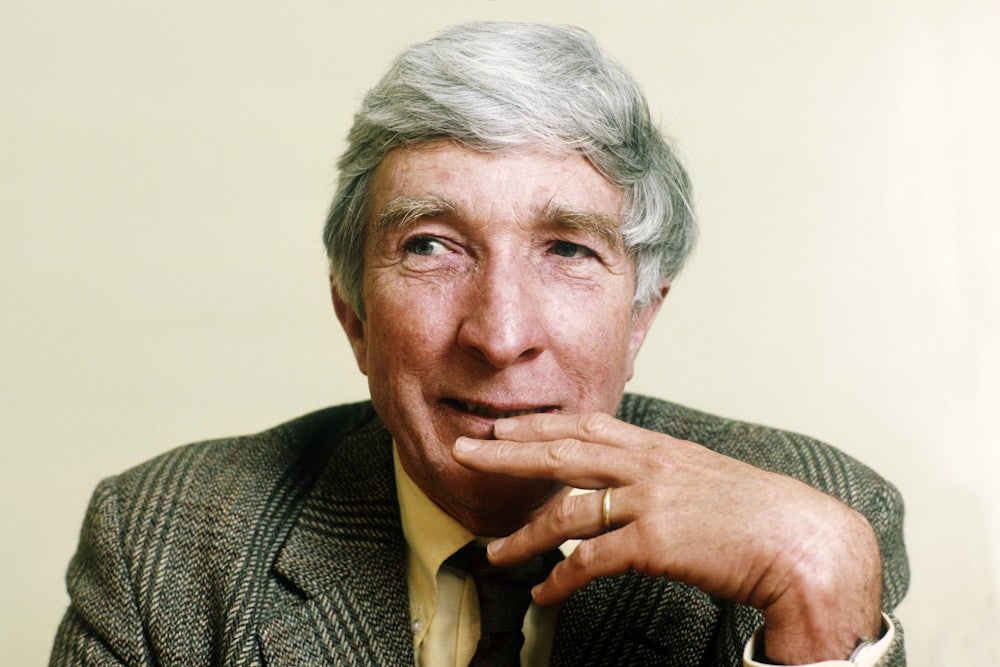

As a producer of sentences, paragraphs, and pages worth reading, John Updike was voluminous. Over the course of his life he steadily, industriously, and almost magically produced several dozen big (and even when small, dense with imagery and intelligence) volumes—novels, collections of short stories and poetry, several large blocky compendia of his book reviews and occasional pieces (most of which originally appeared in his literary home from home, The New Yorker), two books of art criticism, a surprisingly diffident and unlikable memoir, and even a few books for children. From the time John Updike awoke to his career, as a young man, he never seems to have passed a day without sketching friends and family, writing books, reading books, and writing books about reading books.

In this huge attractive new selection of his letters, Updike’s appreciative readers can now pass amiably through the corridors of prose that Updike wrote to friends and family when he wasn’t writing books. Unsurprisingly, the most common topic of discussion in them is either the books he’s writing or the detailed things that happened to him in life that, eventually (if they tested well enough on the rudimentary epistolary page) could eventually be turned into more books.

One of the most enjoyable and absorbing qualities of his fiction was the way Updike could transmute every mundane common human event—sexual activity, news bulletins, weather patterns, and all the diurnal seethe and pop of collective American life—into something elegant and entrancing. To his mother alone, Linda Grace Hoyer Updike (whose youthful failures to sell her own fiction had inspired Updike both to write and to never be dismayed by the possibility of failure), Updike wrote more than two thousand notes and letters—and this was to a woman who lived so close by that Updike could drop by every year to put up her screen doors and windows.

