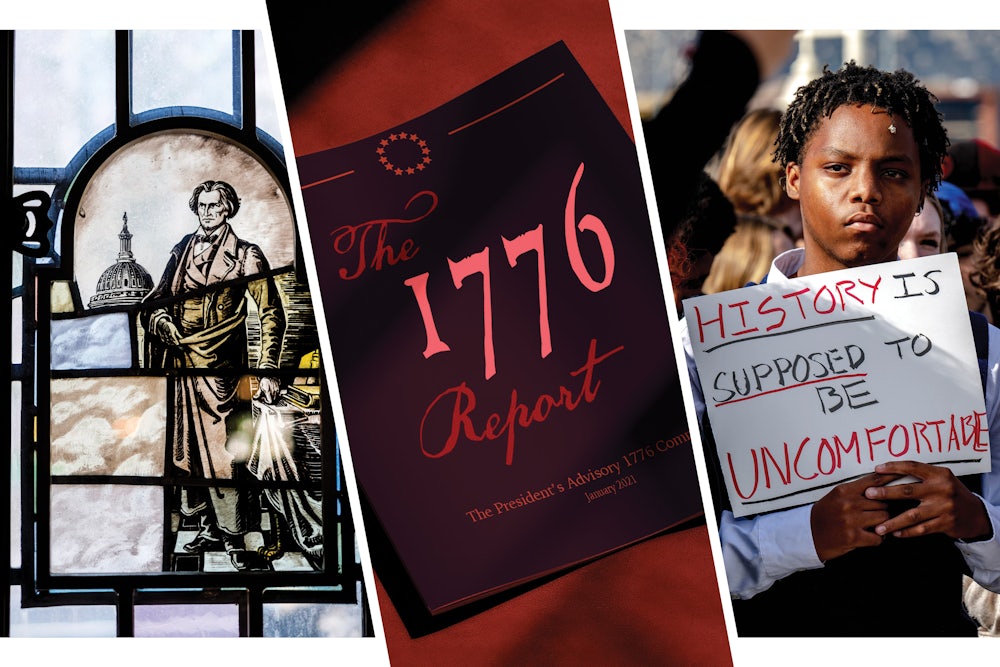

It is not unusual for American presidents to have an interest in history. In some cases, such as Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, and John F. Kennedy, they even published works of history (for Kennedy, it was probably more “published” than “authored”). Presidents Barack Obama and Joe Biden even invited distinguished historians to the White House for conversation. In nearly all cases, the records of the executive office indicate an ongoing concern for their legacy. Until the current resident of the White House, however, no president has tried to directly intervene in what Americans learn about history.

Although he shows little indication of reading history or knowing much beyond generalities about a handful of presidents he admires, Donald Trump claims to know what Americans are learning in classrooms, historic sites, and national museums. Soon after assuming office, he issued executive orders that accuse history teachers and public historians of polluting the minds of students and visitors to museums and national parks with histories driven by a “corrosive ideology” that generates “divisive narratives that distort our shared history.” The White House has stated the proposition clearly:

Over the past decade, Americans have witnessed a concerted and widespread effort to rewrite our Nation’s history, replacing objective facts with a distorted narrative driven by ideology rather than truth. This revisionist movement seeks to undermine the remarkable achievements of the United States by casting its founding principles and historical milestones in a negative light…. [O]ur Nation’s unparalleled legacy of advancing liberty, individual rights, and human happiness is reconstructed as inherently racist, sexist, oppressive, or otherwise irredeemably flawed. Rather than fostering unity … the widespread effort to rewrite history deepens societal divides and fosters a sense of national shame, disregarding the progress America has made and the ideals that continue to inspire millions around the globe.

These accusations are neither new nor original in how they are worded. They closely resemble legislation that has been passed in approximately 20 state legislatures over the past five years, describing a similar scenario in each state’s history classrooms and delineating a long list of prohibitions, with particular buzzwords such as “critical race theory,” “gender ideology,” and other “divisive concepts” that proponents consider insufficiently patriotic. Without any evidence, advocates of this legislation, like the president, claim that current trends in history education make certain students feel guilty or ashamed of their nation, their heritage, and their ancestors.

These “divisive concepts” laws are generally worded to resemble a push poll: Something must be prohibited because presumably it is happening. Idaho, for example, specifies “divisive concepts” that “exacerbate and inflame divisions on the basis of sex, race, ethnicity, religion, color, national origin, or other criteria in ways contrary to the unity of the nation and the well-being of the state of Idaho and its citizens.”

