In late 2024, an operative for the right-wing gotcha group Project Veritas clandestinely filmed his Tinder date with a 29-year-old EPA employee. The employee, who talked freely about his work distributing grant funds allocated by the Inflation Reduction Act, at one point compared that process to “throwing gold bars off the edge” of the Titanic, i.e., dispatching grants quickly before the proverbial iceberg, Donald Trump, took office and clawed back the funding.

A few months later, Lee Zeldin, the new head of the Environmental Protection Agency, announced a remarkable discovery: “My awesome team at EPA has found the gold bars. Shockingly, roughly $20 billion of your tax dollars were parked at an outside financial institution by the Biden EPA.”

There were no actual gold bars, of course. And Zeldin probably didn’t need a team to find them. Those $20 billion were part of the $27 billion Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, or GGRF, a program that was meant to help low-income communities finance and develop renewable energy projects with IRA-funded grants to nonprofits. The EPA had used Citibank to transfer the funds; nearly $7 billion went to a single “far-left activist group,” in Zeldin’s description, called Climate United. (Among the supposedly radical plots the nonprofit planned to finance with that money was preconstruction on a University of Arkansas solar project, projected to save the state $120 million in energy costs.)

Alleging fraud, the EPA and the FBI demanded that Citibank freeze those funds and referred the case to the Justice Department. While such requests are normally granted only with a court order, Citibank complied, just days after Zeldin’s initial announcement. FBI agents started showing up at the homes of Climate United employees, who faced tongue-lashings by right-wing news outlets and subpoenas from Republican-controlled congressional committees that had initiated their own investigations. The DOJ’s investigation found no evidence of criminal wrongdoing, however, and GGRF grantees remain locked in a legal battle with the EPA that may eventually end up in front of the Supreme Court. This spring, the EPA informed Climate United that it had terminated its grant not because of fraud but rather because of a change in administrative priorities.

“We briefly joked about renaming our organization Gold Bars LLC,” said Phil Aroneanu, Climate United’s chief strategy and partnerships officer.

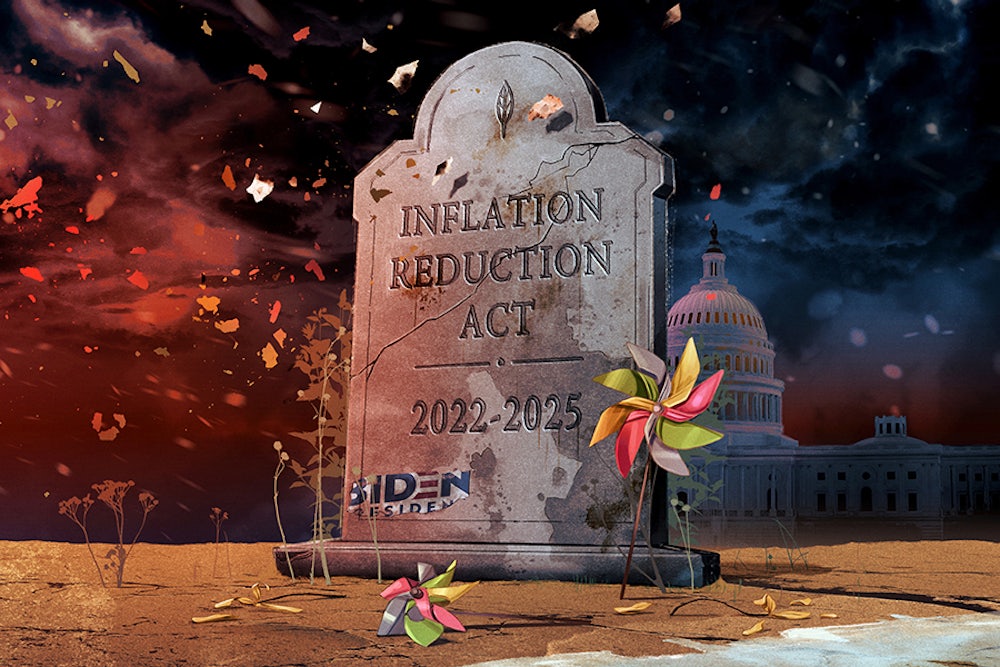

The ordeal was a sign of things to come. Since Trump took power, his administration has waged a multifront war on its ever-growing list of political enemies. In July, Republicans’ One Big Beautiful Bill Act, or OBBB, repealed much of the Inflation Reduction Act’s nearly $400 billion worth of climate- and energy-related grants, tax incentives, and loan guarantees. While the OBBB stopped short of a full repeal of the IRA, it took a sledgehammer to the parts projected to drive down the most emissions. Subsidies for residential customers to lease solar and wind ended immediately. Consumer-side incentives for purchasing electric vehicles and residential energy efficiency upgrades expired in October. Generous tax credits for wind, solar, and hydrogen projects, as well as wind manufacturing, will be phased out years ahead of schedule.

