The first time I taught Silvia Federici’s 1975 manifesto, “Wages Against Housework,” was during the pandemic. Federici proposes that housework—cooking and cleaning, taking care of children, spouses, the sick, and the elderly—should be compensated by the government. Most of my students, who were first-year undergraduates, Zoomed into class from their childhood bedrooms. It was a moment in the pandemic when parents of younger children were with them 24/7, and it seemed as if everyone was either sick or caring for someone who was sick. The time-consuming nature of this work, as well as its physical, emotional, and financial strains, was often in the news.

Even so, most of my students had reservations about Federici’s proposal. Housework, both when Federici wrote her manifesto and now, is mostly done by women. Wouldn’t paying for it result in women doing even more housework, and perhaps having more children than they wanted? Wouldn’t it push women out of the workplace?

Mostly, though, my students were concerned about how paying people to take care of their children and spouses would change the nature of that care: Wouldn’t it turn relationships into transactions, love into labor? How would children and spouses feel if they knew that every tender gesture or loving word was a job with a price? Perhaps, some of my students suggested, there could be a distinction: yes to wages for cooking and cleaning, no to wages for more intimate forms of care.

Federici rejects this distinction. “They say it is love. We say it is unwaged work,” her manifesto opens. “More smiles? More money.” In other words, sex with your husband is work; smiling when he walks through the door and listening to him talk about his day are work; singing your baby to sleep or cuddling with her on the sofa is work, just as much as washing her onesies or mashing up food for her to eat.

Federici was one of the founding members of the Marxist-feminist International Wages for Housework Campaign, which began in the early 1970s. Those who worked inside the home, the campaign argued, were workers exploited by capitalism. Their work is what is sometimes called reproductive labor: work that does not create products that can be bought and sold but, rather, maintains and reproduces the workers who create those products. Housework feeds the worker and makes sure he has clean clothes and a bed to rest in at night; housework likewise feeds and clothes and raises the next generation of workers. Employers profit from this labor without paying the people who do it.

The goals of the Wages for Housework campaign went far beyond giving women economic independence. By making the labor of housework visible as labor, wages would enable those who performed it to organize for better working conditions. Wages for housework was a rejection of compulsory heterosexuality: Because women would no longer be reliant on someone else’s paycheck, they would be freer to choose not to marry, to leave their husbands, or to partner with women. Those who had to work outside the home as well as within it could quit their jobs if they wanted to, since housework could become the means by which they supported themselves and their families financially. Perhaps counterintuitively, wages for housework would also enable women to refuse housework: Once housework was regarded as a job, rather than the natural activity of women, women could go on strike or choose to do some other kind of work without being seen, or seeing themselves, as aberrations or failures.

Finally, wages for housework would be a crucial tool in establishing solidarity between women, and in bringing down global capitalism. Women with jobs outside the home—especially jobs that involved care work like nursing, cleaning, or sex work—would recognize housewives as fellow workers. Husbands and wives would no longer see one another as worker and helpmeet, but as comrades who could fight together for mutual liberation.

Emily Callaci’s Wages for Housework: The Feminist Fight Against Unpaid Labor is a history of the Wages for Housework campaign and a group biography of five of its leaders: Selma James, Mariarosa Dalla Costa, Silvia Federici, Wilmette Brown, and Margaret Prescod. It is also the first history of the movement that stretches from its beginnings to the present day. All five of Callaci’s central figures are still alive, and of an age to be assembling their archives (the oldest, James, is 94). Wages for Housework draws on these archives, as well as on interviews with James, Dalla Costa, and Federici, and others who organized in the movement.

Callaci suggests that today, demanding wages for housework sounds “less strange” than it once did. Thanks to Covid and the aging populations of many countries, conversations about care work are common. (Will working-class men retrain as nurses? Is heterosexual marriage a trap for professional mothers?) Dwindling social mobility has caused many to lose faith that education and workplace productivity will lead to economic stability. “Quiet quitting” is an individual response to this loss of faith; so is self-care, when stripped of its radical origins. To revisit Wages for Housework in this moment is to encounter a collective response to many of today’s problems—albeit one that requires the complete transformation of society.

The Wages for Housework movement, as an international campaign, began in the summer of 1972, when a group of feminist activists met in Padua, Italy. There, James, Dalla Costa, and Federici, along with French feminist Brigitte Galtier, founded the International Feminist Collective. The Collective’s founding statement set out a vision of a global feminist network based on the recognition that the unwaged worker in the home is as crucial to capitalism as the worker in the factory or the office. “Class struggle and feminism for us are one and the same,” it declared.

