I.

I got the call a little before 5 p.m. on a Friday. My wife, Sima, and I were sitting on the couch with our kids, probably watching Curious George. The White House vetting process had gone on for months. Yet, despite the Zooms and document requests and endless online forms, I had a strange certainty that I ultimately would not be selected. “You’ve said … a lot of stuff,” observed the twentysomething staffer who got my file.

The end of the day Friday is when Washington takes out the trash. It’s when you push out the bad news so it’s old news by Monday’s news cycle. So when the call came in, I looked at my phone, looked at Sima, and dismissively said as I stood to take the call something like: “Ah. This is the White House saying they’re not picking me.”

Indeed, until the precise moment the words came out of the phone—“President Biden is going to nominate you to the Federal Trade Commission on Monday”—I remained convinced it was never going to happen.

But it did.

By that point, in September 2021, I’d spent most of my career working for two causes: privacy and immigrant rights. I stood up the Senate privacy subcommittee for Senator Al Franken and organized oversight hearings into Google and Apple and Facebook and the National Security Agency. I started the D.C. area’s first college scholarship that was blind to immigration status. As a law professor, I built a team that figured out how Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE, finds people it wants to deport by pooling and mining their gas, water, and electric bills. I also served on the board of CASA, an extraordinary immigrant rights group that calls Kilmar Ábrego García a dues-paying member.

I denounced the Trump administration’s decision to separate parents from their children at the border. I called ICE an “out of control domestic surveillance agency.” I even called the president a racist on social media.

I got confirmed by the skin of my crooked teeth. It didn’t matter that I had deep experience on privacy—a core issue in the FTC’s consumer protection work. No Republican voted for me in the Senate Commerce Committee. No Republican voted for me on the floor of the Senate either. Vice President Kamala Harris had to travel to the Capitol to cast a tie-breaking vote in my favor—three times.

One Republican senator told me why. We’d just had a long conversation about what social media was doing to teenagers’ mental health, and what I wanted to do about it. “I like you,” he said. “I look forward to working with you. But I can’t vote for you because of what you said about the president.”

I came into office an unabashed advocate for immigrants. I left office the same way. But while that hasn’t changed, after three years as a commissioner, the way I look at the world has. I used to think that the defining fight for our country was between the left and the right. Now, I am much more worried about the money at the top crushing everyone underneath.

That sounds grim because it is. But I also think this perspective can unite our country in a way that feels almost impossible today.

II.

When you are confirmed to the FTC, after you get your badge and keys and figure out your computer, the conference invitations start chiming in your inbox: Aspen, Brussels, Vegas, Davos.

I declined those invites. My first trip was to Charleston, West Virginia.

I had spent a lot of time during my confirmation process trying to teach myself about the pharmaceutical supply chain, and the way it affected pharmacies in rural and urban America. Along the way, I spent some time on the phone with Lynne Fruth, the second-generation owner of an independent pharmacy chain in Appalachia. She told me about how insurance companies were using intermediaries called “pharmacy benefit managers” to systematically steer lucrative prescriptions to their own mail-order pharmacies—not the ones that were convenient for their patients.

I later read a West Virginia state insurance commissioner’s report about a family who had almost been turned away from a local pharmacy. Their child was sick with cancer. The pharmacy had the right medicine in stock. But an insurance company middleman told them to go home and wait up to two weeks for the medicine to arrive in the mail.

So one night, after feeding the kids dinner, I got in my car and drove out to meet Fruth. As I left my house in Rockville, I turned on a podcast whose sole purpose was to explain the acronym soup of pharmaceutical pricing: “WAC,” “MAC,” “NADAC.” It got me well past Harper’s Ferry—more than an hour away.

The next morning, in an office park just outside of Charleston, a roomful of independent pharmacists told me about the bizarre “negotiations” with those middlemen. Any wins were made on the phone. But the middlemen could undo those concessions at any time via fax. The pharmacists described being “audited” by those middlemen. Somehow, they were always fined by those same middlemen for noncompliance. And now, drug reimbursements from those insurers were going through the floor.