The Trump administration’s war on the Inflation Reduction Act and all things climate embodies the horrors of Republican rule: a paranoid, lawless crusade waged by extremely online ideologues who are using their control over every branch of government to stoke culture wars, settle scores, and please their deep-pocketed donors. “I don’t feel scared about being targeted,” Aroneanu told me, “but I’m scared for our country.... I know what they can do if they want to target their political opponents. They can steal our money from our bank accounts. They can try to get us fired. They can drag us in front of congressional committees. They can open up sham DOJ investigations. They can drag our names through the PR machine and Fox News.” The Inflation Reduction Act was a perfect scapegoat because of how it encapsulated Democratic governance: a Frankenstein-ish vehicle for progressive economic ideas, emissions reduction, justice, geopolitics, and the idiosyncratic, donor-informed beliefs of lawmakers who enjoyed outsize power thanks to the party’s razor-thin congressional majority. Initially envisioned as a decadal project of national renewal that could build enthusiasm for the party and its ideas across partisan lines, the IRA—a much narrower law than its architects had hoped—was instead gutted, without much fanfare, less than three years after it passed.

Many people I spoke to for this piece, who played significant roles in the bill’s creation, thought it might prove more durable, not least because many of its provisions stood to benefit red states. While the IRA wasn’t designed to funnel more money into Republican districts, nearly three-quarters of investments spurred by the bill flowed to states that swung for Trump in 2024. As of May, $642 billion of the private-sector clean energy investments announced since the IRA passed were in Republican-controlled congressional districts, compared to $187 billion of announced investments in Democrat-controlled districts. Reasonably enough, one White House deputy reported having been “very hopeful that because these clean energy investments were going into red places, that would create some bipartisan buy-in.”

Few Republicans resisted repealing it, however. Just 18 Republican House members sent a gently worded letter to House Speaker Mike Johnson asking him to preserve some portions of the bill even as they supported axing others. Every signatory who was in Congress when the OBBB came up for a vote backed it.

On one hand, the reasons this happened are simple: The GOP is dead set against anything it considers to be climate policy. But as Democrats grope around for a viable strategy to win back power, it’s worth taking a closer look at why one of the Biden era’s signature legislative achievements could be cut down so quickly and unceremoniously.

Only 35 percent of voters surveyed by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication last spring reported having heard “a lot” or “some” about the Inflation Reduction Act. Even more remarkably, less than half (47 percent) of self-identified pro-climate voters either hadn’t heard of the IRA or had only heard “a little” about it. For all the many successes of the IRA—at least $100 billion in grants, 330,000 jobs, and $450 billion in private investment in nearly every state—the law and its supporters failed to make the case for its continued existence. How did the IRA happen? What did its architects hope it would accomplish, and what could a more successful governance agenda look like for a country plagued by climate change, inequality, and authoritarianism? Where, in other words, did we go so wrong, and how can we find our way back?

To properly answer these questions, you need to go all the way back to the last time Democrats attempted to pass major climate policy. Structuring the Inflation Reduction Act around “climate, jobs and justice” was, in part, a corrective to the party’s failed push in 2009 and 2010 for cap-and-trade—a method of carbon pricing whereby polluters earn, buy, and trade “credits” to comply with a declining cap on their emissions. The problem wasn’t just that the American Clean Energy and Security Act—better known as Waxman-Markey—had failed, or even that like-minded state- and national-level efforts imploded in subsequent years. Right-wing backlash to that bill dramatically shifted the politics of climate change in the United States, transforming it into a solidly partisan issue. Republicans’ 2008 nominee for president, John McCain, had a mixed record on environmental issues. But he campaigned on cap-and-trade and talked about the need to address “all the endless troubles that global warming will bring.”

