In “The Many Faces of R. Crumb,” a comic from 1972, the eponymous underground cartoonist offers readers a crash course in his various personae. There’s Crumb the “long-suffering” artist, bearing the scars of stigmata as he hunches over his drawing table. There’s Crumb the “sentimental slob,” weeping into his booze while treacly music plays, and Crumb the “free spirit,” wandering down the highway with a suitcase and a bindle. There’s Crumb the businessman, the misanthropic crank, and the “monumental egoist.” But the version of Crumb entrenched in popular culture is Crumb the “sex-crazed fiend and pervert.” For more than a half-century, he has been a carnival barker of the straight male libido, hyping its excesses and directing our gaze to its more outré sideshows. His comics almost hyperventilate with perversion: incest, scatology, necrophilia, and fetishes. He has a weakness for legs and asses, which he renders as meaty trunks. He favors women who look “like they grew up on a farm digging irrigation trenches,” he once told an interviewer.

Peculiarity seems to have run in Crumb’s family. His mother was a depressed amphetamine popper, and his father a terminally disgruntled Marine. Crumb’s older brother—a comics prodigy himself—ended up alternately institutionalized or housebound, in a soft fog of tranquilizers and stifled homosexuality; he committed suicide at 49. As an adult, his younger brother—also an artist—roomed in a grubby residential hotel and swallowed cotton to purify himself.

The family’s dysfunction was captured on film in the 1994 documentary Crumb, presented, fittingly, under the imprimatur of David Lynch. Scene after scene is punctuated by Crumb’s jittery pneumatic laughter. His brother’s pharmaceutical wilt, his mother’s spongy babble, an ex-paramour’s wounded reminiscences, the old homestead dank with cat piss—all of it is fodder for Crumb’s bemusement. You get the sense he relishes all of this abjection being witnessed and recorded, as if to say: My cartoons don’t seem so fucked up now, do they? Merciless and ironic, Crumb stews in his own acids and sees everything—the whole modern world—as one debased punch line. If he weren’t funny, he’d be intolerable.

Crumb: A Cartoonist’s Life, a new biography by the curator and critic Dan Nadel, wades into Crumb’s psyche. Whereas Crumb the documentary plays out like a grimy picaresque, Crumb the book is orderly and analytical, as much a history of underground comics as a pathology of Crumb. Nadel argues that Crumb is one of the “most profound and influential artists of the twentieth century,” a claim that would have been unthinkable in the 1960s. His profundity is partly a function of ruthless introspection; the same impulse that drives Crumb to admit his sexual compulsions also spurs him to unleash his scabrous vision of society, along with gentler family portraits and slice-of-life vignettes. His technical virtuosity and imaginative range transcend the ephemerality of single-gag comics. Crumb’s work chronicles the pressures of modern life on the groin and nervous system of one highly vibratory man.

Nadel distills Crumb’s obsessions as “Mommy; powerful women; acceptance; revenge.” Of this quartet, revenge may be the purring motor of Crumb’s universe. In a screed titled “The Litany of Hate,” included in the compilation The R. Crumb Handbook, from 2005, he pinpoints his antagonists: mass media, contemporary pop music, architecture post-1955, organized religion, government, nature, and humanity itself. Even his Dust Bowl wardrobe—tweed jacket, cuffed trousers, fedora—personifies his style of vindictive nostalgia. Crumb feels like a man out of sync, dislocated, and yet perfectly calibrated to channel modern America’s psychoses.

Nonetheless, Robert Crumb was born at a fortuitous moment: specifically, Philadelphia, 1943. As Nadel notes, the late 1940s and early ’50s were the comedown of a long comics heyday that included Little Lulu, Pogo, Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories, Dick Tracy, and DC Comics superheroes. Horror comics—The Vault of Horror and Tales From the Crypt, among others—were just rolling off the presses, along with the debut of Mad magazine with its subversive spoofs. Following the atrocities of World War II, Nadel suggests that comics “became a place to cram all the PTSD, atomic anxiety, and existential fear that could fit between two covers.” This work so scandalized the nation’s taxpayers that Congress convened hearings on the dangers of comics in 1954. As a result, the industry adopted a code of ethics that Crumb and others would giddily dismantle in the coming years, including the injunction to nix all scenes of “depravity, lust, sadism, masochism.”

