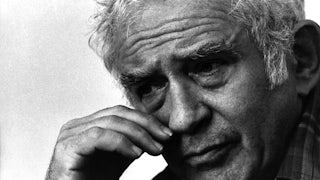

Denis Johnson wrote about some of the most unlikable characters in American fiction, and yet he always managed to make readers care what happened to them. This talent may have had something to do with many unlikable qualities in Johnson himself that, through the force of his dedicated and uncompromising talent, carried him through three marriages, nearly two dozen books of poetry and fiction, several plays and screenplays, and numerous darkly recurring periods of addiction. It would be fair to say that, throughout his adult life, he was either suffering from addictive disorders or engaged in 12-step programs to keep them at bay.

Johnson’s major and minor characters were doped-out criminals, doped-out derelict parents, doped-out journalists, and a frenetic range of doped-out CIA agents, drug smugglers, motorcycle gangs, hit men, and American Special Forces ops. In his best-known and most successful book—the small but powerful series of character-linked short stories Jesus’s Son—they were simply doped-out dopers, often stealing the money they needed to buy drugs, living in communal packs in order to save money to buy drugs, and taking ugly late-night jobs—such as cleaning blood off a hospital floor in the most memorable of these stories, “Emergency”—in order to, you know. As one recovering narrator recalls in The Largesse of the Sea Maiden: Stories, Johnson’s excellent last book of fiction:

Just to sketch out the last four years—broke, lost, detox, homeless in Texas, shot in the ribs by a thirty-eight, mooching off the charity of Dad in Ukiah, detox again, run over (I think, I’m pretty sure, I can’t remember) then shot again, and detox right now one more time again.

As the same character finally concludes, his gravestone will almost certainly read: “I Should Be Dead.” Which might actually be reassuring, since death is the only form of detox that Johnson’s most troubled characters aren’t doomed to repeat.

As Ted Geltner recounts in his enjoyable, narratively brisk, and compassionate new biography, Denis Johnson wrote about difficult (and sometimes even awful) people from the inside out. Born in Munich in 1949, and gifted with supportive, intelligent parents (his father was a career diplomat who worked with the FBI, CIA, and the U.S. Information Agency), Johnson spent his early years in the Philippines, Japan, and Washington D.C., during which time he developed many of the attributes of a creative personality: He learned to prefer reading books to taking classes about them, and he often got into trouble. Early in adolescence he was suspended for “disruptive behavior,” and later, at 14, he developed a predilection for rum. As he grew older, he developed a lot more predilections.

Geltner does for Johnson what Johnson did in his best fictions, offering us a deep, honest vision of a complicated, and often quite selfish, man while still bringing out what was most moving, generous, and poetic about him. In many ways, Geltner’s previous biography—of the wild, self-taught punk-country genius who wrote some of Southern gothic’s raunchiest novels, Harry Crews—was the perfect preparation for this one. In other ways, Johnson’s privileged childhood, his clean-cut and deceptive good looks, and his successful path from one prestigious literary grant or award to another, makes him Crews’s opposite. And yet both wrote books that were unlike the books of anybody else in their generation; and both lived hard-fought lives that left as many marks on Johnson’s soul as they did on Crews’s face and body.

What saved Johnson (and so many writers) from a life of pointless crime and sadness was his love for books. Determining as a teenager to write poetry, he went to the University of Iowa creative writing program when he was 18. Within months of enrolling, he was the writer to whom all the other students chose to compare themselves. He made fast friends with Raymond Carver and Robert Stone (two other notoriously addictive personalities) and visiting writers such as Charles Bukowski, who lived full-time on the darkest roads of poverty and alcoholism that Johnson managed to visit only for brief periods in between recoveries. And he quickly developed a knack for winning writing awards and grants—everything from small university summer grants to the Guggenheim, the Frost Place poet-in-residence, and the Lannan Fellowship.

Like Zola, he treated the world around him as his own personal laboratory experiment, and from a young age always seemed to be scrounging through the lives of his friends and acquaintances for material with which to fashion his stories and poems. “He cultivated friendships with the oddballs and intriguing characters who populated the bars, bookstores, and other gathering spots from one end of town to the other and beyond,” Geltner writes. “He would sit down and start conversations with people who he considered characters,” his first wife, Nancy Jo Lister, recalled. “He was always trying to harvest words or emotions or outlooks that he could then file away in his head. It was part of who he was when I first met him. Iowa City had its share of oddballs, and Denis knew them all.”

Eventually, the most dismal characters and raunchiest private adventures of Denis’s youthful indiscretions would come together in his cult novel/story cycle, Jesus’s Son; but his earliest success as a fiction writer began with a short story based on a conversation he overheard between a young woman and her daughter on a Greyhound bus late at night. “Move your foot,” the woman had said. “I’m tired now. Move your foot or I’m going to have the bus driver stop the bus and we’re going to put you off the bus in the dark and we’re going to drive away.” As the story develops, she gets drunk with a fellow passenger named Bill Houston, and the finished story, “There Comes After Here,” charts their intertwining errant paths into the Midwestern darkness. Eventually, after a few years’ hiatus, Johnson would return to the story, which became the opening chapter of his first novel, Angels (1983).

