Back in 1935, on the pages of The New Republic, the editors wrote that the United States was in desperate need of “a party with real possibilities of becoming powerful in elections in the not distant future, and devoted to the purpose of establishing collectivism so that the working masses may produce abundance for themselves.” Those words ring as true today as they did when they were first published 90 years ago.

You might have noticed the word “abundance” lurking on TNR’s pages lately. While abundance is all the rage as a political clarion call these days, its modern iteration is entirely disjointed from a long history of the word’s use on the left to call for a very different political program from the one imagined by current abundists like Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson. As Nima Shirazi and Adam Johnson discussed on their Citations Needed podcast, the term was long used in social justice circles as a foil for focusing on growth or wealth building. We should prioritize ensuring widely shared prosperity over the generation of new wealth, the argument went.

Last winter, I chanced upon a copy of The New Republic, Volume 83, from the summer of 1935 while doing some Christmas shopping in a neighborhood antiques store. As I perused the volume, I was struck by how often the word abundance was used to describe the purpose of a proposed new political party on the left. By this point, I had been following the rise of our modern abundance movement for the better part of two years. The abundance called for in the pages of TNR in 1935 is strikingly different from the abundance called for today by a loose coalition of (largely) centrist liberals and libertarians.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt has been frequently invoked by both proponents and critics of the abundance movement in recent months. Critics point to the New Deal as a paradigm that we should strive to replicate, where capital is disciplined, wealth redistributed, and direct government action used to build critical infrastructure the private sector won’t. Proponents retort that such public investment was only possible because of how many fewer bottlenecks to public policy existed during FDR’s time than do today and that the emphasis on disciplining capital belies a “monomaniacal” disdain for the private sector.

But that entire debate is tainted by a modern conception of Roosevelt as the left edge of the political system, whereas, at the time, many on the left were so unimpressed that they devoted a lot of ink to thoughts of launching a new political party on the Democrats’ left flank. The columnist Max Lerner summed up Roosevelt’s political program as “the middle road of the New Deal.” In fact, the editorial “Toward a New Party” noted, in May 1935, that “disappointment with the New Deal is growing just as rapidly on the Left as is opposition to its declared aims and measures on the Right.”

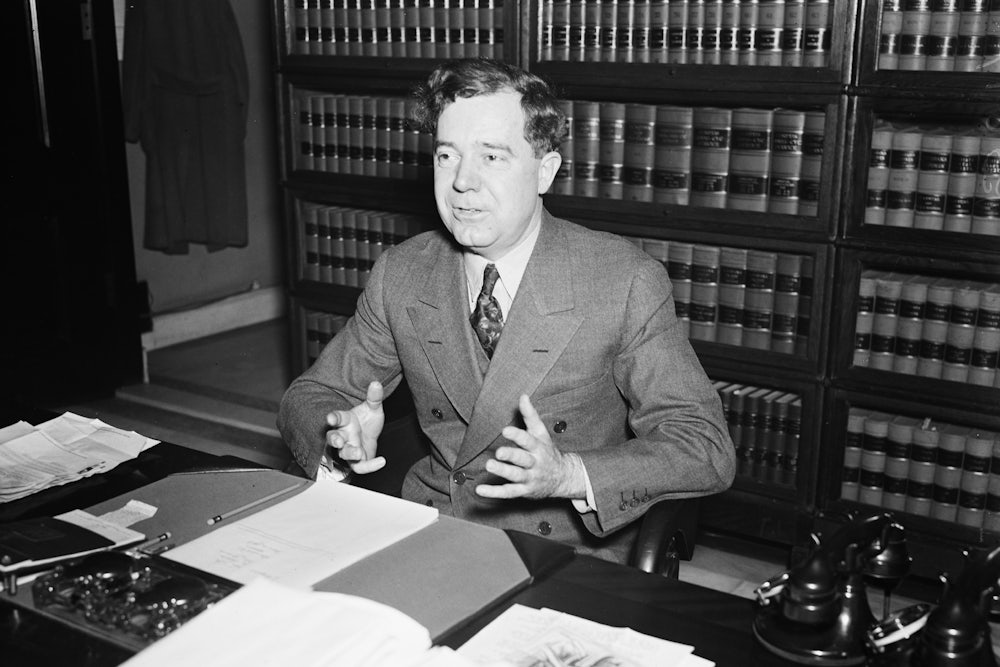

On April 29, 1935, Senator Huey Long, leader of the populist Share the Wealth campaign, headlined the annual conference of the National Farmers Holiday Association, whose president opened by “deprecating the reports that a third party was to be born that day.” Next came a priest who declared that Jesus had come “not only to save the souls of men, but also to introduce an economy of abundance.” The association’s president introduced Senator Long as God’s ordained champion, given to compensate the American people for “Roosevelt, [Secretary of Commerce Henry] Wallace, [Undersecretary of Agriculture Rexford] Tugwell, and the rest of the traitors.”

