On a cold Valentine’s Day in 2012, three women walked down a Beijing shopping street in white wedding dresses smeared with red to look like blood. (It was lipstick.) They had bruises on their faces, as if they’d been beaten. (It was dark-blue eye shadow.) They chanted, “Yes to love, no to violence.” Photos of the protest spread instantly across the Chinese microblogging platform Weibo.

The “bloody brides” were the invention of Lü Pin, founder of Feminist Voices, a digital magazine that had grown into a viral Weibo hub for young women unwilling to stay quiet. Activists called 2012 “Year One of the Chinese feminist movement.” Women shaved their heads to protest higher-education quotas that favored men, rode the subway with placards denouncing gropers, and Li Maizi’s “Occupy the Men’s Bathroom,” demanding more women’s stalls, trended on Weibo.

These actions produced real legal and policy shifts. The Ministry of Education discontinued discriminatory college quotas, and a Beijing court for the first time issued a domestic violence protection order, ruling in favor of a U.S. citizen who sued her Chinese husband, a millionaire celebrity English teacher. China passed its first national anti–domestic violence law, and new buildings were required to add more women’s bathrooms.

What made this surge of activism possible was Weibo. Launched in 2009, it quickly became the nervous system of China’s civic sphere. Before Weibo, feminist organizers could hand out newsletters or hold a small meeting but never get on state TV; afterward, they could turn a street protest into a nationwide conversation. A clever slogan or striking image could trend for weeks.

Weibo marked the moment when young Chinese women discovered that even the most heavily restricted internet in the world contained a crack large enough to push a movement through. In May 2009, a spa worker was cornered by two local cadres demanding “special services.” One slapped her with a wad of cash and shoved her onto a sofa, where she stabbed him in the neck, killing him. Police detained her on suspicion of murder, but the case exploded on social media, and prosecutors had to drop the murder charge, conceding she had acted in self-defense. In October 2010, a drunk driver who had killed a student tried to flee from the police as he shouted, “My father is Li Gang!”—a local security official. The phrase went viral at the start of what came to be known as the “Weibo Spring,” when “Big V” accounts—bloggers with a large following who were “verified”—turned scandals like these into national dramas.