Also early in his time at Iowa, he married Lister, who was as young and unprepared for parenting as he was. And when she went into labor (at only 18 years old), Johnson was so drunk the nurse wouldn’t allow him into the delivery room. The couple named the child Morgan, after a popular 1960s British film comedy about a London artist who runs around London acting like a gorilla. It was an image with which Johnson and his wife seemed to connect.

Johnson was either unprepared for fatherhood or simply not very interested in the idea. He spent his free time getting drunk with friends, and made money by selling “nickel bags of marijuana in College Green Park.” He and his friends lived in a farmhouse where they began to accumulate guns, drugs, and booze; and tensions (as you might expect) grew to the point where one of them was shot. (Johnson managed to avoid being the victim of the many violent and sometimes deadly accidents that regularly occurred all around him—car crashes, guns going off, police raids, etc.) His early fiction and poems treat children as little distractions who are easily forgotten—as in the opening chapters of Angels, when the boozy young mom, Jamie, wanders through city streets with a strange man and seems to completely forget the baby and small child accompanying them. The poem “Talking Richard Wilson Blues, by Richard Clay Wilson” (published in his collection The Veil in 1987) depicts a toddler as the product of an intimate theft, in which a woman takes “that warmth between you” and

It changes into a baby. “Here’s to the

little shitter,

The little linoleum lizard.” Once he

peed on me

When I was changing him—that one got a

laugh …

Before his son was 2 years old, Johnson had checked himself into his first psychiatric clinic for addiction; shortly afterward he divorced Lister, and was soon living with another woman and a whole new set of predilections.

After three books of poetry published between the late ’60s and the early 1980s, Johnson wanted to try his hand at a book of fiction. In 1980, in order to research a novel, he began teaching a yearlong workshop at Arizona’s Florence State Prison, where he left few human stones unturned. At his first workshop, he singled out one young man as the best writer in the group—he turned out to be the multiple murderer Robert Benjamin Smith, who, at the age of 18, had entered a Mesa Arizona beauty parlor and shot four women and a 4-year old child in the head, execution-style. (Smith had spent the previous months “researching” the crimes of Charles Whitman, who had killed 15 and wounded 31 on the University of Texas, Austin campus.) Sentenced to death, Smith spent several years on death row, where he gathered up much of the firsthand experience that Johnson would later use in Angels, his story of crime and punishment in middle America, stretching from the Chicago rape of one character to an Arizona robbery and murder committed by another. The concluding chapter, in particular, draws from Smith’s material, when Bill Houston awaits his last meal, his walk to the gas chamber and, in Death Row parlance, that moment when he would be released from the misfortunes of his life by “going up the pipe.”

Johnson’s acceptance of poorly directed human passions and manias was never better expressed than in this first novel, with its sense of lost souls in a world that doesn’t understand them and doesn’t care to. During his murder trial, Bill Houston sees this alien world assemble around him, as he watches

his trial from behind a wall of magic, considering with amazement how pulling the trigger had been hardly different—only a jot of strength, a quarter second’s exertion—from not pulling the trigger. And yet it had unharnessed all of this, these men in their beautiful suits, their gold watches smoldering on their tan wrists, speaking with great seriousness sometimes, joking with one another sometimes, gently cradling their sheafs of paper covered with all the reasons for what was going on here.

Johnson’s criminal losers aren’t evil so much as they fail to see reasons to be good.

The novel earned many strong reviews, some prestigious foreign rights sales and film money, and landed Johnson on GQ’s list of “tomorrow’s literary lions.” With this small solid success at his back, he embarked on a series of “fiction finding” missions. On assignment for Esquire, he visited Costa Rica and Nicaragua; he journeyed to Mindanao in the Philippines to interview Muslim secessionists and to west Africa to cover the First Liberian Civil War. Closer to home, he mined his trips to Key West for his second novel, Fiskadoro (1985), set in a postnuclear seafront village named Twicetown (commemorating not one but two nuclear strikes), populated by a cultural motley of fishermen and leaderless military personnel staffing the bombed-out local bases. Johnson’s plots (especially this one) are sometimes less satisfying or even comprehensible than those of writers like Robert Stone, who influenced him, but he brings many passages to life even when it’s hard to distinguish why those passages are narratively significant.

More successful was his third novel, The Stars at Noon (1986), which traces the escape pattern of a drug-addicted part-time sex worker trying to find her way from Nicaragua back to the States without getting killed—all related in the desperate, poetically intense voice that recognizes the world’s horrors and beauties, even while she has trouble finding a way through it. And Johnson eventually put his African journeys to use in his last, Conradian novel, The Laughing Monsters (2014), about a former U.S. intelligence operative in West Africa who returns 10 years later in order to buy and sell whatever he can get his hands on—from government documents to uranium 235. Like Graham Greene or Robert Stone, Johnson never seemed to go on holidays or take “trips.” He roamed the world accumulating material.