After McCain lost, Democrats sought to build a bipartisan coalition for cap-and-trade. To do that, they leaned on big companies like Duke Energy and BP to help craft a plan that might court Republican votes and quiet opposition from other polluters. The resulting bill passed the House in summer 2009. Americans for Prosperity—a political action committee backed by Koch Industries’ fossil empire—subsequently mounted aggressive protests and successful primary challenges against Republicans who dared to even talk about climate change. As Kochland author Christopher Leonard wrote years later, these efforts “sent a message to other Republicans: Koch’s orthodoxy on climate rules could not be violated.” Polluters who’d backed the bill withdrew their support for Waxman-Markey, and it died before coming to a vote in the Senate in 2010. John Podesta—the Clinton White House alum who co-chaired Barack Obama’s transition team—supported the bill while serving as president of the Center for American Progress. Once the cap-and-trade push imploded, he told me, Democrats “came back in the minority in 2011 and said, ‘It’s just too tough.’”

As climate sat on the back burner, new ideas took root within the party. America’s slow and deeply unequal recovery from the Great Recession convinced most Democratic wonks that the key risk in responding to economic shocks and crises wasn’t spending too much on a stimulus, but too little. A new generation of economic policy experts, who’d internalized those lessons in grad school and early-career posts during the financial crisis, took on more prominent positions in Washington. Rather than treating big fiscal spending primarily as a short-term way to stimulate the economy in a downturn, they saw policies like a federal job guarantee, universal childcare, and Medicare for All as necessities for tackling persistent racial, wealth, and gender inequality. Bernie Sanders’s bid for the Democratic presidential nomination in 2016 provided a national platform for those ideas that continued to grow after his loss.

It’s easy to forget just how quickly climate change emerged as a rallying cry for Democrats in Trump’s first term. Adrian Deveny was Oregon Senator Jeff Merkley’s legislative director in 2017 when he heard about an opening for a senior position to cover climate policy in the office of the venerable Senate minority leader from New York, Chuck Schumer. For Deveny, the idea of working for the majority leader was compelling, particularly a few years out from a prospective Democratic trifecta in 2021. “My whole purpose in going to the Hill was to work on climate policy,” Deveny told me; this would be a chance to do that at an excitingly large scale. Deveny applied and interviewed for the job. Then nothing. More than a year went by.

Finally, in November 2018, Democrats took back the House. A few days later, some 200 young people with the Sunrise Movement streamed into Nancy Pelosi’s office, demanding that the next majority leader make a plan to deliver “good jobs and a livable future.” Joining them was Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the 29-year-old who’d rocketed to political stardom after pulling off an upset victory in New York. Like other candidates who won that year, she’d run on a platform of populist proposals that had been circulating within left-leaning think tanks and advocacy organizations. “We need a Green New Deal and we need to get to 100 percent renewables because our lives depend on it,” Ocasio-Cortez told reporters. “Climate change and addressing renewable energy always gets to the bottom of the barrel,” she continued. “[We need to] create a momentum and an energy to make sure that it becomes a priority for leadership.”

A little over a month later, Deveny got a callback from Schumer’s team; he’d gotten the job. “I think he recognized that the substance [of climate policy] was important, that he needed to be better educated on it, and he wanted to show leadership on it,” Deveny said. At Merkley’s office, he’d become “obsessed” with the idea of trying to write sizable climate policy through reconciliation—a process that allows for passing tax-and-spend bills with a simple majority, overriding the filibuster. Schumer was on board. They spent the next two years pulling together proposals from congressional offices and committees that could make it into an eventual package, and devising a strategy to ensure it could pass.

As climate protests continued to capture headlines at home and abroad, candidates chasing the Democratic Party’s 2020 presidential nomination competed over who could pledge more trillions to slash emissions. The most ambitious of those proposals was Sanders’s $16 trillion Green New Deal, which posited climate action as an engine for combating inequality.

The pandemic strengthened progressives’ case for bolstering the welfare state. Although Trump 1.0 catastrophically mishandled public health at the height of Covid-19 infection rates in 2020 and 2021, his administration acceded to Democratic proposals for expanded SNAP and unemployment benefits and a national eviction moratorium that kept untold numbers of Americans alive and above water. Funded by the CARES Act in late March 2020, Operation Warp Speed provided high-level R&D support to mRNA vaccine researchers, and guaranteed pharmaceutical companies that the government would buy virtually unlimited quantities of successful jabs. Vaccine development ordinarily takes years, even decades. Shots were in Americans’ arms by the end of 2020. Trade disruptions helped drive up the cost of everything from PPE to used cars, exposing how fragile and lopsided globalized supply chains had become.