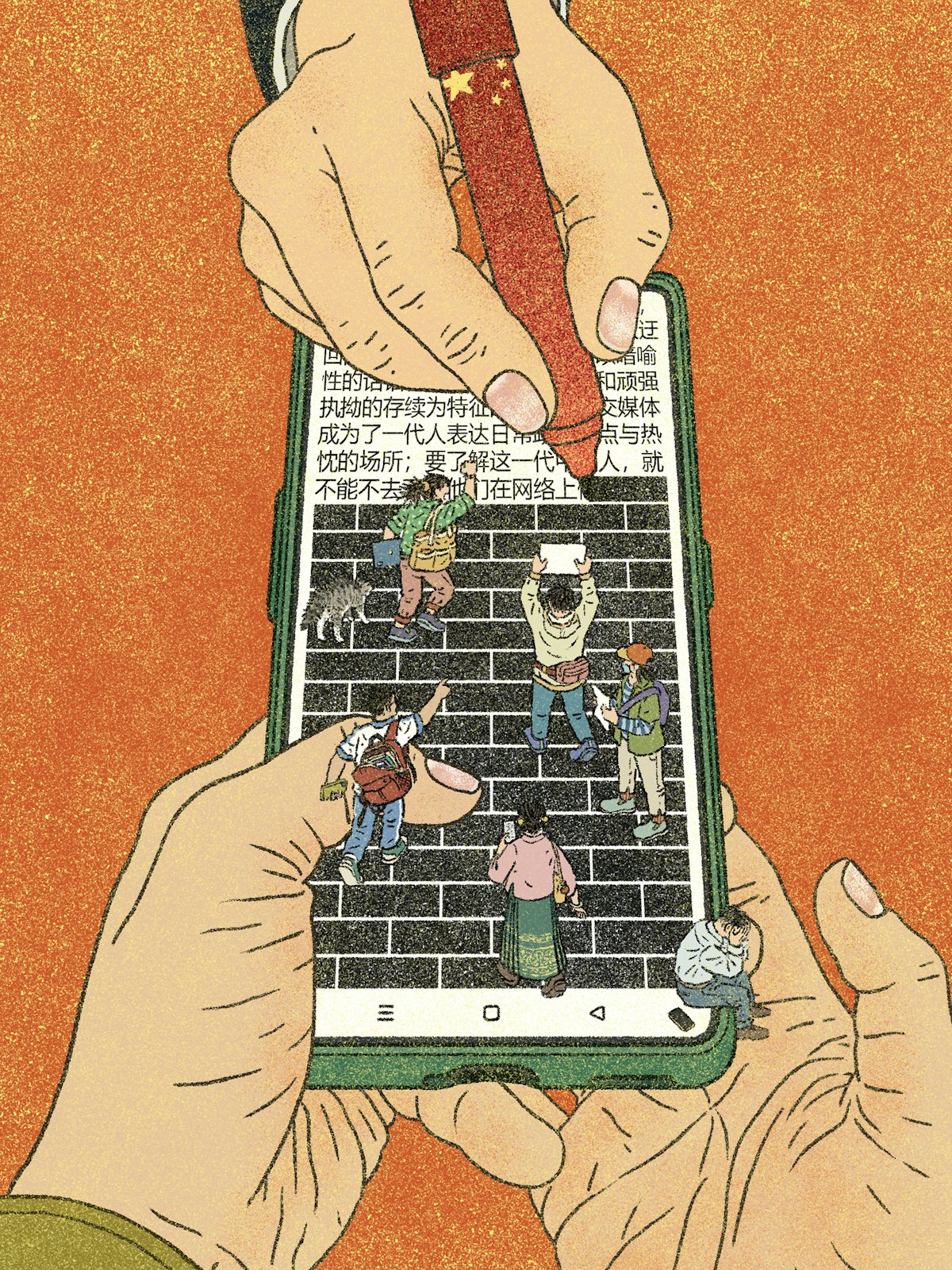

This rise of the mobile web in China in the 2010s produced a flowering of digital creativity even as suppression intensified—a tension at the heart of Yi-Ling Liu’s eye-opening book The Wall Dancers: Searching for Freedom and Connection on the Chinese Internet. Writing as someone who grew up alongside this digital universe, Liu reveals how censorship does not simply extinguish voices, but reshapes them—training a generation to speak sideways, turning repression into a culture of coded speech, creative improvisation, and stubborn survival.

It might be hard to build a book around online life, but Liu—who grew up in Hong Kong, lived in Beijing, and even interned at the state-run China Daily (as I once did) before writing for The New Yorker and The New York Times Magazine—follows a group of effervescent netizens (Lü Pin, Li Maizi, and others, including herself) who more than carry it. Take the episode of Li’s “Occupy the Men’s Bathroom” protest: The day after, two police officers picked her up. But to her astonishment, they didn’t arrest her. Instead, they treated her to a feast at a fancy restaurant, though they did tell her to stop protesting and posting on Weibo. The incident perfectly captures the odd, shifting political culture of the era, and in tracing such encounters Liu shows how social media became the space for her generation to work out the politics and passions of their everyday lives. To understand the Chinese people, understand what they’re doing online, she proposes. What emerges is a portrait of nonconformists who, by feeling out the walls the regime has built, turn that maneuvering into a kind of limited freedom. They do not escape the system; they improvise within it. They dance.

Western observers have long swung between two caricatures of China—booming economic miracle or iron police state—and then demanded to know which is “real.” Cultural historian Ian Buruma tried to look past that binary. In his 2001 book, Bad Elements: Chinese Rebels From Los Angeles to Beijing, he traveled through the Chinese-speaking world to portray a scattered cohort of mavericks pushed to the margins yet still feeling out the system’s blurred edges: disillusioned activists, political prisoners-turned-businesspeople, human rights lawyers, Christian sect leaders and followers, and online critics. By tracing this unruly mix, Buruma punctured the myths of Chinese sameness and pointed to a messy underground current.

An early online dissenter was Liu Xiaobo, who had been released from a labor camp two years earlier, in 1999. He recognized quickly how the emerging internet could allow everyday people to reach one another without passing through official channels. Cases that once were ignored—corruption scandals, police abuses, violence against women—could suddenly circulate everywhere. Liu, who would win the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010, encouraged this new civic scrutiny, supporting figures such as Dr. Jiang Yanyong, whose revelations about the true scale of the 2003 SARS outbreak ignited a fury. Commentators began calling 2003 “the year of online public opinion.”

