Early last November, as Alvaro Luna Hernandez, age 73, awoke from uneasy sleep, numbness radiated from his hands and feet, and he realized he could no longer walk. He tried hoisting himself up within the confines of his six-by-eight-foot solitary prison cell, and fell to the ground. This was neither his first nor his last fall; the worst occurred in the shower, on November 17. There was nothing to hold onto—no “handicapped elder-accessible shower,” if you prefer lawyer-speak—even though 16 percent of Texas’s prison population is 55 or older. And so, when he fell, he hit his head.

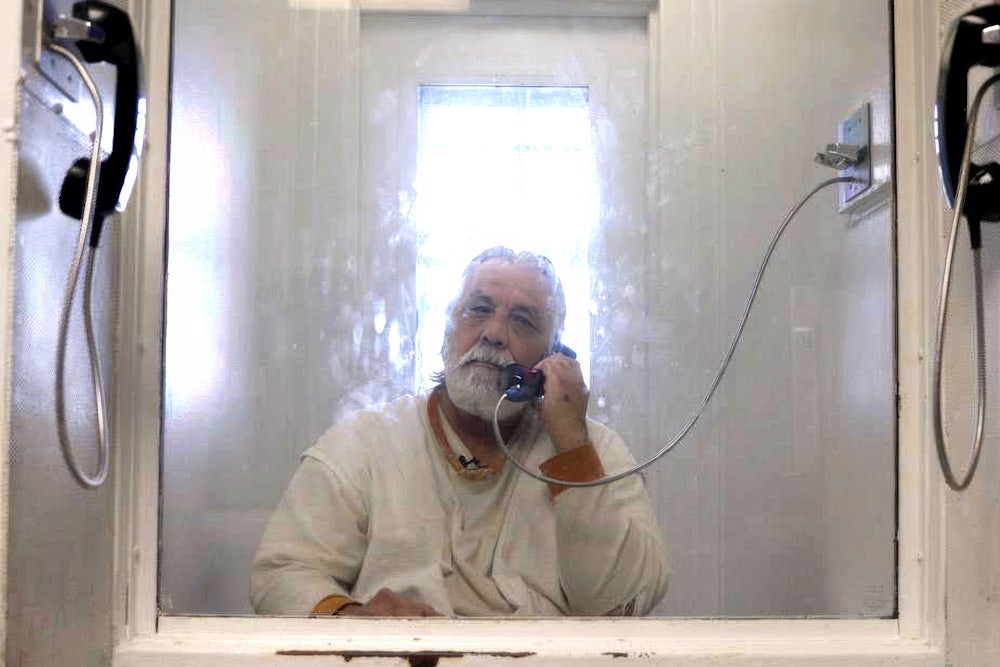

The accident capped off roughly two years of creeping bodily deterioration. Hernandez—better known as Xinachtli (pronounced Shin-atch-tlee), Nahuatl for “germinating seed”—is a renowned Chicano activist who has been held in solitary confinement for 23 years, most of which he has spent in the notorious William G. McConnell Unit in South Texas. The facility isn’t fully air-conditioned, even though summer temperatures can reach upward of 100 degrees. When it rains, Xinachtli recently told a Texas court, his cell floods. He stores his important belongings—paper documents, snacks—in peanut butter jars to keep the rats from chewing through them.

These conditions, especially for a man in the twilight of his life, have only compounded his health problems, Xinachtli and his supporters have argued. Despite multiple requests for care throughout 2025, court records show, “These requests have been ignored, delayed, or obfuscated by [McConnell Unit] officials.” By early January 2026, Texas Department of Criminal Justice officials had still yet to communicate a complete diagnosis, leaving Xinachtli and those who care for him entirely in the dark about his health—and how long he has to live.

Xinachtli’s case dates back to the doldrums of left-wing politics in Texas, when the hegemony of the Texas Democratic Party reached a screeching dead end and far-right politics began its rapid ascent. From the late 1960s onward, Black and Chicano groups sought new forms of political protagonism, challenging the white Democratic establishment and combating the system of racist policing that defined Texas from its frontier days to its transition to petrostate-within-a-state.