Directed by the unhinged eldest brother, Charles, the five Crumb siblings cranked out their own comics each month in a kind of Disney knockoff sweatshop. “He’d constantly ask if I had the latest issue done, and remind me of the spin-off bimonthly or the upcoming Christmas annual,” Crumb later said of Charles. “I would often work fast just to fill the pages.” Crumb hawked his comics by mail or occasionally peddled them door-to-door.

In 1962, Crumb moved to Cleveland to work for American Greetings. Although he described himself as just one of the “laboring ants”—an underling among 600 such employees—he was rapidly promoted to the “upper echelons of the company’s staff artists.” Two years later, he met an 18-year-old college freshman named Dana Morgan. “I was very attracted to her physically. Big, robust creature … big legs,” Crumb recalled. The two lost their virginity to each other and got married barely five months later. They decamped to Europe for a honeymoon that turned into an eight-month sojourn, a trial run for Crumb’s permanent exile almost 30 years later. When they returned stateside in 1965, Crumb and Dana took their first hit of LSD together. “For Robert, there is life before LSD and life after,” Nadel writes.

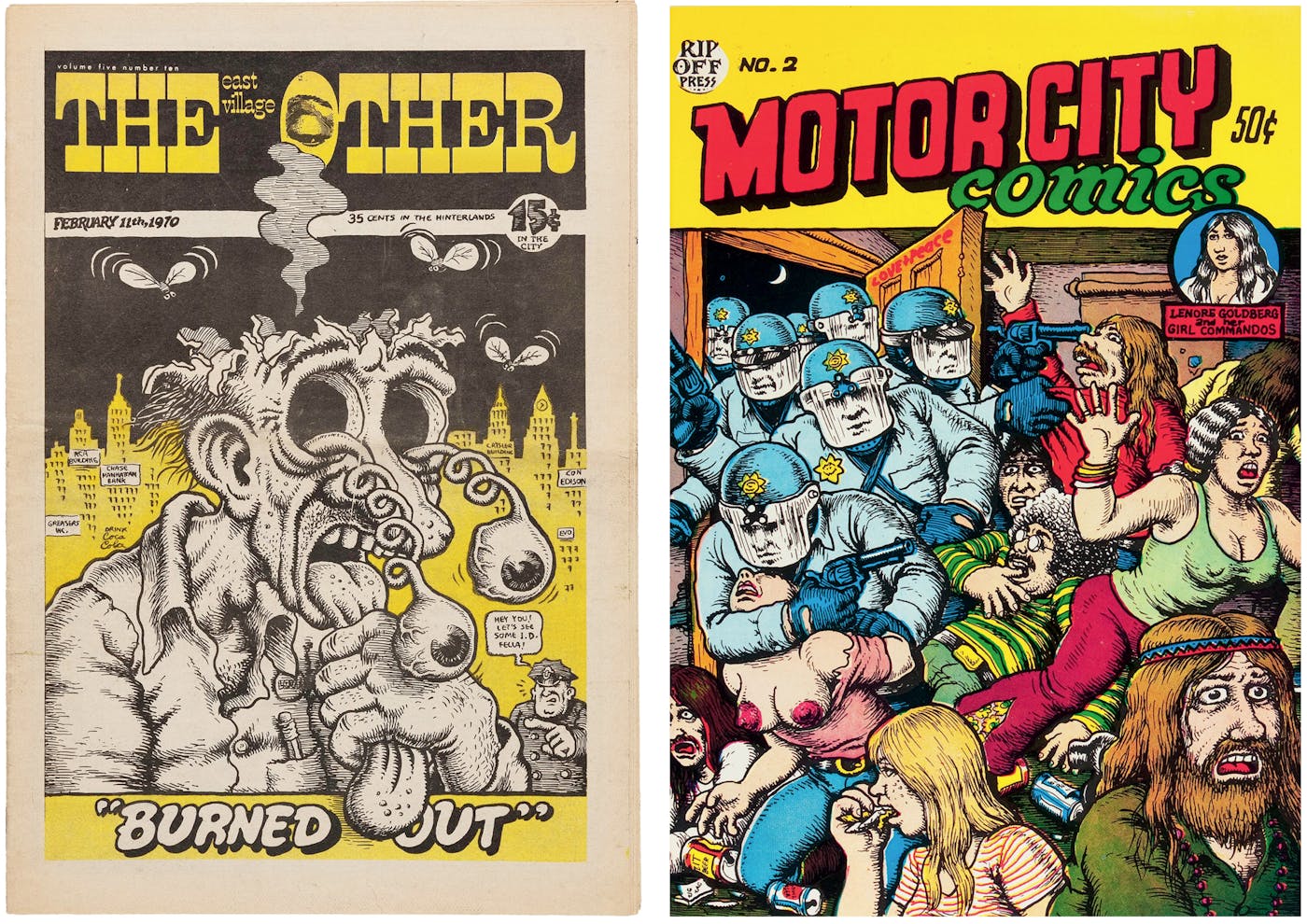

If acid expanded Crumb’s consciousness, his discovery of underground comics in late 1965 was the real epiphany. Underground newspapers—The East Village Other, the Los Angeles Free Press, the Berkeley Barb—introduced him to a new breed of cartoons. “All of these strips used the panel-to-panel form of comics to hold drawings,” Nadel writes, but they forwent “the telltale big feet, joke setups, and musical rhythms” of traditional comics. Inspired by these debauched comedies, Crumb revamped his own storytelling. In 1966, his “Har Har Page,” a 24-panel strip later included in Zap Comix, set what Nadel calls “the inadvertent prototype for everything that came after.” Proceeding with the rubberiness of a wino’s monologue, “Har Har Page” is a simple cat-and-mouse story, only here the prey is a woman victimized by a nose-picking ogre. He wipes snot on her back and menaces her with a fleet of buses. She throws a toilet at him; he eats her foot. In the final panel, he invites her to come with him and think about fried chicken. “It is misogynist, profane, surreal, and in bad taste,” Nadel writes. In other words, pure R. Crumb.