In the pandemic, those independent pharmacists had vaccinated thousands of people, often in the poorest and most isolated areas unserved by national pharmacy chains. Their customers had heard all sorts of things about the vaccine online or on television. But they trusted their local pharmacists. Now, those independent pharmacies were closing, one after another. One pharmacist said, with a sad laugh, that he had started selling Jack Daniel’s just to keep the lights on.

Toward the end of our session, a retired accountant named Jim Rossi started to speak. He had joined the meeting at Fruth’s request. He ticked through his daily routine of 15 pills for nine medicines treating three autoimmune disorders and a heart condition that required a pacemaker.

He then told me what it was like to get all that via mail-order pharmacy.

“It takes about a week to resolve any kind of a small issue with them,” he said. “Then, it takes them another week to fill the prescription. Then after that additional week wait, they ship the medication to me.” That took another three days to a week. His specialist had warned him to stick with the same manufacturer for each prescription. That’s not what came in the mail. “I open up the bottle, and there are three different colors of pills in it, which tells me there’s three different manufacturers in that bottle.”

But there was one drug, for his Crohn’s disease, that the mail-order pharmacy filled unfailingly fast and in advance. He sometimes had a nine-month supply in a drawer at home. That one cost $1,000 a month.

My second trip on the job was to Des Moines, where I met with nine corn growers and cattlemen in a hotel conference room on the sidelines of a law enforcement conference. The session was organized by my adviser, Max Miller, who had just left a job as an Iowa assistant attorney general to join my staff.

This was the meat and potatoes of Max’s practice. I felt out of place in a suit and an N-95 mask.

That went away when they started talking.

Every person described a situation in which corporate power was squeezing them. They used to have any number of vendors to buy their seeds from; now there were two. The suppliers of all their inputs—feed, fertilizer, pesticides, you name it—had slowly consolidated and were jacking up prices. The ag industry was known for relentless innovation. “We doubled our yields in a generation,” the farmers said. But now, the companies weren’t focused on research and development. “They’re using their wealth to buy their competitors,” they said.

The ranchers used to have any number of places to process their cattle. Now, a lot of them had just one meatpacking plant accessible to them. When you have just one place to sell your livestock, no one competes to buy it. What the processor pays is what you get. They used to fix their own tractors. Now, John Deere locked down its software, forcing them to take those tractors to a company dealership.

“It’s like getting picked apart by a chicken,” said one of them. Said another: “We have a noose around our necks, and we’re standing on an ice cube.”

But the problem went beyond income. When there’s just one processor, you have to get to that processor regardless of how far it is. Cattle die in the heat of the drive. And when that processor closes—as many did during Covid—there’s nowhere else to take your livestock. One rancher had to gas his hogs, dig ditches, and hire high schoolers “to fill holes with dead hogs.”

Another rancher told me about how his one processor treated his animals. A cow had slipped upon arrival at the lot. She was injured and could not regain her footing. The rancher begged staff to let him take her home to heal, but that request was denied. No livestock could leave the premises. She was attached to a log chain, dragged out of the trailer, killed with a bolt to the head, and thrown in a dumpster.

One of the last places I visited as a commissioner was a community center in a small park in Miami’s Little Havana. It was after sunset in early April, but it was already 80 degrees and muggy.

Amid the sounds of creaking swings and little kids cutting their bikes through the playground, a dozen men trickled into the room after finishing construction and landscaping shifts in the Miami region, home to Jeff Bezos, billionaire hedge fund manager Ken Griffin, and over a hundred centimillionaires.

Most of them were in their twenties and thirties. They wore baseball caps and crisp T-shirts. They looked like they had gone home, showered, and walked into the room a few moments later. They were tired.

I expected their main problem to be that they didn’t get unemployment insurance, workers’ compensation, or overtime. And I was right to a point. They didn’t. Even though they showed up at work and did what they were told, how they were told, and when they were told to do it, their bosses deemed them “independent contractors”—independent business owners, not W-2 employees. (I later heard an interview with an organizer who said he met workers who didn’t even know what overtime was—they’d never heard of it. “No saben que cosa es ‘overtime,’” he said.)

But that wasn’t their main complaint. Their main complaint was that they didn’t get water. I did not expect that.

