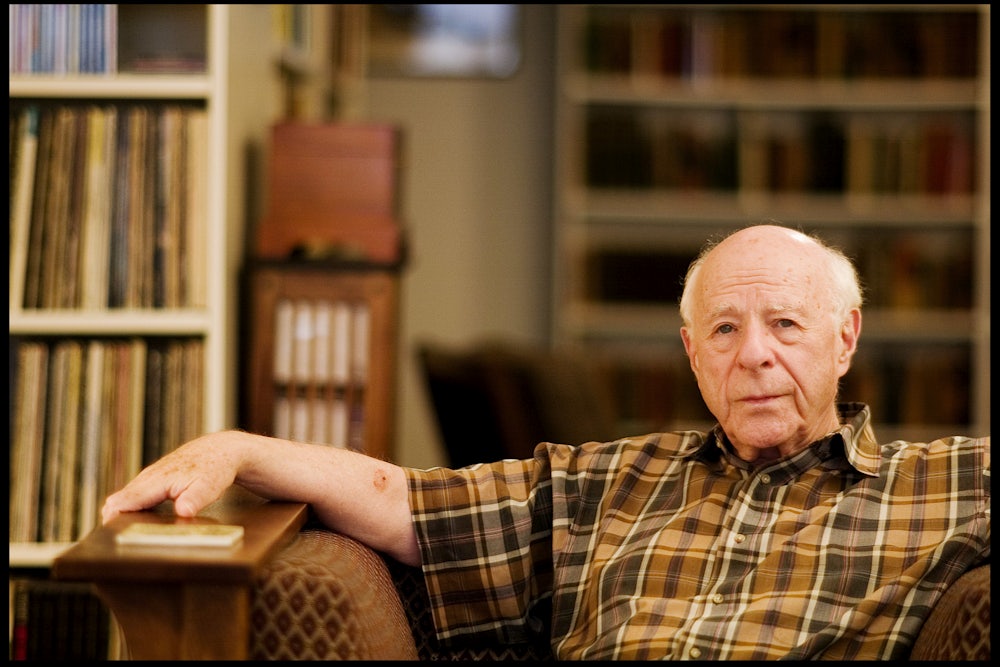

My late father knew Norman Podhoretz (Alav Hashalom) when they were both counselors at a Jewish summer camp in upstate New York. This would have been in 1946, maybe 1947. Assigned to write lyrics for an official camp song, they got in trouble for making satirical reference to the management’s pompous boast that it served “a cultured clientele.” I never knew the man (my dad was three years older, and they didn’t stay in touch), but I kind of like Podhoretz for that. It was a rare departure from his defining characteristic—a lifelong slavish adherence to a succession of orthodoxies.

Podhoretz was a quick study who believed the secret to success as an intellectual was to master some highly disciplined mode of thought and never deviate from it. Because this approach is obviously very confining, any thinkers and writers of any worth who start down this path break free of it. Podhoretz’s approach was different; when one orthodoxy no longer suited his purposes, he exchanged it for another, and then another.

Podhoretz eventually settled into neoconservatism, an intellectual movement that began as a liberal critique of the New Left counterculture, hardened into anti-liberalism, then degenerated into an indiscriminate military interventionism. You don’t hear much about neoconservatism these days because the Iraq War discredited it, starting around 2005. (Though Donald Trump’s latest folly, a potential regime change war in Venezuela, threatens a revival.) Podhoretz was perhaps neoconservatism’s last surviving active practitioner, and certainly the last survivor of an earlier milieu of Upper West Side liberal intellectuals known as “the family,” from which Podhoretz exited noisily with the 1967 publication of his memoir, Making It.

