So: What happened?

Was Trump’s victory a mere one-off that combined the fluky circumstances of inflation, Biden’s age, and Harris’s late entry (along with bias against her gender and race)? Or is the movement of working-class voters to the Republican column potentially more permanent? Beyond that, did the shift of Arab and Muslim voters toward Trump—or at least, away from Harris—in cities like Dearborn portend a future voting bloc in Michigan that is rising in population and power and that doesn’t feel the special historic allegiance to the Democratic Party that many minority groups have felt?

Michigan has been a bellwether state for much of its history. It backed Abraham Lincoln; it stayed with the Republicans through the nineteenth century, when the Democratic Party was a mess and rarely won; it became Democratic with FDR, then went back and forth until 1972 when it stayed Republican through Reagan and Bush Sr.; since then, it has (mostly) been part of the rising, multiethnic Democratic coalition cobbled together by Bill Clinton and Barack Obama. But now the Democrats have lost two of the last three there. And the biggest reason, certainly with respect to 2024, is a dramatic underperformance in a county where they should be building up a massive margin to cover the losses in all those rural counties. How alarmed should they be?

Even in terms of its geography, Wayne County is quirky. Due to the configuration of the Great Lakes and their connecting rivers (and to the Treaty of Ghent, which ended the War of 1812), Wayne County is both north and west of Canada. It is named after General “Mad Anthony” Wayne, who served in the Revolutionary War under General George Washington and later fought the Northwest Indian War in the Great Lakes region, which was a skirmish over what was then called the Northwest Territory and is today the states we generally think of as forming the heart of the Great Lakes region (or, if you prefer, the Big Ten Conference). Wayne was a spendthrift, drinker, womanizer, slave owner, and politician who was expelled from his (Georgia) seat in the U.S. House of Representatives for voter fraud. Nevertheless, under Washington, Wayne’s success against Indian nations—culminating in the Battle of Fallen Timbers in what is now Ohio in 1794—opened up what later became Michigan (and other lands nearby) to white settlement and statehood.

At the time, Detroit was the site of a fort held by the British, who were allies of the Indians. The entire area held about 3,000 settlers. As of 2023, Wayne County’s population is 1.75 million; that’s down from 1.82 million in 2010 and 2.67 million back in 1960. Detroit makes up about 36 percent of that. The county includes corporate headquarters of Ford Motor Co. and General Motors. While the city of Detroit may be poor, the county is more complex: Wealthy Grosse Pointe is in Wayne County (actually, there are five Grosse Pointes).

Much remains bleak on the other side of a great divide. The county’s northern border is Eight Mile Road, made famous in a 2002 Eminem film, 8 Mile, about dysfunctional family life, the street culture of the Motor City, and the world of rap and hip-hop.

In real life, “Eight Mile Road” is local shorthand code for racial animus and economic disparity between the struggling city and its more prosperous suburbs, although that vibe has lessened in recent years (the county is nearly half white and about 38 percent Black). In a wider scope, Eight Mile Road also divides less prosperous Wayne County from blue-collar Macomb County to the northeast and white-collar Oakland County to the northwest.

Harris’s problems in Wayne County begin in Dearborn, an inner-ring suburb west of Detroit that is the seventh-largest city in the state (and second-largest in the county), with almost 110,000 citizens as of 2023. Among them, 55 percent identify as having Middle Eastern or North African ancestry, the highest of any community in the United States. Their swing was foreshadowed in Michigan’s Democratic primary on February 27, when more than 100,000 voters—a quarter of them from Wayne County—cast ballots as “uncommitted.” This protest vote movement, centered in Dearborn, implied that significant numbers of voters would turn away from the Democrats if there was no change in Biden’s Gaza policy.

In 2020, Dearborn had voted for Biden over Trump by 68 percent to 29 percent. Harris made many Michigan campaign stops last fall, but she did not appear in Dearborn. Trump, sensing momentum, visited the city on November 1, telling a crowd at a restaurant called The Great Commoner of his many friends in the Lebanese community and his wide support there, despite his Muslim ban of 2017. “The Muslim population, they’re liking Trump,” Trump said. “And I’ve had a good relationship with them. This is it, this is where they are, Dearborn. We want their votes and we’re looking for their votes, and I think we’ll get their votes.”