The Democratic Party’s policy agenda coming into 2021 reflected a decade’s worth of heterodox thinking about the relationship between the state and the economy, as well as a resurgent progressive energy around climate expressed most fully in demands for a Green New Deal. The pandemic seemed to vindicate both. All this opened up the inner sanctum of the party’s policymaking apparatus to ideas that had lingered on its fringes. A series of “unity task forces” convened Sanders and Biden surrogates to draft the latter’s general election platform. Even the older guard of advisers surrounding Biden—Ron Klain, Steve Ricchetti, and Bruce Reed—got on board with the idea that a successful economic agenda would require massive spending to prevent an economic crisis; address structural vulnerabilities exposed by the pandemic; and reduce greenhouse gas emissions through public investment that would fuel job creation in important twenty-first-century growth industries.

Decarbonization, in other words, became an all-purpose vehicle for delivering on a wide range of party priorities, including geopolitics. Nancy Pelosi was eager to pass Build Back Better through the House before arriving at U.N. climate talks in Glasgow in November 2021, so that it might serve as a “model for the world.” The White House similarly saw U.S. leadership on climate as a chance to mark a break with Trump on the world stage, and galvanize the private sector to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement. Secretary of State Antony Blinken argued at George Washington University in 2022 that “there’s no better way to enhance our global standing and influence than to deliver on our domestic renewal. These investments will not only make America stronger; they’ll make us a stronger partner and ally as well,” adding that the United States wanted to “lead a race to the top on tech, on climate, infrastructure, global health, and inclusive economic growth.”

China loomed large. The country’s rapidly growing market share in everything from critical minerals processing to solar panels and EVs inspired fears of a second “China Shock” that threatened to undermine U.S. workers and global leadership. “If we don’t make clean energy here in America, the America that we have had, all the good and all the bad, will not be the same economic superpower or global superpower in 20, 30, or 50 years,” Heather Boushey, a member of Biden’s Council of Economic Advisers, told me. She was later appointed as chief economist for the White House’s Invest in America Cabinet. “If you concede the race in what is probably the most important set of technologies for the future, your economy is not going to have a future.”

The framework that eventually became the Inflation Reduction Act—the American Jobs Plan—accordingly rested on a production-oriented industrial strategy that combined major infrastructure investments with an attempt to make the United States globally competitive in clean energy, batteries, semiconductors, and biotechnology. The American Jobs Plan would “create millions of good jobs, rebuild our country’s infrastructure, and position the United States to out-compete China,” per a White House overview. Rapidly deploying clean energy at home would help the United States reach the targets it had set for itself under the Paris Climate Agreement, to reduce economy-wide greenhouse gas emissions by at least 50 percent below 2005 levels by 2030. In addition to improving bridges, highways, and water pipes, and revitalizing manufacturing in strategic, export-oriented sectors, the plan also sought to tackle critical needs in housing and care that threatened to undermine growth and productivity. Those priorities were carried over to the Build Back Better framework the White House announced in October 2021. The biggest line items were for clean energy and climate investments ($555 billion) and childcare and preschool ($400 billion), with an additional $150 billion each for home care and housing.

The labyrinthine process by which the White House’s $3.5 trillion Build Back Better framework became the $891 billion Inflation Reduction Act successively eliminated programs from earlier proposals that mig ht have been able to provide near-term, tangible relief on inflation and affordability. This shrinkage happened, in part, because various pieces of the Biden administration’s broader economic vision were spun off into separate pieces of legislation: the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan; the $280 billion CHIPS and Science Act, focused on semiconductors and advanced manufacturing; and the $1.2 trillion Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. That made eventually passing Build Back Better’s more expansive version in 2022—including robust investments for housing and the care sector—a more difficult sell in Congress. Nearly $800 billion for childcare, universal pre-K, and home health care was cut out entirely. In the end, what became the Inflation Reduction Act was the version of Build Back Better that was acceptable to Kyrsten Sinema and, especially, Joe Manchin. Thanks to his decisive vote in a 50–50 Senate, the West Virginia senator and coal magnate spent months presenting demands to Senate leadership and the White House on the overall size of the package, what he wanted to include, and what should go: welfare state programs, requirements that federally backed EV production hire union labor, and any language that might limit fossil fuels.