In 1967, Crumb relocated to San Francisco on a whim, where he found his comics in demand at underground newspapers and at men’s magazines such as Cavalier. In short order, he consolidated his cast of characters, a lowlife and oversexed lot whom he describes as “psychotic manifestations of some grimy part of America’s collective unconscious.” Mr. Natural, the little bald guru with the Old Testament beard, spouts mystic aphorisms but is really a cynical horndog. Fritz the Cat, one of Crumb’s earliest creations, is a suave hedonist whose sexual escapades read like hetero male wish fulfillments. (In 1972, Fritz starred in Ralph Bakshi’s X-rated animated film, which has grossed over $100 million to date. Crumb denounced the movie and published a comic in which Fritz’s ex-lover murders him with an ice pick.) Snoid is a diminutive sex fiend-cum-misanthrope. And most vexing is Angelfood McSpade, a character congealed with every racist female stereotype imaginable. She’s a nymphomaniac from “darkest Africa,” depicted in tribal garb and with features that mimic blackface minstrels or nineteenth-century Sambo art.

Crumb’s treatment of race, like his treatment of gender, is one of the more alienating features of his work. You either take his word that it’s all satirical, or you limp away insulted. To his credit, Nadel doesn’t moralize or scold. Crumb insists that his Black characters are “the embodiment of white people’s stereotypes of blacks, what they hate and fear, as well as envy, about what they think black people are.” In his 1968 comic “Whiteman,” an everyman in a rumpled suit is “on the verge of a nervous breakdown” as he lurches through a nondescript city. Suddenly, he’s accosted by a “parade” of Black marauders who pull down his pants in a humiliating reversal of the supposed social order. “You jis’ a n----- like evva body else,” one of the hooligans shouts. The white male’s deepest fear—emasculation—is here played for laughs. “Whiteman” also exemplifies the artist’s technique: Crumb exaggerates his personal anxieties past the point of ridiculousness, so that what begins as typical homespun bigotry morphs into a burlesque of cultural or historical maladies.