Four days later, with Gaza policy unchanged, Dearborn voted for Trump over Harris by 42 percent to 36 percent. That swing from 2020 to 2024 of roughly 15,000 votes away from Democrats in Dearborn made up close to 20 percent of Trump’s margin of victory in the state.

Abdullah H. Hammoud, the Democratic mayor of Dearborn, said in an interview with MSNBC in the week after the election that the Harris campaign was to blame. “If you have not come to this city to speak to its families, to speak to its residents, then you will have no understanding of what actually unfolded in this last election cycle,” Hammoud told the network, citing what he called “genocide” by what he called “war criminals” from Israel. “Yes, there was a rebuke of Vice President Harris … for failing to distance herself from President Biden,” he added. The mayor said, “If you look at the predominantly Arab American precincts here in the city of Dearborn, Vice President Harris only captured anywhere between 12 percent to 18 percent of those votes. These are precincts in which President Biden captured nearly 80 percent four years ago. That should tell you how strongly people feel about the genocide unfolding right now in Gaza and the war that’s unfolding currently in Lebanon.” (Representative Rashida Tlaib, whose district includes Dearborn, and who is the only Palestinian American in Congress, declined a request for an interview.)

Had Harris visited, Hammoud said, she would have learned of memorial services in his city for relatives who died in the Middle Eastern combat, including in Lebanon. He said his followers tried to warn the Democrats for nearly a year to address Gaza. “What happened?” Hammoud asked. “They stoked hatred toward university protesters who were standing up against genocide. They wagged their finger.”

Another heavily Arab American community in Wayne County, Dearborn Heights, showed a drop in presidential votes from around 16,000 for Biden in 2020 to 9,000 for Harris in 2024. Trump won it this time with 11,000 votes. And in nearby Hamtramck, a largely Muslim community, Harris got less than half of Biden’s roughly 6,500-vote total. This after Hamtramck’s Muslim Arab mayor, Amer Ghalib, endorsed Trump. An immigrant from Yemen who is a Democrat but a social conservative who banned the flying of Pride flags in his city, Ghalib told WXYZ television in Detroit in September that he met personally with Trump, who promised to try to end the war. Further, he said the swing toward Trump among Arabs and Muslims is the beginning of a new party alliance. “There was a major disconnect between us and the Republican Party,” Ghalib said. “This has to come to an end ... there is a shifting dynamic that I am leading now, and it will have a major effect in the future.”

Not all antiwar voters in Michigan live in Dearborn or Hamtramck. Consider William Lawrence, 34, a political activist in Lansing who said he “tends to vote Democratic” but voted “uncommitted” in the Democratic primary and for Harris in the November election. “The whole party has been running away from the genocide in Gaza,” Lawrence said. “Biden and Harris ran their campaign talking about how great the economy has been, and homelessness is up 18 percent in the last year. We have camps all over Lansing.”

But will Trump change things? “People want change, and he has established himself as an avatar of change,” Lawrence said. “I don’t think he’s going to change things for the better. But struggling people will make a bet on change.”

The Wayne County drift toward Trump involved more than just the protest votes of Arabs and Muslims. Second-term U.S. Representative Shri Thanedar said his 13th Congressional District, which includes Detroit and much of Wayne County, is “one of the poorest” of the nation’s 435 districts. “People are living paycheck to paycheck,” he said. “Many of my constituents have service jobs that pay minimum wage or just slightly above minimum wage.... A disproportionate amount of young people are still getting incarcerated. We don’t have [adequate] public transportation.”

Trump, he told me, “was able to articulate some of their concerns. He more than likely will not help them and may not make their lives any better. But he surely was able to articulate some of their fears.” Of his Democratic Party, Thanedar said, “With our message, the clarity was lacking, the focus on economic, kitchen-table issues was lacking.”

Brady Baybeck, a political science professor at Wayne State University, said Republicans were better able than Democrats to frame issues around the economy. But he withheld future predictions. “It’s too early to say it’s a permanent, structural change,” he said.

