Maybe, this time, rock really is dead. In 2016, the pop charts were ruled by Justin Bieber, Drake, and Rihanna. The year’s most critically acclaimed albums were mostly made by pop stars, rappers, and people whose work loosely falls under the category of R&B. Rock’s entries in the best-of-2016 lists came from legacy acts like Nick Cave and Radiohead; very good younger bands that sound like very good bands from back in the day, such as Car Seat Headrest and Parquet Courts; or people who literally died, like David Bowie and Leonard Cohen, who both made albums about dying.

This is a very good thing, culturally speaking. The national music scene has never been this diverse. Too often, especially in rock’s heyday, it was dominated by acts that made their bones from taking nonwhite music and sanitizing it for white audiences. That tradition undoubtedly lives on, in musicians like Justin Bieber, but the pop charts and critics’ notebooks accurately reflect the American mosaic in a way that they really haven’t before. We may be in the midst of a gigantic leap backward as a country, but at least the music is good. Even the country charts are pretty woke.

In 1972, The Who’s frontman Roger Daltrey sang, “Rock is dead, long live rock.” But in 2016, he told the London Times, “Rock has reached a dead end. … The only people saying things that matter are the rappers and most pop is meaningless and forgettable.” Rock music this year was defined by death, resentment, and baby boomers making one last grasp at relevance, which was most evident in a slew of memoirs by aging rock stars.

Death wrapped its icy claws around 2016 at the start of the year and didn’t let go. Bowie released his final album, Blackstar, on January 8 and died after a long, secret battle with cancer two days later. Blackstar—his most haunting work since the late 1970s and also his finest—felt like a kind of obituary. (It was also accompanied by two genuinely scary music videos.) Only Bowie could echo both Keats and Kendrick Lamar as he morbidly sang about his decaying body and impending demise.

With Bowie, the clues were all there. But with Prince, you didn’t really see it coming. Yes, there were rumors of drug use and an emergency plane landing, but his death on April 21 was a punch in the gut. The greatest songwriter, performer, and musician of his generation, Prince’s music was as idiosyncratic and transgressive as pop music gets. No one wrote about fucking better than Prince, before or since. To label Prince “classic rock” feels sinful: Prince made Prince music, and “Darling Nikki” isn’t exactly blowing up classic rock radio like “Hotel California.” Prince fused multiple genres—funk, soul, R&B, and, yes, rock—without neatly falling into one category. But Prince also marked something of an evolutionary end for rock music: After him, rock stars looked backward more than they did forward, and they certainly looked more to rock’s own past than they did to other genres.

Over the course of 2016, we also lost Eagles frontman Glenn Frey, Jefferson Airplane guitarist Paul Kantner, fifth Beatle George Martin, Earth, Wind & Fire genius Maurice White, prog rock maniac/E in ELP Keith Emerson, Elvis guitarist Scotty Moore, nightmare machine Alan Vega, King Crimson singer/L in ELP Greg Lake, true weirdo visionary Leon Russell, and, most recently, heir to Freddie Mercury’s kingdom George Michael. If you were to broaden the category a bit further, there would be the second-greatest (but most literary) songwriter of his generation Leonard Cohen; poet laureate of the poor but proud Merle Haggard; experimental wizard Tony Conrad; alternative country godfather Guy Clark; bluegrass virtuoso Ralph Stanley; and dap queen Sharon Jones. If you had to sum up what happened in rock music in 2016, you’d say: People died.

If you were a rocker in reasonably good health who put out a reasonably successful record in the 1960s or 1970s and had yet to write a book, chances are you wrote a book or had one written about you in 2016. As the publishing industry has become more vulnerable, it has become more risk-averse. Established names with established audiences—preferably older audiences, who spend money on things like books—have become increasingly valuable. After the success of Bob Dylan’s Chronicles, Keith Richards’s Life, and Patti Smith’s Just Kids, publishers are hot for baby boomer nostalgia, while musicians are just as hot to cash checks. In 2016, Bruce Springsteen, Phil Collins, Brian Wilson, Mike Love, Robbie Robertson, Johnny Marr, and Sebastian Bach all published memoirs—in a few cases, they even wrote them, too.

But, with the exception of Springsteen’s joyous memoir, a feeling of resentment permeates these books that are supposed to serve as well-earned victory laps. The desire to bask in glory turns out to be inseparable from the sense that credit hasn’t been given where it’s due. This curious mixture of self-satisfaction and resentment—call it the baby boomers’ revenge—was reflected in the politics of 2016, which was defined by a reactionary nostalgia that led to the Brexit and the election of Donald Trump, two catastrophic events that came over the expressed opposition of younger generations.

