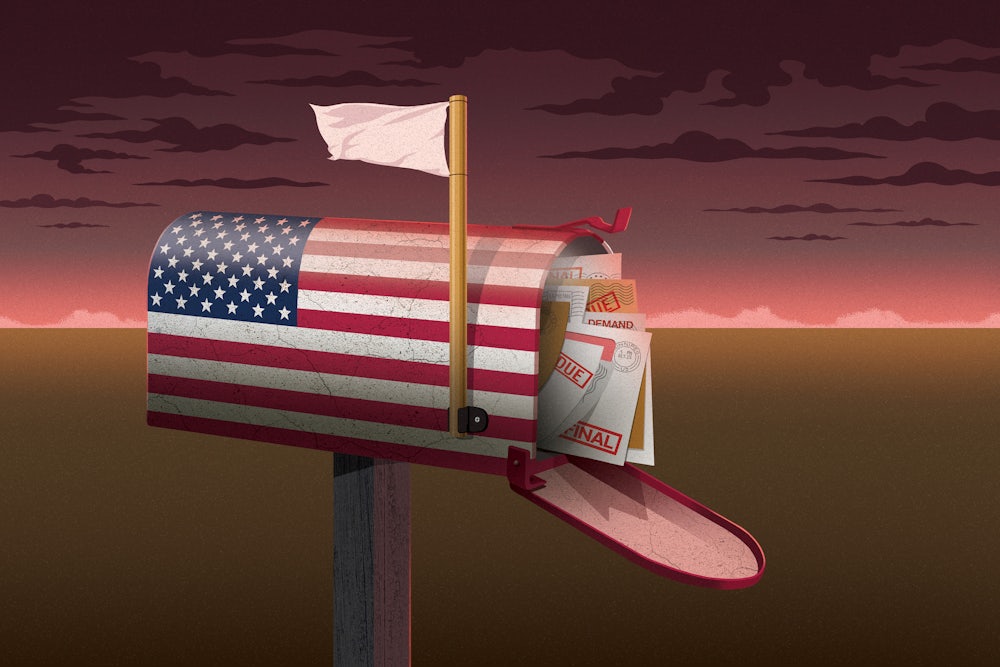

There is no collapse. No Lehman Brothers moment. Instead it’s a slow burn, a financial treadmill that many are never able to get off. Across the country, households are juggling a web of obligations: student loans, credit cards, car payments, medical bills, rent, utilities, and even financing for necessities like groceries.

Americans are falling behind on their bills at rates not seen in years. Car payment delinquencies are at their highest point in decades, credit card defaults have climbed to levels last reached in 2010, and student loan delinquencies have surged since repayment resumed, with nearly one in three borrowers at risk of default. Total household debt has hit an all-time high of $18.4 trillion in the second quarter of 2025, and the average household now owes more than $100,000—a 13 percent jump between 2020 and 2024.

Unlike the 2008 crash, this crisis isn’t unfolding in a way that makes the nightly news or regularly features on the front page of The New York Times. Indeed, it has rarely gotten any sustained media attention at all. There’s no single domino to point to, no sudden breakdown that can be explained in a neat narrative. Corporations aren’t going under—they’re doing quite fine, in fact. This is a crisis, rather, that is made up of thousands of cuts, millions of small financial emergencies that have accumulated to become something structural: a system where debt is the default condition of American life.

The transformation didn’t happen overnight. In the last half-century, real wages have stagnated while the costs of housing, health care, and higher education have soared. Where steady, unionized jobs once offered a path to stability, today’s economy leans on low wages, gig work, and eroded benefits. Borrowing has become the safety net—one that comes with interest rates and late fees.

Credit card debt quietly crossed the $1 trillion mark in the second quarter of 2023, a milestone that was covered by dozens of outlets before all but disappearing from public notice. The average balance per cardholder with debt stood at $7,321 at the start of 2025, and the United States leads other developed nations in credit card debt burdens. In recent years, the Debt Collective, which describes itself as a union for debtors, has highlighted growing debt in new forms: abortion-related debt, driven by higher procedure costs and the added travel expenses faced by those who, post-Roe, no longer live near a provider; rising utility debt as electricity prices spike; and back-rent debt from pandemic-era eviction moratoriums, which left tenants owing thousands to corporate landlords.

Braxton Brewington, a spokesperson and organizer with the group, recalled one renter facing $90,000 in eviction debt. The actions of corporate landlords follow a clear pattern, Brewington said. “They evict people incredibly fast. They’re doing it with surgical precision. It’s highly racialized across the country.” And of course abortion debt wasn’t even a term people were using before Roe was overturned.

Meanwhile, the rise of “buy now, pay later,” or BNPL, loans—which allow online consumers to purchase items and pay for them in installments—is a new and growing problem. Once marketed as a way to make large purchases like concert tickets or jewelry more manageable, such loans are increasingly being used for everyday expenses. And although they account for a relatively small share of online shopping, their expansion has been striking, jumping from 2 percent of e-commerce transactions in 2020 to 6 percent in 2024. A recent survey from LendingTree found that nearly a quarter of BNPL users are now using loans for groceries. “We’re constantly hearing about it from people,” Brewington said. “I’m not sure if people always conceptualize themselves as taking on debt.” In March, DoorDash partnered with the financial tech service company Klarna, giving customers the option to defer payments on takeout orders. The move was greeted with ridicule online—“We are securitizing burritos and selling them to willing buyers at fair market value,” one poster joked—but a tidal wave of derision did nothing to halt BNPL.

