Not so long ago, originalism seemed safely contained. Ascendant during the Reagan era, originalists argued that the Constitution should be interpreted according to its original meaning, but when liberals dominated the Supreme Court, not many people outside of the academy felt the need to pay much attention. Still, the academic debates were revealing. Legal scholars both for and against originalism quickly found themselves debating questions that history professors might discuss with their undergraduates the first day of class—like, original meaning according to whom? In the case of the Constitution, the problem isn’t simply that its 55 Framers understood key clauses differently; it’s that the tens of thousands of ordinary Americans who publicly debated the document during the ratification process understood the text to mean different things, too. To paraphrase the historian Jack Rakove, there was never a single original meaning, only original meanings.

Most originalists today would say they adhere to an “original public meaning”—interpreting the document as it was understood by the broader public, not just the Framers. But this hardly clarifies things. Which public are we talking about? The people formally allowed to vote for delegates at state ratification conventions, which up until Reconstruction mostly meant white men? And what sources should we use to discern “public meaning”? Should we focus on pamphlets advocating for the Constitution’s adoption, like the Federalist Papers, which cast the document in the best possible light? Or should we put more trust in its staunchest critics, the Anti-Federalists, who, ironically enough, were largely responsible for the Constitution’s best-known parts: the first 10 amendments, or Bill of Rights, which include protections for freedom of speech and the right to bear arms.

All these debates might have been confined to law journals and classrooms were it not for the fact that we now have a Supreme Court dominated by conservatives, most of whom subscribe to some form of originalism. The response of many liberal pundits has been, as it often has, to argue that originalism is just conservative politics masquerading as history. But a few legal scholars have argued that liberals should embrace originalism themselves. Since the 1990s, Akhil Reed Amar, a law professor at Yale, has been the most prominent liberal scholar to take this view, and, in a series of popular histories since then, he has argued, either implicitly or explicitly, that a careful reading of the Constitution’s history would support many liberal outcomes.

