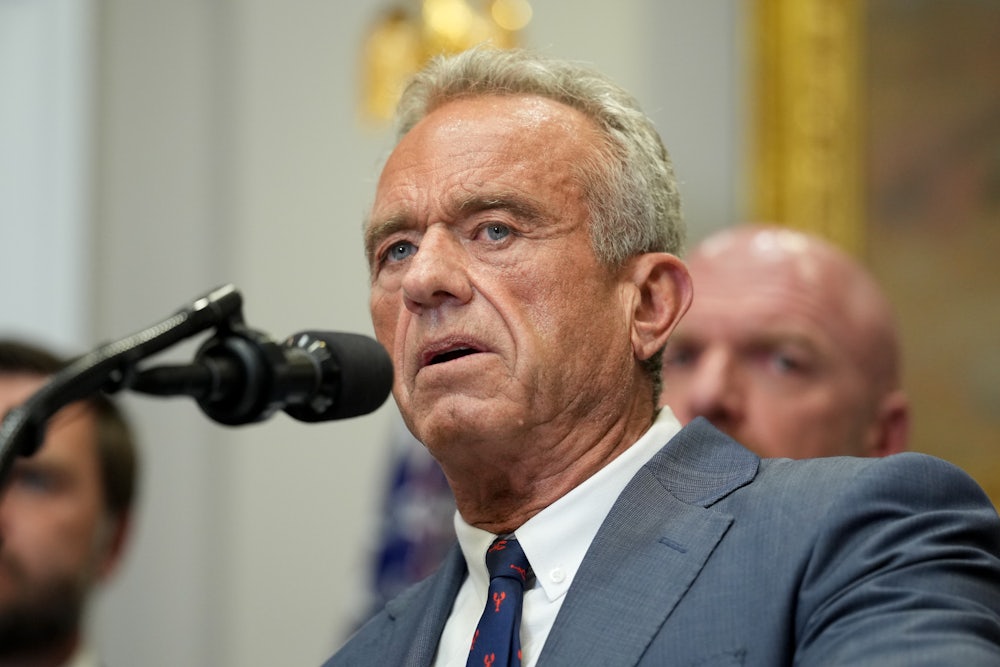

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has made targeting ultraprocessed foods a centerpiece of his “Make America Healthy Again” agenda, working to limit access to the items he has called “poison.” But efforts by the Trump administration to further define and limit access to ultraprocessed foods may not only be difficult to accomplish, they could also have larger implications for low-income families.

In May, Kennedy’s Department of Health and Human Services released a report singling out ultraprocessed foods as a cause of the “chronic disease crisis” among children. This report included several fake citations, although the sections related to ultraprocessed foods appear to be backed by accurate sources and were praised by researchers for identifying the food industry as a culprit in children’s poor health.

Ultraprocessed foods, which are industrially produced foods containing processed ingredients, have been connected to a host of health conditions, such as diabetes, obesity, and heart disease. They are also a significant part of the American diet: More than two-thirds of calories consumed by American youth are from ultraprocessed foods. Moreover, ultraprocessed foods comprise the majority of all calories consumed by Americans overall, according to a report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released on Thursday that is in line with previous research on the topic.

Public health experts have long argued in favor of limiting access to ultraprocessed foods, citing the negative health outcomes that come from consumption of these items. Low-income Americans may be particularly vulnerable; one recent study found that participants in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, formerly known as food stamps, consume ultraprocessed foods at a higher rate than other Americans. As children in these households are more likely to consume ultraprocessed foods than their higher-income peers—and experience greater rates of obesity, which is associated with poor health—some experts have argued in favor of limiting access to these foods in SNAP.

It seems that they’ve found a sympathetic ear in the Trump administration. As of this week, 12 states have been approved for waivers to restrict SNAP benefits from being used to purchase certain ultraprocessed foods and drinks. Depending on the state, these restrictions may apply to soft drinks, energy drinks, candy, and in the case of Arkansas, fruit and vegetable drinks with less than 50 percent natural juice.