The irony here is that history teachers, rather than inflaming divisions, are actually helping students understand divisions that undeniably exist. They are teaching histories that will help students participate in a civic life that might address these divisions. Leaving the next generation ignorant of this historical knowledge, of the institutions, cultural practices, and processes that have either created or nourished division, will only perpetuate and deepen division.

Moreover, a nation that doesn’t understand those aspects of its past that render different groups likely to see past and present so divergently can never heal its wounds—the deep divisions that undeniably exist in our nation—without understanding their origins, evolution, and continuing impact on the body politic. Legislation designed to create unity by erasing actual (and easily documented) historical divisions will instead be the engine of new conflicts, new impediments to national unity.

The justification and logic of the legislation and the executive orders rest on an inaccurate depiction of the landscape of history education. Rather than describe actual classroom conditions, these radical ideologues craft portrayals designed to arouse anger and fear. The original authors of this language—generally conservative activists residing mostly in East Coast think tanks (yes, imagine Iowans realizing that their legislators have approved language written literally on Madison Avenue in New York, by a group called Civics Alliance)—have no idea as to the actual patterns of history education across the nation, or the culture of social studies teachers. They have cherry-picked from easily and widely publicized outrages, familiar and believable to anyone within the echo chambers of social media and conservative news outlets.

The March 27 executive order titled “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History,” for example, claims that historians and teachers have reconstructed American history “as inherently racist, sexist, oppressive, or otherwise irredeemably flawed.” Other than scattered, glaring anecdotes from a few of the hundreds of thousands of high school social studies classes in the United States, there is no evidence of such a trend. Indeed, just the opposite: The American Historical Association’s recent massive study, American Lesson Plan—a thorough examination of state standards, district-level social studies mandates and guidelines, and surveys conducted by the National Opinion Research Center, or NORC, at the University of Chicago—found that official curriculum and classroom practices generally eschew extremes of the left and right. Thomas Jefferson gets his due; Robert E. Lee gets what he deserves.

Specific aspects of the AHA’s research belie both Trump’s accusations and the claims of “divisive concepts” rhetoric decrying an alleged epidemic of radical anti-Americanism in classrooms. Trump’s announcement of his 1776 Commission and other messaging from the White House and the secretary of education, for example, repeatedly cite The New York Times’ 1619 Project as one of the “corrosive” influences on American classrooms. These materials, however, clearly stand outside the mainstream of social studies pedagogy—as do the outdated interpretations of slavery and Reconstruction that the 1619 Project claims are still infecting young minds. When looking for materials to enhance their knowledge of particular topics, or to share with students, public school teachers, according to AHA and NORC survey data, look initially to the websites of the Library of Congress, National Archives and Records Administration, the Smithsonian, and even their local libraries.

The legislation and executive orders leave history teachers in a difficult and vulnerable position. The president says they are teaching “hateful lies about this country.” Parents read in the media and hear from conservative activists that our public schools are “teaching students to hate America.” Tenure protections for secondary school teachers in most cases are considerably weaker than in higher education. So, best be careful.

Consider, for example, that in many states that have passed “divisive concepts” legislation, it is illegal to introduce into the classroom claims that “one race or sex is inherently superior to another” (also mentioned in an executive order). Where does that leave an American history teacher who should explain to students the very straightforward fact that, for more than a century, various state laws rested on that very assumption: One race is superior to another. Yes, if one reads carefully, of course a teacher can include this in the curriculum. But that doesn’t necessarily track onto what students might relate to their parents after an hour in class where they were paying slight attention. Or a parent misunderstanding what their child relates. Or the slippage from class lesson to student to parent to school board member. For a teacher, the chilling effect is substantial.

From the White House to state legislatures, the history these politicians and activists are protecting is straightforward: We’ve built a great country, with some bumps along the way. Those bumps were exceptions to the overall structural and cultural trends. Texas, like many other states, prohibits teaching that “with respect to their relationship to American values, slavery and racism are anything other than deviations from, betrayals of, or failures to live up to, the authentic founding principles of the United States …”

No. Slavery and racism were much more than mere “deviations.” Most of the Founders owned enslaved people. Many white Americans, including the president, think we should restore memorials to men who committed treason during the Civil War on behalf of the supposed right of some humans to own, buy, and sell humans. Hardly evidence of a mere “deviation.”

Moreover, few professional historians would deny that racism has been a central aspect of American institutional and cultural development. We can argue over “a” or “the.” Better yet, let the students debate it in their history classes. Advocates of a “patriotic education” that is largely a celebration of “American exceptionalism” (note: All nations are exceptional in their own way) consider this encouragement to students to wrestle with difficult questions a form of “indoctrination.” We call it “education.”