Calla Hayes, the executive director of A Preferred Women’s Health Center in Charlotte, North Carolina, is used to protesters. The clinic sees thousands of anti-abortion demonstrators outside of its doors each year; the same group of faces greets her each day.

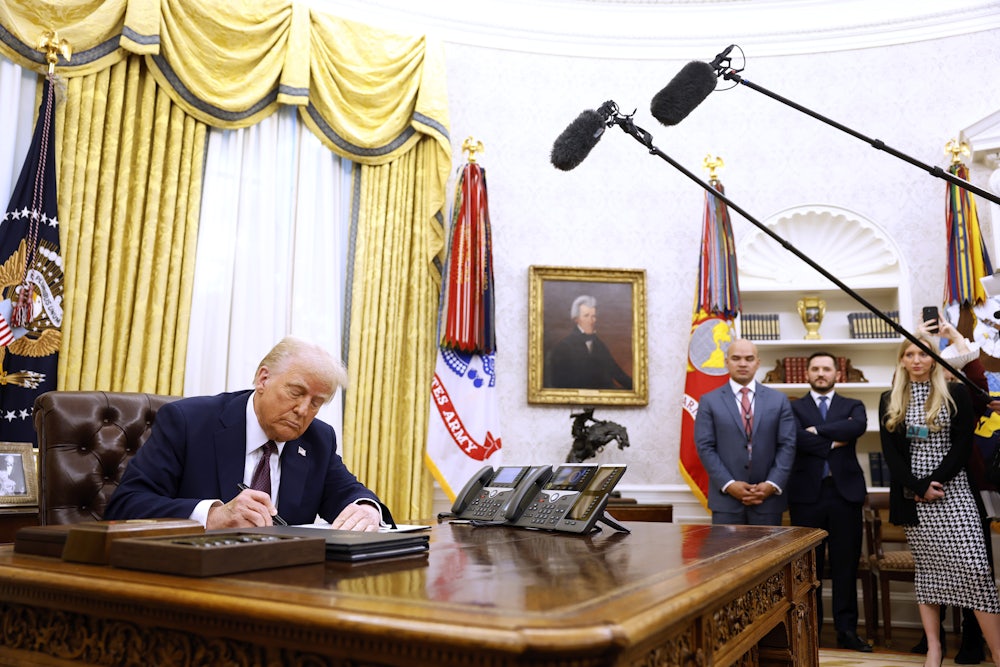

But in the months since President Donald Trump returned to the White House, she’s seen a change in their behavior. Hayes believes that turnover in the White House, along with the Supreme Court decision nullifying Roe v. Wade in 2022, has emboldened the activists outside her clinic’s doors to start “pushing boundaries.”

“They’re just, like, giggling with glee, because they’re getting to push and see how far they can go,” said Hayes about the newly empowered anti-abortion protesters.

The shift in atmosphere came as the Trump administration scaled back enforcement of the Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances, or FACE, Act, which was approved on a bipartisan basis in 1994. That measure outlawed obstruction and property damage intended to hamper a clinic’s ability to conduct reproductive health services, including abortion. But with the Trump administration’s order on the FACE Act, a bomb threat like the one Hayes’s clinic received in the summer of 2024 is no longer considered to be a threat worth reviewing by the federal government; indeed, the FBI has communicated to Hayes that it has dropped its investigation of the incident.

In a memo announcing its change in policy, the Department of Justice argued that the FACE Act was a “prototypical example” of weaponizing the legal system against conservatives. The agency will now only enforce the law under “extraordinary circumstances,” such as cases involving “death, serious bodily harm, or serious property damage.” Shortly after taking office, Trump also pardoned 23 anti-abortion activists who were convicted under the FACE Act, many of whom are now pressing forward with efforts to continue to obstruct abortion services.

Julie Burkhart, the founder and president of Wellspring Health Access in Casper, Wyoming, is intimately familiar with what can happen if abortion opponents decide to take drastic action. An arsonist set fire to Wellspring, the only facility providing procedural and medication abortion in the state, weeks before it was scheduled to begin seeing patients in 2022. The damage to the building set back its opening by a year. The threat has not been eliminated: Burkhart said that she had been recently alerted to videos posted to social media “alluding to the fact that it wouldn’t be a bad idea if it were set on fire again.”

