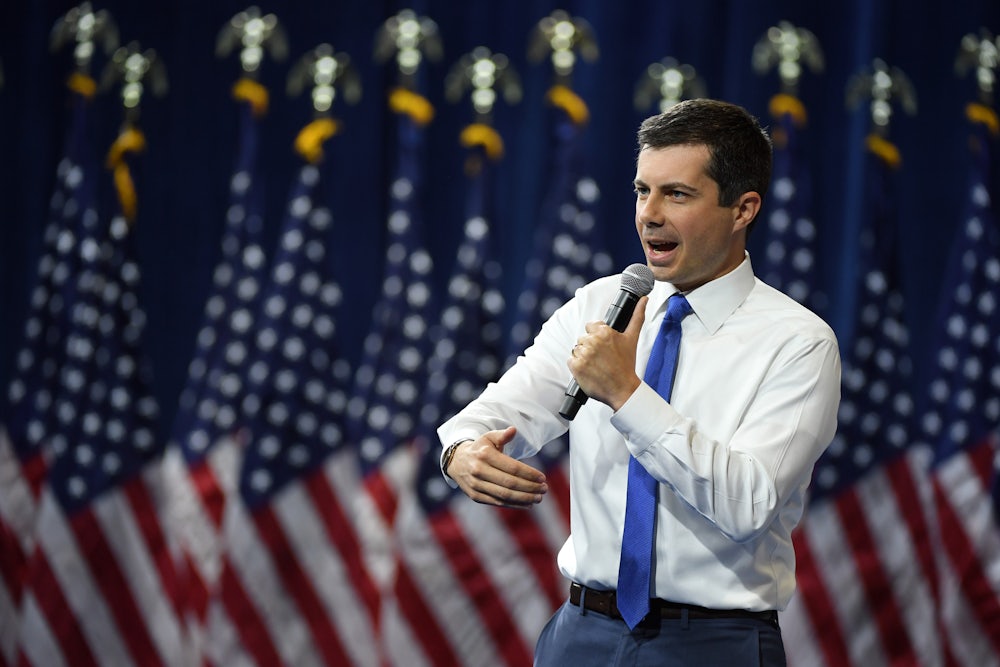

It was November in Iowa, and Pete Buttigieg was having a moment, rising in polls and talking—not quite obliquely—about his military service. “I don’t have to throw myself a military parade to see what a convoy looks like,” the 38-year-old said in his marquee speech at the Des Moines party fundraiser late last year, “because I was driving one around Afghanistan right about the time this president was taping season seven of The Celebrity Apprentice.”

Cathartic barbs at Donald Trump aside, Buttigieg’s military career—he served eight years as a Navy Reserve intelligence officer, including about six months on active duty in Afghanistan—has long played a powerful role in boosting his presidential aspirations. In speeches, debates, policy plans, and campaign stops, Buttigieg suggests that among all the Democratic primary candidates, he best understands the complexities of conflict, the urgent need for peace, and the plight of veterans. In early January, amid escalating tensions with Iran and stagnant poll numbers, The New York Times reported that Mayor Pete would make his military service even more central to his pitch.

Some signs of the pivot were subtle, like Buttigieg changing his Twitter bio to lead with “Afghanistan veteran.” The navigation-menu icon on Buttigieg’s campaign website is an image of his Navy rank. Iowa campaign volunteers were given “challenge coins,” collectible memorabilia popular among certain kinds of military commanders and enthusiasts, to leave at the doors of potential recruits. The campaign named its Iowa blitz “Phase 3,” a get-out-the-vote effort that sounded more like a bust-down-the-door mission. (In military parlance, a “Phase III Operation” is one in which you finally “dominate” the enemy.)

The latest signifier of Buttigieg’s military background came in his caucus-night speech and tweets in Iowa on Monday, when he prematurely declared mission accomplished: “We are going on to New Hampshire victorious,” he said, in the absence of evidence to support the claim. (The Associated Press had still not declared a winner by late Monday.)

Should he secure the Democratic nomination and defeat Trump, Buttigieg would become the party’s first veteran to inhabit the Oval Office since Jimmy Carter, a Naval Academy graduate and former submarine officer. Twenty-six of America’s 45 presidents served in the military. In his quest to become the twenty-seventh, Buttigieg is betting that his experience “outside the wire” and his keen understanding of dynamics in the Middle East will convince voters he’s right for the job of commander in chief.

Much of the veteran wing of the Democratic Party—to the extent that it exists—is lining up in support of Buttigieg. The campaign claims that 4,300 veterans and military community members are officially on Team Pete, and his website today features short, self-taped testimonials from 14 of them. Buttigieg has also earned endorsements from a number of veteran lawmakers, including Patrick Murphy, the first Iraq War veteran to serve in Congress.

In December, VoteVets, a well-heeled political group loosely tied to the Democratic Party, followed suit. According to Federal Election Commission reports, VoteVets has invested more than $1.4 million in Buttigieg this year alone. (In an apparent attempt to skirt campaign rules that bar candidates from coordinating with PACs, a Buttgieg adviser recently appeared to tweet out a thinly veiled request for VoteVets to ramp up such support in Nevada.)

