In June, as I was reading Tareq Baconi’s memoir Fire in Every Direction, Israel launched a series of surprise attacks on Iran. Though I was born in the United States, I have people in Iran, as well as a good many memories. For 12 days, I watched footage of fighter jets and exploding drones over and inside the narrow streets of Tehran, trading updates with family here as we texted and called with family there, until lines went silent due to outages. We were left with prayer, any agnosticism abandoned for hope.

This experience is unexceptional. In his memoir, Baconi writes of his own experience of watching turmoil from afar during the Second Intifada, as a college student in London. Against the reel of quotidian life in the safety of a Western country, this historic event gets relegated to a backdrop. “The Second Intifada was raging in the background, peppering conversations here and there, appearing in headlines on the evening news throughout my university years,” he recalls. “I felt vaguely implicated and entertained inane conversations with friends. But this was nothing more than passing commentary.” Baconi was born in the Palestinian diaspora, the second generation in his family to have been so. He traces his “trained” “silence” back to his parents and their friends, a generation of Palestinians who couldn’t afford to champion the struggle for independence while living in “host” countries like Lebanon and Jordan. (Indeed, the term “host” itself indicates their disempowerment; guests can always be kicked out.)

But going on to describe the tedium of his studies as an engineering major, Baconi divulges a more existential unease: “I shifted my gaze from the region, immersing myself instead in the study of thermodynamics, fluid mechanics, mathematics. I mapped fluid movement in pipes, wrote out eloquent integration sequences, grounded myself by designing intricate power plants.” As Baconi drifts from one activity to the next, his “I” hardly seems “grounded.” The cadence of these lines instead captures the alienation of witnessing the death of one’s people and destruction of one’s homeland from afar.

In the long run, however, Baconi did not avert his gaze: He pivoted from engineering to international relations in his mid-twenties, focusing on the region’s geopolitics, and going on to fellowships with the European Council on Foreign Relations and Al-Shabaka: The Palestinian Policy Network, where he currently serves as board president. Since Hamas attacked Israel on October 7, 2023, Baconi has been repeatedly called on to explain Hamas to the West. His 2018 academic monograph, Hamas Contained: The Rise and Pacification of Palestinian Resistance, which traces the group’s evolution over 30 years and draws on interviews with its leadership, became a go-to primer after the start of the war (alongside histories such as Rashid Khalidi’s The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine). Baconi was interviewed by Isaac Chotiner at The New Yorker and Ezra Klein at The New York Times, and has written about Palestine regularly for The New York Review of Books. In a new author’s statement prefacing his book, he writes of the paradox that “the vast destruction of the Gaza Strip and the horrifying loss of civilian life are a painful blow to Palestinians,” and that yet “simultaneously, Palestine is back on the top of the global agenda—with growing recognition that it must be addressed.”