More optimistic is Bernie Porn, a pollster who has worked for Democratic candidates. He said Harris lost ground here in the last two weeks before Election Day after Trump’s campaign bombarded television shows with campaign ads painting Harris in sympathy with transgender people, even those imprisoned, who would qualify for taxpayer-funded sex-change operations.

He said Harris faced an unusual confluence of circumstances involving her association with Biden, her late entry, and her race and gender. “I don’t think that Democrats are in as bad a position as they fear they are right now because they just got spanked by Donald Trump and his supporters,” Porn said. He feels race and gender played a bigger role here than many allow. “The fact that the Democratic nominee was a woman—let alone a Black woman—it would just appear that America is not quite ready yet to vote for a woman, at least not over Trump,” he said. “Black voters—especially young Black men—did not vote as much for Kamala Harris as older Black women and even older Black men.”

Porn thinks “Trump’s bluster appealed to” these voters. But he believes Michigan Democrats can grab the momentum back for the midterm elections of 2026 and the next presidential cycle in 2028. “A lot of what happened in Trump’s popularity declining in his first term is likely to happen again,” Porn said, “and that would probably bode well for the Democrats.” Porn also predicted that Trump’s desire to cut federal spending would cost him politically. “You cut two trillion dollars out of the budget and that’s some serious cuts in just about every program,” he said.

Republican pollster Steve Mitchell published a newsletter after the election that named seven groups of voters for Trump’s Michigan victory. In this order, he listed those who were young, male, Catholic, suburban, Arab American, Hispanic, and African American. He cited inflation and the economy as the major issues. “Although inflation has hurt every group, it has been especially hard on lower-income voters,” Mitchell wrote. “Because African Americans and Hispanics often fall into the lower income strata, they and younger voters (18–29) are more likely to be held hostage by inflation. Since they were so impacted by inflation, it was logical for them to vote Republican instead of Democratic.”

Every perspective differs slightly, but some overlap. One from the ground level came from Tina Nelson, an African American woman from Detroit who worked for the Democrats as a volunteer. Nelson said Harris lost because “she got thrown in” as a candidate when President Biden withdrew three months before the election. “She just didn’t get the full respect as a candidate from ground zero to build her own brand,” Nelson said. “Black folks show up when they want to, and they don’t show up when they don’t want to.” She theorized that some Black citizens voted for Trump because they knew him better from exposure on television. “Trump came from reality TV,” she said. “And what does the average, underprivileged, underserved community watch every day? Reality TV. His brand was built way before he became president. And he’s a man. And it’s a man’s world, to be honest. Unfortunate, but it is.”

Her take—at least the part about Harris’s low public profile—echoes that of Representative Debbie Dingell, who knows well Wayne County’s “Downriver” industrial suburbs, the part of the county that includes many heavy industrial factories, although not as many as there used to be. It is near Detroit’s soon-to-open Gordie Howe International Bridge to Canada and alongside the Detroit River that flows south from Lake St. Clair into Lake Erie.

As Dingell begins her sixth term in the House, her turf has shifted westward because of redistricting, and her new constituency includes Ann Arbor and the University of Michigan—but also still a slice of western Wayne County. She knows the terrain because her late husband, John Dingell, represented these Downriver communities for 59 years until she replaced him in 2015. In 2016, when she was new to the House, Debbie Dingell famously predicted that Trump could defeat Hillary Clinton in the state, though her pessimism was a minority view. As for 2024, she said, “I was not surprised that the Democrats lost Michigan,” adding, “honestly, a lot of people didn’t feel like they knew Kamala Harris.”

Dingell said she didn’t think Trump clinched Michigan until the last few weeks. But she had an inkling. “I go to [the supermarket] every week to return my bottles, and people know I’m going to be there, and they talk to me about their grocery costs,” she said. “I go to the farmers market, I go to a union hall, I meet with my veterans, I’m at events.” Dingell said she sensed “an unhappiness, an edginess to people, and they aren’t sure who really cares about them and who’s going to deliver for them.”

This would seem to echo the often-heard complaint-stereotype that the twenty-first-century Democrats are a party of highly educated “coastal elites” who care little for blue-collar people in flyover country, especially compared with Trump’s populist—some might say “demagogic”—fearmongering. If this is so, can Dingell’s side reverse the MAGA momentum? “It’s not going to come back without you putting in the work,” Dingell said. “We need to understand the message that is being sent to us. I don’t think they want to see people disagreeing and squabbling. The American people are very frustrated about a number of things and want to see things shaken up.”