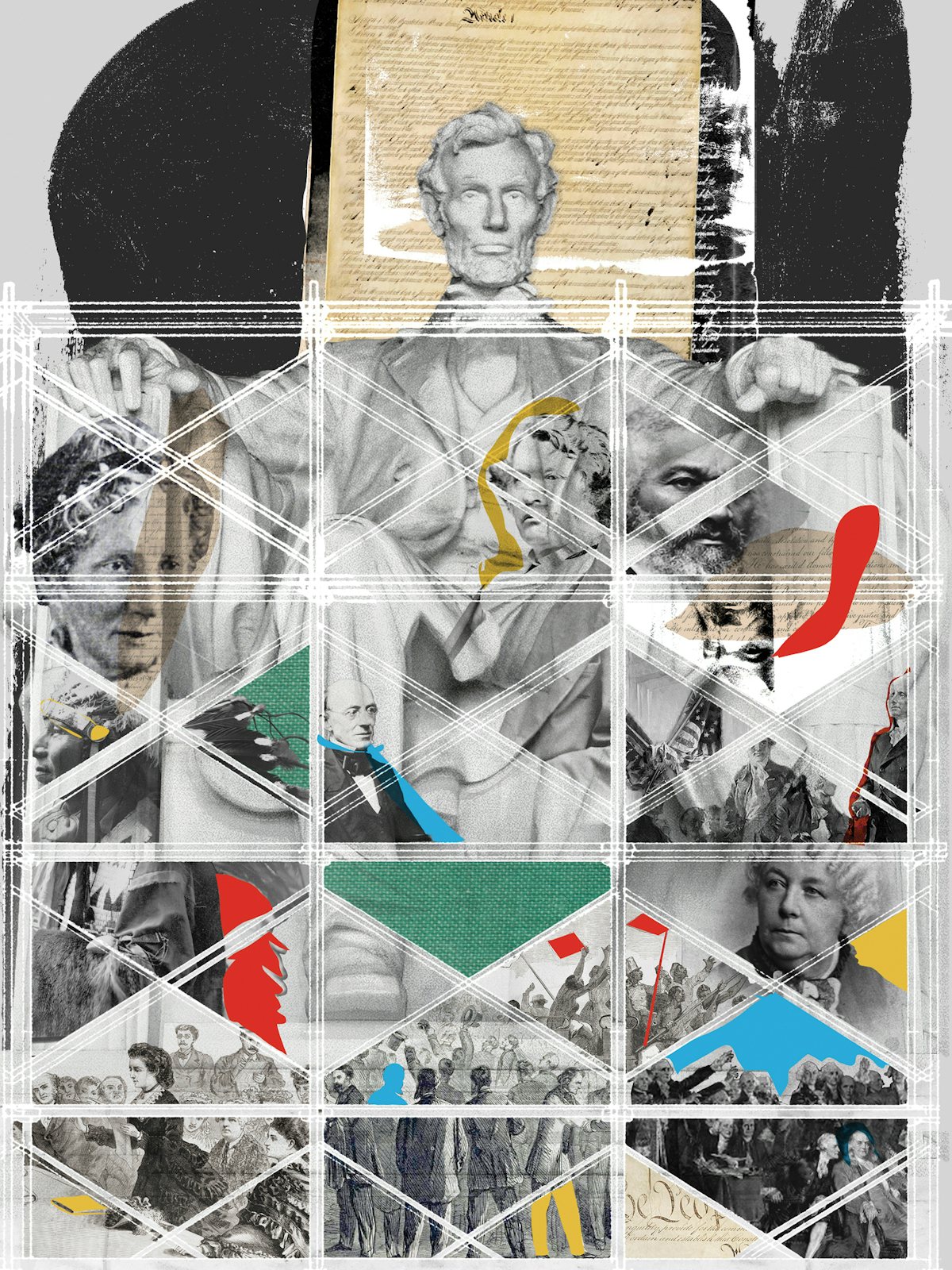

In his latest, Born Equal: Remaking America’s Constitution, 1840–1920, the second in a proposed trilogy on the Constitution’s history, Amar traces the origins of the Reconstruction amendments—the Thirteenth Amendment, abolishing slavery in 1865; the Fourteenth Amendment, establishing birthright citizenship, due process, and equal protection in 1868; and the Fifteenth Amendment, granting Black men the vote in 1870—along with the Nineteenth Amendment, which extended suffrage to women in 1920. His central argument is that these amendments succeeded because their advocates framed them as fulfillments of the nation’s founding texts, above all the Declaration of Independence’s claim that “all men are created equal.” By rooting their arguments in the Declaration and interpreting the Constitution as the Founders supposedly intended, figures like Lincoln—the book’s central hero—emerge as the first true “originalists.”

Amar’s message is hardly subtle: Liberals and progressives who try to advance equality by dismissing the Founders and the Constitution misunderstand history. The nation’s greatest strides toward equality haven’t come in spite of the Founders’ words, he suggests, but through liberals’ fidelity to them. That’s a debatable claim on legal terms, but is it even good history?

In Amar’s telling, the Declaration of Independence—250 years old this year—is the truest expression of the Founders’ ideals. Language from its soaring preamble was quickly appropriated for new state constitutions written during the American Revolution. On the eve of the Civil War, most Northern states had adopted some version of its assertion that “all men are created equal” in their constitutions, and Northern judges and lawmakers often cited this legally binding language to justify gradual emancipation. When Lincoln invoked the Declaration to validate his anti-slavery policies, as he did throughout his career, he was not breaking with the nation’s Founders but, Amar contends, standing on their shoulders.

Amar is right that Lincoln and his successors embraced the Declaration’s language to defend emancipation and equal citizenship. But he obscures the differences between the Declaration, Northern state constitutions, and the U.S. Constitution. The Declaration was nothing like the Constitution: It did not create a government, carried no legal force, and was written primarily to win foreign support in the war against Britain—nothing more. By adopting the Declaration’s egalitarian language, Northern state constitutions did lend them the weight of law. But historians as ideologically diverse as Gordon S. Wood and Woody Holton agree that it was precisely the radicalism of those state governments that the Constitution’s Framers sought to quell.

In the 1780s, Northern states began to abolish slavery and enfranchise landless whites and free Black people. But most worrisome to the Framers was their populist economic agenda, which included tax holidays, rent freezes, and paper money issuance. It was precisely these democratic impulses—inspired by the Declaration—that the Framers sought to contain in 1787. Far from simply strengthening the Articles of Confederation, they wanted to curb what one Framer called the “excess of democracy” unfolding at the state level. Yet even as these Northern states invoked “Declarationist” language and outlawed slavery, many soon barred free Black men from voting, and Midwestern states prohibited free Black people from entry. By casting the Declaration, Northern state constitutions, and the Constitution as of a piece—when in fact they were often at odds—Amar ignores their radically different historical contexts and ends up miscasting Lincoln. He wasn’t an “originalist,” faithful to their original meaning: He was creatively reinterpreting them to meet the time’s needs.