That rock is kind of evil should come as no surprise in the case of Mike Love, who has emerged as the most notorious villain in Beach Boys lore. Love’s Good Vibrations is, despite its title, bitter, angry, cynical, and very direct about its primary purpose, which is to correct the widely held perception that Love is an asshole. The memoir makes the case again and again that Love was the hero of the Beach Boys and everyone else (except maybe Carl Wilson, who is portrayed as having been childlike and naive) was a rogue. Love treats the late 1960s—which is the period we are really talking about when we talk about “The Sixties”—as a bewildering period of cultural decay. Love has little patience for the freaks who surrounded Brian Wilson as he made Pet Sounds and labored over Smile. For Love, the Beach Boys were a quintessential “American” band, devoted to surfing, joyriding, and hamburger stands—something Brian’s sonic experiments didn’t convey.

Love presents himself as a guy who calls out bullshit: He doesn’t let pushy drug dealers and shrinks control his life, like Brian; he doesn’t let other people make all the decisions, like Carl; he doesn’t fuck everything that moves and hang out with Charles Manson, like Dennis Wilson. He is the captain of his angry, angry soul. Love is very open about not really getting or participating in The Sixties. Aside from joining the Beatles to study with the Maharishi and developing an interest in environmentalism, he felt out of step with his times, in large part because the Beach Boys were seen as square. He writes admiringly of Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush—he might not like all of their policies, but they invited the Beach Boys to play for them, and for Love that’s really all that counts.

(This is not even to mention all the horrible things he did in his personal life. I lost track of Love’s wives by page 200. He informs the reader of the death of his biological daughter with a footnote that includes the addendum that he is not and has never been in touch with her son. And on page 16 he admits to using the n-word in high school, but says it was fine because he had an “appreciation—indeed affection—for who they were and what they were all about,” meaning black people.)

The Band’s Robbie Robertson is in many ways Love’s opposite. He’s a careful narrator who is mostly content with giving the fans what he thinks they want: stories about famous people he encountered. His memoir Testimony is what you’d expect from the writer of “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down.” Its prose is literary, precise, and unpretentious, its scenes are well-constructed, and there’s a twinkle in its otherwise clear eyes. But there is quite a bit of score-settling in Testimony as well. If you know anything about The Band’s story after 1976’s Last Waltz, you’d know that it was defined by a bitter feud between Robertson and the group’s other members, particularly Levon Helm, but also Rick Danko, Richard Manuel, and Garth Hudson. Robertson was accused of ripping them off by claiming sole songwriting credit for almost all of the group’s output, therefore securing the lion’s share of royalties—living on easy street while the others scraped by. Robertson was also accused of breaking up The Band because he wanted to become a star, twisting the arms of the other four members who relied on touring to survive.

Robertson sidesteps this extremely fraught history with phony objectivity. The Band’s complicated afterlife is never overtly mentioned in the text, which gives off the impression that Robertson is taking the high road. He isn’t.

Instead, Robertson carefully inserts his version of events. In his rendition, after initially sharing songwriting credit with his band members—and thereby splitting the money—Robertson grudgingly buys it back from them when they’re short on cash. (The implication in every case but Garth’s is that they need the money because they’re addicted to cocaine, heroin, or both.) Similarly, Robertson makes it clear that he was the grown-up of the group, the one who guaranteed they got paid. While the others were crashing cars and snorting coke, Robertson was making sure the whole damn thing didn’t fall apart. (Robertson admits to drug use at the time, but always distances his use of cocaine from that of his bandmates.) Same goes for breaking up The Band—he didn’t do it because he thought his new friendship with Martin Scorsese was going to propel him to (even greater) fame, but because he was worried that if the group kept touring that one of them would die.

It all feels like a rebuttal to his bandmate Levon Helm’s searing autobiography This Wheel’s On Fire. Whereas Helm blamed Robertson’s vanity for The Band’s breakup, Robertson blames Helm’s drug use. “It was like some demon had crawled into my friend’s soul and pushed a crazy, angry button,” Robertson writes.

Phil Collins’s memoir, fittingly titled Not Dead Yet, is largely a response to his status as an avatar of the unhip 1980s. Collins has a sense of humor about it, but Not Dead Yet is nevertheless colored by his perceived rejection by his successors. (Perhaps the cruelest rejection comes from Oasis’s Liam Gallagher, who brushes Collins off as a has-been when he tries to make an introduction.) Collins is far more modest than either Love or Robertson, however, letting Peter Gabriel and his Genesis bandmates take much of the credit for their early 70s success and setting aside his own underrated, trailblazing drumming and production. But Collins, ever the optimist, thinks that history will vindicate him. Near the end of the book, he glowingly relates praise he’s received from rappers like Kanye West. The rockers may have rejected him but even they are dinosaurs now—people like West are the future and Collins knows it.