From the state’s perspective, this was dangerous in a new way. One of the party’s governing tools has long been what sinologist Perry Link calls “fossilized fear”: Citizens self-police even before an officer appears. They say one thing in the open and another in private; topics such as Tibet, Taiwan, and Tiananmen—the “three Ts”—are off-limits. In 1998, the Ministry of Public Security launched what it called the Golden Shield Project—an effort to create an integrated surveillance-and-filtering system that would let the authorities watch, sort, and erase content, and block and arrest violators. Outside China, it became better known as the Great Firewall of China, the title of a Wired article. As Jack Goldsmith and Tim Wu note in Who Controls the Internet?, the wall was built partly with “American bricks,” with key technology from Cisco and other firms.

By the end of “the year of online public opinion,” the Great Firewall had gone live. Detentions for offenses rose; overseas websites were blocked; filters swept pages for banned words. But the result was what former CNN Beijing bureau chief Rebecca MacKinnon, in her 2012 book, Consent of the Networked: The Worldwide Struggle for Internet Freedom, dubbed “networked authoritarianism,” in which tightly managed digital spaces still generate unpredictable discourse. MacKinnon argued that, even under authoritarian rule, social media inadvertently broaden the space for public conversation, creating rolling negotiations between state and society.

The wall dancers emerged in that space, devising ingenious ways to slip past filters and tunnel under the Great Firewall. It wasn’t only activists and writers who sidestepped, but millions of ordinary participants who wanted to say what could not be said. To express “fuck your mother,” they recast the Chinese words caonima into a homophone that translates as “grass-mud-horse” and turned it into an alpaca meme. Another phrase, hexie, or “harmonization,” a euphemism for censorship, became “river crab.” The two animals were often portrayed in mortal combat, showing just how web-savvy individuals felt whenever posts vanished or comments were scrubbed.

Then there was Ma Baoli, a married, then-closeted police officer in a northern port city who built a networked bulletin board for gay men. His hobby became Blued, one of the world’s largest queer social platforms and, eventually, a key hub for HIV-prevention campaigns and public health outreach. To survive, Ma learned to speak in the language of public service and medical necessity, partnering with state agencies while offering users a measure of private freedom.

The good times would not last. In 2011, amid protests over illegal land grabs and Weibo chatter about a Chinese “Jasmine Revolution,” party leaders were terrified of social media’s ability to organize mass movements. Then-President Hu Jintao ordered significantly greater control of the internet and public opinion; within a year, Xi Jinping was elevated as his successor. Nicholas Kristof infamously predicted that Xi would be a reformer, and that Liu Xiaobo, who had been imprisoned in 2008 for a fourth time, would be freed.

Instead, one day the “Big V” writer Murong Xuecun found his social media accounts deleted. Months later, the outspoken billionaire investor Charles Xue was jailed for soliciting a prostitute, in what appeared to be a warning aimed at social media users. Xi created the Cyberspace Administration of China and installed Lu Wei, a zealous former propaganda official, as its first chief. The CAC drafted a cybersecurity law requiring that data on Chinese citizens gathered within China be kept on domestic servers and mandating that platforms edit content and monitor private chats. Unauthorized virtual private networks, or VPNs, hitherto used to bypass the Great Firewall, were criminalized, and several sellers were jailed; Apple removed hundreds of VPNs from its Chinese app store.

In 2013, someone began circulating side-by-side images comparing Xi walking with Barack Obama to Winnie the Pooh strolling with Tigger. It was lighthearted, maybe even meant affectionately. But the joke soon turned into mockery, used as visual shorthand whenever netizens wanted to criticize the increasingly despotic president. By 2015, Xi’s tolerance had evaporated. Pooh was axed from Weibo and WeChat. Searches were throttled. GIFs vanished. The China Netcasting Services Association issued guidelines banning content that “hurt the feelings of the Chinese people” and directing posters to promote “positive energy,” praise the motherland, and applaud its heroes and its rulers.