Sunrise Movement co-founder Evan Weber—then its political director—had by that point spent years on regular calls with the congressional offices and the White House, which solicited input on everything from personnel decisions to policy design. Sunrise activists swarmed Manchin’s houseboat, Almost Heaven, on Washington’s Wharf and confronted him in a parking garage, demanding a deal he didn’t seem eager to make. The excitement of nonstop meetings and press coverage for Sunrise since the sit-in at Pelosi’s office in 2018 was, for Weber, congealing into bitter disappointment, as negotiations with Manchin ground to a halt in December 2021. “How can you have the highest youth voter turnout in history, do all the right things in a campaign,” he told me, “and still the whims of one senator elected by a couple hundred thousand voters can determine the fate of a country of hundreds of millions of people?”

Early the next spring, senior administration officials coaxed Manchin back to the table with a charm offensive involving late-night moonshine and singing around a bonfire at his condo in the Canaan Valley. Infuriatingly for the staffers who’d spent months accommodating his demands to strip out care and climate provisions, Manchin walked away for what seemed to be the last time in June. Then, at the tail end of July, Schumer’s office reached a surprise closed-door agreement with him on what was soon called the Inflation Reduction Act.

What survived that eleventh-hour rebrand was a program to deploy renewables and revitalize U.S. manufacturing by incentivizing private investment in lower-carbon technologies, and to lower prescription drug prices. Top Democrats hoped the bill would create jobs at home and make a suite of green sectors competitive worldwide. To generate domestic demand and facilitate deployment, the IRA used a combination of buy-side tax credits (e.g., EV rebates) and stringent domestic content requirements to penalize cheaper imports of both finished products and inputs like lithium and anodes. All that would have the added benefit of reducing emissions, chiefly in the power sector. Several grant programs, including GGRF, were designed to reduce pollution and improve public health in marginalized and underserved populations, and communities overburdened with climate and environmental pollution. These would help further the White House’s “Justice40” initiative, pledging that 40 percent of the “overall benefits” of federal spending on climate, clean energy, and other investments flowed to those same places.

According to the text of the IRA, spending would roll out over 10 years. But the bill itself contained relatively few immediate benefits that might have allowed Democrats to make the case for their reelection in 2024. Building and retrofitting factories—particularly for fledgling industries targeted by IRA incentives—take several years. To make matters worse, inflation, rising interest rates, and supply-chain snarls created a more challenging business climate in the sectors the IRA targeted for growth. By August 2024, a report from Financial Times found that 40 percent of major manufacturing investments announced in the year after the IRA passed had been delayed or paused indefinitely. “Companies said deteriorating market conditions, slowing demand and lack of policy certainty in a high-stakes election year have caused them to change their plans,” FT reported.

The Biden administration’s hope that the industries receiving subsidies might rebuff Republican attacks on Democrats and the legislation itself never materialized. Republican politicians whose districts became core beneficiaries of IRA-backed investments had little incentive to fight for them: Although repealing the IRA could end up reducing private-sector investment in their districts, safeguarding the Biden administration’s trademark legislative achievement from Trump’s—voting no on the One Big Beautiful Bill—might well cost them their seats in the next election.

What went wrong? Across more than a dozen interviews with people involved in designing, lobbying for, and implementing the IRA, nearly everyone pointed to basic mismatches between what the bill was designed to deliver, whom it could deliver for, and when. Core to its political pitch was a theory that “by linking climate investments with economic benefits, we would spur a broad, popular clamor to defend those investments and expand on them in future legislation,” said Ben Beachy, who joined the White House Climate Office in 2023. “We would create a virtuous cycle, the theory went, in which climate investments would yield economic benefits, garnering votes for more climate investments. And I think it’s safe to say that that has not happened.”

The fundamentals of the U.S. economy shifted dramatically between the time when Build Back Better was being drafted and when the Inflation Reduction Act took effect. Inflation started to rise steadily nearly as soon as Biden took office, and by the time the final text was agreed to in late July, it had already soared to more than 9 percent. A last-minute name change tried to incorporate that reality, as did White House press releases emphasizing how its economic agenda was “lowering costs in every corner of the country.” At the end of the day, though, incentives to make, build, and buy low-carbon technologies weren’t suited to address mounting concerns about the rising cost of groceries, housing, and even gas and utility bills. “We were used to decades of low interest rates and slack labor markets,” said Alex Jacquez, who worked for Bernie Sanders in the Senate and in his 2020 campaign before joining Biden’s National Economic Council in March 2021. But “very quickly, it turned out that our problem was not jobs. It was going to be inflation, and we had no response to it.”