This method wasn’t well-received by feminists, who rebuked Crumb’s portrayals of rape and torture. “I was a ‘male chauvinist’ asshole,” Crumb later conceded, although he also maintains his right to dredge the dark sewers of his imagination. In “Joe Blow,” a comic from 1969, he lampoons family values and the sanctity of childhood in a story of amiable suburban incest; it’s like a 1950s sitcom stripped to its corrosive id. In “On the Bum Again” (1970), Mr. Natural becomes the caretaker of a fellow train passenger’s abandoned baby (or perhaps an adult disguised as such), whom he mollifies by feeding semen straight from the tap. Mr. Natural believes he’s doing the right thing, but the disjunction between his good intentions and what’s socially reprehensible accounts for the comic’s vulgar brio.

While Crumb had a devoted following in the underground press, buoyed by his 1968 album art for Cheap Thrills by Janis Joplin and Big Brother and the Holding Company, mainstream publishers were wary of his raunchier material. In comic-book series such as Snatch and Zap, both of which debuted in the ’60s, Crumb unleashed his most extreme, taboo concoctions. He takes the “idiom of pornography—a bastion of fantasy for freaks and squares alike—and” turns “even that inside out,” Nadel writes. In the late 1960s, when he was putting together the pointedly titled Head Comix, an anthology for the respectable Viking Press, he received a memo from his editor admonishing him: “no cunt lapping, cock sucking, ass licking, or shit-eating, please. Now is that too much to ask?” Crumb, like most of his peers in the world of underground comics, wasn’t inclined to censor himself.

In 1968, he unleashed his most famous image—his Mona Lisa. Its slouchy insouciance resonated across classes and generations. In the cartoon, titled “Keep on Truckin’,” various men promenade, canted far back, legs thrust out in an affront to both anatomy and worldly concerns. Nadel notes that “truckin’” was “slang for ‘doing all right,’” as well as a dance from the 1930s. The text in Crumb’s strip was adapted from a 1936 song by the blues guitarist Blind Boy Fuller. Bucking copyright laws, the image appeared everywhere almost overnight, a bootlegged koan on coffee mugs, T-shirts, bumper stickers, and posters. It was an antidote to that year’s assassinations and overseas slaughter, a self-affirmative mantra that tapped into the counterculture’s “go with the flow” ethos. For Crumb, it was a lark. A hassle. A hit of fame.

By the early 1970s, Crumb was living on a communal farm in Northern California with Dana and their young son, Jesse, born in 1968. It wasn’t idyllic out in the boondocks. “Dana was beset by migraines and was deep into Percocet, sometimes locking herself in her bedroom ... for two to three days at a time,” Nadel writes. The couple had an open marriage, which occasionally spiraled into melodramatic dustups. One of Crumb’s aggrieved mistresses threatened to drown herself in a shallow river.

Into this mix sidled 24-year-old cartoonist Aline Kominsky. On their first meeting at a friend’s apartment, Crumb complimented her “cute knees” and then whisked her upstairs where he began to “grope” and “play with” her face. The pair soon became a couple, romantically and creatively, and lived on the same compound with Dana and Jesse. Aline’s work, like Crumb’s, is unflinching. The cover of Twisted Sisters, a comic from 1976, shows her heaped on the toilet, panties around her ankles, legs stubbled. “I look like a 50 yr. old businessman!” blares a thought bubble. Dirty Laundry, the first comic they collaborated on, introduced a “comedic duo, like George Burns and Gracie Allen.” They went on to publish more than 300 pages of joint work over the years. “Together they made stories out of their own hang-ups, pushed the medium, and offered a new, cringe twist on their comics,” Nadel writes. Crumb divorced Dana in 1977 and married Aline the following year.