The state’s attitude toward culture shifted from wary tolerance to active engineering. Hip-hop was banned from state television. A single quip by a stand-up comic prompted regulators to accuse him of insulting the People’s Liberation Army and resulted in a multimillion-dollar fine for the company that booked him, casting a chill over the entire comedy scene. “Little Pink” nationalist commenters flooded the Facebook page of Taiwan’s President Tsai Ing-wen, harassed brands like Lancôme for working with the Hong Kong singer and activist Denise Ho, and heaped fury on Lady Gaga for meeting the Dalai Lama.

On March 6, 2015, while Lü Pin was away in New York, five other core members of the feminist movement, including Li Maizi, were detained and charged with “picking quarrels and provoking trouble.” That summer, in the “709” campaign of July 9, more than 300 human rights lawyers were interrogated or arrested on accusations of “subverting state power.” When China’s #MeToo movement began spreading under yet another animal homophone—mi tu sounds like “rice bunny”—Feminist Voices joined in, but soon the account was purged by Weibo and WeChat, erasing the country’s most influential feminist outlet from cyberspace.

By 2019, as Xi presided over the People’s Republic’s seventieth anniversary, official culture leaned hard into muscular nationalism, warning against the “feminization” of boys and exalting a virile ideal of Chinese manhood—a campaign that culminated in a formal ban on “sissy men” from screens. Ma Baoli’s dating app Blued—once hailed as a landmark of queer tech entrepreneurship and fresh off an $85 million NASDAQ listing in 2020—soon faced regulatory pressures and was forced to go private again as Xi’s regime cracked down on LGBTQ+ content.

In 2021, tennis star Peng Shuai posted on Weibo accusing former Vice Premier Zhang Gaoli of sexual assault. Monitors yanked the post within minutes and scrubbed her from searches. She was no longer seen in public, and her brief reappearances later were closely stage-managed. When a surveillance video of a brutal assault on women in a Tangshan barbecue restaurant in 2022 went viral, Weibo wiped the “rice bunny” phrase and removed thousands of posts, blocking accounts for “inciting gender conflict.”

The clampdown has reached every professional sphere. At universities, courses on “Xi Jinping Thought” and nationalist themes are now mandatory, while the state has increasing influence over hiring, research, and campus speech. Law firms must establish party cells that shape hiring and case selection, and many now avoid politically sensitive clients to reduce the risk of investigations or disbarment.

Corporations, too, were brought to heel. Even Jack Ma, founder of Alibaba, China’s dominant e-commerce giant, disappeared from view after criticizing regulators. Alibaba was fined $2.8 billion for having allegedly “eliminated and restricted competition in the online retail platform service market.” The planned stock market debut of Ant Group, Ma’s fintech firm, set to be the largest IPO in history, was abruptly halted. The result is a choreography of threats and capitulation, a pas de deux between state and citizen. The number of active websites in China shrank by roughly a third between 2017 and 2023, to about 3.9 million—fewer sites than exist in Italian and a fraction of the Japanese web, even though these languages have far fewer speakers.

Hong Kong offers a glimpse of what happens when that dance is imposed all at once on a previously free society. On June 30, 2020, Beijing’s national security law took effect in Hong Kong. Overnight, slogans once shouted on the streets became potential evidence of “secessionist intent.” Protesters were arrested and quickly silenced.

Media outlets such as Apple Daily and Stand News were raided, and their editors were convicted in the first sedition cases since the territory passed from Britain to China in 1997. Apple Daily’s former owner, 78-year-old Jimmy Lai, who has already been in prison since 2020, was recently found guilty on four national security charges, including colluding with foreign governments, and could face a life sentence. The public broadcaster RTHK, once compared to the BBC for its independence, was brought firmly under the government’s grip, and its television program Headliner, Hong Kong’s longest-running political satire show, was taken off the air after regulators ruled that an episode had “insulted” the police. Celebrities like Denise Ho were blacklisted—concerts canceled, endorsements withdrawn, and jobs evaporated.

College professors were detained or had contracts not renewed amid disciplinary procedures linked to political activity, and student unions were dismantled. Museums, nonprofits, and foundations have revised programming or leadership to stay within ideological bounds. As on the mainland, law firms avoid cases that might draw official scrutiny. Cathay Pacific was accused of “support” for the protests after staff expressed sympathy, prompting the Civil Aviation Administration of China to issue unprecedented directives threatening the airline’s access to mainland airspace. Top executives resigned, and employees suspected of supporting the protests were fired or disciplined. Every major Hong Kong company got the message: Stay silent or be punished.