By 1994, three years before Xinachtli was sentenced to 50 years in prison for the alleged aggravated assault of a sheriff (Xinachtli and his supporters maintain he merely disarmed the officer, fearing for his life), Texas liberalism was in free fall. The state’s Democratic Party was unable to maintain its winning coalition of white liberals, organized labor, Black and brown activists, and “Jeffersonian” conservatives who had dominated local politics since Reconstruction. Its institutional heavyweights mutated into Republicans proper or the “tough-on-crime” blue dogs we know today.

Now, a coterie of activists has rallied behind Xinachtli’s cause, citing his history of advocacy against police violence as reason for the state of Texas’s negligent treatment. For them, Xinachtli’s case, and his status as a “political prisoner” and well-known jailhouse lawyer, stands for a legacy much greater than the sum of its parts, and by linking themselves to it, they’re reconnecting to a lineage of left-wing activism long presumed dead—even nonexistent—within the state. “Sometimes you hear a story and you just know it’s part of you,” said Maria Salazar, age 25, a member of Xinachtli’s support committee. “Xinachtli’s struggle just seemed like part of me.”

At times, Xinachtli’s life sounds like something out of a storybook—even a “ballad,” as CounterPunch referred to it in 2011. Here’s an all too brief summary: In 1968, at age 15, Xinachtli witnessed the police killing of his friend Henry Ramos, who was 16 years old at the time; the case was noted in a 1970 United States Commission on Civil Rights report, “Mexican-Americans and the Administration of Justice in the Southwest.” At age 22, he was accused of a murder he didn’t commit and briefly escaped from jail before being sentenced. At age 26, he was party to the historic Ruiz v. Estelle civil rights case, which ruled that Texas prisons violated the Eighth Amendment and constituted “cruel and unusual punishment,” and also helped to lead a strike from within prison walls to coincide with the trial.

Finally, in 1991, he was released on parole, though his co-defendant’s conviction on the same evidence was fully reversed and dismissed in 1979. Five years later, Xinachtli was rearrested by the sheriff back in his hometown, the small railroad water stop of Alpine, in far West Texas, but not before he helped organize a historic support campaign in Houston to free the death row inmate Ricardo Aldape Guerra, an undocumented immigrant wrongly accused of murdering a police officer.

Guerra was successfully exonerated mere months before Xinachtli’s conviction, the activist’s hair already greying at the time of his second arrest. There’s a sick irony to the fact that others have had to create the same support structure for him. His life has been defined by run-ins with the law—and critical civil rights victories over the Texas government, breaking decades of entrenched precedent. It’s perhaps of little surprise that prison officials saw fit to segregate him from McConnell’s general population for the past 23 years, at first alleging ties to gang activity, and later an apparent “mental health security designation,” both of which also impacted his ability to make parole or receive a medical release.

In December 2025, Amnesty International published a statement demanding the state of Texas “ensure that all of his human rights are respected, protected and fulfilled as required of the Texas government under international law.” It’s a race against the clock—and prison authorities—to avoid what Sandra Freeman called “death by incarceration.”

In a typical civil rights court case, “There is an injury, an event that ends, and then a court case is filed,” Freeman told The New Republic. But “in this particular case, the injury is ongoing, the retaliation is ongoing,” which makes the arguments for and against Xinachtli far more slippery.

For example, back in December, he was briefly transferred to a hospital in Galveston following a weeks-long pressure campaign led by his support committee, and his condition slowly but surely improved. To keep a transfer back to solitary confinement off the table, Freeman attempted to file for a restraining order, essentially locking him into his hospital bed. Yet, because he was already in a hospital bed, Assistant Attorney General Vishal Iyer was able to argue in a court hearing that the lawsuit was needless; it was “quite speculative” that Xinachtli would be transferred back to McConnell at all, he said.

