In February 2014, veteran journalist Bill Keller announced that he was leaving The New York Times, where he had worked for three decades, to helm a new nonprofit newsroom focused on criminal justice. As founding editor in chief of The Marshall Project, Keller said he sought to produce journalism that would provide “a bit of a wake-up call to a public that has gotten a little numbed to the scandal that our criminal justice system is.” The publication launched in November 2014 with a two-part feature on 80 death-row inmates whose lawyers missed a crucial deadline to file last-resort federal habeas corpus petitions. Though the investigation, by Ken Armstrong, employed individual men’s stories to hammer home the stakes, its focus was the intersection of two systemic faults—an “unforgiving” law signed by President Bill Clinton that set a one-year deadline for people condemned to death to file habeas petitions and the “lack of oversight and accountability” for incompetent lawyers who miss the deadline.

That same month, millions were tuning in to the first season of Serial, a 12-part podcast series unraveling the case of Hae Min Lee, a high school senior in Baltimore County, Maryland, who was killed in 1999. Her ex-boyfriend Adnan Syed was convicted of her murder in 2000 and sentenced to life in prison. The series was sparked by Syed’s claim of innocence, and the narrative was strictly focused on whether this particular man ought to have been convicted of this particular crime.

In an interview with Vox at the time, Keller said that the entire newsroom was obsessed with Serial. But, he said, “I don’t look at Serial as a sort of reflection on the state of the criminal justice system, or the state of public support for criminal justice reform. It’s just a really well done mystery story.”

In turning the story of a 15-year-old murder into a high-gloss mystery, Serial launched a new era of true crime, coating morbid entertainment with an intellectually serious veneer. But where The Marshall Project prods readers to confront a fundamentally broken criminal legal system, rarely does even the most nuanced and rigorous true crime push the consumer to reflect on how the case under consideration intersects with wider issues. And along with prestige TV offerings like Netflix’s Making a Murderer and HBO’s The Jinx came a barrage of slop. In 2017, the cable channel Oxygen pivoted to offering 24/7 true crime, sating viewers’ appetites for sensational stories of humanity at its most gruesome. Current programming includes Buried in the Backyard (“stories of homicide victims left hidden underground in idyllic places”).

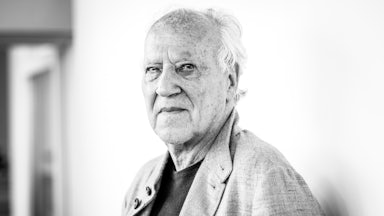

For Marshall Project contributing writer John J. Lennon, the public’s hunger for true crime raises urgent questions: “What are the consequences of illuminating human darkness? Does it increase our desire for punishment? Does true crime hinder the progress of criminal justice writers and activists and reformers and policymakers?” This line of inquiry is personal, as Lennon explores in The Tragedy of True Crime: Four Guilty Men and the Stories that Define Us; depending on how you tell his story, he is either an irredeemably evil murderer or a man capable of genuine remorse and reinvention.

In December 2001, when he was 24, Lennon murdered a friend and fellow drug dealer who was rumored to be robbing other dealers. They had grown up in the same Brooklyn project in the late 1970s and early 1980s; Lennon is white, his victim Black. In his book, Lennon explains both his mindset at the time and his current perspective: “I told myself that killing him was the only solution. (This is the absurdity of the drug game: We betray and kill our friends).” He also realizes now that he was not influenced solely by drug-game logic. “I feared others would learn about things I did that conflicted with who I wanted to be in ‘the life,’” Lennon writes. “Many of us who commit terrible violence struggle internally with something that guts us hollow.” Across The Tragedy of True Crime, he identifies fear as the catalyst of his violence.

When he was charged for the killing in early 2002, Lennon was already in jail at Rikers Island for gun possession and selling heroin. Two years later, he was found guilty of second-degree murder and sentenced to 28 years to life in prison. It would take years for Lennon to begin to understand why he committed such terrible acts. “Deep reflection can only arrive, if it ever does, when you feel removed enough from all the madness, from the version of yourself that you once were,” he explains. “And sometimes that takes years, because after the crime comes the arrest, the jail time, the trials, and prison—watching television in the cellblock or getting high with the guys in the yard, telling one another how the system fucked each of us respectively.”

For Lennon, it was a creative writing workshop that he fought to get into in Attica in 2010—along with twice-weekly Alcoholics Anonymous meetings—that pushed him out of the numbing so common in prison and toward cultivating reflection and remorse. He has since become a leading prison journalist, writing for outlets like The New Yorker, The New York Review of Books, and Esquire, where he is a contributing editor. In his book, Lennon weaves reflections on his own past, crime, and time in prison throughout the stories of three other men guilty of taking a life, whom he has served alongside in New York prisons. With his personal reflections, he writes, he hopes to “explain why people like me do what we did.” He has come to this insight in large part despite being on his twenty-fourth year in prison, which is not an environment that fosters deep thinking. It is Lennon’s writing career, eked out under extraordinary circumstances and with the assistance of many editors and writers on the outside, that has allowed him to explore his guilt and, as he writes, “develop more of the thing I’ve always lacked: empathy.” That empathy allows him to “offer the felt lives of men who have taken a life … to show you who we are, hopefully without diminishing the lives of the people we’ve killed,” in The Tragedy of True Crime.