The spread of BNPL into routine spending, more than just shifting consumer preferences, suggests mounting financial strain. And while the popular option—the interest-free “pay-in-four” plan—is often marketed as a no-stress solution, it may soon carry more weight. In June, FICO announced it would begin including BNPL loans in credit reports, a move that could turn even a short-term splurge into a long-term mark on a borrower’s financial record.

Installment credit has a long history in the United States, according to economic historian Louis Hyman. It took off in the 1920s, when it was a regular feature of department store shopping, and stayed popular through the midcentury until credit cards emerged. In the 1980s and 1990s, it was marketed to lower-income households for essentials like furniture and appliances. E-commerce has fueled its latest boom. “For people like me, who thought of it as kind of an old-fashioned way of offering credit to people, it’s kind of surprising that it’s caught on like wildfire,” Hyman said, “especially since so much of the older installment credit system was about repossession.”

In his book Debtor Nation: The History of America in Red Ink, Hyman explains that, over the course of the twentieth century, debt shifted from a marginal practice to a central feature of American life. In the post–World War II economy, Hyman says, “People borrowed for their cars, and houses, and socks, and furniture, but their wages grew immensely.”

During that period, bankers slowly realized the lucrative potential of consumer lending. Rising wages gave households the means to borrow and repay, making personal loans a reliable and profitable business. But beginning in the 1970s, financialization accelerated, real wages stagnated, and credit became a substitute for rising incomes. “In the post-war period, the 1 percent paid the 99 percent wages. After 1970, the 1 percent just lent the 99 percent money,” Hyman says.

That shift didn’t just change how people borrowed. It reshaped the safety net. As public benefits remained weak or eroded, policymakers leaned on private credit to fill the gap. Today, nearly 40 percent of Americans can’t cover a $400 emergency expense. The strain is worse for women: 49 percent report having no emergency fund, compared to 36 percent of men.

“We have a really flimsy welfare state to begin with,” said Sarah Quinn, a sociologist at the University of Washington. “That’s absolutely under attack in the current political environment.” Quinn points to what scholars call the credit-welfare state trade-off, where weak public benefits are offset by policies that expand access to private credit. The result is that households end up borrowing to cover costs like housing, education, and health care.

Few examples capture this trade-off more vividly than medical debt, a roughly quarter-trillion-dollar burden that, by some estimates, contributes to over 60 percent of bankruptcies. Nearly one in five Americans now has medical debt listed on their credit reports, while more than half of all items in collections on credit reports are medical bills. This burden is not evenly distributed either: 28 percent of Black Americans and 22 percent of Hispanic Americans carry past-due medical debt, compared to 17 percent of white Americans, according to U.S. Census Bureau data. In the United States, where health care is neither universal nor affordable, the credit system turns illness into a lasting penalty that lands hardest on the poorest and those who are not white.

Consumer debt is a crisis without a cliff. It’s also a story that the news media has struggled to cover adequately. In 2008, massive financial institutions were collapsing—now credit card companies and other lenders are thriving. The victims are ordinary people dealing with a suffocating problem that doesn’t produce the kind of inflection point that drives much of mainstream media coverage.

That absence of drama often makes the consumer debt crisis easier to ignore. Even major actions that draw attention to the problem—the Debt Collective recently launched a “debt strike” focused on back rent as well as a national dispute tool that helps tenants challenge their corporate landlords—are often given little coverage and are often only covered by smaller outlets catering almost exclusively to progressives.

But even without a mass debtors’ movement, affordability has started to emerge as a potent political rallying cry. In New York City, Zohran Mamdani won a decisive primary victory in the mayoral race with a campaign promise of “A New York You Can Afford,” a slogan shaped by conversations at doors in neighborhoods (including some that backed Donald Trump) where residents kept naming the same problem: Everything costs too much.

Nationally, Bernie Sanders has drawn impressive nonelection-year crowds with his “Fighting Oligarchy Tour,” hammering home a statistic that ought to haunt policymakers: 60 percent of American households cannot afford a “minimal quality of life.” These moments suggest that the pressures on household budgets are no longer background noise but active political forces. It seems plausible that at least one Democratic candidate, and maybe several, will make the debt crisis a foundational part of their policy platform during the 2028 presidential primary.

In the meantime, the next wave of financial strain is already taking shape. New tariffs threaten to raise the price of everyday goods. States are moving to cut Medicaid. The White House fired the chief of the Bureau of Labor Statistics after an unfavorable jobs report, stoking fears of political meddling in economic data.

And in Washington, even long-planned consumer protections are being rolled back. In July, a Trump-appointed judge vacated a Biden-era rule that would have removed medical debt from credit reports. The rule would have eliminated reporting on an estimated $49 billion for some 15 million Americans. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, which championed the policy under director Rohit Chopra, reversed course earlier this year and joined credit-reporting industry groups in urging the court to scrap it. The Debt Collective, which worked closely with the CFPB during the Biden years, still refers people to the agency, but with far less confidence it will deliver solutions.

“We end up in a situation where every problem becomes a financial problem—a problem to be fixed with financial technologies and credit markets—because it’s hard for Americans to imagine the proper levels of taxation for redistribution,” Quinn said. “And this was even before the tax cuts.”

For now, Americans are struggling to stay afloat. But the current is moving in one direction, and it’s not toward shore.