As Crumb’s homelife settled somewhat, the comics industry imploded. Nadel’s book doubles as an incisive history of the business of underground comics—a phenomenon enabled by the proliferation of alt-weeklies, print syndication, and the distribution network of head shops. Artists such as S. Clay Wilson, Gilbert Shelton, Spain Rodriguez, and Kim Deitch boasted cult followings, and long-running comic-book series (including Crumb’s own Zap and Weirdo) sold well enough. The Bay Area and a few Midwestern outposts were hubs of comics publishing. By the late ’70s, though, the market was overheated, and reams of trash overtook the good stuff. According to Nadel, more than a thousand titles were cranked out between 1970 and 1972 alone—“a lot of it barely readable.” Worse, in 1973, the Supreme Court established a legal definition of obscenity that put underground comics in jeopardy. Publishers and retailers grew skittish. Sales tanked.

Crumb endured his own setbacks in those years: a ballooning IRS debt and a feeling of stagnation. He was only in his thirties but felt like a dinosaur act. Still, he also logged some triumphs: the birth of his daughter, Sophie, in 1981, a series of meticulous portraits of blues and jazz musicians that attest to his craftsmanship, and a milder, even quotidian, tone to his work. His “legacy began to shift from door-busting visionary to contemplative chronicler of the everyday,” Nadel writes.

Underlying this shift was an incongruous streak of sentimentality, which itself was linked to Crumb’s reverence for the past—evident in his massive collection of 78 rpm records. These crackly shellac recordings of hillbilly songs, blues ditties, and dance orchestras evoked “the good-time social music of a vanished urban civilization, a lost world of smokestack factories [and] clanging trolley cars,” Crumb wrote. He idealizes this sepia-toned moment of prelapsarian Americana—recent enough to accommodate automobiles and pollution, but distant enough to conjure a fantasy of simple living. You suspect that part of what he pines for is the visual harmony of a land unencumbered by capitalist eyesores: billboards, franchises, prefab buildings that elicit a nauseated déjà vu.

In the 1979 comic “A Short History of America,” Crumb depicts the successive commercialization of a once-bucolic patch of wilderness. What begins as empty woodland in the first frame gradually incorporates train tracks, a road, and a wood-frame house. By the ninth frame, all of the trees have been axed, the road is paved and crosscut with telephone lines and traffic lights, and the house is painted (defaced) with a Coca-Cola ad. The final frame is cluttered with traffic and a row of synonymous apartment buildings. The former house is now a Stop ’n’ Shop with a parking lot. It’s an acerbic vision, but also nostalgic and old-fashioned, of a piece with Crumb’s fedoras.

In 1991, weary of U.S. conservatism, the Crumbs decamped to a medieval village in southern France. (Crumb sold six sketchbooks for about $100,000 to pay for the house.) It was an ancient place that abetted his more woo-woo impulses—astral projection, for example, which Crumb claims to have achieved.

With the release of Crumb the film in 1994, made over several years by his friend the director Terry Zwigoff, Crumb achieved a new level of commercial and cultural currency. The film won critical plaudits and took the documentary prize at Sundance. It also spawned a round of projects that culminated in Crumb’s surprisingly faithful adaptation of the Book of Genesis in 2009, which Nadel dubs a “two-hundred-page masterpiece.” The years since have been more fraught, marked by bereavements and the rude bushwhacks of aging bodies. Aline died of cancer in 2022. The couple’s final collaboration was “Crumb Family Covid Exposé,” in which Crumb dramatized his anti-vax paranoia—a lingering distrust of establishments, scientific and otherwise.

Yet, Crumb, now 81, is something of an establishment figure himself. He has lived long enough for his work to be fêted as fine art. He is mentioned or exhibited alongside Philip Guston, Peter Saul, H.C. Westermann, Jim Nutt, and other once insurgent image makers who push the boundaries of what is acceptable, what is serious. His fingerprints are all over Ren & Stimpy, The Simpsons, Family Guy, and other animated series, as well as a subsequent generation of audacious, formally ambitious graphic novelists such as Art Spiegelman and Daniel Clowes. His characters have infiltrated pop culture to become, themselves, figments of the “collective unconscious” they were intended to satirize. At its best, Crumb’s version of the twentieth century feels as timeless and earthy as Brueghel, an artist to whom he’s been compared. Crumb’s comics offer a similar sense of fleshy commotion, a panorama of human vice and folly presented without apology and with a caustic moral: Men are doomed; life is punishing; feast your eyes.