Iyer’s second line of argument contradicted the first: There were a “limited supply of these medically available beds,” and “prison authorities should have the ability to assign an inmate” where they saw fit. On Christmas Eve, Xinachtli was transferred to a disciplinary cell at McConnell. Around a week later, they had to transfer him back to McConnell’s infirmary. After yet another pressure campaign, Xinachtli was transferred to yet another hospital, the Carole Young Medical Facility in Dickinson. Iyer will now likely argue for his clients’ qualified immunity, a common method for prison officials to escape accountability. Multiple requests to Iyer and the state Attorney General’s office for comment went unreturned.

Whether by the banal workings of an indifferent bureaucracy or by outright medical neglect, the result feels to Xinachtli and his supporters like a morbid game of cat and mouse. In February, March, and June of last year, various medical staff reported Xinachtli was a “no show” to his medical appointments because there was “no escort” available, according to court records. Meanwhile, in February and September, the official excuse was that Xinachtli “refused” to travel to the clinic. But in a March request for medical care, Xinachtli made the stakes clear: “I am not refusing your care. I cannot walk the mile to the clinic without feeling exhausted and out of breath. I need ‘wheelchair’ aid for my disability.” He cited pain in his kidneys. He began to suffer from incontinence. Between October 2024 and December 2025, he lost almost 100 pounds.

Salazar recalls that, in the latter half of 2025, she began to notice Xinachtli’s usual energetic disposition was muted, as if his mind had caught up to his 73-year-old body and was beginning to slow down. In November, around the time of his fall, Freeman became the first of his supporters to see him in a wheelchair. “It’s just a shocking experience, seeing someone age and decline really rapidly,” she said. Just a few months prior, he had been active and engaged in his case. Now, he had slurred speech; it was clear to her that he was experiencing some kind of cognitive decline.

Dr. Dona Kim Murphey, a third-party medical specialist, conducted several limited examinations of Xinachtli. In a late November phone interview, Murphey reported that he exhibited short-term memory problems, meandering and disorganized speech, and an inability to recall his own age, stating he was 53 instead of 73. On December 2, at an in-person session, Dr. Murphey performed a neurological examination of Xinachtli with limited equipment, imploring prison officials to conduct an “urgent brain and spinal MRI” and lab tests, adding that—in the best-case scenario—Xinachtli may be able to walk again after “months of inpatient physical therapy.”

Finally, after months of delay, the Texas Department of Criminal Justice provided Freeman with Xinachtli’s complete medical records. What those documents revealed was stark: It was as if his entire body was failing at once. Xinachtli had suffered a stroke and a heart attack, and appeared to have a lesion on his liver, possibly cancerous; this was in addition to spinal degeneration, heart and kidney damage, prostate damage, and a hernia. This came as a surprise to Xinachtli, who had no idea he’d suffered from a stroke or heart attack.

“We had to have a very hard conversation with Xinachtli about what these medical records show,” Freeman told me. For years, he’d been left in the dark. The news cast Xinachtli’s Christmas Eve transfer in another light: Doctors with access to his medical records knew of these conditions and still transferred him back to solitary confinement. “I don’t understand how they’re keeping him confined like they are unless there’s some other agenda,” Dr. Murphey told me. It only “makes sense if he is actually being politically persecuted. They’re denying him care systematically because of who he is.”

On January 19, Dr. Murphey sent an open letter to medical staff at the Carole Young Medical Facility calling for expedited blood and gastrointestinal tests, given “the chronic medical neglect” Xinachtli had suffered up to this point. If expedited treatment and “more intense level of rehabilitation, and careful dementia risk factor management is not available,” she concluded, “my recommendation is that [he] be urgently released for care in the community.”

It’s difficult to square who Xinachtli appears to be in the eyes of Texas—Iyer referred to him at the December court hearing as having a “long history” of violence and an “association to organized crime”—with the white-haired man in a wheelchair who seemed to shrink in his seat during the court hearings I attended on Zoom. He spoke slowly, clasping his hands together as if for warmth. “A lot of times, revolutionary elders will die, and we will not tell their stories until they die,” Salazar told me. But their memories are all the more precious when they’re alive.