Policymakers were aware that the vast majority of projects made possible by the IRA wouldn’t break ground and start hiring permanent workers until well after the next presidential election. Yet they didn’t plan how to communicate the long-term nature of the IRA’s climate and investment program either to the broader public or to people who lived where those projects were slated to happen, including the deindustrialized areas being hit hardest by inflation. The high-tech nature of factories producing battery cells, for instance—involving specialized robotics—meant that much of the manufacturing spurred by the IRA wouldn’t resemble traditional assembly-line jobs. That announced investments were concentrated in the South also required unions to invest considerable resources into organizing new plants. Even if there had been slightly more time for those investments to pay off (i.e., for factories to open and start hiring), and if implementation had proceeded more quickly, the political dividends of manufacturing investments appeared fated for modesty: Just 9 percent of the country actually works in manufacturing.

The sheer dollars pledged in earlier iterations of the bill made it easier to imagine those budget frameworks accommodating everyone from China hawks to youth climate activists, energy executives, and unionized home health aides. As Build Back Better was whittled down into the IRA, the coalition that stood to benefit from it before the next election shrank. Its durability, therefore, depended more on the automakers, geothermal energy entrepreneurs, residential solar installers, and hydrogen producers who could collect on IRA funds to help finance new projects. The law’s main near-term beneficiaries, in other words, were hardly a coherent or organized bloc of “green capitalists” brought into Democrats’ fight to “win the future.” They were companies with wildly divergent business models and political preferences.

Those with the most to gain right off the bat were “pure-play” companies without much political clout and with their own competing priorities. Solar manufacturers, for instance, cheered on tariffs against imports from China, which produces some 95 percent of the polysilicon key to panel production. Solar installers rebelled against tariffs for driving up costs. Still more IRA subsidies flowed to larger, diversified utilities and multinationals like Exelon, Exxon, and GM. Those bigger names, especially, were happy to accept federal subsidies for lower-carbon technologies while continuing to battle regulations viewed as a core threat to their high-carbon bread and butter, and donating generously to Republicans vowing to dismantle the IRA.

The Edison Electric Institute—a trade association for investor-owned utilities—offers a perfect illustration of industry’s Pollyannaish approach. It praised the IRA after its passage for placing the United States “at the forefront of global efforts to drive down carbon emissions,” and providing “much-needed certainty to America’s electric companies over the next decade, as they work to deploy clean energy and carbon-free technologies.” Less than two years later, EEI sued the EPA over rules to limit greenhouse gas emissions from fossil fuel–fired power plants. The group gave fewer federal campaign contributions to Democratic Party candidates in 2024 than it had in the previous two election cycles; EEI gave a larger proportion of those funds to Republican candidates (nearly 59 percent) than at any point since 2016. After the GOP passed its One Big Beautiful Bill Act, EEI applauded the law.

While high-profile green capitalists had been instrumental in passing the bill—most infamously when billionaire philanthropist and energy investor Bill Gates met with Manchin—the biggest companies had little incentive to champion the IRA once funds started flowing. The White House’s communications strategy rested on convincing the companies receiving tax credits to reference them in press releases and announcements about new investments. “It was a slog,” said one Biden administration staffer. The theory was that “if we give companies a bunch of money to do good stuff, they’ll help us tell the story,” the staffer explained. “But that was never the central story that most companies were willing to tell.”

Firms that sought out funding through the IRA also leaned heavily on state and local governments that offered their own incentives for companies to locate projects there. Democrats and the Inflation Reduction Act, accordingly, rarely got top billing at ribbon-cuttings. Democrats were instead relegated to being among many supporters who’d help to make new projects possible. Neither were there the mechanisms or political will to use the sizable federal subsidies companies received as leverage to neutralize their opposition on other fronts: Corporations could continue to receive billions from the federal government as they did battle against its rulemaking. “Once you pass the bill, they’re just gonna keep opposing the sticks,” i.e., the regulations, the same White House staffer said. “Why wouldn’t they? There’s nothing to lose because we don’t have any leverage.”

IRA subsidies did not align a loosely defined bloc of corporations behind the administration’s domestic and international goals to slash emissions, outcompete China, reduce inequality, and encourage voters in deindustrialized, increasingly Republican-leaning parts of the country to credit Democrats for a manufacturing revival that was years away. By conventional metrics, the Biden administration racked up remarkable economic wins: the strongest post-pandemic growth of any wealthy country, strong wage growth, historically low unemployment, and, eventually, tamed inflation. Despite all this, many in the United States still found themselves materially worse-off than when Biden took office. The largest decrease in child poverty ever recorded in the United States, in 2021, was followed by the largest-ever increase in child poverty the next year. Thanks in part to the withdrawal of pandemic-era programs, real per-capita income was 6 percent lower in 2022 than in 2021.