“Maybe there’s a thermos that’s filled with water that’s not potable,” said an organizer from WeCount!, the group that called the meeting. “Maybe there’s a thermos that’s covered in mold.” One of the men worked for hours in over 100-degree heat while staring at a cooler—his only source of bottled water. The cooler was locked.

The prior year, a 47-year-old worker had died while remodeling a multimillion-dollar home in Coral Gables. The heat index was 104. A Tampa Bay Times investigation found that 37 outdoor workers died from heat-related causes in Florida over the past decade, “some just hundreds of feet from air conditioning and running water.”

Federal safety inspectors were nowhere to be found. “There’s no water. There’s no harness training. We’ll go a month without the most minimum contact with OSHA”—the Occupational Safety and Health Administration—said a painter named Ronny.

What if he complained to his employer? Most of the workers were undocumented, Ronny explained. “When you ask for the law, you lose your job.”

So, the workers had gone to the county commission, and they succeeded in securing the passage of a law mandating water breaks for local construction sites. Six days after we met, Republican Governor Ron DeSantis blocked the ordinance.

My second-to-last trip was to New York City, where I met with rideshare drivers gathered in a lecture hall at Fordham Law School near Lincoln Center. There were about 20 or 25 of them. They described being lured by promises of lucrative earnings accompanied by near-total control of their schedules. Many of them invested tens of thousands of dollars in new vehicles so they could get the best fares.

A lot of them had a good experience; some had had it good for years. But recently, the apps started locking them out at seemingly random times of day.

The first driver I heard from was named Mohamed Mohamed. He had maintained a five-star rating and a 100 percent acceptance rate over 21,000 rides and nine years of driving. At the start, he liked that the companies called him a “partner.” “You’re a partner for us,” he recalled them telling him.

Now, “I take three trips, I stop to go to the bathroom, and I’m locked out for the end of the day,” he said. He was in $2,000 of credit card debt. And he now had to drive 12 hours to earn what he previously earned in four.

Then another driver sat down to speak. I didn’t catch his name; I noticed he was shaking. His wife had died unexpectedly that morning. But he had been inexplicably kicked off the apps altogether with no explanation. He showed up anyway, because someone in government was finally going to listen to him.

“This is not fair,” he yelled. “And I need the account back on to go to work. Because the city provided me a license to work, to be a good citizen. I am.” He was crying. “I do everything. Pandemic, I work. Snow, I work. Why I cannot live like a decent people?”

The despair in this country is far deeper than most of us understand. It’s worse than that, actually: It’s so pervasive that we don’t even see it. It’s become normal.

In the wealthiest country on Earth, it’s normal for people who are diagnosed with cancer to set up a web page to beg their friends and family for money. It’s normal for those people to go bankrupt. Getting sick is the most normal reason to go bankrupt.

In a country that celebrates farmers, it’s normal for those farmers to kill themselves at a rate far beyond the rest of the population.

At a time when billionaires compete to launch rockets into space, it’s normal—completely normal—for construction workers to die of heat and thirst.

Many liberals remain baffled that America elected Donald Trump. They genuinely have no idea how he could have won the election. I don’t think that Trump won because of “wokeism” or the “trans agenda,” whatever that is. I think he won by speaking to that despair and telling people that he alone could fix it.

His tirades against China and “illegals”? Some people listened to them and heard bigotry and xenophobia. I heard it, too. But more people heard a guy talking about how he was going to help them make rent. At least enough people to win the election.

III.

My time as a commissioner changed the way I saw things.

I always suspected that despite Trump’s promises to cap credit card fees and slash prices and bring manufacturing back home, all of it would more or less amount to nothing. So far, other than temporarily reducing taxes on tips, that’s pretty much what’s happened. Instead, we face looming health care and childcare cuts for millions, a slowdown in manufacturing, and on-again-off-again tariffs indexed to whether a country will nominate Donald Trump for a Nobel Prize. Chaos and cruelty don’t pay the rent.

But I expected all that. What I did not expect was that over time, people I’d seen as bold progressives started to look quite different.