James Schiff, the editor of this doorstop-size book of happily burbling letters and postcards, estimates Updike produced upward of 25,000 letters and missive-like jottings over his lifetime. Collectively, they don’t express urgency so much as a blithe acceptance of almost anything that could be transformed into finely detailed prose, as in most of the letters he wrote to his family back home in Plowville, Pennsylvania, in the early years of his marriage to Mary Pennington:

Such an action-packed week I can’t believe I forgot to write you yesterday. Last Monday I went up on the train to Cambridge, Ann Karnovsky drove me out to Ipswich, and a tall, fur-coated, initially austere lady name of Madeline Post drove us around to look at apartments and houses. Only one apartment; huge, but richly furnished, and the nervous owner wanted $200 per month. Next, we looked at Little Violet, a 5-room house, with barn, carport, study, and 2 acres, for $150. We never got inside Little Violet, it being locked and the real estate agent lacking keys. I just looked into the windows. I couldn’t see much except the little room with white shelves and white marble floor that I envision as my study. The barn seemed very pleasant too. Then we looked at some houses to buy, all of them full of young pioneer women raising dozens of children in the midst of more litter and television sets than I ever saw. We are taking Little Violet; the lease should arrive soon, and we’ll move around April 1st. Seems scarcely credible.

Updike’s longest letters, especially those to his family, don’t respond to problems, or attempt to resolve conflicts, or even address the practicalities of replacing screen doors; rather they are replete with Updike’s accounts of things seen, actions completed, memories recalled, and, in the case of letters to his lovers (there appear to have been a lot of them), recollections of trysts past and greedy anticipation of trysts to come.

The letters are almost exhaustive accounts of one man’s pleasures—a man who seemed to enjoy every good meal, every conversation, every dalliance, every book publication and correction of proofs, every cocktail at the neighbors (whether the husbands were home or not), every excursion as a family man or a literary ambassador, and the birth of every son, daughter, grandson, and granddaughter. Updike didn’t simply compose books, letters, and essays; he recorded the accumulation of pleasures that could themselves be turned into pleasurable sentences and paragraphs.

Updike was born and raised in Berks County, Pennsylvania. His early life was modest, but he received lavish encouragement for his gifts as the only child of two intelligent parents, with two sets of intelligent, attentive grandparents. After graduating from Harvard, he spent a year at the Ruskin School at Oxford University (a period beautifully portrayed in his early short story “Still Life”), and later spent another year in London with his family.

A talented visual artist who grew up adoring the newspaper comics pages, Updike often wrote youthful fan letters to the likes of Milt Caniff (writer and artist of Steve Canyon and Terry and the Pirates) and Harold Gray (writer and artist for Orphan Annie). These letters are filled with compliments and often request free samples of their artwork. (“Milt Caniff is the best cartoonist in the world.” “Orphan Annie is, and has been for a long time, my favorite comic strip.”) This unreservedly admiring approach to writers remained an aspect of almost all Updike’s letters to friends and family when commenting on their stories and novels. (Both Updike’s mother and his eldest son, David, would eventually publish stories regularly in The New Yorker.) And most of Updike’s many hundreds of fiction reviews for The New Yorker were rarely, if ever, mean, harsh, or vindictive.

When Updike started working for The New Yorker as a young man just out of college, he was considered far and away the magazine’s best composer of short, observational pieces for a section called “Talk of the Town”—and the experience was perfect for exercising his innate, on-the-periphery, always-whimsical-about-human-nature viewpoint. As Updike’s biographer, Adam Begley, described it:

Updike remembered three types of Talk story: “interviews, ‘fact’ pieces, and ‘visits’” … and visits became his specialty. He preferred them because they required “no research and little personal encounter.” He developed the knack of planting himself in a particular place—Central Park, the cocktail lounge of the Biltmore Hotel—and simply looking and listening, making himself utterly receptive to sensory impression, noticing everything. Having soaked up the ambience, he put his writing skills to work: “An hour of silent spying” was followed, as he put it, by “two hours of fanciful typing.” (The average Talk piece was seven hundred to eight hundred words.) He made the job of translating his perceptions into “New Yorker-ese” look effortless.