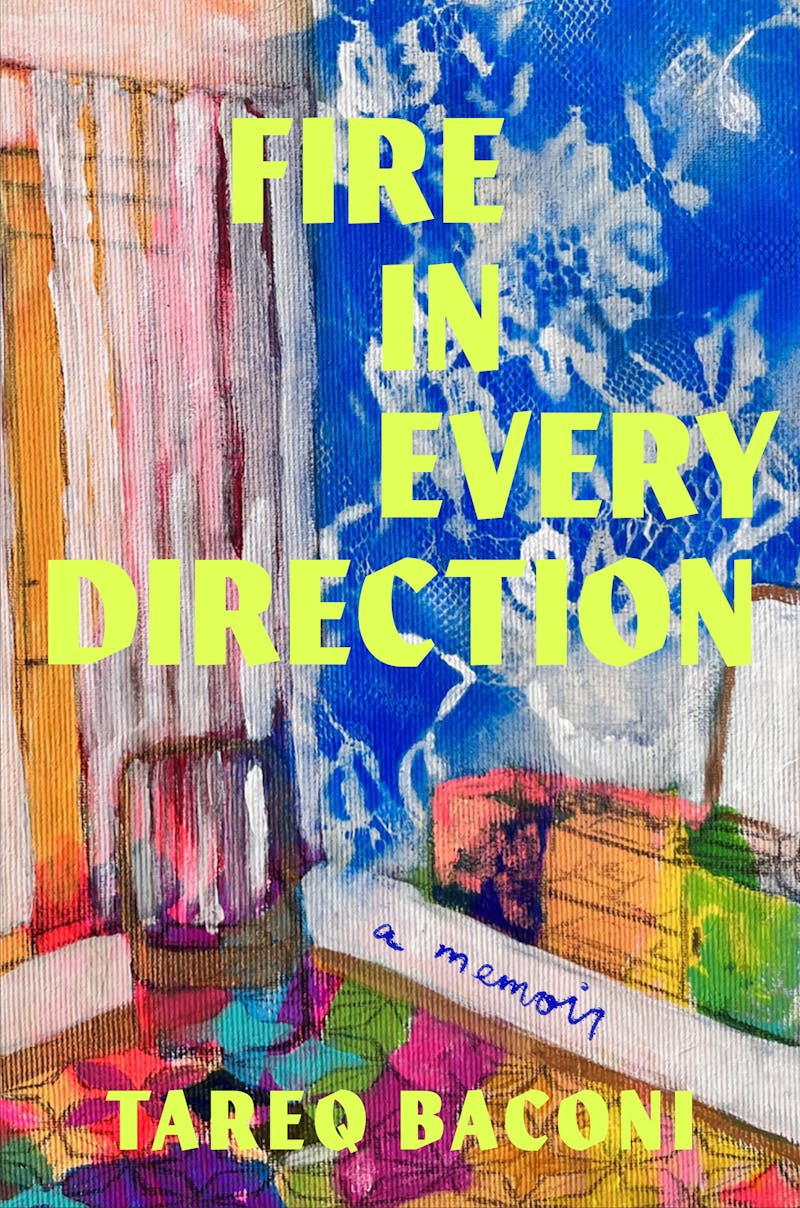

As a political analyst, Baconi has been tasked with explaining a brutal war; in his new memoir, Fire in Every Direction, he attempts the more modest project of accounting for an individual life, teasing apart the complexities of growing up gay and Palestinian, and putting forth those stories in all their knotted joy and melancholia, rage and confusion. He writes of a life haunted by ghosts: by the loss of his homeland and the specter of freedom, but also by the masking of his sexuality and the promise of wholeness.

The ghost whose presence is most strongly felt in these pages is that of Ramzi, Baconi’s best friend and crush from his adolescence in Amman. Letters from Ramzi are the soil from which the memoir grows; charmingly, these two teenage boys kept a correspondence fit for a Victorian novel. Baconi kept only his beloved’s letters and none of his own, he explains in the prologue, making Ramzi’s letters “an archived monologue, waiting to be excavated.” The memoir itself begs to be read as this lost half of the conversation, reinterpreted with the benefit of adulthood and analytic training.

For Baconi, there is a “before Ramzi,” and an after. “Memories crowd my mind when I conjure that world,” Baconi writes of the house in Amman’s Al-Abdali neighborhood where he spent his first 10 years, “before Ramzi and I met.” In the memoir, that “before” is relatively brief. Ramzi’s entrance in the story ushers in the pains of adolescence and of growing up queer. The boys become friends after Baconi’s family relocates to the posher, less central West Amman. Both families are Christian, a minority in Jordan, and send their boys to the National Orthodox School. But friendship does not come naturally. On the playground, Ramzi stands by as a young Tareq is taunted for what other children took to be his nascent gayness. (A classroom bully calls him “little girl.”) But when their mothers reunite the sons outside of school, the boys connect. Over the years, friendship turns into a crush, and as the boys’ capacity for feeling grows deeper and sharper, that innocent crush turns into a tortured love.

“My skin tingles writing this,” Baconi writes of a sexually tense moment in their late teens, “knowing that we were more naïve than brave.” He is on his knees, inspecting Ramzi’s “love trail” with the excuse of deciphering “a message for the prostitute” that Ramzi has shaved into his pubes. (Ramzi is headed out of town for a boys’ trip promising straight debauchery.) “Baba was less than ten meters away. Anyone could have walked in …” Yet in the moment of passion, “None of that mattered.” Before the thrill of this anticipated touch can be realized—“arm in midair, before my finger settled onto his skin”—the boys see themselves from the outside. This moment of recognition stretches time. “In a second, I saw how compromised I was. I looked up and our eyes locked. His smirk was gone, his mouth hung slightly open. His dimples had disappeared.”

Baconi and Ramzi have no choice but to acknowledge the tension between them. For Ramzi, that admission sours his image of his friend—and his image of himself. “His eyes bore into mine in a way I had never seen before. They were foreign, stripped of their warmth, seeing me anew, there kneeling in front of him. Lust mixed with disgust, power. Clarity.” By the time Baconi makes a formal confession of love—in a letter, of course—all has already been said.

