Ian Millhiser of ThinkProgress and political scientist Brendan Nyhan recently had a fascinating discussion on Twitter—a phrase I don’t often use—about the condition of American democracy (not good, all agreed) and what that meant for the next time Democrats gained control of both Congress and the White House. Even with a unified government, anti-democratic features in the American system, including a Supreme Court that leans right thanks to a stolen seat, will make genuine progress difficult to impossible. So what should Democrats do? The discussion essentially concerned what the legal scholar Mark Tushnet labeled “constitutional hardball”: that is, the use of legal but non-normative means to pursue positive ends. When it comes to the Supreme Court, Millhiser wrote, Democrats “may need to make some very difficult choices”, including whether to pack the Court.

While the judiciary in America has accrued a substantial amount of power, this power is much more fragile than is commonly assumed. Article III of the Constitution gives Congress the power to establish (or not) lower courts as it sees fit, and also to expand the size of the Supreme Court. Congress can also make “exceptions” and “regulations” to the appellate jurisdiction of the courts. These potentially powerful tools make the judiciary vulnerable to constitutional hardball.

Why has judicial power paradoxically thrived given the weapons that Congress can theoretically use to cut it down to size? Quite simply, because political élites generally favor it. This shouldn’t be all that surprising. Supreme Court justices, after all, are nominated by presidents and confirmed by Senate majorities, and despite the myth of the courts as a “counter-majoritarian institution,” the Supreme Court is rarely far outside the political mainstream. In some cases, like the conservative courts of the Gilded Age or the Warren Court at the height of liberalism under LBJ, the courts are active partners of a dominant national governing coalition.

Since early in the Nixon administration, the median vote on the Court has been a moderate Republican, such as Lewis Powell, Sandra Day O’Connor, and now Anthony Kennedy. These courts have generally been conservative, but deliver enough victories to both sides to maintain elite and popular support for the institution. Indeed, in part because liberal victories under the Roberts Court have been fewer but tend to be higher-profile (most notably on same-sex marriage, abortion rights, and two cases involving the Affordable Care Act), the Court is actually more popular among liberals than conservatives.

But it’s crucial to remember that this equilibrium is contingent, not inevitable. Republicans during Reconstruction manipulated the size of the Court, briefly adding a tenth member, and while FDR’s initial Court-packing proposal—which was presented in an uncharacteristically ham-handed manner—failed, the constitutional crisis that compelled it quickly faded as Justice Owen Roberts started voting with the Court’s liberals to uphold New Deal programs. Soon after, retirements allowed FDR to make enough nominees to ensure a Court that would not interfere with the core New Deal agenda.

It would be very wrong, however, to assume that the overwhelming Democratic majorities in Congress would have continued to do nothing had the Court kept striking down critical New Deal programs. Had the Court refused to back down in 1937, it very likely would have resulted in some combination of Court-packing and jurisdiction-stripping.

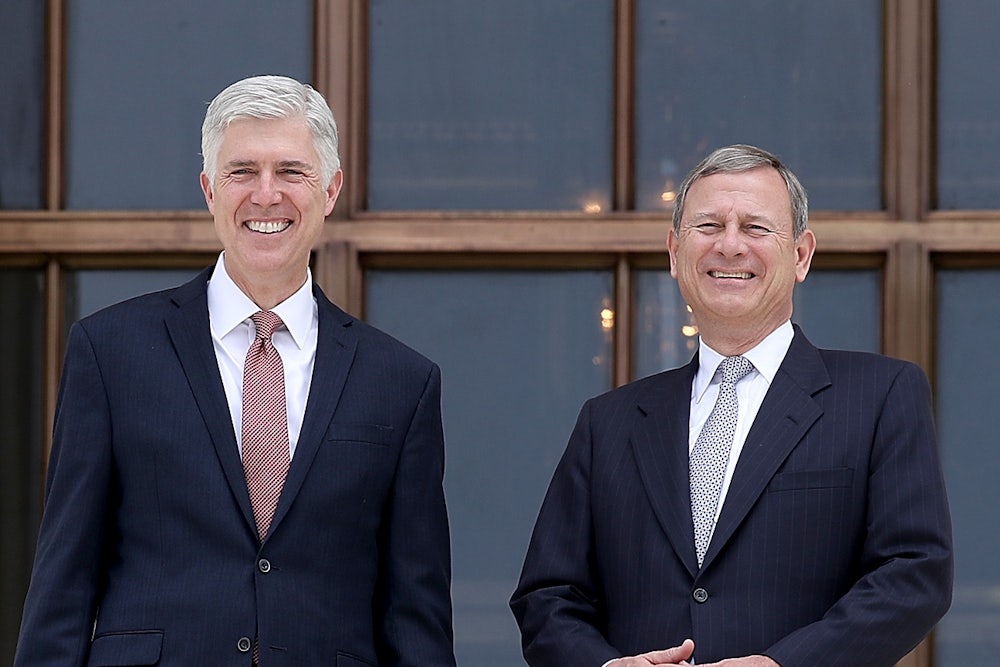

Our contemporary elite polarization means that the center-right Courts of the last four decades will be a thing of the past as soon as Justice Kennedy leaves: The median vote of the Court will be either a conservative like John Roberts or Sam Alito, or a liberal in the mold of Elena Kagan or Ruth Bader Ginsburg. That the Court will be strongly aligned with one political faction during a time of close partisan competition is tinder that could easily fuel a constitutional crisis.

As Nyhan argued, drastic steps like Court-packing carry real costs and should not be undertaken lightly. A Democratic Congress adding two seats to the Court would not be the end of the story, but the beginning of an escalating cycle of constitutional hardball in which the size of the Court is manipulated through both Court-packing and the refusal of the Senate to confirm nominees to fill vacancies during time of divided government. As Millhiser acknowledged, “packing the Court would effectively destroy the legitimacy of the federal judiciary and potentially embolden right states license to ignore decisions they don’t like. No more Roe. No more Obergefell. No more Fourth Amendment.” All things being equal, the nine-member Court equilibrium is preferable to tit-for-tat attacks on the judiciary.

If the Democrats take over Congress and the White House in 2021 with Anthony Kennedy as the median justice—giving them a realistic chance of replacing him—it would be wise for Democrats to hold their fire, barring the Supreme Court serially striking down major legislation on specious constitutional grounds (which the decisions of the Obama era suggest is unlikely).

But what if Donald Trump is able to replace Kennedy, and, God forbid, justices Stephen Breyer and/or Ginsburg as well? There is no good outcome in this scenario. Republicans would have a hammerlock on a nine-member Court for decades. If Trump gets two nominees, this Court is likely to be well to the right of the current Roberts Court and likely to go to war with a Democratic Congress.

Even worse, the decisive nominations would be a product of a Republican Senate refusing to allow a president who won two majorities to fill a vacancy, and then confirming multiple nominees of a president who lost the popular vote by a substantial margin. Court-packing is bad, but allowing an entrenched majority on the Supreme Court to represent a minority party that refuses to let Democratic governments govern would not be acceptable or democratically legitimate, either.

For this reason, it would be very unwise for Democrats to rule anything out. They should be careful not to blow up the power of judicial review without good cause. But if desperate Republicans try to establish an anti-Democratic rearguard on the Supreme Court before they get swept out of office, Democrats have to leave all options on the table.