Paul Rieckhoff, the founder of Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America, called the mayor an “inspiration” who is “redefining what it means to be a veteran” in a recent podcast interview. “You’re smart. You’re thoughtful, you’re a well-educated person,” Rieckhoff told Buttigieg. “You’re not just shooting guns, blowing stuff up, and throwing punches.”

Over the years, Rieckhoff has touted his vision of a “camouflage wave” of veteran candidates across the political spectrum who can leverage their service into electoral wins and real reform in Washington. It’s predicated on a piece of conventional wisdom that military credentials make a politician more “electable.” The problem, for Democrats at least, is that this wave has never actually crashed. And while there are some new promising signs of veteran political organizing on the left, party sclerosis is handicapping this work.

While the Democratic Party has run scores of veteran candidates since the Forever Wars began, most of them have lost. The last time the party effectively organized veterans as voters, activists, and campaign volunteers was during Vietnam veteran John Kerry’s 2004 presidential run, as public opposition to the Iraq War spiked.

Under the group banner of “Veterans for Kerry,” four campaign staffers organized meetings at Veterans of Foreign Wars posts and built a massive contact list of veteran voters. Every time Kerry’s campaign plane landed for a rally, staff ensured that a group of veterans greeted him on the tarmac. Yet Kerry voted for the Iraq invasion and stood by his vote throughout the campaign. He was also swiftboated—targeted as an unfit sailor by soft-money attack ads and conservative media narratives that painted his service as a negative. In the end, Kerry forfeited the veteran vote to Bush, 56 percent to 38 percent.

Even in the historic blue wave of 2006, amid public discontent with the war in Iraq, only five of the party’s much-ballyhooed 49 veteran “Fighting Dems” won their congressional races. During the 2018 midterm elections, the Democrats and VoteVets redeployed a Fighting Dems strategy, yet in a strong election for the party, out of the 38 one-on-one matchups run by Democratic veterans, again, only five won. As it turns out, “there is no systematic advantage for veterans on Election Day,” according to political scientist Jeremy Teigen: A candidate’s military service turns out to matter a lot less than incumbency, ad buys, and gerrymandering.

The Dems’ record might be stronger if they had forged deep connections with veteran communities: These voters are civic-minded, politically independent, and largely concentrated in swing states. Many of them are working-class Americans who enlisted in the military for economic and educational advancement.

Knowing this, Republicans have built a mammoth organizing machine aimed at veterans. In 2016, the party hired 50 staffers dedicated to military-community organizing, collected copious amounts of data about veterans and military families, and had fellow veterans knock on more than a million doors. The Democratic National Committee, meanwhile, had just one part-time staffer focused on veterans’ policy issues but no infrastructure in place to identify or organize vets.

The GOP’s investment was matched with supplemental support from the Koch-backed group Concerned Veterans for America. Together, they were able to elevate Trump—a draft-avoiding, Gold Star-family-insulting, real estate tycoon—to the Oval Office, despite evidence that Trump had also reneged on promises of funding to veteran charities. Trump’s 2016 support among veterans was not just impressive; it was historic, nearly triple that of decorated Vietnam War veteran John McCain in 2008. Exit polls showed that veteran support was crucial to Trump’s victories in three decisive swing states: Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin.

There are signs that the left is taking veteran organizing more seriously. Buttigieg, Bernie Sanders, and Elizabeth Warren have each launched veteran outreach programs, a trend that’s virtually unprecedented for a Democratic primary campaign. (Joe Biden has launched a veteran program, but a press inquiry into its machinery went unanswered.)

An emerging class of veteran activists is plotting ground games in swing states with high veteran populations. Its leaders argue that it’s not a candidate’s military service or endorsements from generals that veterans care about but instead more basic issues around labor, the economy, and public corruption. Taking a page from the conservative playbook, these organizers are prioritizing veterans as canvassers, as their vaunted status adds an important layer of credibility to undecided voters. The campaigns are also instituting new and interesting tools to entice veterans. The Warren campaign, for instance, is working to import out-of-state veterans to door-knock in neighborhoods near South Carolina military bases. The Sanders campaign has enlisted veteran supporters to write op-eds in their local newspapers and organize house parties.

“Veteran organizing of this scale has never really been done before on the left,” said Dennis White, a veteran and the leader of Sanders’s outreach efforts. “The right has already spent millions on it. Now we have to do the work.”

The work is complicated by a long history of neglect in the Democratic Party. According to two DNC sources, the party is unprepared to organize veterans for 2020. One bright piece of news, they say, is that the DNC’s veteran and military families council has finally been given a single part-time staffer. Yet there are no reported resources being spent to organize veterans or even identify them. A chief task of campaigns now is to build a list of veteran voters. A veteran staffer currently working for a Democratic front-runner said data provided by the party is essentially useless, as it dates back to Kerry’s run. “We’ve been trying to cull deceased voters from the list but as a result have not been doing the work necessary to identify my generation of veterans,” the staffer said.