Even as he established himself professionally, Johnson’s personal life remained tumultuous. In the early ’80s, when he moved with his second wife, the artist Lucinda Johnson, to the small Cape Cod seafront town of Wellfleet, Massachusetts, he was soon charging ahead with his increasingly common practice of committing serial infidelities, which were interspersed with intense periods of apology, reavowal, and unfulfilled promises to get himself back to AA. “I remember getting really tired of it,” Lucinda recalled. “You [confess], and you’re pardoned, it’s like, okay, are you just going to keep doing the same thing over and over? How many times can you say you’re sorry?”

Memories of his years of university, drugs, rehab, and more drugs again would prove his most enduring source of inspiration. After a journalistic adventure to the Philippines put him in hospital with malaria in 1988, he felt too broken to focus on a long project, and so he pulled some disjointed autobiographical pieces out of a drawer that had embarrassed him so much that he had never considered publishing them. They were episodic, offbeat, and often ended with ironic asides or afterthoughts that neither commented on the main events of the story nor resolved them. They were more like Zen-ish parables that took off from the story in the same ways that Johnson had taken off from so many urgent events in his life, and as he worked the stories into shape, he decided he didn’t have to be ashamed about his past anymore. “I think after going through the common humiliations of a human life,” he later said, “I realized it just doesn’t matter.… There’s nobody who can disguise himself.”

The stories not only helped him break into the front ranks of publishing at The New Yorker (at that time far from the sort of venue one would expect to feature stories about strung-out junkies, let alone ones in which the central character was referred to only as “Fuckhead”), but the finished book would become a surprise bestseller and a just-as-surprising small-budget dramedy-film starring Billy Crudup, as well as establish itself (in Geltner’s estimation) as one of those generational works of fiction, like Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 or Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five, which most serious readers of the time would either read or feel that they should.

Jesus’s Son (1992), for all its extremities of comedy, violence, and gothic gruesomeness, spoke from the heart of a believable life, or from a believable nightmare of one. In one story, a man enters an emergency room with a knife buried in one eyeball and says: “I can see. But I can’t make a fist out of my left hand because this knife is doing something to my brain.” In another, the narrator is more afraid of his family than he is of running away from them: “I didn’t want to go home. My wife was different than she used to be, and we had a six-month-old baby I was afraid of, a little son.”

As Geltner describes, these stories that Johnson “had first scribbled into his notebook in Iowa City in the ’60s appeared on the shelves of bookstores twenty years later, a new generation was grabbing for the steering wheel of American culture, one with anew sensibility. The old rebellion had been against the army, the government, and the flag. The new rebellion focused on corporations, greed, and the singular pursuit of money and status.… The kids who gobbled up Denis’s stories in the ’90s were an alienated, nihilistic species who wanted to separate themselves from the entire structure itself.” Johnson connected with kids who wanted to drop out of the culture as Johnson himself had. Drugs, car crashes, felonious assaults, and murders most foul—Johnson managed to bring poetry to the worst places in which he had ever gotten himself lost, like an urban-alleyway version of a high fantasy trilogy. Jesus’s Son, in its dark weird way, was escapist.

As a poet and novelist, Johnson rarely placed a foot wrong; he reserved his most egregious missteps for real life. After Jesus’s Son, he continued steadily producing well-regarded books and stopped running away from those closest to him. He softly converted to Christianity, and homeschooled two daughters from his third marriage, which lasted until he died. He produced the sort of big, ambitious mid-career books that often ruin American writers, receiving the National Book Award for Tree of Smoke (2007)—a decades-spanning depiction of rogue CIA ops in Vietnam and the Philippines, for which he resurrected the dissolute brothers James and Bill Houston from Angels. Even his smallish follow-ups to that big serious-looking book, such as Train Dreams (2011), a Cormac McCarthy–esque story of ghosts, railroads, and wolves set in northern Idaho, proved uniquely memorable. His finest and most entertaining short novel—Nobody Move (2009), published as a monthly serial in Playboy—is the fastest funniest novel Elmore Leonard never wrote, with all of Johnson’s most brilliant narrative skills on full display. He should have lived to write more books like this one. He didn’t.

Diagnosed within liver cancer in 2015—quite likely the result of living with hepatitis C contracted during his years of drug use—Johnson moved back to northern California with his third wife and daughters, where he continued writing. He made some small efforts at reconciling with Morgan, and even had time to correct the proofs for his final book, a beautiful collection of short stories titled The Largesse of the Sea Maiden, which contained his most memorable assessment of a writer’s life—or, perhaps, simply his writer’s life:

I’ve gone from rags to riches and back again, and more than once. Whatever happens to you, you put it on a page, work it into shape, cast it in a light. It’s not much different, really, from filming a parade of clouds across the sky and calling it a movie—although it has to be admitted that the clouds can descend, take you up, carry you to all kinds of places, some of them terrible, and you don’t get back where you came from for years and years.