I always thought of Colorado Governor Jared Polis as a pathbreaker: the first openly gay man and first Jewish person elected governor in the state. Now, all I can think about is how he vetoed a law that would make it dramatically easier for people in Colorado to form a union … and a law that would have barred landlords from using algorithms to collude on rent hikes … and a law, passed unanimously in the state legislature, to end surprise ambulance bills … in two weeks.

I always liked how Illinois Governor JB Pritzker stood up for the little guy: for undocumented people, for trans kids. I love how he seems genuinely unafraid of this president. But it’s harder to see him in the same light after watching him veto a bill that would have protected workers at Amazon warehouses—where injuries are so frequent that the company puts vending machines on its warehouse floors that dispense not potato chips, but painkillers. Why can’t Pritzker fight for the people in warehousing?

Perhaps my biggest change is in how I think about what’s happening with ICE. The masked police, the flash renditions, the swamp gulag—we now live in the dystopia that we were loudly warned about during the president’s first term.

But when I see police tackle a teenager with a baby’s teething toy in her hand, when I see them peel a child off of her dad’s arm at the courthouse, or cuff a shrieking mother saying she needs to get her kids from school, my first thought is not to “immigrant rights.”

No. Now, I can’t stop thinking about the lawyer in a hand-stitched suit sitting at my old FTC conference table, telling me, over 70 minutes and a 30-page PowerPoint, how it could not possibly be in the interest of the United States government to sue her corporate client. And I’m not talking about one particular case; I’m talking about all of them. When the federal government does things like investigate a corporate landlord for packing rent checks with fake charges, or an oil executive allegedly trying to “align U.S. oil production with OPEC,” or pharmacy middlemen accused of trying to raise the price of insulin—it’s sternly worded letters, PDF white papers, and multiple hour-long meetings where the company gets to tell us what we got wrong. That’s standard process.

But when you’re a cleaning lady whose papers aren’t right? It’s five men in bulletproof vests on your doorstep, and your four-year-old crumpled in your arms begging “no quiero please, please, please.” It’s an agent saying, “I’m sorry, but I don’t have any choice.”

And that difference enrages me.

Soon after taking office, Trump’s designated chairman of the FTC, Andrew Ferguson, announced that the agency would “usher in a new Golden Age for American businesses, workers, and consumers.” What has followed has been a Golden Age for the C-suite. The ban on noncompete clauses that keep everyone from pediatric surgeons to Jimmy John’s sandwich-makers in dead-end positions, or keep them from working entirely? Not worth defending in court. The rule banning companies from doing that thing where they sign you up for a subscription online, but only let you unsubscribe over the phone? Enforcement delayed to mid-July to give companies “ample time” to comply … and the federal court a window to strike it down. The order barring that oil executive from the board of Exxon? Undone. He’s free and clear to join.

A similar scene unfolded 10 blocks west at the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. The bank that was systematically hitting service members with surprise overdraft fees and forced to send them $80 million in refunds? Don’t have to pay them back anymore. The lawsuit against a Berkshire Hathaway subsidiary that allegedly tricked people into taking out loans for mobile homes when they had $57.78 in discretionary income? Gone.

As everyone knows, these are just the lowlights. What people may not know is how thoroughly unprepared we are for this reality.

Picture the inauguration. If the president tries to illegally deport you or illegally strip you of your voting rights or (ahem) illegally fire you, there are dozens of nonprofits that can step up to defend you in court, free of cost. Many struggle to make payroll. Some have tens of millions of dollars in the bank. The American Civil Liberties Union has $829 million.

But what if the billionaires over the president’s shoulder hurt you? If they use legal loopholes to deny you health care? If they dock or block your pay for no apparent reason? If they buy all of your buyers so that only they buy your goods, and they set the price? If they use their market power not to outcompete you, but to bully you out of the market?

There are maybe a handful of national nonprofit organizations that will represent you pro bono. And the ACLU fights the government, not the oligarchs.

This all-encompassing focus on fighting government overreach may have made sense when our tax system actually taxed the rich, when union membership was at an all-time high, and when CEO earnings were not a vulgarity.

Now, Fortune 500 firms regularly pay zero dollars in taxes. Unions protect just one in 10 workers. And CEOs parade like modern-day Roman emperors, in private jets, to private islands, with their private Praetorian firefighters and guards. And all of this is happening when the government agencies built to check corporate power are being torn apart.