The confession explodes young Baconi’s life. Spurned by his beloved, he is also rejected by Ramzi’s family, which has come to seem like an extension of his own. Telling his father of his feelings for Ramzi, he is not taken seriously, his attractions dismissed as the “normal” sexual confusions of boyhood. His mother takes him to a therapist who exudes a similarly gentle form of homophobia. Eventually, Baconi decides to leave the country. Instead of attending his parents’ alma mater, the American University of Beirut, he will go to London.

Before describing his last night in Amman, Baconi offers a reflection on exile, tracing his family’s movements since his grandmother’s home in Haifa was seized during the Nakba, in 1948. Zooming out, Baconi situates this personal inheritance within the twentieth- and twenty-first-century history of the region. “Every generation in my family fled their homes. Every generation in Ramzi’s did, too. Our grandparents, our parents; they fled war, death, gunfire. That is our fate, as Arabs, to flee. Is it not?”

And yet Baconi does not allow himself the pat comparison of likening his move to London—that is, his escape after coming out and realizing that he will not be able to become who he wants to be, should he stay—to forced migration. Mapping the twists and turns of his self-analysis, he writes: “It is easy for me to claim flight as my rite of passage, a completion of our lineage, joining millions of others in making homes for themselves in strange lands. But Ramzi’s eyes rest on me as I type these words, his admonishment burns into my back, calling on me to confront the hypocrisies, the lies we tell ourselves.” With time, the memory of Ramzi has grown into a fact-checker who refuses to let Baconi wallow in self-pity. Ramzi is “correct,” Baconi reflects: “What right do I have to speak of flight? I have survived no wars. My scars are invisible, my movement privileged.” Once a source of rejection, Ramzi now functions as the measure of Baconi’s analytic rigor, as the faculties he uses to make sense of the world in his political writing and scholarship are aimed at himself in this book. Baconi finally settles on the word “estrangement” to describe the alienation he was experiencing as a teen.

It is the journey of gradual estrangement, of alienation, that I am trying to convey. The feeling of not belonging that came to permeate my days. The conviction that one must remain hidden to live. Masked, covered. The inner bifurcation, the double consciousness. The exile of the authentic self.

Though many might read this young gay’s man leaving for London as an act of self-preservation, Baconi likens his pursuit of personal liberty and independence to addiction: “What I am thinking of is closer to the flight from reality that members of addiction groups invoke: the compulsion to exit one’s truth by creating an alternate one. The succumbing to the allure of a new beginning that becomes irresistible, almost existential, with time, making escape inevitable.” The metaphor is a strange one: It could be read as belittling his own experience; or perhaps, alternatively, as putting his experience into perspective, refusing to allow his individual pain to upstage his people’s. It also captures the urgency of the need to get away.

Despite pulling away from the comparison between his family’s exile from their homeland and his own estrangement from his sexuality, Baconi circles back to this comparison, coming to see both in terms of the human quest for “a dignified life.” “That is my individual flight,” he goes on, “my walking away from that deathly disquiet that was sucking the life out of me. Not exile, then, but estrangement into a world that I hoped would provide a dignified life, one worth living.” His is a story of self-determination, as an individual and a people. The two are inextricably intertwined in the memoir, a radical move in the context of a war in which LGBTQ rights are often used as a cudgel to vilify Palestinian culture.

In Amman, Baconi was troubled by the anti-Muslim rhetoric that plagued his Christian community. In London, he confronts blatant Orientalism from his peers. Continuing to struggle with his sexuality, Baconi sleeps with a string of women while courting an intimate friendship with a gay man who calls him “Arabia.” The nickname stresses that being accepted as a gay man will not shield Baconi from othering: To secure “a dignified life,” he will have to fight against racism and internalized homophobia.

Intimacy with another Arab diasporic man is what finally frees Baconi from his self-hate, both as an Arab and as a gay man. Studying abroad in Sydney late in college, he forms a deep, multifaceted relationship with Sam, who is Syrian Australian, and who, when he was younger, traveled all over the world for his parents’ work. Baconi confides in him his history with Ramzi as well as his antipathy for the concepts of shame and honor that helped structure his childhood. Within this intimacy, Baconi can break free of his past: “I spoke of bullying, and he defanged a million past insults. I told him of shame, and 3eib, and honor, and in his wondrous capacity to reshape things, he turned them around. No longer were they sources of guilt or judgment, but signs of community, of love and protection, tradition and meaning.” Seemingly for the first time, Baconi’s connection with another man is consummated, at once cerebral and sexual. “In return for my insight,” Baconi writes of Sam, “he gave me freedom.” It is the freedom of being whole. Of not censoring parts of himself for the sake of someone else, whether mind or body.

