In many of the international news outlets around the world, you will find a section devoted to covering current events in the United States. Aside from just including it in their international coverage, many foreign news outlets devote special attention to U.S. coverage, a testament to the nation’s influence on global affairs. It can also be an interesting window into how journalists not enmeshed in the habits and tendencies of our own media elites view what’s happening in our own backyards.

Within the last two weeks—not to mention the past year—the world has been paying careful attention to what’s happening on these shores. Since 2026 began, international outlets have been fixated on whether the U.S. government plans on throwing the world into deeper chaos. Some have been prophetic, such as the French newspaper Le Monde’s December 1, 2025 editorial, “Donald Trump’s interference and incoherence on the American continent,” which commented on Trump’s insistence on seizing the Danish territory of Greenland. Others include the more humorous headline from the Dutch satirical newspaper De Speld (“The Pin”) that, in traditional Dutch bluntness, did not hold back: “Who Is J.D. Vance, the First bitch Behind President Trump?”

More recently, however, the commentary on Trump has shifted from ridicule to genuine concern about the future. A more moving cover image published on January 28 by the French magazine Charlie Hebdo depicts an ICE agent dragging the bullet-riddled body of Alex Pretti to a pile of corpses, leaving a trail of blood that resembles the American flag. Although Pretti was murdered by Customs and Border Protection agents (identified by ProPublica as Jesus Ochoa and Raymundo Gutierrez), the point is pretty clear: The Trump administration has shown no remorse for killing Americans protesting against his deportation policies. Most of all, European media outlets have hyper-focused on Trump’s threats to invade Greenland and break up NATO.

In Latin America, news outlets have anxiously commented on growing American military aggression in the region. In Mexico City, the paper of record La Jornada includes a series titled, “Caracas Under Attack and the Return of Interventionism.” Historians Miguel Tinker Salas and Victor Silverman, both at Pomona College, co-authored an op-ed for La Jornada telling readers that Trump’s foreign and domestic policies are designed to distract from his failing domestic policies. Drawing from the old Kentucky mining song “Which Side Are You On?” Tinker-Salas and Silverman noted that the battles in Minneapolis have exposed the failures of Trump’s immigration policies.

North of the border, Canada’s paper of record, The Globe and Mail, has chronicled everything from Trump’s ludicrous threats to absorb the Great White North to his damaging tariff policies. Others, like Daniel Siemens, stated more bluntly, “Are ICE agents modern-day Nazi brownshirts?”—calling for an end to the paramilitary organization.