When Long took the stage, he called for capping the amount of wealth any individual could hold (at 300 times the mean level) and giving everyone a home and a guaranteed income reminiscent of modern universal basic income proposals. He asked the crowd, “Are you going to let a little bloated plutocracy control the United States government?” Where today’s abundance agenda’s champions evince skepticism of campaigning against “oligarchs,” the champions of abundance in 1935 were seeking a showdown with them. (Long’s populism, however, should be viewed with skepticism; while railing against a parasitic elite, he helmed a political machine that had violently overthrown the Reconstruction-era state government and was no stranger to political cronyism.)

“A new party is in the air,” declared the May 22, 1935, issue of The New Republic. “It seems to be the logical sequence to the independent success of the La Follettes in Wisconsin, of the Farmer-Laborites in Minnesota, of various movements in industrial regions.”

While Long was the central figure in speculation of a left third party, he was not alone. Other prominent politicians and activists in this loose abundance faction included New York City Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, Wisconsin Governor Philip La Follette, Minnesota Governor Floyd Olson, Wisconsin Senator Robert La Follette (Philip’s brother), Montana Senator Gerald Nye, and Father Coughlin.

That sundry group boasted an array of political affiliations. Olson was the figurehead of Minnesota’s Farmer-Labor Party (a direct ancestor of the state’s current Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party). The La Follettes and their political machine were the engine of Wisconsin’s Progressive Party. La Guardia and Gerald Nye were prominent progressive Republicans. The singular Huey Long branded himself as a populist Democrat.

The “left” in 1935 was very different from today’s version. In particular, while the figures discussed here were all avowed (at least facially) economic populists, several would be persona non grata (properly; yes, some “purity tests” are warranted) in the modern progressive movement, particularly for their views on racial issues. Father Coughlin would, just a few years on from the events detailed herein, go on to air vile antisemitism on his radio program and voice support for the Nazi government. Farmer-Labor Senator Henrik Shipstead was also a noted antisemite. Even La Guardia, among the most sympathetic of the bunch to a modern audience, helped raise funds to support the invasion of Ethiopia by fascist Italy.

Long, in particular, had several closetfuls of skeletons that run counter to his professed “man of the people” persona. John Ganz has an account of some of Long’s most notable sins; he opposed a federal anti-lynching measure, killed a pension plan because too much money would go to Black recipients, and imposed martial law to help secure a contested election.

Even while The New Republic was making the case for its third party, its writers were not particularly enthused by Long so much as begrudgingly accepting of him as an element of the economic populist left. In the June 5, 1935, issue, the editors express exasperation at Long getting his own law firm placed in charge of state tax collection. In the weekly dispatches at the top of the issue, TNR laid into the Louisiana Democrat, sarcastically writing, “Yea, verily, the wealth must be shared.”

This new leftist third party was to be based in the “American tradition of democracy and equality,” particularly with respect to democratizing economic life. The TNR editors argued, “We have lost—indeed, for the most part, have never exercised—the right of democratic control of our economic lives.”

This party’s fundamental purpose was “to arrange industry so that it may produce the abundance it is technically capable of producing, and thus may provide material security for all.” The editors continue:

What we want is an economy planned to produce abundance. That implies an industrial system operating according to a social plan, a plan that visualizes in advance the amount of production and employment, the wage policies and price policies, the interrelationships among industries and financial institutions. The very reason we need collective ownership is that private industry cannot and will not operate according to such a plan.

Talk of a socialist or leftist political party was nothing new in the 1930s. The United States is actually rather odd historically (among Western nations that industrialized early) for not having a prominent labor/socialist party that rose to prominence following industrialization. Most peer nations saw insurgent left factions in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, often displacing more mainline liberal factions. In perhaps the most intuitive example, the British Liberal Party collapsed spectacularly in 1924 after being the ruling party for most of the previous two decades, with an ascendant Labour Party displacing it.

But in early July 1935, a convention in Chicago sketched out what a new party could look like and what its founding principles would be. The final platform had 14 planks, some of which appealed to an economy of abundance. For instance:

Plank 1: “As a means to transition to an economy of abundance we favor unlimited production for use by and for the unemployed.”