One who is doing a little shaking up of his own, in a way that could portend trouble for Democrats, is Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan. After three successful four-year terms, Duggan announced that he would run for the open governor’s seat in 2026—not as a Democrat but as an independent. Democratic Governor Gretchen Whitmer is term-limited. Duggan’s gubernatorial ambitions surprised few. But his declaration of independence from the Democratic Party brought a shock. “What would happen if we … gave Michigan voters a new choice?” Duggan said in his video announcement. “I’m not running to be the Democrats’ governor or the Republicans’ governor.”

Porn, the pollster, predicted Duggan would split the Democratic vote and hand the 2026 gubernatorial election to the Republican candidate, although no top GOP candidate has yet emerged. Michigan tends to elect Democrats to the U.S. Senate, including Elissa Slotkin, who moved up last November from the House to replace fellow Democrat Debbie Stabenow, winning a very tight race. But the state tends to rotate between the parties for governor. Since 1949, Michigan has had five Democratic governors and four Republicans.

Duggan’s track record shows him capable of surprising results. He first ran for mayor in 2013 as a write-in candidate and became Detroit’s first white mayor since 1974. As the city emerged from bankruptcy, Duggan turned the streetlights back on and tore down many of the vacant homes. Crime is down, and the city population is up slightly.

“It complicates things,” Dingell said of Duggan’s candidacy.

Another possible Democratic candidate is Pete Buttigieg, the secretary of transportation under Biden. Buttigieg and his family recently moved to Traverse City, the land of Up North snowmobiles and sand dunes. The election of an openly gay governor would mark a significant pivot in Michigan’s political culture (Buttigieg has also been mentioned as a possible Senate candidate in the wake of the surprise announcement by Democratic Senator Gary Peters that he won’t seek reelection in 2026). A third top-tier contender for governor is Jocelyn Benson, the secretary of state, who announced her intention to run in late January.

As for Whitmer, informed speculation around the state (and beyond) suggests she will run for president in 2028. With the two remaining years of her second term set to overlap with the first two years of Trump’s second term in the White House, her cooperation or confrontation with the president may signal her future ambitions. Trump once referred to her as “the woman in Michigan” (colloquially this has evolved into “that woman from Michigan”). She wears the slur as a badge of honor.

She was more skeptical of her local nickname, “Big Gretch,” although it seems to resonate for a woman who sometimes wears leather clothing and projects self-confidence. Porn said Whitmer polls unusually well in both competence and likability, and that most candidates usually do well in just one. But would national Democrats be willing to nominate a female candidate for the third time in four presidential cycles?

In her autobiography, True Gretch, a short volume published last year, Whitmer wrote of being raped in college, about her divorce, and about what it was like for right-wingers to demonstrate outside her Lansing office in 2020 during the Covid lockdowns. One sign on a pickup truck said, HalfWhit Is The Reason We Need The 2nd Amendment.

And that’s not all she saw. “Swastikas,” she wrote of the scene from her window. “Confederate flags. AR-15s. And though I didn’t see this until later, one man had tied a noose around the neck of a brown-haired Barbie doll, dangling her from a pole.”

Despite its progressive lean in the last few years, the Great Lakes State still pulses with a deep undercurrent of right-wing resentment and menace among militia groups and reactionaries. For instance, last fall in Livingston County, northwest of Metro Detroit and east of the state capital city of Lansing, demonstrators with flags and swastikas protested and picketed a production of the play The Diary of Anne Frank. Two similar demonstrations took place last summer in that county. This carried echoes of the infamous rally at the state Capitol on April 15, 2020, described by Whitmer in her book, when rifle-carrying protesters milled about the building’s steps. From yet another mob, in 2023, nine plotters were convicted of or pleaded guilty to a plan to kidnap and possibly murder Whitmer in 2020.