IV.

My daughter likes me to watch her gymnastics class. Let me try that again. My daughter really doesn’t like it when I stare at my phone during her gymnastics class. She has her mother’s strength. So when she makes it around the uneven bars a little faster than her peers, the first thing she does is shoot me a look. If I’m looking at my phone, that’s a big “L” for dad.

And so, on a Tuesday this March, when I got a call a few moments after arriving at the gym from my colleague, Commissioner Rebecca Kelly Slaughter, asking, “Hey, have you checked your email?”—I proudly said I had not!

“Well, I just got an email from the White House saying they were firing me. You should probably check yours.”

Sure enough, I had an email from someone named Trent Morse informing me that the president was firing me, effective immediately. Curiously, Morse did not claim I had neglected my duties or misused my authority; he went out of his way to not give a reason for the firing. That was a problem—for them. Because the Supreme Court had said, 90 years earlier, that the president could only remove an FTC commissioner “for cause.” The court said that unanimously.

Suddenly, we had to answer a really weird question really quickly: If the president says you’re fired, but the Supreme Court says he can’t fire you, did you get fired? Or did you not get fired?

Becca and I decided we did not get fired. We would keep doing our jobs. We’d keep on taking meetings, issuing statements, testifying before Congress. And we thought we should be loud about it.

I called Sima, and my chief of staff. Then I put out a statement saying that the president was trying to turn the FTC, a fierce corporate watchdog, into “a lapdog for his golfing buddies.” The calls started. The New York Times, Bloomberg, a producer for Chris Hayes. My daughter got out of class, and I told her I’d been fired. She gave me a hug, got in the car, and asked if she could watch her favorite Lego builder on YouTube.

FTC staff started calling. Then, more reporters. Ten minutes into the drive home, a little voice in the back seat piped up, “Papa, why are we going this way?” I was missing turns from the notifications on my screen, then missing more turns when my phone, which kept on dinging, was slow to update the map.

When we finally got home, I recorded a video to explain how this wasn’t about hurting me, but about helping the men at the inauguration—Musk, Bezos, Zuckerberg, Pichai. Between the two of us, Becca and I had sued, or were actively suing, each of the men’s companies. And we were weeks from a federal trial against Meta. We did a virtual press conference with some senators and congressmen; I did more interviews after that.

A little before midnight, there was a knock at our door. Domino’s. It was my first break since 5 p.m., and I was grateful for what I thought was a gesture from a friend who knew I’d be up late.

I opened the box: meat lover’s, loaded with bacon. We don’t do bacon. I asked the delivery guy if he’d gotten a tip—he said no—so I started trying to find an app to pay him, when he spoke up to say, “Well, ah, sir, you still haven’t paid for the pizza.”

That’s when we realized that the pizza was not from a friend. It was from someone, somewhere, telling me they knew where I lived.

