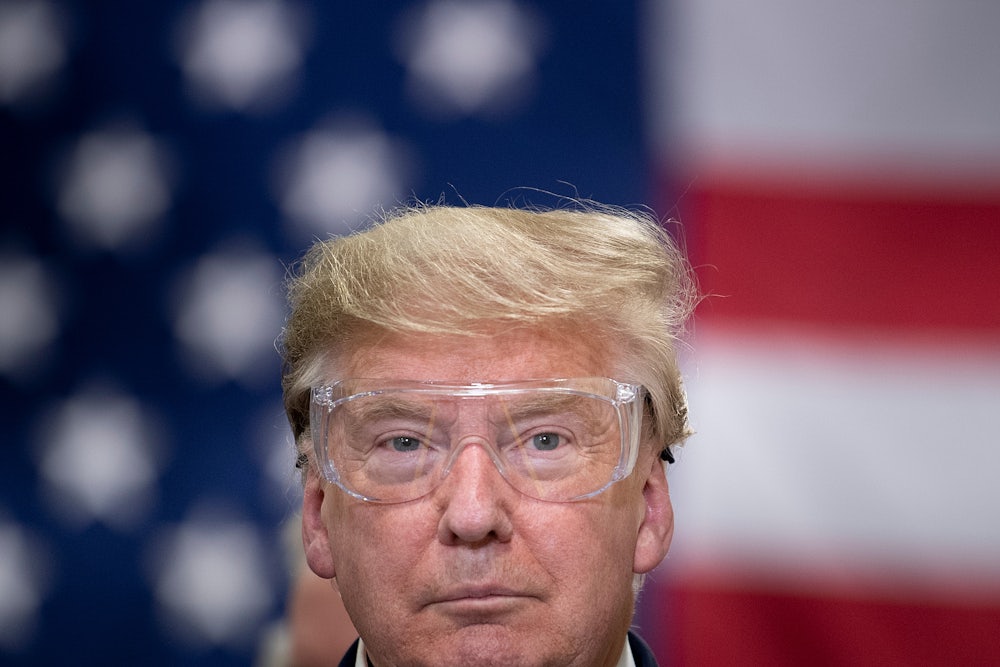

When Donald Trump announced that the federal government would take a 10 percent equity stake in the tech company and chip manufacturer Intel, the reaction was swift, predictable, and bipartisan. Senators Rand Paul, Kentucky Republican, and Greg Stanton, a Democrat from Arizona, both referenced a slide toward socialism. Governor Gavin Newsom’s press office shared an AI-generated image on X of Trump in front of a communist flag, writing “ALL HAIL CHAIRMAN TRUMP! WITH HIS GLORIOUS 10% PURCHASE OF INTEL, THE SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF AMERICA ENTERS A BOLD NEW ERA OF GOVERNMENT-RUN BUSINESS.”

A piece from the libertarian CATO Institute noted that “Industrial Policy [is] the Gateway Drug to Cronyism.” Oregon Democratic Senator Ron Wyden called the arrangement “nothing more than corporate extortion,” while Rep. Daniel Goldman of New York described it as a shakedown that wouldn’t end at Intel. My colleague Tim Noah called the move a form of “fascist corporatism.”

Trump, characteristically undeterred, said he hopes to see “many more cases like it.”

The responses capture the ideological confusion of this moment. Critics from across the political spectrum were quick to paint the arrangement as socialism. Senator Bernie Sanders—who’s long been a proponent of public ownership in large corporations—was among the few who praised the deal, pointing out that he had introduced a similar amendment during debate over the CHIPS and Science Act, which was signed into law under Joe Biden. (Trump was able to secure the government’s stake in Intel in part by withholding billions in funds designated for Intel in the CHIPS Act.)

Calling this socialism, however, misses the mark widely. What Trump embraced when he declared the move necessary to ensure America’s national security and economic competitiveness, was not worker ownership or democratic control of the means of production, but state capitalism. Greg Ip of The Wall Street Journal argued that Trump’s strategy resembled the Chinese model, dubbing it “state capitalism with American characteristics.” The American Prospect labeled it “Trumpian” state capitalism.

Still, what matters most here is not the terminology but the precedent. The Intel deal should be treated not as a scandal, but as a shift in America’s approach to capitalism—one that could serve Trump’s cronyism or, if the left seizes it, a more democratic vision of public ownership and global competitiveness.

For decades, the idea that the federal government could take equity stakes in private corporations has been treated as taboo, a vestige of Cold War suspicion of anything resembling public ownership. But it isn’t without precedent in American life: During World War II mobilization, Washington didn’t hesitate to take direct stakes in and direction over key industries; public ownership has long been part of the U.S. toolkit when national security was at stake. The 2008 financial crisis saw the government take temporary stakes in GM, Citigroup, and AIG. The Covid-19 pandemic involved massive public subsidies to airlines and small businesses and the invocation of the 1950 Defense Production Act to direct companies to manufacture devices like masks and ventilators. Now, with Intel, the U.S. has crossed another threshold by not just stabilizing or commanding companies in crisis but investing directly in their future.