Extremism can flourish, of course, where the economic news isn’t good and where opportunity seems scant, and that certainly has described Michigan. In his video announcing that he was bolting the Democrats, Duggan also spoke of a potential crisis acknowledged by most parties here: the declining population, relative to other states. “I believe Michigan’s biggest export is no longer our automobiles,” Duggan said. “It’s our young people. Our young people are moving out of Michigan at a rate faster today than any state in America.”

That pessimism dominated the “Growing Michigan Together” report published a year ago by a bipartisan council appointed by Whitmer. According to the report, Michigan is forty-ninth among 50 states in population growth. Other studies rank Michigan’s educational output forty-first among the states. Its median age of around 40 placed its population at twelfth-oldest in the nation in 2019. “We’re losing too many of our talented young people and failing to attract others,” the report said. “The cycle of healthy growth is broken.”

Similar mixed signals come from the heart of Detroit itself. The hopeful note is struck by the Michigan Central train station, built more than a century ago and abandoned since 1988 to be photographed as decaying “ruin porn.” Now restored to its original grandeur by Ford Motor Co., which bought it in 2018, the building reopened last year as a “destination for advancing technologies” and a tourist attraction. No trains may run through it anymore, but the rebuilding itself is a source of pride. Diana Ross, Eminem, and Jack White headlined a spectacular reopening concert that boosted the city’s national image.

But nearby, on prime riverfront real estate, there stands the Renaissance Center, built almost a half-century ago as the symbol of the city’s rebirth. Its critics see it as a white elephant, the Edsel of architecture. RenCen is struggling and soon will lose its major tenant, General Motors, which also owns the core five cylindrical towers of the seven-building complex. GM will move to a new skyscraper nearby. Although the RenCen has dominated the Motor City skyline for almost 50 years, GM may tear down two or even all five of its towers. Their circular interiors have baffled several generations of Detroiters and visitors; the shape of the place makes it difficult for abandoned office and retail space to be converted for residential use.

Below the RenCen is a 3.5-mile chain of new parks and walkways—and another crisis. A senior manager of the nonprofit Detroit Riverfront Conservancy was charged with embezzling over $40 million from his civic-minded and trusting employers. Chief financial officer William A. Smith pleaded guilty in November to one count of fraud and one count of money laundering. This is the sort of business environment found in Shri Thanedar’s district at the moment, not that he is complicit in any of it. But his turf anchors a still-significant swing state that might be near another one of its periodic tipping points on which Trump and the Republicans hope to capitalize.

When he visited the Detroit Economic Club in October, Trump both mocked and boosted the Motor City. First, he said he’d been reading for many years about Detroit’s comeback without seeing results. “It’s coming around,” he said, “and never really got there.”

Trump assured his upscale audience that Harris would make things worse. “Our whole country will end up being like Detroit if she’s your president,” Trump said. “You’re going to have a mess on your hands.” As is often the case with Trump, he promised only he could save it. “I’m telling you right now, standing here in the center of this once-great city, that by the end of my term, the entire world will be talking about the Michigan miracle and the stunning rebirth of Detroit,” Trump said.

Thanedar promised to hold Trump to those vows. “Trump talked the big talk about Detroit, and the issues, and the problems with Detroit,” Thanedar said. “I’m going to hold him accountable. How are you going to help me bring federal dollars to the district?”

It is certainly a dynamic to watch: Will Trump improve life in a swing state that swung back to him this time? Perhaps Michigan again will be a bellwether state for American politics, even if it wields less Electoral College clout than it did in the twentieth century. Back in the nineteenth century—just 17 years after Michigan joined the union—the state’s Jackson County hosted in 1854 the first mass rally of what became the Republican Party, which nominated Lincoln for president in 1860.

Times have changed in the twenty-first century, in the second reign of Trump. The Arab Muslim backlash in Wayne County against Harris over Israel’s war in Gaza shows how fresh, new political currents can quietly grow and suddenly flow like fresh water into the Great Lakes. This time, the confluence included disgruntled blue-collar union workers, inflation, and a double dose of old-fashioned racism and sexism.

As of yet, no Democratic blueprint has emerged to keep this purple state from getting redder in the future. A loss in 2028 would mean three losses out of four—and could indicate that Michigan has entered a new red phase. In other words, if Democrats can’t turn the state—and specifically Wayne County—around in the next election, they may be kissing those 15 electoral votes goodbye for a while.