Democrats’ attempts to champion their investment- and infrastructure-focused legislative accomplishments in the 2024 election were out of step with voters’ concerns. “They didn’t give a fuck about bridges,” Jacquez told me. “They just wanted lower prices.”

If the coalitional math of the IRA was wrong, what calculus would be better? In the wake of Trump’s second election, some Democratic pundits and politicians have zeroed in on the Biden White House’s early focus on “climate, jobs, and justice” as emblematic of a party that’s been overly accommodating to special interests like the Sunrise Movement and alienating to the moderate swing voters needed to win back majorities. A winning coalition, centrists argue, requires jettisoning the sorts of progressive groups that strong-armed Democrats into talking about the climate crisis. Making that case earlier this year, Matt Yglesias wrote that the “climate movement” constantly risks pushing Democrats “into the danger zone” electorally by pushing unpopular positions like phasing out fossil fuels and gas-powered cars. While Americans care about climate and the environment in some abstract sense, he added, “they care about jobs and economic growth more than they care about getting to net-zero as quickly as possible.”

Yglesias is right in some important respects: While a majority of people in the United States reliably tell pollsters they’re concerned about climate change and want the government to do more, very few rank it among their top priorities at the ballot box. But there are plenty of reasons to doubt stories that blame the party’s flagging electoral performance on progressive climate advocates. Biden and Kamala Harris barely mentioned climate change on the campaign trail in 2024. Their White House oversaw record-setting levels of oil and gas production, and practically pleaded with companies to drill more. Bidenomics, moreover—anchored by the IRA, the CHIPS and Science Act, and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law—was always much more squarely focused on jobs and economic growth than on reducing emissions. The White House’s “modern industrial strategy,” national security adviser Jake Sullivan summarized at the Brookings Institution in October 2024, was “premised on investing at home in ourselves and our national strength, and on shifting the energies of U.S. foreign policy to help our partners around the world do the same.”

People care much less about what generates their electricity than how much that electricity costs; decarbonization is not a winning message. Neither, however, is an industrial strategy laser-focused on jobs and growth. Bidenomics’ reasonably successful quest to encourage companies to build lots of stuff didn’t win Democrats lots of votes.

In a bid to hammer Trump on skyrocketing utility bills—U.S. households are paying 10 percent more per kilowatt hour for electricity than they did in January—some Democrats are now looking to rebrand as the “party of cheap energy.” House Democrats accordingly introduced a slate of proposals this fall to encourage new power line construction, strengthen utility regulation, and restore tax credits for wind and solar energy slashed by the OBBB. “It’s a happy coincidence that cheap is synonymous with clean,” Illinois Representative Sean Casten, a co-sponsor, told Heatmap News. “But the goal is cheap.”

Will voters care more about transmission lines than they did about battery and semiconductor manufacturing? And are Democrats up to the task of communicating to the masses about how wonky fights over regional grid planning and Federal Energy Regulatory Commission rulemaking translate to monthly bills that are lower than they might have been otherwise?

It seems unlikely. Managing energy prices is notoriously difficult, often requiring the kinds of stringent price controls that—even in blue states—would entail massive political fights to implement. And however disciplined politicians are about sticking to poll-tested messaging about affordability, Republicans can be expected to hammer any policies that boost renewables as a “Green New Scam.” Even if Democrats part ways with emissions reduction goals, energy policies that maximize purely for the cheapest energy—i.e., that don’t punish renewables—will run headfirst into the GOP’s opposition to wind and solar, as well as a right-wing news ecosystem that paints them as both prohibitively expensive and ontologically evil. There may be no amount of green investment in red states that would convince sizable numbers of Republican politicians and voters to support Democrats and decarbonization. The Texas State Capitol, for instance—nestled with the country’s largest statewide generator of wind power, and second-largest in utility-scale solar—remains a laboratory for far-right, fossil fuel–funded assaults on everything from environmental regulations to sustainable investment and democracy itself.