Had the party maintained a focus on grassroots veteran organizing after 2004, it could have maintained a potentially game-changing voter database. There was also potential to build up a healthy ecosystem of anti-war veteran activists. Out of the Kerry campaign came a platoon of promising veteran politicos, including Rieckhoff, Murphy, and Jon Soltz, who co-founded VoteVets.

By the mid-2000s, Rieckhoff and Soltz had solidified their standing as the center-left’s veterans of choice. Yet like Kerry, neither veteran spoke out in clear opposition to the Iraq War (nor did their groups) until 2007. As a Kerry proxy in 2004, Rieckhoff gave a national Democratic radio address threading the party’s tiny Iraq needle: “It’s going to take time to reestablish this entire government, this entire country, but I think it has enormous potential, and I think the sky’s the limit for the people of Iraq.” VoteVets, meanwhile, criticized only the “execution of the war” and self-identified as a “pro-military” organization “dedicated to the destruction of terror networks around the world.”

The only overt political anti-warriors at this time were Iraq Veterans Against the War. The group’s activism, laced with rage and resentment at the lies that justified the invasion, had mixed success, but it was searing. IVAW’s most impactful work was Winter Soldier, an event at which more than 200 veterans, soldiers, scholars, and Iraq and Afghanistan civilians spoke on the horrors of war. This activism, messy as it was, helped fundamentally change public perceptions of Iraq. In 2008, Barack Obama prevailed with veterans under 60, largely on the promise of ending wars abroad. Yet a veteran who worked on the 2008 campaign said this support came largely through this promise alone, not because of a successful organizing effort. “The community attached themselves to Obama, it was never Obama’s people going into the community,” he said.

This tenuous relationship with veterans began to crumble when Obama went back on his word, in February 2009, and launched a surge of 17,000 troops to Afghanistan. During the 2012 Democratic National Convention in Denver, at a veterans’ organizing session, delegates openly worried that the party wasn’t doing enough to reach key veteran communities.* (In another embarrassing convention incident, the DNC played a tribute video to veterans that inadvertently displayed warships from the Russian Navy.)

While IVAW is now defunct, a number of its alumni now work at Common Defense, a progressive, fundamentally anti-war veterans’ group that prioritizes grassroots organization. The veteran staffers now working for Sanders and Warren went through the group’s organizing institute. Common Defense may be most famous for bird-dogging conservative lawmakers with questions on camera; a number of these encounters have gone viral.

More consequentially, Common Defense is setting up on-the-ground campaigns in at least three states: Arizona, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. Staffers say they are also cultivating relationships with military veterans in two constituencies where vets are heavily represented–labor unions and the Native American population.

Two labor unions–the AFL-CIO and the Communication Workers of America–have also recently launched veterans’ councils. Forward Majority, another liberal group focused on state races, has recently launched a veterans’ field program in Arizona.

The underlying ethos seems to be to found a movement, not prop a candidate. “The majority of American veterans are working class, diverse, heavily located in key swing states and districts, and among the most trusted and persuasive organizers, canvassers, and leaders within our communities,” Common Defense says on its website. “It’s time we take back our power and speak for ourselves.”

Still, as the 2020 general election closes in, Trump continues to poll strongly among veterans and active duty personnel, and many Democrats are betting that Buttigieg can cut into that advantage. So far, his campaign’s connection to the veteran community feels more Astroturf than boots-on-the-ground. VoteVets lacks a grassroots base and is not known for its organizing prowess. It is instead seen as a dark-money group that makes and places patriotic political ads. The organization’s recent supporters include General Dynamics, Pfizer, and Cigna; its top publicly reported donor is Brian Sheth, a vulture capitalist who once worked in leveraged buyouts at Bain Capital.

There are policy challenges, too: Although Obama’s vet outreach was built on opposition to Iraq, and current veteran opinion against America’s wars tracks pretty closely with high civilian disapproval rates, Buttigieg’s foreign policy views remain more hawkish than those of most of his primary counterparts. He has repeatedly pledged to bring peace to the Middle East, but unlike five of his opponents, has refused to sign Common Defense’s “End the Forever War pledge.” Last week, Buttigieg declined to answer a series of fundamental questions posed by The New York Times on how he envisions a future in Afghanistan.

Even so, a Democratic war veteran is inoculated against Republican charges of weakness, right? If anything, that’s even less true in the age of Trump than it was in 2004. In a recent interview with the Times, Seth Moulton, the Democratic Massachusetts congressman and brief former presidential candidate who served four combat tours in Iraq, summed up the likeliest line against Buttigieg’s naval intelligence career in a general election: “There’s no combat veterans left in the race,” he said.

“I have tremendous respect for Pete’s service as an analyst,” Moulton said. “But analysts don’t make decisions.”

* This passage was updated to remove a reference to an event that occurred at the 2008 convention.