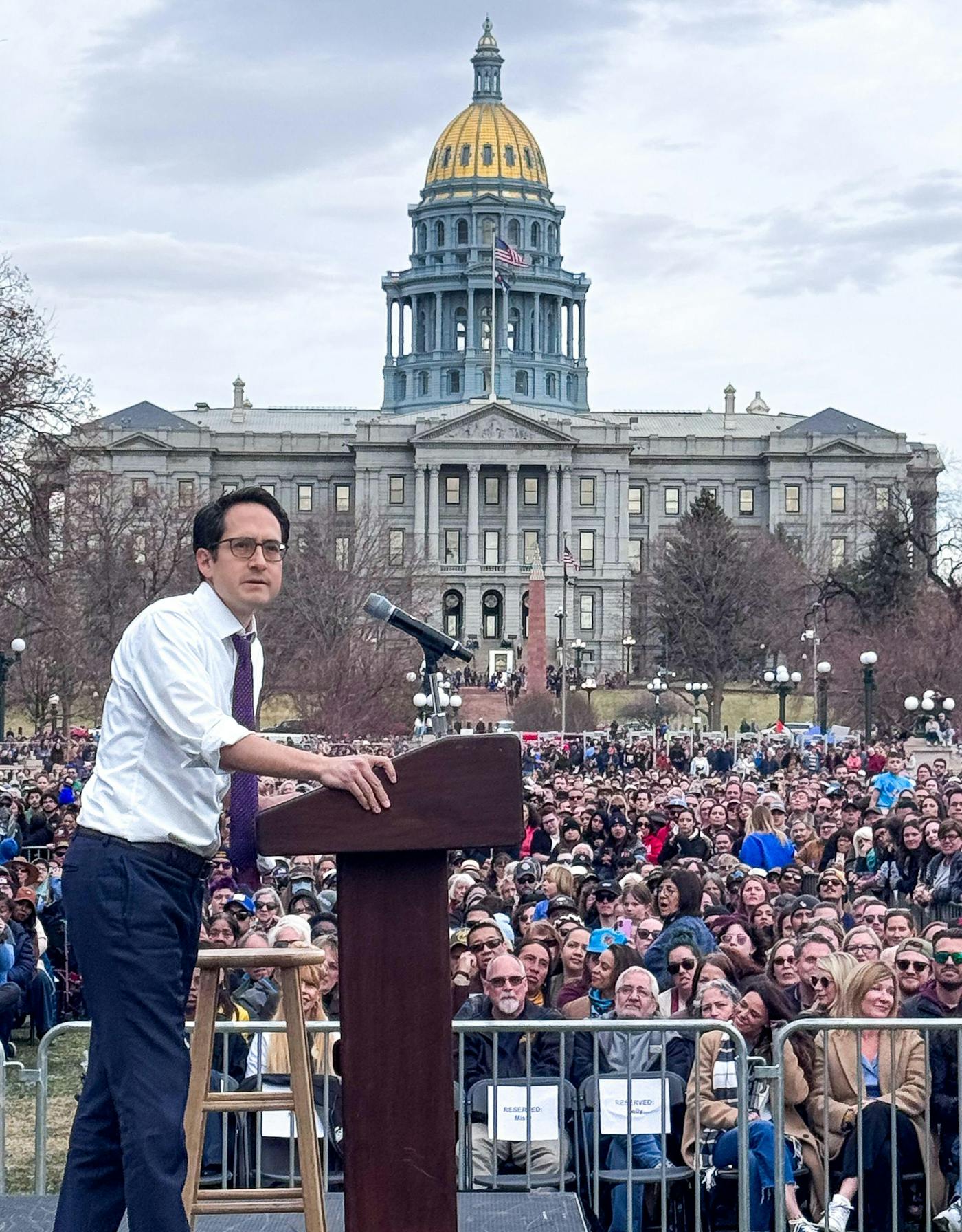

The days and weeks ping-ponged between the thrill of being able to publicly denounce what was happening to our agency—and the dull fear a parent feels when things are not right for their family. I hold virtual roundtables with rideshare drivers in Denver, fishermen from Maine, and small retailers in Massachusetts—someone tries to take out a half-million-dollar line of credit in my name. I speak at the Bernie and AOC rally in Denver; I scream so loud I pull a muscle in my neck. I realize we can’t buy a house on a single income, even though we’d been planning a move for months.

Commissioner Slaughter and I quickly sued to block the attempt to remove us. The financial ramifications of the legal fight started to set in. Sima and I looked at our accounts and figured we could afford about three months for it to play out. The three-month mark approached with no ruling from the judge. So I decided to call the guys in Iowa.

My very last visit as a commissioner was to a family farm in Ankeny, just north of Des Moines. It was scheduled for a Saturday morning in June. Going in, I knew that by Monday, unless I woke up to a ruling reinstating me, I’d issue a statement formally resigning as a commissioner, letting me start to look for a new job.

Max, my former adviser, put me up at his house the night before. We woke up and went to the farmer’s market with his new wife and their now five kids. I got a coffee and a kielbasa. We drove up to Ankeny.

The Iowa Farmers Union had organized a listening session at a fifth-generation diversified farm that grew corn, soybeans, oats, and alfalfa, along with a range of livestock. The owner, LaVon Griffieon, had attended that first meeting; so had a few others in the audience.