“It really sends, you know, a chill down all of our spines, because we don’t know who in law enforcement is going to have our back,” said Burkhart. “If, God forbid, there were a shooting, or an arson, or a place being flooded—any act of violence at a facility—we just don’t know who’s going to be there to respond and to help us.”

Without guarantee of federal response, Hayes is also concerned about how local law enforcement will engage. Despite spending several years building a relationship with city officials, the recent public struggles of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Police Department—including an ongoing audit of an alleged settlement with the police chief, who is now retiring at the end of the year—have left Hayes worried about the degree to which the department will be able to focus on threats to the clinic.

“It’s always just that much more frustrating when [protesters] do something, and maybe the cops do come and they ask them to stop, but there’s no no charges, there’s no accountability, there’s no nothing,” said Hayes. “You’re seeing this confusion about what to enforce and what not to enforce.”

Meanwhile, abortion opponents are urging local law enforcement to follow the federal government’s lead and stay out of their way. “If you’re a Christian police officer, a pro-life police officer, you need to commit in your heart not to arrest rescuers that are defending children, leave them be, even if it costs you your job. If you’re not willing to protect the children yourself, let us do it,” said Jonathan Darnel, one of the anti-abortion activists pardoned by Trump, in a recent online event.

Although the threats against clinics have yet to reach the apex of the anti-abortion demonstrations of the 1980s and 1990s, before the FACE Act was approved, providers warn that the current political environment could lead to a return to those conditions. A recent report published by the National Abortion Federation outlined thousands of incidents of violence and disruption against clinics in the years 2023 and 2024. This included 777 instances of obstruction of clinics, 621 instances of trespassing, 296 threats of death or harm to abortion providers and patients, and 128,570 protesters demonstrating outside of clinics over that two-year period. The report also noted that disruptions were likely being underreported, as clinics may not report all incidents, and not all abortion providers are members of NAF.

Providers are also wary about the growing prevalence of “abolitionist” sentiment among abortion opponents who believe that people who seek abortions should be criminally liable. While this notion is still on the fringes of anti-abortion politics, it has become increasingly acceptable among mainstream politicians, with more than a dozen bills introduced in state legislative sessions across the country to assign personhood to embryos. Although these measures are considered long shots for passage, providers worry that the Trump administration’s actions and the Dobbs decision have granted abolitionists a second wind.

“We’ve already talked to clinics in 2025 who have experienced increased hostility, higher numbers of protesters, and [are] really noting that it seems like the protesters have had a shift and are just emboldened and more aggressive and hostile under this administration,” said Melissa Fowler, the chief program officer at NAF.

Fowler noted that, in the wake of the Dobbs decision overturning Roe v. Wade, abortion opponents may travel to demonstrate at clinics in other states where the procedure remains legal. While 12 states have implemented a total ban on the procedure, there has been an increase in abortions since the Dobbs decision, in part because pregnant people seeking abortions will travel out of state. She also said that even in states where abortion is prohibited, clinics that provide other reproductive health services will still attract protesters.

“It really just shows, I think, that these protesters don’t really care about what they’re doing or the effect it has on people, and they really just continue to target anyone that walks into a facility,” Fowler argued.

Burkhart added that the worries about threats can be detrimental for both patients and clinic staff, which in turn can hamper their ability to provide care. “That psychological weight that people who work in the clinics carry, being yelled at and harassed going into a parking lot, that raises your heart rate. That’s a stressor,” she said.

Despite the potential risks and uncertainty, however, providers remain determined to offer abortion care, regardless of the political environment. Helen Weems, the owner of All Families Healthcare in Whitefish, Montana, said that her clinic was doing “everything we can to heighten our security and our vigilance.”

“We won’t be intimidated. We won’t be cowed into shutting down,” Weems said. “We will continue to show up for our patients, because the need continues unabated.”