Lennon uses his incomparable access to fellow incarcerated men to highlight the context behind their crimes and to paint portraits of how prison changed them, but he does not excuse their killings—or his own. Most sympathetic is Michael Shane Hale, a white gay man from Kentucky, who was 23 in 1995 when, after years of being controlled, physically and sexual abused, and harassed, he murdered his 62-year-old partner, Stefan Tanner. On the night he killed Tanner, Hale was trying to collect his belongings and leave Tanner’s Brooklyn apartment when Tanner called 911 and falsely claimed he was being attacked. The NYPD officers who answered the call declined to file a domestic incident report. Later that night, Hale returned to the building to retrieve the rest of his clothes and confront Tanner. The two got into a physical fight in the garage and Tanner died after Hale knocked his head repeatedly on the concrete floor. Hale immediately expressed remorse.

Lennon’s other two subjects—Milton E. Jones, a Black man convicted of murdering two priests in Buffalo, New York, in 1987 at age 17, and Robert Chambers, the notorious “Preppy Killer,” who killed 18-year-old Jennifer Levin in Central Park in 1986—are more challenging. Jones killed the priests alongside a friend from juvenile detention who suggested they rob rectories; Jones was a “follower,” whose biggest role models were his uncles—two pimps and a drug dealer. Lennon writes of learning of Jones’s crime before getting to know him, in a passage that preempts the reader’s response: “Milton’s laugh was loud and jolly, but it sounded almost filthy to me. When you learn about the crime before you meet the person, it makes you recoil; it colors everything about them.”

Of course, in true crime, the crime always precedes the perpetrator. In 2020, Lennon watched the docuseries The Preppy Murder: Death in Central Park on A&E in Sing Sing—inmates pay for cable through fundraisers, and true crime is popular in prisons too, where it provides both entertainment and intel on peers’ crimes. A few months later, he transferred to Sullivan and met Chambers, who was back in prison for drug charges years after completing his original 15-year bid for manslaughter. Chambers’s continuing resistance to admitting his full culpability for strangling Levin when he was 19 frustrates Lennon. “You already did the time,” he challenges Chambers. “Why not just cop to it?”

Lennon forces readers to consider the consequences of our current system of punishment and what it might mean to allow admitted violent criminals to be given second chances. Though Chambers struggled to take accountability for his guilt, he kept busy in Sullivan, working as a sign language interpreter for his peers and doing his best to avoid the unrelenting press interest in his case. “His life has become a public spectacle,” Lennon asserts, “and the narrative about him has grown so large it has outstripped any sense of self.”

Hale, serving a sentence of 50 years to life in Sing Sing, has carved a meaningful existence for himself there, serving as an inmate program assistant in a reentry facilitation program, though he fears he will die in prison. He has earned a master’s degree from the New York Theological Seminary and participates in a theater group, a competitive-to-access program funded by philanthropy, not the state or federal government. Jones, also serving 50 years to life in Sing Sing, has similarly managed to complete a theological master’s degree, despite a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, which has waxed and waned throughout his time in prison and has rarely been adequately treated. Both Hale and Jones have directly expressed their remorse to their victims’ families. Through these men’s stories and Lennon’s own, The Tragedy of True Crime provides a challenging and bracing reckoning with guilt and the possibility of changing the narrative of one’s life.

Some readers will immediately dismiss The Tragedy of True Crime. After all, what does it mean when the murderer is the journalist, telling fellow murderers’ stories? Lennon brings such critiques to the surface throughout the book. The epigraph for his first section comes from Janet Malcolm’s The Journalist and the Murderer, a study of journalistic ethics through the case of bestselling true crime writer Joe McGinnis: “The characters of nonfiction, no less than those of fiction, derive from the writer’s most idiosyncratic desires and deepest anxieties; they are what the writer wishes he was and worries he is.” Lennon sees something of himself in each of his subjects, and he is not afraid of laying bare his most unappealing traits and behaviors. “While journalism pushes me to feel deeply for others, I’m still self-absorbed and coarse,” he writes. “Cells will open, and I’ll say hello to my neighbor one day, then walk right by him the next.… My lip will snarl a bit when I hear something I don’t like.”

It is this honest self-reckoning, along with Lennon’s intimate, deeply reported treatments of his subjects’ stories, that makes The Tragedy of True Crime an indispensable addition to the recent literature of incarceration that kicked off with Michelle Alexander’s 2010 The New Jim Crow. While Alexander’s book and the titles that followed—including Bryan Stevenson’s Just Mercy and Ben Austen’s Correction—have offered insight into the foundations and consequences of mass incarceration and mandatory sentencing laws, The Tragedy of True Crime plunges the reader into the lived reality of incarceration and guilt for violent crime.