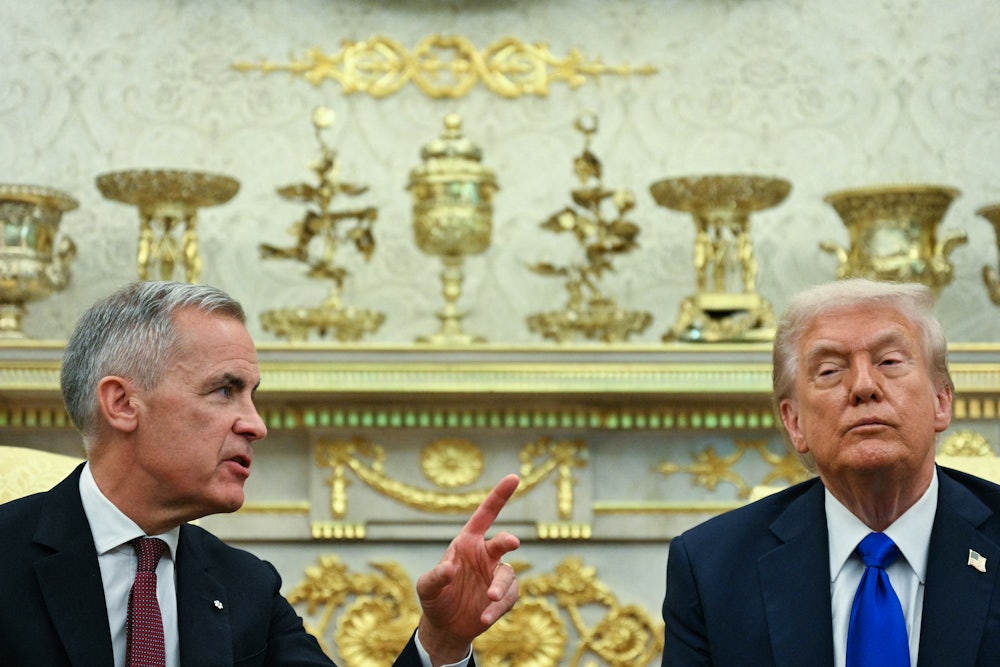

Most of all, Canadians have rightly reacted with anger to the provocations of Donald Trump, of which they have a close-up view. As one of America’s closest allies and largest trading partners, Canada has seen a significant drop in cross-border traffic. Trump’s flippant use of tariffs to punish Canada not only contradicts his own previous revision of the North American Free Trade Agreement—the 2020 U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement, which was cobbled together during his first term—but has left permanent damage to foreign trade relations. Along with his childish labeling of Canada as a “fifty-first state,” Trump’s use of tariffs to blackmail foreign leaders led Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney to call for a realignment in the geopolitical order, in his speech on January 20 at the World Economic Forum in Davos.

Calling out Trump’s disregard for the rule of law, Carney told world leaders that such behavior has consequences: “If great powers abandon even the pretense of rules and values for the unhindered pursuit of their power and interests, the gains from ‘transactionalism’ will become harder to replicate. Hegemons cannot continually monetize their relationships.”

No matter where you go in the world, chances are there’s a news outlet asking readers the same question: “What is going on in the United States—and how will this affect us?”

Some, like Globe and Mail columnist Konrad Yakabuski, are already looking ahead to the midterms for an answer. In a pointedly written piece, “Can Democrats slam the brakes on Trump’s rogue presidency with a big midterm election win?” Yakabuski, hesitant to indulge advocates’ calls for instance for abolishing ICE, called on Democrats to be pragmatic about the battles they pick in the midterms: “One can only hope that, sooner rather than later, enough average Americans will decide they have had enough of Mr. Trump’s chaos. Until then, however, Democrats will need be strategic about choosing their battles.”

While the question of Democratic strategy for the midterms remains undecided, Yakabuski’s article makes clear that, even outside the United States, many are anxiously watching the midterms to see how it will affect them.

Midterms are often seen as a referendum on the status of a sitting president. This year the midterm elections pose a greater question: Can the United States survive another two years of Donald Trump? And will the rest of the world be able to bear it?

Here, Democrats need to make the case to voters that Donald Trump poses an existential threat to the U.S. and its reputation abroad. With the shooting of several protesters by Immigration and Customs Enforcement and Customs and Border Protection agents and the murder of dozens of migrants in detention centers, human rights are on the ballot this November. With the destabilization of the global economy and rising prices thanks to Trump’s tariffs, the ability of working-class Americans to survive is an issue this November. Come November, Democrats have an opportunity—or, really, an obligation—to repair the U.S. and its image abroad.

Eighty-one years ago, on April 25, 1945, delegates representing 50 nations convened in San Francisco to organize what would become the United Nations. Building from the ashes of World War II, the delegates came together to form a new organization with the stated goal of preventing another world conflict and fostering good relations between nations. When President Harry Truman spoke before the conference, he left these words with the delegates:

Let us labor to achieve a peace which is really worthy of their great sacrifice. We must make certain, by your work here, that another war will be impossible.… Nothing is more essential to the future peace of the world, than continued cooperation of the nations, which had to muster the force necessary to defeat the conspiracy of the axis powers to dominate the world.