Born Equal is on firmer ground in narrating the ways antebellum anti-slavery politicians hewed closely to the Constitution. To his credit, Amar doesn’t argue that the original Constitution was inherently anti-slavery. Instead, he maintains that, despite its many pro-slavery features, it had just enough Easter eggs for future anti-slavery politicians to utilize. The Adams family—beginning with John Adams, an overlooked co-author of the Declaration of Independence—figures prominently in Amar’s account. He credits his son John Quincy Adams, a former president and, in the 1830s, a leading anti-slavery voice in Congress, for realizing that the Constitution could allow the federal government to emancipate slaves during wartime—the justification Lincoln used for the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. Because the Constitution never formally recognized slavery under federal law, and because its purpose was to provide for the nation’s “common defense,” the federal government could emancipate slaves as a wartime necessity, or so argued Adams and eventually Lincoln. Amar sees this as sound originalist reasoning and cites founding era politicians who warned about this very thing. During Virginia’s ratifying convention in 1788, Patrick Henry, who opposed adoption of the Constitution, cautioned that, in a future war, Congress could “liberate every one of your slaves.”

Charles Francis Adams, John Quincy Adams’s son, would continue in his family’s footsteps. As the 1848 vice presidential candidate for the new Free-Soil Party, the predecessor to the Republican Party, he announced he would abide by what became known as the Constitution’s “federal consensus”: respecting slavery at the state level but allowing management of slavery at the federal level. For an anti-slavery party after the Mexican-American War of 1846 to 1848, that meant preventing slavery’s extension into the newly acquired Western territories—not abolishing slavery in Southern states where it already existed and not giving freed Black people citizenship or voting rights. This became the Republican Party platform before the Civil War, and, like Lincoln, Adams framed it as rigorously constitutional, and essential to “the maintenance of the fundamental doctrines of the Declaration of Independence.”

For Amar, sincere constitutionalism was crucial not only for the Free-Soil’s and Republican Party’s electoral successes, but for wartime emancipation and the Reconstruction amendments that followed. He has little patience for the Liberty Party, founded in 1840 and supported by abolitionists and early suffragists like Elizabeth Cady Stanton. By 1848, what distinguished the rebranded National Liberty Party from the more popular Free-Soil Party was not just that the Liberty Party had more radical views, even flirting with women’s suffrage, but that it ran roughshod over the Constitution. If the United States had a Constitution “under which it cannot abolish slavery,” the National Liberty Party platform declared, in 1848, “then it must override … its Constitution.”

On originalist grounds, Amar is similarly skeptical of more radical Republican officials and abolitionists, like Charles Sumner and Frederick Douglass. These men showed no evidence that they had “truly taken seriously various pro-slavery features of the Constitution, such as the Fugitive Slave Clause,” which required free states to return runaway slaves. Before the war, some Republicans and many abolitionists pointed to the Fifth Amendment—which stated that no person could be denied “life, liberty, or property” without due process—to argue that the Constitution already prohibited slavery in federal territories, and entitled fugitive slaves caught in free states to a jury trial. Some even argued it inherently outlawed slavery nationwide. Lincoln rejected these views because, among other reasons, the Fugitive Slave Clause clearly suggested otherwise, and, Amar writes, “Abe was plainspoken. Honest. And avowedly originalist.”

Amar is even more harsh on the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, for obvious reasons. Four years after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which put federal muscle behind the Fugitive Slave Clause, Garrison famously called the Constitution a “covenant with death” and publicly burned the document on July Fourth. It was this kind of anti-constitutionalism, Amar argues, that turned “abolitionist” into a dirty word, forcing politicians like Lincoln to keep their distance.

Amar is right that Garrison’s anti-constitutional theatrics were alienating, but they were alienating to fellow abolitionists, too. That’s why the bulk of them, Black and white, chose to embrace party politics and couch their arguments in constitutional terms. Yet rather than explore the ways politically oriented abolitionists influenced the “constitutional conversation,” as Amar calls it, he draws a sharp line between faithful “originalists” like Lincoln and abolitionists and more progressive politicians, who were often more creative constitutional thinkers. And strangely enough, their ideas, far more than Lincoln’s, ended up shaping the Reconstruction amendments. That’s true even for Garrison. As Eric Foner has shown, since at least 1832, Garrison argued for “equal protection” before the law in the pages of The Liberator—and it was this precise language that, 36 years later, became embedded in the Fourteenth Amendment.

Throughout the antebellum period, free Black Northerners held annual Colored Conventions to advocate for birthright citizenship and Black male suffrage. They sought to overturn discriminatory state-level “Black Laws,” almost always framing their arguments in constitutional terms. “The United States Constitution … was framed to support justice,” declared a pamphlet published by Ohio’s Colored Convention in 1851, citing the Constitution’s preamble, which required the government to promote the “general welfare.” Several authors of the Reconstruction amendments had worked directly with free Black Northerners on these state-level civil rights campaigns before the war, and, as Kate Masur, Martha Jones, Van Gosse, and Christopher Bonner have shown, they drew on this experience when drafting their constitutional revisions.

The point isn’t that Amar should have merely included more abolitionists and ordinary Black people. Nor is that Lincoln was unimportant—his support was essential to the amendments’ passage. It’s that he misunderstands how much more those amendments reflected the innovative constitutional ideas of prewar abolitionists and free Black Northerners than they did the conventional constitutionalism of Lincoln and the bulk of the Republican Party.