At its best, life in prison is monotonous. Lennon describes his daily routine of waking up with the 6:30 a.m. “count” (when correction officers account for the location of each inmate), brewing coffee through a homemade strainer, reading “Daily Reflections” from A.A., and getting to work on his writing before walking laps around the yard in the afternoon. But Lennon’s relative peace is fragile. He writes about his cell’s electricity being cut before C.O.s rifle through his belongings in search of contraband—iPhones, “exotic weed,” and heroin, which C.O.s themselves allow into prison—and being faulted for being over the “book limit.” And life inside was once far more dangerous for Lennon, even though as a drug dealer he was at the top of the “prison pecking order.” In 2009, a friend of his victim stabbed him six times in the chest with an ice pick in the yard at Green Haven prison, and he was transferred to Attica, “the worst prison in New York,” for refusing to identify the perpetrator.

Lennon connects his subjects’ stories to the larger forces shaping their crimes and their sentences, without ever losing sight of their individual culpability. Hale was routinely sexually abused as a boy growing up in Appalachia, and though Tanner began sexually assaulting and trafficking him early in their relationship, Tanner was the first and only person to make Hale feel “worthy of love.” The district attorney sought the death penalty in his case—for the first time since its reinstatement in New York in 1995—rejecting the defense’s argument that Hale’s case was a domestic tragedy. Hale is currently seeking post-conviction relief under the Domestic Violence Survivor’s Justice Act, which passed in New York in 2019 and allows judges to resentence offenders who demonstrate that their abuse was a “significant contributing factor” to their crime.

Jones is part of an overrepresented demographic in prison—as Lennon points out, prisons have become “America’s de facto asylums” in the aftermath of the 1960s movement against institutionalization. Jones also represents the generational trauma of incarceration in Black families—when he was a toddler, his father was in Attica on a robbery bid and was injured in the notorious 1971 Attica Uprising. Chambers, who started using drugs as a teenager in boarding school, has been in active addiction for much of his life and used heroin throughout his first stint in prison. Lennon, who admits to using dope in prison, understands its numbing appeal. “You don’t know what to do with your crime,” he writes. “Your future is lost. You’re miserable and fearful. So you do dope.”

At times, Lennon sacrifices depth for breadth—The Tragedy of True Crime is a near-encyclopedic window into life for men behind bars, touching on everything from conjugal visits to the politics of communal showers to the distinction between being placed in voluntary or involuntary protective custody. This blow-by-blow, though revelatory, at times interrupts the opportunity for sustained analysis of policies, like the 1994 crime bill, that have negatively impacted nearly every aspect of incarceration, from lengthening sentences to defunding higher education in prisons.

Though Lennon, Hale, and Jones have managed “to find a sliver of rehabilitation” through educational programs, their cases are exceptional. In one of the book’s most eye-opening passages, Lennon argues that the punishments of prison land harder on those who have managed to cultivate remorse—a rare feat, in his telling. “When I started writing, thinking deeper and feeling genuine remorse for killing E., the time in prison got harder,” Lennon writes. “Maybe it’s because I was becoming a better man. The more you strive to be decent in prison, the more you see and feel the cruelty of it.”

It is in these moments of reflection that Lennon illuminates the most disturbing parts of our culture’s obsession with true crime. True crime, he argues, “turns back the clock and replays the worst moments of someone’s life, reconstructs and reenacts it all for entertainment, usually by exploiting the people most affected by the violence—victims whose wounds haven’t healed, perpetrators who haven’t reckoned with their guilt.” In constantly reprising what cannot be changed—the violent crime—these narratives justify the punishment and lack of rehabilitative measures for people who can change—violent criminals. We live in a culture where people lull themselves to sleep with true crime stories of good versus evil droning out on their televisions.

Lennon believes that one such story is keeping him in prison. In 2019, he was featured on an episode of Inside Evil, a show on HLN hosted by Chris Cuomo. He ended up on the show after contacting a producer at CNN, seeking to promote a story he had written for The Marshall Project in collaboration with Keller. Instead of treating Lennon like a journalist, the producer referred him to Chris Cuomo’s show, which was at the time called Inside. Lennon learned of the name change the morning of his interview with Cuomo; he proceeded because at the time Cuomo’s brother was the governor, “the one elected official with the power to commute your sentence and set you free.”

The episode, “Killer Writing,” juxtaposed their interview with “scenes of shadowy, faceless reenactments of the shooting and photos of my mug shot, with close-ups of my eyes, bloodshot from all the drugs.” Lennon writes, “I can no longer separate these images from my actual memories of what happened that night.” For some of the New York State officials responsible for reviewing Lennon’s clemency petition, the images from Inside Evil seem to override anything else they have learned about how he has changed during his time in prison. Brooklyn District Attorney Eric Gonzalez was reportedly “really spooked” by the episode, and the governor’s clemency bureau “fixated” on “Killer Writing” in a meeting with Lennon’s legal team. “I couldn’t believe that people at the highest levels of government were so influenced by this lurid rendering of my story,” Lennon writes. But government officials are just as susceptible to true crime’s simplistic storytelling.