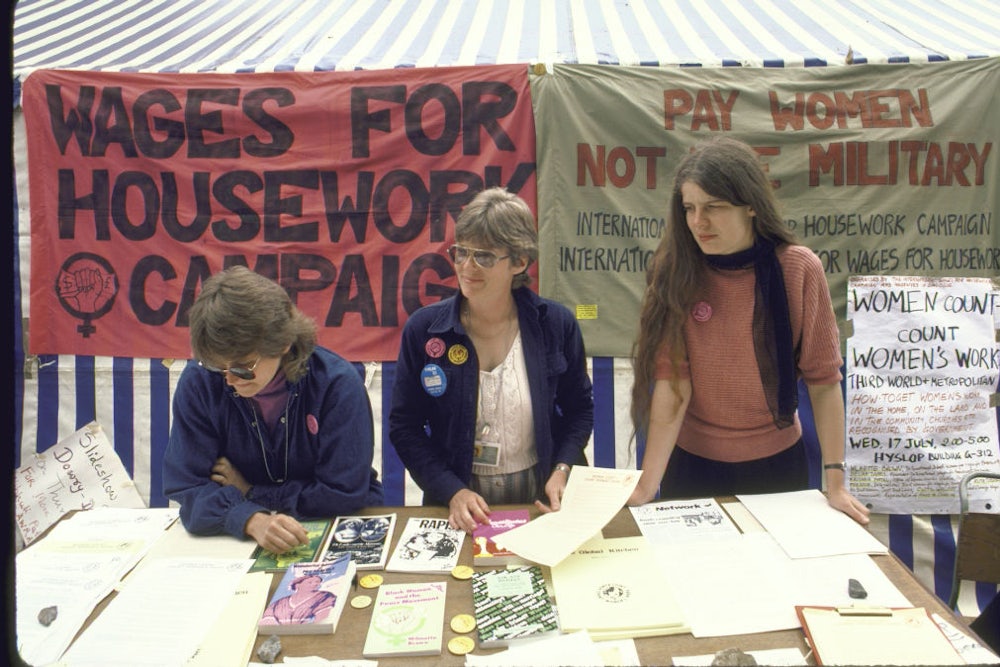

After Padua, James returned to London and set up the Power of Women Collective. Federici, an Italian graduate student in philosophy at the University of Buffalo, formed the New York Wages for Housework Committee. The Italian campaign started two years later, led by Dalla Costa, and others launched in Germany, Switzerland, and Guyana. Autonomous sister groups included Wages Due Lesbians and Black Women for Wages for Housework. In numbers, the campaign was always small—Callaci estimates its members never exceeded a few dozen. But it lobbied the United Nations and set up women’s centers in squats; it campaigned for the rights of sex workers and welfare recipients and immigrants. Wages for Housework was featured on the BBC and in the pages of Life magazine. In manifestos and at protests, on pins and pot holders, it offered an array of slogans: “Women of the world are serving notice,” “Every miscarriage is a work accident,” “No cuts, just bucks!”

Histories of the campaign tend to focus on its North American and European contexts, even as they acknowledge that the movement always had a global and anti-imperialist component. Callaci, who is a historian of modern Africa, illuminates the time her subjects spent in Africa and the Caribbean, and its influence on their politics. James, born into a radical working-class Jewish family in Brooklyn, married the Trinidadian Marxist historian and activist C.L.R. James and lived with him in Trinidad before settling in London. Teaching in Zambia, Wilmette Brown was disturbed to find that the World Bank made aid conditional on population-control measures, and equally disturbed by the social pressure that resulted in women having more children than they wanted. Margaret Prescod grew up in Barbados in the final years of British colonial rule. Her ancestors’ unpaid labor had enriched the United Kingdom and the United States; now, their descendants moved to those countries and worked long hours for low pay—often while their children remained in Barbados, cared for by grandmothers and aunts.

Callaci’s initial interest in Wages for Housework, however, was personal rather than academic. As a teenager in the 1990s, she absorbed the idea that “my liberation would come through education, creative expression, and professional success”—in other words, through escaping housework, not identifying with it. But when Callaci had her first child, she realized escape was impossible. Wages for Housework gave her a language to understand her new circumstances, yet she retained some ambivalence about whether she did, actually, want what the campaign demanded. Did she want to think of herself as raising future workers, whose labors would support capitalism? Like my students, she worried about imagining the time she spent with her children as a job, and the expression of her love for them as something that had financial value. (Wages for Housework campaigners would counter that Callaci’s, and my students’, discomfort was discomfort with the workings of capitalism; wages for housework merely makes those workings visible.)

Callaci was not the wife of a factory worker imagined in some Wages for Housework material, or the single, Black, or immigrant mother imagined in others. She had a full-time job as a history professor and a male partner with whom she split the housework. Even so, counting the second shift, she was working 18-hour days. Furthermore, she was only able to keep her paid employment through outsourcing childcare—and then only because the women who cared for her children were paid less for their work than she was for hers. This too was part of the Wages for Housework campaign: drawing attention to the fact that the success of some women in the workplace, often touted as a measure of equality, was made possible only through the undervaluing of other women’s work at home and abroad.