While these great states have a special responsibility to enforce the peace, their responsibility is based upon the obligations resting upon all states, large and small, not to use force in international relations, except in the defense of law. The responsibility of the great states is to serve, and not dominate the peoples of the world.

Truman’s words, while inspiring, did not ring true; the postwar order was still marked by violence and global inequity. While decolonization was in some cases achieved peaceably, for instance in the U.S. departure from the Philippines, it still arose too often from conflict, as it did in many parts of Africa and Asia, most notably Vietnam. Truman found himself mired in conflict once again five years later, when he sent U.S. troops to defend South Korea from the North’s invasion.

In Latin America, U.S. policy during the Cold War was far from peaceful. Foreign interventions, such as the CIA’s coup in Guatemala under Eisenhower in 1954, Kissinger’s colluding in Chilean President Salvador Allende’s murder in 1973, and Reagan’s support of the Contras in the 1980s, epitomized a long history of the U.S. meddling in Latin American affairs.

Greg Grandin, a longtime expert on U.S. interventionism in Latin America, wrote an op-ed in The New York Times putting Trump’s kidnapping of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro within the context of U.S. foreign relations with Latin America. In some ways, Grandin argues, Trump’s behavior falls into a long pattern of U.S. presidents using Latin America as a stage for flexing American power: “Often during times of global turbulence, like the moment we now find ourselves in, presidents seek safe harbor there. Latin America was where U.S. leaders have projected power beyond their borders not only with brute force, including all those coups Washington orchestrated, but with moral suasion as well.”

Yet Grandin also believes there was a period in U.S. history where the American government treated Latin America on an equal footing. In his new book America, América, Grandin asserts that the “good neighbor policy” under President Franklin Roosevelt marked a decade of peace between the U.S. and Latin America. For Grandin, it was thanks to the good neighbor policy, which restrained Roosevelt from intervening in the region, that FDR was able “to assume the moral authority to lead the fight against world fascism.”

In this regard, Truman’s statement to the U.N., following in the footsteps of his predecessor, underscored America’s desire to be a leader of liberal ideology in the postwar order—one that created the America’s long-standing reputation as an advocate of peace. Now it’s these multilateral institutions that are currently under threat thanks to the Trump administration.

In the wake of the invasion of Venezuela, human rights violations perpetrated during deportations, destruction of decades of good relations with European leaders, and economic mistrust caused by his own tariff policies, Donald Trump has managed in one year to destroy much of America’s reputation abroad.

So how can Democrats, either incumbents or challengers, articulate a platform this November that unseats Republicans? While Trump bears the lion’s share of blame for the woes of his presidency, Republican members of Congress are also guilty of having unquestioningly bowed to Trump throughout his second administration, relinquishing their oversight in return for the promise of loyalty. Democrats will have to frame this election as the existential crisis that it is: With Trump and Republicans in power, the United States is in decline.

When I spoke with Grandin, I asked him what has come out of the turbulence of the past year. In some ways, he noted, the failure of the current administration offers a rare opportunity: “The Trumpists have done us a favor by insisting on the bankruptcy of the post–Cold War neoliberal consensus. What they offer in its place of course is barbaric: a garrisoned, murderous tribalism.”

When I asked him what is needed in its place, Grandin offered the following: “To defeat that vision, we need to put forth a universal humanism—an anti-fascism that understands that you beat fascism by fighting for social democracy—for social and economic rights.”

I put similar questions to another famed historian on Latin America, Miguel Tinker-Salas. “I think the larger issue,” Tinker-Salas argued, “is that we tend to present Latin America as an adversarial relationship. The immigrant is an adversary, the country is an adversary, Mexico is trying to take us over, Venezuela’s trying to bring in foreign powers. Well, what if we flip that script? What if we looked at that these are our allies and that we could consider the possibility of it reengaging with the region?”