Making It is a better book than is remembered, mostly for the way it captures Podhoretz’s youthful resistance to assimilation into the goyische ruling class. His tutor in these matters was a high school English teacher he calls Mrs. K., who mentored him between the ages of 13 and 16. “My grades were very high and would obviously remain so,” Podhoretz writes, “but what would they avail me if I continued to go about looking and sounding like a ‘filthy little slum child’ (the epithet she would invariably hurl at me whenever we had an argument about ‘manners’)?” Podhoretz carried this identitarian resistance into Columbia, which sought to make of him “a facsimile WASP,” and what he writes about that is thrilling. But Podhoretz also came to regard academic achievement as a kind of cynical game, and what he writes about that is just depressing.

Podhoretz’s cynicism comes across most fully when he relates how, in graduate school, he shifted his intellectual loyalty from his mentor Lionel Trilling at Columbia (of whom Podhoretz had been “capable of an effortless imitation of the master’s style”) to F.R. Leavis, who taught Podhoretz on a fellowship in England:

I listened to him, I watched him, I studied his books. I appropriated his opinions and made them mine.… Before the end of my first year at Cambridge, the master’s ultimate accolade was bestowed upon me: he invited me to write for [the scholarly journal Leavis edited,] Scrutiny.

What Podhoretz describes here goes well past the influence of a great teacher on a bright student. By his own testimony, Podhoretz engaged in systematic and fully conscious mimicry, a sort of ChatGPT before its time. Podhoretz believed that in Making It he was telling an ugly truth about how everybody gets ahead in life. In fact, the book’s brutal reviews said, he was telling an ugly truth about himself. Wilfrid Sheed compared Making It to a seedy striptease:

Norman likes money (tiny bump), Norman likes to be well-regarded (desultory twirl of tassel). Sorry men, no refunds. It’s only on the way home that we realize that we have seen a rather dirtier show than we thought.

Podhoretz’s eventual response to such vilification was to abandon literary criticism altogether for political commentary; to convert to neoconservatism; and to bring Commentary, the magazine published by the American Jewish Committee that he edited for 35 years, along with him.

In 1976, Podhoretz co-founded the Committee on the Present Danger to oppose détente policies with the Soviet Union initiated by President Richard Nixon. In 1980, Podhoretz argued that the United States was surrendering to Soviet military superiority, when in fact the Soviet military was falling apart; within a decade it would lose Afghanistan to mujahideen, and not long after the country itself would cease to exist. What at first sounded like liberal apostacy quickly matured into alignment with the hard right. By the end of the 1970s, he was a Reagan Republican.

New information made little impression on him. Podhoretz responded to the 1993 Oslo peace agreement by writing that Israel was “becoming less sensible and less pragmatic.” In 2007, Podhoretz published a book titled World War IV: The Long Struggle Against Islamofascism, even as an American troop surge was turning the tide in a long Iraq War most Americans wished they’d never started. In 2022, Podhoretz said, “I am perfectly prepared to believe the 2020 election may have been stolen.” Never mind that his own son, John, who’d succeeded him as editor of Commentary, called 2020 “a staggering repudiation of Donald Trump.” When Podhoretz père subscribed to an orthodoxy, he didn’t make adjustments.

“The Neocons Were Right,” writes David Brooks in the December issue of The Atlantic. If you add to the end of that headline the words “About Trump,” I’ll agree; apart from Norman Podhoretz, it’s been hard to find anybody previously affiliated with neoconservatism who can stomach Trump. Brooks’s essay praises not late-stage warmongering neoconservatism but an earlier phase when it embraced moral agency and asked tough questions about failing liberal domestic policies like deinstitutionalizing the mentally ill. Even then, though, neocons were short on answers and deferred to the paleoconservative anti-government solution: Shut it down.

The only affirmative neoconservative policy I can name is to wage war. In Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush, the neocons found presidents willing to do their bidding, bankrolling an illegal war in Nicaragua in the 1980s and waging a pointless war in Iraq in the aughts. Both presidents turned away from the neocons in their second terms. Still, Norman Podhoretz’s ardor for the cause never flagged. He’d found his team, and he didn’t know any other way to play.