Each of the five women at the center of Callaci’s book came to the movement from experience of, and often frustration with, organizing in other leftist and feminist circles. James, an anti-racist activist who had worked in a factory in Los Angeles, bridled at the middle-class preoccupations of the mostly white English Women’s Liberation movement. Dalla Costa, a political scientist and labor organizer, was sick of organizing with male Italian Marxists who treated women merely as typists and girlfriends. Wilmette Brown joined the Black Panthers while a student at Berkeley but struggled with the group’s emphasis on masculinity and heterosexuality, which required her to conceal that she had a life outside the Panthers as an out lesbian. She joined a Black women’s consciousness-raising group but found it too passive: “I was fed up with consciousness-raising. I already felt pretty conscious.” When she read Dalla Costa and James’s essay The Power of Women and the Subversion of the Community, she found her cause: “I knew that my fight as a lesbian was a fight against doing the work that women were supposed to do.” She and Prescod, both in New York, established Black Women for Wages for Housework.

Many of the campaign’s auxiliary demands are still made in some form today—free state-provided childcare, a 20-hour workweek, the decriminalization of sex work—but Wages for Housework shows how the movement developed in response to the specific political and economic climate of the 1970s and 1980s. Wages for Housework pointed out that the austerity of the period was only possible because governments know that, when social services are cut, women take on more unpaid work to fill the gaps. While many feminist campaigners were focused on securing the Equal Rights Amendment that would outlaw sex discrimination, Prescod and Brown fought to protect welfare payments for women, which were under threat—and for those payments to be understood as wages rather than charity.

The gas disaster at Bhopal in 1984 and the nuclear explosion at Chernobyl two years later, as well as Brown’s cancer diagnosis, prompted Brown to understand housework as labor that not only sustains capitalism but also repairs its harms. As Callaci writes, Brown in particular pushed the Wages for Housework campaign to look far beyond the nuclear family, into “cancer wards and urban ghettos with toxic soils and scenes of police violence … into the war zones in the aftermath of American imperialism where poor women cared for ravaged bodies and lands.” In Vietnam, housework includes caring for those with cancer or birth defects caused by the toxic defoliant that the U.S. sprayed on the country during the Vietnam War. In the U.S. and around the world, it includes looking after children with asthma caused by inner-city pollution, or with lead poisoning caused by unsafe water or soil.

Callaci acknowledges that the Wages for Housework campaign could be off-putting to those outside the movement: its members too dogmatic, its ideas too opaque or abstract. She also admits to feeling frustrated by the movement’s lack of a clear “instruction manual toward liberation” or even an agreement on how the desired wages should be calculated. Perhaps because of this frustration, Wages for Housework focuses more on the campaign’s larger ideas and actions than its day-to-day decision-making and internal debates. Yet Callaci’s brief descriptions of these debates are some of the book’s most interesting moments. Did the campaign really want to get money into the hands of women doing housework (often Brown and Prescod’s focus), or was it more interested in enabling women to refuse housework (Federici and Dalla Costa)? In 2022, James told Callaci, “To be a member of our movement, there is only one requirement: you have to want Wages for Housework for yourself.” But when Callaci asked Dalla Costa, a professor of political science, what the campaign had meant to her, her answer was directly at odds with James’s view: “It wasn’t personal,” she said. She had simply believed that the campaign offered the correct analysis of capitalism.

By the end of the 1970s, the Italian Wages for Housework campaign and the New York Committee had disbanded. Dalla Costa and James, longtime collaborators, fell out for reasons both personal and political. Brown left the campaign in 1995. At the beginning of the pandemic, James and others renamed the Wages for Housework movement “Care Income Now”; it now exists under the banner of the Global Women’s Strike.

“We were worn out,” Dalla Costa has said, recalling the end of the Italian campaign. “After so many struggles and so much time spent organizing, we couldn’t detect even the outline of a transformation of our society.” In 2022, the value of unpaid domestic and care work across the world, almost three-quarters of it done by women, was estimated at $11 trillion. But that this figure exists at all suggests some kind of transformation: The role of unpaid labor to the global economy is no longer as invisible as it once was. (In 1985, members of the Wages for Housework campaign, led by Prescod, pushed the U.N. to call on governments to quantify the value of women’s work.) On the other hand, simply recognizing the existence of unpaid work is of very limited help to many of those who do it.

In her book’s epilogue, Callaci points to the 2021 expanded Child Tax Credit as a recent example of the United States giving money to people caring for children. The program, which dramatically reduced poverty levels across the country, was killed by Democratic Senator Joe Manchin’s opposition. Publicly, Manchin said that extending the expanded CTC would discourage women from seeking paid work, as if such work were inherently superior to caring for children. He also reportedly feared that parents would spend the CTC money on drugs—ignoring the fact that people who work outside the home are perfectly able to use their paycheck to buy drugs. Framing the CTC payments as exceptional benefits for children—not as wages for care work—made them all too easy to cancel.

There is much about the Wages for Housework campaign, with its squats, slogans, and manifestos, that feels firmly of the twentieth century. Yet its flinty analysis of the political economy of the family offers a valuable alternative to the reformed “care economy” agenda that seems to have died with Kamala Harris’s campaign. When the bodily autonomy of women and trans people is denied, when women without biological children are mocked, a framework that starts with gender and can extend to foreign aid, environmental damage, and welfare cuts is compelling. Beyond that framework, Wages for Housework offers something more powerful still: a vision of a world in which the hard, loving work of reproduction and repair is at once valued and optional.