Plank 3: “We declare for complete economic security for all through abundant provision for needs and emergencies such as maternity, infancy, education, sickness, accident, old age, and unemployment.”

Even in those invocations of abundance, the stark differences between the socialist abundance movement of 1935 and the moderate abundance agenda of 2025 are apparent. The concept of “production for use” is in contrast to the capitalist profit motive. In socialist thought, one of the core issues of a capitalist economy is that profit motives result in wealth accumulation becoming divorced from the creation of actual economic value. A production for use system makes production and allocation decisions based on need (or “use value”), rather than market prices.

Note, also, the call for “abundant provision.” Where Klein, Thompson, and company argue that the center-left must reorient its focus away from welfare state–style programs and toward policies that boost supply and growth, the socialist abundists pointed to such mechanisms as the central pillar of shared prosperity.

In case the point was not quite clear, the platform stated in its tenth plank, “We favor immediate public ownership and operation of natural resources, transportation and communication, public utilities, mines, munitions plants and basic industry.”

To The New Republic editors, this collectivist faction that championed an economy of abundance was the “true opposition” to Franklin Roosevelt’s ruling coalition. In Congress, this left opposition included several dozen members of the House of Representatives, collectively called “the Mavericks” after Representative Maury Maverick (whose grandfather, Samuel, is where we get the term maverick, after the cattle he left unbranded). In the Senate, the left featured figures like Robert La Follette, Henrik Shipstead, and, of course, Huey Long.

Despite efforts to coalesce all of these various figures and movements into a durable left party proving abortive, the summer of 1935 saw an energized left, fed up with Roosevelt being insufficiently radical and invigorated by widespread labor and political organizing.

Robert Cantwell, in the May 22 issue, wrote of the turnaround for the left in California, which in recent months had seen an “astonishing and heartening” transformation from being in full political retreat to being energized, organized, and mobilized. Cantwell attributes the reversal to Upton Sinclair’s gubernatorial campaign. Sinclair, a long-standing socialist best known as author of The Jungle, ran on the Democratic Party platform for his third attempt. While he didn’t prevail (and faced backlash from the Socialist Party), the campaign got over 800,000 votes and saw volunteers mobilized in numbers greater than the Democratic Party infrastructure was able to coordinate. The experience resulted in “an enlightened, disillusioned, politically experienced electorate.”

Sinclair fell short, but many other left-wing collectivists were winning across the United States. Progressive Republicans from northern states like La Guardia and Nye, populist Democrats (following the legacy of William Jennings Bryan) like Maverick and Long, and Midwestern third-party collectivists like Olson and the La Follettes parlayed similar tactics and grassroots support into electoral wins.

The abundance movement of 1935 may not have had a party line or formal infrastructure, but it had a strong electoral track record, a strong popular base of support, and a well-defined platform.

The left-abundance party did not come to fruition, through a combination of historical unpredictabilities and well-known problems.

Even as they were writing in support of the new party in these pages, The New Republic’s editors were acutely aware of the obstacles it faced. For a start, while the rank and file of progressive and labor groups were agitating for the third party, the abundance politicians were far more hesitant. Some of this was because figures like La Guardia, Olson, and Phil La Follette had a strong incentive to stay on Roosevelt’s good side, as they needed federal aid money for their states (or city, in La Guardia’s case). Governor La Follette explicitly came out in opposition to a left third-party challenge in the 1936 election.

But it was the assassination of Senator Huey Long that buried the idea of mounting a serious challenge to FDR from the left in the 1936 election. Long’s death made a daunting prospect harder. And with one of the most vocal potential rivals within the Democratic Party silenced, it strengthened Roosevelt’s position.

And while Coughlin’s National Union for Social Justice did form the Union Party, it proved to be a nonfactor beyond denting Roosevelt’s vote share in the 1936 election. Following FDR’s reelection, both the NUSJ and the Union Party disbanded.

It is ironic that the modern abundance movement is animated by many of the things that the original abundance faction detested. Huey Long called for eliminating oligarchs, while the new abundance movement is funded by them. A key tenet of Klein and Thompson’s approach is to reorient left-of-center politics away from redistribution to create abundance. In the 1935 telling, redistribution was the mechanism of abundance. The 1935 abundance faction was ardently populist—Governor Olson once threatened to invoke martial law to forcibly seize and reallocate wealth—while our current version is specifically intended to combat populism.

In the June 12, 1935, issue, John T. Flynn lambasted the National Recovery Administration as a means of empowering business interests under “pretenses of a great liberal movement.” There is no better articulation of why critics on the left distrust Klein’s movement than that it is a front for monied interests—with the facade of a great liberal movement.