This time, I was able to talk about our lawsuit against two pesticides manufacturers that were trying to push cheaper generics off the market, as well as about our lawsuit, filed just that January, against John Deere for locking down its software.

The group was kind to me. They appreciated it, they said. But so many of their stories were the same that they were three years earlier. A corn and soybean grower said that fertilizer prices were moving in lockstep, such that the moment the farmers finally saw some profit, prices would go up and erase those profits. “Iowans like to claim they feed the world,” said Griffieon. “But the pandemic proved to us with bare store shelves that Iowa can’t even feed Iowa very easily.”

A half-hour in, there was a speaker I hadn’t met—a tall, young farmer with long hair, also fifth-generation, named Sean Dengler. On the first day of the winter harvest, he had gotten up and turned on the combine. It roared, then whimpered, then went into “limp mode.” The circuit board was fried, and only John Deere could fix it.

Sean’s father called the dealership right away, but the technician took hours to get there. A line of other farmers had called in first. The soybeans were already dry, and it was hot and windy. So they paid extra for the part to be delivered the next day; and again paid extra for the second visit. “We lost time waiting, which meant lost yield potential,” he said. “And we lost money because John Deere could charge us more because that is their business plan.”

Our lawsuit was a few months too late. It was Sean’s last harvest. “Both of my grandparents were farmers,” he said. “I’m the last Dengler to ever farm in Tama County.”

The session lasted another hour. I had lunch at a Mexican restaurant with the union president, his vice president, an ag reporter, and Josh Manske, a board member from Algona, Iowa. The lunch lasted about an hour. And that was it. I was done.

Josh and I met Max in a park back in Des Moines, got some beers, and found an empty picnic table. We talked about Max’s blended family. I thanked Josh for hosting a liminal FTC commissioner. We laughed about that.

We talked about the session. While a lot of things had come up, I kept coming back to Sean Dengler. Then, I thought about those rideshare drivers in New York City. It may not look this way at first, but the Iowa farmer who can’t run his combine because of a farm equipment monopoly has a heck of a lot in common with the Bangladeshi dad who can’t work the morning commute because he’s locked out by Uber and Lyft.

If you focus on the conflict between left and right, if the most important thing is what you are—your party, your state, your race, your ethnicity—the people I met could not be more different. On the one hand, you have rural, white small-business owners, generations into building a life in this country. On the other, you have urban Latino, Haitian, African, and South Asian immigrants, every one of them a worker. The line between them is sharp, almost tribal. What could they possibly have in common?

Everything—if you look at what they need. The people I met as a commissioner may look different, but what they need is surprisingly the same: They need a government that gives them a level playing field against the powerful and wealthy. They need the courts to check corporations when they abuse that power and wealth. They need basic dignity and control in their material lives.

Looking at things that way, everyone I met was part of one huge group: people working themselves to the bone who were getting screwed by billionaires and corporations—regardless of party or state or race or ethnicity. Regardless, even, of whether they are workers or the owners of farms or small businesses.

Populism is not an indictment, but an opportunity. Focusing on the conflict between the haves and the have-nots is not divisive; it’s a way to build coalitions with astonishing potential.

Our nation’s first antitrust law was passed at the demand of small farmers bled dry by the railroads and grain elevators. But when Ohio’s John Sherman stood on the floor of the Senate to call for its passage in 1890, he didn’t just do it for the Grangers. He also talked about labor. The trust “commands the price of labor without fear of strikes,” he declared, “for in its field it allows no competitors.”

When the law was abused to crack down on strikers, Samuel Gompers mobilized the American Federation of Labor and won corrections in the 1914 Clayton Act to try to guarantee them that right, while tightening other loopholes that John Rockefeller and the other robber barons had exploited. Gompers called the law a “Magna Carta for labor.” Then in 1936, small-town grocers came in to press for and win a separate law to stop the incipient A&P grocery chain—ancestor of the modern big-box stores—from cutting secret deals with their suppliers that slashed prices for A&P while marking them up for the little guys.

Our anti-monopoly laws exist because of the work of farmers, labor unions, and country grocers. If that seems like an unlikely bunch, consider that Minnesota still does not have a “Democratic” party, but rather a Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party, because of a resurgence of that coalition 30 years after the Sherman Act.