Intel is not the only company being targeted for government ownership. As part of an unprecedented deal, chipmakers Nvidia and AMD will now turn over 15 percent of their revenue from sales in China. In July, the Pentagon became the largest shareholder in MP Materials, the country’s only operational rare earth mine. A month earlier, the U.S. secured a “golden share” in U.S. Steel as part of its $15 billion takeover by Japan’s Nippon Steel, giving Washington the right to appoint an independent director to the company’s board.

On Tuesday, Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick suggested the administration might extend the Intel model to defense contractors. In an interview with CNBC’s “Squawk Box,” he noted that Lockheed Martin earns 97 percent of its revenue from the federal government. The company, he said, was “basically an arm of the U.S. government.” The way munitions have historically been financed, he added, has amounted to a “giveaway.”

Industrial policy is no longer a fringe idea: It was a key component of Biden’s presidency and one that was widely praised by policy experts. It is here to stay. The only question is who will benefit from it.

By simply condemning the Intel deal, liberals and progressives risk ceding the ground to the right by allowing conservatives to dictate the narrative. Democrats too often play defense, backing off at the first cry of “socialism.” They should go on offense, argue plainly that public investment deserves public return, and that government power can serve the common good.

As commentator Krystal Ball recently put it on Breaking Points, “I hope there’s some bold Democrat out there somewhere who’s looking at all of this [and saying] okay, they’ve laid down the marker here. We can take this model and expand it and actually do it in the American interest.”

For decades, the United States has socialized the risks of private enterprise while privatizing the rewards. We’ve showered corporations with subsidies and tax breaks and bailed them out when they’ve failed while rarely asking for much—or sometimes anything—in return. If taxpayer money is going to prop up private firms, as it has for decades, then taxpayers deserve a share of the gains, too.

Even if it takes Trump, like a broken clock, to stumble into the point, the underlying principle is sound: The government should hold equity in more of corporate America, not less. Other nations already do this. Norway’s sovereign wealth fund owns shares in thousands of companies worldwide. China’s sovereign wealth fund, the China Investment Corporation, manages over a trillion dollars in assets worldwide, making it one of the largest state investors in global markets. Saudi Arabia’s Private Investment Fund is a key part of its foreign policy. Kevin Hassett, director of the National Economic Council, has suggested that the United States establish a sovereign wealth fund. Democrats should be taking notes. The United States, by contrast, has been content to subsidize corporate America without demanding ownership in return.

Nowhere is the case for public ownership clearer than in the defense sector. Lutnick—like Trump, a broken clock—was right when he said that companies like Lockheed Martin already function as quasi-public entities, deriving nearly all their revenue from government contracts. They are, in effect, state enterprises run for private profit.

The same logic applies, more urgently still, to fossil fuels. Oil and gas companies are huge recipients of public support in the form of subsidies, tax breaks, and infrastructure guarantees. Their core incentive is to extract and burn as much carbon as humanly possible. No serious observer still believes the free market can manage the climate crisis. Nationalization would not only ensure that the vast sums of public money already flowing into fossil fuels yields a return for taxpayers. It would also make possible a managed and just transition away from carbon. Norway’s state-owned oil company has demonstrated that public ownership is not only feasible but profitable.

Pharmaceuticals form the third pillar of this argument. All three are life-or-death domains where markets consistently fail people with fatal consequences. The industry’s most profitable products are overwhelmingly built on the back of publicly funded research, much of it financed by the National Institutes of Health. Between 2010 and 2019, every single one of the 356 new drugs approved by the FDA traced its origins to NIH-funded science, according to a 2020 paper by the Institute for New Economic Thinking. Yet the profits accrue almost entirely to private firms, who charge the public exorbitant prices for medicines that it effectively paid to invent. (Trump, meanwhile, has cut nearly $2 billion in research grants to the NIH, gutting the very research pipeline that makes these breakthroughs possible.) Taxpayers finance the breakthroughs, but then are forced to buy them back at inflated prices, often at the cost of debt or denied care.

Taken together, defense, energy, and medicine are the three pillars of a secure society. All are already heavily subsidized, propped up, and protected by the state. The question is not whether governments will be involved but whether that involvement will continue to serve shareholders or be redirected toward a more livable future.

Trump’s Intel spectacle may fade from the headlines, but the larger lesson should not. Government intervention is already a fact of American capitalism. The issue is whether we continue to accept a system in which corporations feast at the public trough without giving anything back, or whether we move toward a model in which taxpayers are not only investors but stakeholders, beneficiaries, and decision-makers.

The neoliberal era insisted that markets knew best and the government’s role was to step aside. That consensus has collapsed. Industrial policy has returned. The choice now is between a corporate-led version that socializes losses while privatizing gains, or a democratic version that ensures public investments yield public returns.

Trump may be pursuing this for all the wrong reasons—cronyism, control, or just plain spectacle—but the move nonetheless cracks open a door others should be ready to walk through. If the left seizes this moment, it can help build a new common sense: one in which public money buys public power, and ownership becomes the foundation for a more equitable, sustainable economy. If it fails, Trump and his allies will be more than happy to define state capitalism on their own terms.