“These waivers help put real food back at the center of the program and empower states to lead the charge in protecting public health. I thank these governors who have stepped up to request waivers, and I encourage others to follow their lead. This is how we Make America Healthy Again,” Kennedy said on Monday.

Last month, the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Food and Drug Administration submitted a joint Request for Information to “gather information and data to help establish a federally recognized uniform definition” for ultraprocessed foods, to “allow for consistency in research and policy to pave the way for addressing health concerns” associated with their consumption.

Most research into the effects of ultraprocessed foods uses the Nova classification system, which was developed by scientists in Brazil. But some critics argue that this system focuses on the level of processing that an item undergoes, rather than looking at the nutritional value. Food and Drug Administration commissioner Marty Makary acknowledged in a recent interview with Politico that “maybe we won’t get it right on the first definition—because there’s no perfect definition.” Makary added that there would be “implications” for programs like free school meals and SNAP.

“When we are using taxpayer dollars, we’ve got to make better decisions,” he said.

But creating a unified definition for ultraprocessed foods may be a difficult endeavor. Certain foods, such as potato chips and frozen meals, are easy to identify as ultraprocessed. But other ultraprocessed foods include commercial whole wheat bread and flavored yogurts, items that might be considered “healthy” at first blush.

“The question is, how do you come up with a definition that casts a wide enough tent to include the major junk foods in American diets but excludes foods that really would be OK for people to eat?” said Marion Nestle, a professor emerita at New York University and author of the book Food Politics. Moreover, the USDA has lost roughly 15,000 employees over the past six months, through cuts and people leaving the agency, which could further complicate the issue. Additionally, there are personnel fears about censorship: Even though the May report issued by HHS heavily cites the work of Kevin Hall on ultraprocessed foods, Hall left the National Institutes of Health in April, saying his research had been “hobbled” by the Trump administration.

There are arguments that limiting access to ultraprocessed foods could be difficult for low-income households, as they need to have the necessary equipment for cooking—for example, an oven, a refrigerator, and pots and pans. However, if poor Americans do have access to these items, cooking should not be as much of a burden, said Nestle.

“If you know how to cook, you can eat real food and do pretty well at a much lower cost,” she said. Moreover, Nestle noted that states are currently focused on barring access to sugar-sweetened beverages and candy, rather than all ultraprocessed foods—items that are “easy targets,” she said. But there does not appear to be any accompanying research by states into whether these limits will actually lower purchase of sodas and candy by SNAP households, she continued, or whether it will reduce participation in SNAP overall.

Then there is the question of political intent. Previous administrations have worried that limiting access to certain foods through SNAP could be considered “overly paternalistic,” said Parker Wilde, a food economist and professor at the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University. SNAP participants have very similar food purchasing patterns to non-SNAP households, but only these low-income families are having their choices limited. Other experts have argued there are logistical challenges in barring certain foods and beverages. In 2010, then–Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack denied a waiver request from New York City to ban access to soda through SNAP. (Vilsack himself has argued that it is preferable to incentivize healthier eating rather than limiting access to certain foods and beverages.)

There may be health benefits to barring certain foods and drinks from being purchased with SNAP benefits. But when those policies are accompanied by cuts to SNAP, they are less about serving the interests of low-income Americans and more about making their lives more difficult, argued Wilde. Since President Donald Trump took office, the USDA has cut programs that provide funding for local food charities and school meals, as well as dramatically slashing the Emergency Food Assistance Program. Moreover, the recent spending law passed by Congress would massively cut SNAP, potentially removing millions of people from the program. Within that larger political context, the emphasis on limiting access to ultraprocessed foods for low-income Americans seems more targeted, said Wilde.

“The current political environment that supports these restrictions is essentially a coalition of MAHA themes, which are uncertain about processed food and unhealthy food, and anti–safety net themes, which are longer-standing Republican objectives,” he said. With the exception of Colorado, each of the states that have received waivers to limit access to certain foods and beverages through SNAP are led by Republican governors.

Wilde argued that the current efforts were not paternalistic because “paternalism implies trying to serve the interests of the participants in the program.”

“But if you’re cutting benefits at the same time, that’s not paternalism, that’s harm,” he said.