Springsteen’s book is the best rock memoir published this year, though it is characteristically overwritten in certain places. Here’s Springsteen writing about Elvis’s debut on The Ed Sullivan Show:

THE BARRICADES HAVE BEEN STORMED!! A FREEDOM SONG HAS BEEN SUNG!! THE BELLS OF LIBERTY HAVE BEEN RUNG!! A HERO HAS COME. THE OLD ORDER HAS BEEN OVERTHROWN. The teachers, the parents, the fools so sure they knew THE WAY—THE ONLY WAY—to build a life, to have an impact on things and to make a man or woman out of yourself have been challenged. A HUMAN ATOM HAS JUST SPLIT THE WORLD IN TWO.

Springsteen’s memoir runs hot, as it should, given his penchant for marathon four-hour shows. But it’s also unusually reflective, a book that’s clearly the result of a substantial amount of therapy, much of which related to his relationship with his father, a source of his musical inspiration.

One thing these books have in common is a general ambivalence about the time period their authors are largely identified with. For Love and Robertson, it’s the 60s and early 70s; for Springsteen and Collins the 70s and 80s. These writers know that they made history, but are not quite sure what that history means. They are baby boomers who are abundantly proud of their generation’s cultural achievements but wary of its political legacy.

Rock was not without its triumphs in 2016, however. Bob Dylan won the Nobel Prize in Literature. There was something ironic in Dylan’s triumph, in that Dylan’s influence is not as strong as it once was. Popular music may have superseded literature as a cultural influence long ago, but other genres have supplanted rock, folk, and blues. Dylan’s Nobel Prize win also felt like a belated shot in a culture war that ended long ago—anyone who doesn’t think Dylan’s music should be taken seriously is rightfully dismissed as a crank.

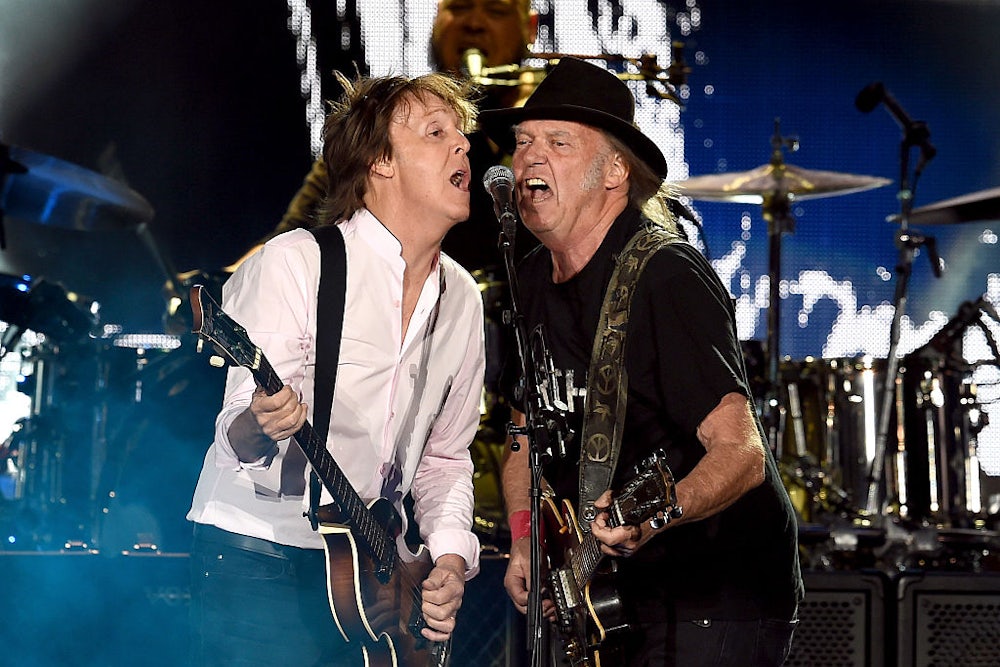

And then there was Desert Trip, derisively and accurately labeled “Oldchella,” the mega-concert featuring Dylan, The Rolling Stones (who incidentally released their first good album in three decades in 2016), Paul McCartney, Roger Waters, The Who, and Neil Young. In one respect, Oldchella was a fitting jewel in the crown of 2016: a testament to rock’s decaying influence.

Rock music has not been this irrelevant since the late 1950s and early 1960s, when its momentum was stalled by Elvis joining the Army, Buddy Holly crashing into an Iowa cornfield, and Chuck Berry being sent to prison for violating the Mann Act. Very little can be said for Don MacLean’s saccharine and embarrassing “American Pie,” a song which persists entirely because baby boomers are especially prone to a particularly smug version of nostalgia. Rock came back from the dead once before, when it was brought back to life by four young men from Liverpool. But this time it looks like it may be gone for good.