For journalists like Allan Au, a meticulous columnist and lecturer in journalism at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, the new order arrived as a shock. Au had spent decades in Hong Kong’s media, at the TV network TVB, where I was his colleague, then as a popular host at RTHK, before being dismissed in 2021 as the government reined in the station. He continued to write sharp commentaries for outlets including Stand News, the kind of journalism that once felt safe in Hong Kong, on broadcasters’ eroding independence and how the creeping normalization of self-censorship was hollowing out the city’s press. In April 2022, national security police arrived at his home before dawn and arrested him for “conspiracy to publish seditious publications.” The message was unmistakable: Words that had once been part of ordinary argument were now criminal. Au was forced to take a leave from his teaching post and placed under restrictive bail conditions that effectively bar him from leaving Hong Kong; his passport was confiscated, and the sedition charge hangs over him like a suspended sentence.

When the city’s deadliest fire in decades broke out in late November 2025, killing at least 160 people, public anger raged across the internet. But authorities have used the national security law to expand their crackdown, arresting those who called for government accountability. Since the imposition of the national security law, at least 279 people, many of them activists, journalists, and academics, have been arrested; 149 were formally charged, 109 were found guilty, with 34 more overseas activists targeted with arrest warrants and bounties.

If Hong Kong shows how a free city can be compelled to learn the dance, the United States now faces a no less unsettling question: whether its own walls are starting to rise—not through outright deletions, but through political arrests and prosecutions, institutional capitulation, regulatory threats, and corporate submission.

The American version is not wholesale erasure but an escalating speech war, where the consequences increasingly include defunding, firing, prosecution, and even deportation. In the latest Trump administration, an executive order grandly titled “Restoring Freedom of Speech and Ending Federal Censorship” has coincided with investigations, license threats, and funding cuts aimed squarely at the president’s critics. Protesters have been charged under federal statutes; ICE has targeted noncitizens involved in pro-Palestinian demonstrations for detention and removal.

Newsrooms face mounting political pressure as Congress and the White House have terminated almost all federal funding for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and private media conglomerates like Paramount (CBS), Disney (ABC), and Warner Bros. Discovery (CNN) have sidelined or dumped outspoken voices while their owners attempt to stay in the administration’s good graces amid renewed antitrust scrutiny and pending mergers. David Ellison’s acquisition of Paramount was approved by the Trump administration only after Paramount paid the president $16 million to settle his lawsuit against 60 Minutes, and now Ellison is hoping for Trump’s blessing in his bid to outmaneuver Netflix to buy Warner Bros. Discovery. In December, Ellison’s new hire as editor in chief of CBS News, Bari Weiss, abruptly pulled a 60 Minutes segment on the stories of Venezuelan migrants who have been deported by the Trump administration to a notorious prison in El Salvador.

Institutions from the Smithsonian to major foundations have been faced with political warnings, audits, and leadership shake-ups. Universities have become battlegrounds: presidents dragged before Congress, student protesters expelled or arrested, faculty disciplined for dissent, and billions of research funding frozen. Jimmy Kimmel, of course, was suspended by ABC and pulled by Nexstar Media Group and Sinclair Broadcast Group, after a joke that offended the president and FCC Chairman Brendan Carr.

Trump carried out an unprecedented assault on major U.S. law firms that had opposed him, issuing executive orders and presidential memorandums that restricted lawyers’ access to federal buildings, barred them from government employment, canceled contracts, and threatened companies that hired them—pressure that pushed firms like Paul Weiss to make deals and pledge nearly $1 billion in pro bono work. Meta, Target, Amazon, McDonald’s, Walmart, and many others have eliminated or rolled back their DEI programs under Trump’s coercion. Each is choosing compliance over becoming the next cautionary tale.

Does this sound familiar? What begins as bare-knuckled politics ends as outright silencing. It is no longer culture war—it is delegated repression and state persecution. The First Amendment still offers a legal shield, and the United States lacks a centralized Great Firewall. Yet the pattern of control is unmistakable. The tools differ from China’s; the methods rhyme. We are not living behind China’s wall, but America’s own dance of censorship has already begun.