Only when Baconi discovers his calling as a thinker and writer does he truly come of age; in this story, coming out is not sufficient. A few years later, he goes back to school—to Cambridge—for a master’s in international relations, seeking to understand the region’s history as he has come to understand his own. There he meets the mentor who changes his life, “the person who has become the vehicle for all the conversations I do not yet know how to have in Amman.” Though he goes unnamed in the memoir, the scholar is the late George Joffé, a political scientist who regularly lectured at venues like the NATO Defense College, the Geneva Center for Security Policy, and the Royal College of Defence Studies in London.

Staying on at Cambridge for his doctorate, Baconi treats consulting as a day job, flying weekly between London and Dubai or Doha or Riyadh for work. (Eventually, he will abandon this more lucrative career altogether, breaking from prescribed masculinity in more ways than one, letting go of the money and status he has earned through the corporate grind to pursue a truer vocation.) When Baconi comes out to his father for the second time, his father makes a more sweeping argument about Arab homophobia, projecting his own latent sentiment onto Jordanian society. “People will not accept this here. We’re backward. We’re not like you or your friends in Cambridge. This is a different world. You cannot live here anymore.” And yet Baconi is by then regularly traveling to the region for work and will later move to Palestine, eventually making a life of straddling London and the Middle East. His life is a rebuttal of his father’s error.

Reading Baconi’s scholarship alongside the memoir suggests a more productive estrangement: As a scholar, he questions the central institutions and assumptions of his field. In Hamas Contained, Baconi describes how international law refuses to legitimize the Palestinian struggle for independence while failing to hold Israel accountable for war crimes and other atrocities. Much of his discussion revolves around the debated definition of terrorism and the inconsistent application of the term. Which is to say, the word terrorism has itself been weaponized. “Classifying Hamas as a terrorist organization has justified sweeping military action against Palestinians, depoliticizing and dehumanizing their struggle,” Baconi writes in his preface. “It has also prevented the possibility of viewing Palestinian armed resistance as a form of self-defense within the context of war.” Our definitions of war are outdated, he maintains: “How are civilians defined in a world where the notions of war and peace are increasingly difficult to ascertain, and where the form of warfare has outgrown the very laws that define it?”

In the memoir, Baconi sheds his scholarly remove. Living in Ramallah with a British passport, he writes about Gaza:

Israeli soldiers hiding behind sand dunes—cowardly and camouflaged and decked out with the deadliest technology—snipe [Gazan residents] off, one at a time, for no reason other than that they can, frightened by a Palestinian asserting their presence. And supposedly civilized nations hail Israel’s accomplishments, moronically parroting Zionist rhetoric, pretending that Israel is facing hordes of terrorists. A catchall descriptor that erases our history and justifies all forms of evil to be unleashed against us. For that is all we are in their eyes. It is all we have ever been.

In many ways, Baconi’s contributions as a scholar have rested on his embracing the position of the outsider, his aptitude for reframing the conversation and calling into question its very terminology. Whereas his scholarship takes a measured tone, Baconi allows the memoir to drip with sarcasm and anger.

In love and work, the memoir’s arc is triumphant. As in most first loves, the pain that young Tareq experienced with Ramzi turns out to be temporary, and by the end of the book, middle-aged, Baconi is happily married to a man. Ramzi has come to represent all that Baconi has rejected personally and professionally: Baconi learns through the grapevine that his old friend lives and works in Dubai, and has a young family—a cookie-cutter life for a man of their upbringing. He fantasizes about coming out to Ramzi for the second time, considering reestablishing contact on a trip to Dubai: “I recount that I am married to a brilliant and adoring husband, we have a beautiful home in London, and we’re getting a dog.” Ever aware of his own privilege—and fearful of neatly fitting a Western liberal fantasy, even with the context of his literal fantasy—he adds: “A swift tumble of an update—one dripping with domesticity.” His own life, he is well aware, is merely someone else’s picture-perfect. His own, perhaps, but with one glaring hole: Liberated as Baconi is—personally and professionally, emotionally and intellectually—Palestinian liberation remains to be achieved.