Amar has been criticized before for not taking seriously “social history”—how ordinary people shape history. And he is anxious to make amends, though his efforts to include women and Native Americans still leave one wanting more. In a more than 700-page book with 17 chapters, Amar gives us one chapter on how women suffragists at the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention modeled their Declaration of Sentiments on the 1776 Declaration; part of a chapter on Harriet Beecher Stowe’s anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin; and a final chapter synthesizing the scholarship on why it took so long for the Nineteenth Amendment to pass. There’s also a two-page discussion of the Ponca Chief Standing Bear, who in 1879 fought, only briefly successfully, to attain citizenship under the Fourteenth Amendment, which explicitly barred Native Americans enrolled in tribes.

The problem isn’t a lack of representation—it’s that Born Equal reduces inclusion to tokenism. No one doubts Amar is a sharp legal mind, but is it being put to good use when the most we learn about why Stowe matters to the Constitution is that her novel popularized anti-slavery ideas, and in so doing “shaped America’s constitutional conversation as no woman had previously done”? That’s it? To his credit, Amar doesn’t shy away from ways the Reconstruction amendments and the Nineteenth Amendment perpetuated inequality—the Thirteenth had a loophole allowing “involuntary servitude” as punishment for a crime; the Fourteenth barred most Native Americans from citizenship; the Fifteenth excluded women; and the Nineteenth, in practice, excluded most Black women in the South.

But he is so relentlessly Whiggish that these facts appear as mere blemishes, and he never grapples with what has become a central concern of Reconstruction historians: Why did the same Republicans who used the Constitution to abolish slavery and grant Black Americans citizenship also use it to abrogate treaties with Native nations? Amar notes the Indian land theft that occurred during Reconstruction, but he does not engage with what historians have stressed for two decades: Slave emancipation and Native removal were intertwined in what is now called “Greater Reconstruction.” In the West, the Fourteenth Amendment dangled citizenship and equal protection at the price of tribal affiliation, with the ultimate aim of dispossessing Native peoples—granting membership in the United States in order to take away tribal sovereignty. In the South, the goal was to subdue slaveholders and integrate Black and white Southerners as full citizens. Binding it all together was a shared vision held by most liberal Americans, including Lincoln: the creation of a capitalist, consolidated—and racially diverse—nation-state under federal control.

Born Equal also falters on its grasp of political economy. Several times Amar suggests slaveholders should have recognized the “unsustainability” of slavery and embraced the gradual abolition and free Black colonization schemes that Northern white moderates, and many Founders, had supported for decades. “Existing slaveholders would have enjoyed decades to adjust, psychologically and financially, to a new regime of ultimate freedom for all,” Amar writes. This is wishful thinking. It ignores not only the fact that most free Black Americans had rejected colonization and gradualism, but also how profitable slavery had become. Southern cotton planters, along with sugar-producing slaveholders in Cuba and Brazil, weren’t marginalized by the emerging world of nineteenth-century industrial-capitalism—they became central to it. The beating heart of the Industrial Revolution—Britain—received 77 percent of its cotton from U.S. slaveholders on the eve of the Civil War, and, as Matthew Karp has argued, Southern secessionists were neither bluffing nor wrong to think that slavery’s future looked bright.

Perhaps the most damning critique is the one hiding in plain sight: the fact that Lincoln’s supposed originalism led to a civil war. If following the Constitution as the Founders originally intended required a war to end slavery, surely the Founders would have preferred making a few amendments to end the institution beforehand. In any event, the Founders themselves never believed the Constitution had a fixed meaning, as Jonathan Gienapp has recently argued in his book Against Constitutional Originalism: A Historical Critique.

Indeed, the fact that Lincoln and his successors had to amend the Constitution in order to build a more perfect union carries the opposite lesson Amar wants to impart. The Framers could have abolished slavery at the Constitutional Convention, but, for the price of union, they chose not to. The chickens eventually came home to roost. Under the Framers’ Constitution, slavery was allowed to continue, and states could restrict citizenship and bar people from voting. Regardless of whether it was what the Founders wanted, it was legal under the Constitution they wrote.

It wasn’t originalism that saved the nation or its Constitution, it was a decades-long struggle of ordinary people who knew what no document needed to tell them: They were all born free and equal. Sometimes their efforts were in accordance with the law, but sometimes they were in open defiance. Every time an enslaved person escaped to the North, and every time an abolitionist harbored them, they were flagrantly violating the Constitution. The lesson here can’t be that they should have been more faithful to the Constitution, good originalists like Lincoln. It’s that we should recognize the Constitution’s flaws, think creatively how we interpret it, and make it easier to amend. After all, no one wants another civil war.