It’s a compelling paradigm shift, one that has been absent from U.S. foreign policy for some time: Let’s treat our neighbors with respect. Much like Grandin’s point about Roosevelt’s good neighbor policy, there is a need to reestablish foreign relations with our neighbors on equal terms.

Already, the consequences of Trump’s retaliatory economic policy have forced our former trade partners to form new trade relationships, notably with China. “At the same time,” Tinker-Salas argues, “China has stepped in to Latin America. China is the number one trading partner for Brazil, for Argentina, for Chile, for Peru. The building of the Deepwater port in Peru that will connect by rail to Brazil opens up for China a whole area of South America.”

In addition to repairing damaged relationships, the U.S. needs to address its policies at home. A key part of this platform needs to be the dissolution of ICE as an agency and the dismantling of Trump’s global deportation project. As an agency that has become fundamentally loyal to Trump, its existence would hinder progressive policies and foster deep suspicion in our allies abroad. Dismantling an agency that most associate with violence and human rights violations will go a long way toward improving America’s image abroad.

Changes to U.S. domestic politics are part of the greater reshaping of U.S. foreign relations. This is especially true of Trump’s current deportation policy, his flagrant dismissal of civil rights, and his discriminatory immigration ban that targets immigrants of color. Meanwhile, the human rights of migrants in the United States, the constitutional rights of Americans to assembly peacefully, expose corruption, and speak freely, are all freedoms under attack. As Tinker-Salas and Silverman wrote in their op-ed for La Jornada, “What the protesters are proclaiming in the streets are the human values that Trump and the global right are trying to erase. What will happen is yet to be determined, but we know which side we are on.”

As law professor Mary Dudziak points out in her landmark study Cold War Civil Rights, discriminatory U.S. domestic policies during the Cold War, such as racial discrimination against Black Americans, vastly undermined U.S. foreign relations. At a time when U.S. ambassadors touted “American values” of democracy and freedom in contrast to the Soviet Union, foreign observers, especially those in African states, found it hard to swallow when Black Americans were excluded from participating in the American political system. This same argument still applies to U.S. treatment of immigrants. If the Trump administration continues to wantonly kill protesters, such as Renee Good and Alex Pretti, and does not prosecute the agents responsible, it ruins that credibility of the country and its government.

Democrats need to not only rethink the existence of ICE as an institution but to rapidly prosecute agents who have violated law enforcement practices as in the murder of protesters. It needs to end the deportation of immigrants to torture facilities like CECOT, in El Salvador, and release those who were wrongfully detained without any due process. Moreover, it needs to permanently overturn the immigration travel bans that reinforce race-based discrimination. Otherwise, it is hard to take the United States seriously as a defender of human rights. Injustice in the U.S. harms not only American citizens but also America’s relations abroad.

Lastly, in the long term, reform will also mean committing more resources than before to supporting global human rights; this necessarily includes rebuilding USAID to repair foreign relations with developing states. USAID not only emblematized the spirit of the Kennedy administration’s New Frontier program, but also signified a means to establish goodwill relations among other states. While USAID was created in a Cold War context of opposing the Soviet Union by American soft power, USAID not only helped foster good relations but also benefited the U.S. by supporting public health programs and cultural exchanges. A new USAID could offer the chance to repair shaky relations with developing nations that have long been exploited for natural resources.

This November, the midterm election will represent a turning point in American history. If Republicans keep control of Congress, it will lead to two more years of unchecked power for Donald Trump—and more chaos for the rest of the world—especially if the Supreme Court continues to take a half-hearted approach toward enforcing the rule of law to appease Trump.

A Democratic victory in the midterm election would not only mean a fighting chance to stand up to the Trump administration, but also the possibility to rebuild the shattered credibility of the country. Otherwise, it will also mark the end of stable foreign relations with old allies who, after facing a year of uncertainty, will form new alliances as the U.S. sinks deeper into isolation. To again quote Carney, the United States can no longer “live within the lie” that the world depends on it.