At one point, early in his tenure as a commissioned writer with his own desk and typewriter at the magazine, he produced so many pieces that he wrote home: “I’m way over a month ahead on my salary.” Finding subjects was never a concern for Updike—everything he saw, encountered, and did seemed perfectly useful material; and when he eventually came up with his alter ego, the self-involved and always about to put his foot in his mouth Henry Bech, Updike could do an interview about one of his books, produce a story about Bech giving a similar interview, and then shoot off several letters about the process of turning Updike into Bech and back again. A little life went a long way for John Updike.

Updike was such an easily oiled and productive prose machine that his work never grew stale or tired; instead, as the decades rolled on, he even got better, publishing his best novels in the 1980s and ’90s, such as the last two Rabbit books, Rabbit Is Rich and Rabbit at Rest, many of his best short stories, posthumously collected in his emotionally moving My Father’s Tears, and even his finest poetry.

After abandoning the Manhattan life and the “nicest job I ever had” at The New Yorker in 1957, Updike relocated his family to the less conspicuous pleasures of suburban life. Moving to Ipswich, Massachusetts, with his wife and growing family, he wrote several hours a day, continued selling regularly to The New Yorker, and spent his remaining free time going to parties with neighbors and sleeping with the neighboring wives. Like many young men after the war, he found that the most adventurous life available to him turned out to be an ocean of bedrooms. He slept with so many local wives, in fact, that one woman made the bold claim that she was probably the only woman in the area he hadn’t slept with.

Soon the adolescents and young men he wrote about in his early fiction—who suffered a surfeit of faithfulness to the neighborhoods they grew up in, as in the elegiac Olinger (pronounce “Oh, linger!”) stories—gave way to married men with kids who weren’t faithful to anyone. And at the end of this personal road of sexual experimentation lay the start of one of Updike’s richest fictional veins—Rabbit, Run, which begins with the central character, Rabbit Angstrom, running away from his too-sedate and ordinary young family, seeking to regain the always-new pleasures of his youth.

Many of Updike’s

midlife letters delineate how his early interest in sex developed into an

excessive one, up to the point where he is writing several current lovers

simultaneously, while trying to arrange trysts with former lovers and

beginning a long passionate affair with Martha Bernhard (soon to become his

second wife) at the same time he is considering invitations to sleep again with

his first wife, Mary. The letters include passages such as this one to Martha

Bernhard: “My fingertips smell of you; how can that be? And a taste, remotely

minty … I wonder, will I ever be able to suck hard enough to please you?” Or this

to one of his Ipswich lovers, after catching up with her several years after he

moved away: “I loved being able to drive your Mazda and able—please don’t find

the parallel insulting—to elicit pleasure from your body and mine.” As he

argued to one lover in the mid-1960s, recreational sex had the advantage of

establishing the sort of clarity and focus that usually got lost in family

life; it blocked out competing interests and concerns (yard work, school fairs,

mortgage) and became entirely about itself:

It occurred to me last night, in bed by 10:30, that our sex is so important, my incompetencies bulk so large, because it’s what we do; in a marriage these ups and downs are easily absorbed in the business of making a household and being a couple in public.… Oh Joan, you put it so beautifully, saying that if we don’t make each other happy we should end it. Why did my heart quail at such simplicity? Perhaps because I am unhappy away from you in rough proportion to how happy I am with you, which is very; that I, who formally believe that life is dialectical, and lived in tension, seem to be the one having difficulty with our existence in secret, surrounded by blind gossip, interwoven with our spouses and their libidinous and physiological ups and downs, and now with our intermixed children—how strange and sweet and yet disquieting.

From these samples of Updike’s sexual correspondence (they appear to have been mercifully truncated and selected), Updike wrote some of the most detailed, reasonably thought-out, and unromantic letters ever composed by a major writer; and placing them against those of, say, Flaubert or even Chekhov might make it seem as if he were both colder and more intrepid in his infidelities, as if he were simply punching out numbers on bingo cards. The biggest disappointment of the letters is that the writer himself is never quite so endearing as the many wonderfully selfish characters he created from his own cloth, whether it’s the candy-chomping Rabbit Angstrom or the sexually uninhibited witches of Eastwick. He managed to create memorable, even likable characters who suffered from the worst human frailties, from gluttony, selfishness, and unfaithfulness to a failure to live up to the best ambitions they harbored for themselves.