Consider that the pharmacy deserts in Appalachia are caused by the same ruthless middlemen who create those deserts in Philadelphia. I know, because a session I had with the Philadelphia pharmacists was nearly identical to one I’d had in Charleston. The same goes for independent grocers. The people in Pine Ridge, South Dakota, live in an incipient food desert for the same reason that the people of downtown North Tulsa do: The government stopped enforcing the 1936 law (it was called the Robinson-Patman Act). And when we start enforcing it again, poor people in small towns and big cities—people told every day that they have nothing in common—will benefit in equal measure.

I feel the potential for those fights anytime I hear how some conservatives talk about the tenure of Lina Khan, whom I served alongside when she was chair of the Federal Trade Commission. I felt it when I talked to people about my job.

I had a favorite kind of conversation as a commissioner. I had some version of it at least three or four times. It was when a MAGA conservative asked me—a certified “left-wing activist,” “provocateur,” “bomb-thrower,” and “extremist”—to quote my friend Ted Cruz: What exactly is it you do in government?

I would tell anyone who asked that I was investigating the pharmacy middlemen who were shutting down independent pharmacies across rural and urban America. I’d tell them I was suing Amazon for screwing over small retailers. I’d tell them I was making sure that the biggest grocery store in town doesn’t buy the next biggest grocery store in town—which will make eggs even more expensive and union negotiations even harder. I’d tell them I was trying to let gig workers organize so that Uber and Lyft and DoorDash couldn’t lie to them or cheat them out of their pay. I’d tell them I was suing landlords who pack rent bills with hidden fees. I definitely told them that we were trying to end that horrible thing where you sign up for something online but can only cancel on the phone before 4 p.m., after 45 minutes on hold.

And usually, by that point, the conversation had changed. Their suspicion had turned into cautious interest, maybe even excitement.

V.

Undocumented people have become the new American underclass: good enough to pick our crops, bus our tables, and build our buildings—not good enough for us to protect their life or liberty, let alone their pursuit of happiness.

There are many reasons for this. Some are legal. A lot of it is anger.

I understand where some of the anger comes from. Take the construction industry. A generation of working-class kids grew up watching their dads provide for their families by working construction. They were hard jobs, but they were good ones. You could buy a house, send your kid to college, maybe even buy a boat for the weekends. Now, those jobs pay a fraction of what they used to. And those kids are now adults, voting adults, and they see those jobs occupied by men from Central and South America, many of whom are undocumented.

What would it look like to confront undocumented immigration not as a left-right issue, but as a conflict between billionaires and working people?

Maybe we focus less on the tension between undocumented people and the native-born workers that they seem to displace. Maybe we focus more on the billionaire developers who pretended that the people they hired were “independent contractors,” turning what used to be middle-class jobs into subsistence work, while also making it easier to hire and exploit undocumented laborers.

Maybe we ask ourselves: Who gets rich from that? Is it the guy working in 100-degree heat with no water? Or is it the guy downing a steak while toasting his new development? Maybe we try to become skeptical of the idea that the least powerful people are the most responsible for our problems. Maybe we punch up instead of punching the neighbor.

Nowadays, I think a lot about what’s happened to Ábrego García. The media has rightly focused on the outpouring of support for an apprentice sheet metal worker and his young family in Beltsville, Maryland. They are right to focus on the courthouse protests. They made a difference.

But I have been moved by a different scene, which occurred in early April in a Washington, D.C., conference hall filled with electricians, ironworkers, and other tradespeople, members of the North America’s Building Trades Unions, where Ábrego García’s union is an affiliate. In this scene, NABTU president Sean McGarvey stands in front of his members, and says:

We need to make our voices heard. We’re not red, we’re not blue. We’re the building trades, the backbone of America. You want to build a $5 billion data center? Want more six-figure careers with health care, retirement, and no college debt? You don’t call Elon Musk. You call us! [...] And yeah, that means all of us—all of us! Including our brother, SMART apprentice Kilmar Ábrego García, who we demand to be returned to us and his family now.

He slams his fist on the podium. “Bring him home!” he shouts, as the audience gets out of their seats for a standing ovation.

And that, to me, feels like the future.