Climate politics in the Biden era sought to correct for the failures of Waxman-Markey by focusing on emissions reduction as a driver of job creation and economic growth, not complex mechanisms for pricing carbon. Ironically, the IRA’s survival was premised on the same logic Democrats hoped would pass cap-and-trade: that a loose alignment of corporations would support climate policies in exchange for subsidies, then convince Republicans to get on their side. That didn’t work, and very few people in the United States could readily explain how either the IRA or carbon pricing would improve their lives. Most Americans don’t know what those things are.

Nearly everyone I spoke to agreed that climate advocates, and Democrats more generally, should focus more on the affordability concerns that may have cost their party the 2024 election. “Things that can provide direct benefits to households and be implemented quickly should be at the top of the list,” John Podesta told me when I asked him what climate policy in a post-IRA world should look like. “The most important thing is to make sure that households are feeling this not just as a theoretical issue in five years.”

As the effects of the climate crisis become more widely felt in worsening storms, fires, and floods, the question is whether energy policy—the hopelessly complicated and near-singular focus of Beltway climate politics in the twenty-first century—is the only or the best way to deliver that.

For much of the last decade, the case for decarbonization has rested on a tantalizing win-win: that investing in lower-carbon industries of the future would at once deliver U.S. businesses a competitive edge in global markets, create millions of jobs, and “solve” climate change. But there is no solving climate change. However fast decarbonization might happen, that crisis—long imagined as some far-off threat to the United States—is already here, and worsening in ways that are leaving climate scientists flummoxed. It hasn’t arrived all at once as some biblical apocalypse but as a creeping drain on rents, utility bills, and grocery prices.

There’s no automatic relationship between people experiencing natural disasters and demanding “climate action.” But hurricanes, floods, and fires could be opportunities to organize the millions being displaced and bankrupted by the climate crisis into novel political coalitions around new demands. Whether those efforts are branded as climate politics or not, they will ideally be more concerned with improving the lives of people in a climate-ravaged country than with some imaginary coalition of green capitalists.

Evan Weber—the Sunrise Movement co-founder—had moved back home to Oahu by the time the Inflation Reduction Act eventually passed. After more than a decade working in Washington, Weber was grateful to be out of the Beltway, closer to his family, and working with a new organization, Our Hawai’i. “The stuff that we’ve been able to do here,” he said, “made me believe in organizing and social movements and people power and worker power again, when I was feeling kind of depressed about a lot of those things from my experiences at the national level.”

About a year after the IRA passed, in 2023, Hawaii faced America’s deadliest wildfire in more than a century, and—until Los Angeles caught fire last January—the most expensive. More than 100 people were killed on Maui, and the city of Lahaina was leveled. The Lahaina fires exacerbated a long-standing housing crisis in Hawaii. A recent report from the Economic Research Organization at the University of Hawai’i found that the state has the country’s highest home prices and second-largest median rents, after California. In Maui, rents over the last five years have risen by 37 percent more than the statewide average; after the fires, renters there reported paying as much as 60 percent more, driven in part by a spike in insurance premiums. Since 2023, Hawaii’s rate of homelessness has risen by 87 percent, to become the highest in the nation.

In response to this crushing affordability crisis, Our Hawai’i has backed a campaign led by local organizers with Lahaina Strong to phase out vacation rentals in areas of Maui that are zoned for apartments. Short-term rental properties—many owned by out-of-state landlords—make up 41 percent of housing stock in the areas worst-hit by fires. The bill, expected to come up for a vote in the Maui County Council this fall, could open up several thousand condos and other apartment-zoned units to become long-term housing for Maui residents.

“You might not think about that as climate policy, but it is,” Weber told me. “To survive all the calamities that the twenty-first century has in store for us, people need basic things like housing and health care.” While Hawaii’s affordability crisis is particularly intense, it isn’t unique: Over the last five years, the average cost of home insurance policies has risen by 30 to 40 percent nationwide amid a drumbeat of climate-fueled disasters, placing upward pressure on already inflated rents and home prices. As Republicans force states to shell out more for disaster relief, Medicare, and Medicaid, they’ll find it increasingly difficult to recover and prop up insurance markets with public funds.

To be sure, policies are desperately needed to decarbonize the grid and the production of essentials like steel and cement. But widening the aperture of climate politics beyond the relatively narrow, inscrutable confines of energy and electricity—to areas like housing—might just help build political support for it.

“Climate change is here to stay, and we have to do everything that we can to mitigate it,” Weber said. “But a lot of the way that people experience climate policy is not through how they’re fueling their cars or what they’re powering their iPhones with, but how they’re surviving the disasters that are going to eventually come to their doorstep.”