While Updike’s life and creative work focused on the people, living rooms, bedrooms, and streets of the middle American towns and country clubs where he lived, he steadily reviewed for The New Yorker hundreds of books on a wide variety of subjects while spending more time and attention than any normal reviewer could normally afford. He turned down a request from Philip Roth to provide a few thousand words of introduction to a slender volume of stories by the great Polish writer Bruno Schulz, on the grounds that, as he wrote Roth in 1978:

To do it right, I would have to read all of Schulz in English and maybe acquaint myself with the Polish/Eastern European scene far better than I am.… I introduced Henry Green a while back out of love, paying an old debt; with Schulz I would have to work up the debt, the love, and at this moment, feeling harried and fragmented, I don’t want to commit myself to such a working-up. Please forgive me.

For Updike, writing prose about anything (especially other books) seemed commensurate in terms of energy with the actual living of life; and yet for all his attention to details, Updike’s interest in the political world was limited. He rarely offers much in the way of pronouncements about national or international politics (though he is a constant critic of the visual ugliness of American landscapes and culture), and on one of the rare times he did offer a political opinion, it embroiled him in the sort of conflict he most hated—one that distracted him from his work.

In 1967, Updike contributed a brief “position” paper to a book titled Authors Take Sides on Vietnam, in which he credited “the Johnson Administration with good faith and some good sense,” and seemed surprised that such a mild position could inspire so much outrage. (Of course, what he didn’t seem to understand was that any “mild” position on such a ridiculous and violent war would certainly piss off anybody who was paying attention.) At the same time, his most controversial (and least interesting) novel, Couples, was inspiring similar levels of a different type of outrage. Like that novel’s suburban sybarites and partner swappers who blithely carry on their bedroom games through the Kennedy assassination and civil rights demonstrations, Updike rarely shows much concern for life as it is lived outside his limited social orbit; and he was always a bit dismayed to find himself being observed by the world as acutely as he observed it. “Dear Plowvillians,” he wrote to his family back home in 1968:

The appearance, today, of my somewhat fat and evil face on the cover of Time, with the attendant chunk of Timese inside, has produced in me a strange physical reaction; I feel quite weak, drained by these weeks of attention, and rather nauseated.

There was certainly something about Updike that upset many readers (especially women), but the person who always seemed the most “nauseated” by Updike was probably Updike himself—who rarely seemed to inhabit any male, middle-class characters without exposing almost every one of their unenviable traits. From Updike’s self-obsessed, careerist-author Bech to the always prepared-to-bolt Rabbit Angstrom, to his numerously and obsessively philandering husbands, Updike rarely (if ever) created characters who could be called heroic, upstanding, or admirable, and yet as he grew older and strayed less often from his second, apparently happier marriage, his literary imagination grew more adventurous; he depicted sex-driven suburban cabals (in Witches of Eastwick), wild rich passionate jungle adventures (in Brazil), and one of the most sympathetic pictures of a homegrown American terrorist (in Terrorist) that probably could have been published in the increasingly righteous post-9/11 America.

As his novels and poetry got better, his letters grew less concerned with arranging sexual calendars and more concerned with keeping in touch with fellow writers, such as Philip Roth and Ian McEwan, and arranging visits to the grandchildren. His cancer diagnosis came, sudden and surprising, near the end of 2008, when he was 76, and he died—still writing and reading and correcting book proofs—only a couple of months later. Perhaps he never stopped writing because when he was writing he never grew old; and it is that ageless (and never at all “upstanding”) Updike who comes back to life again in this voluminous, Updikean-size collection.