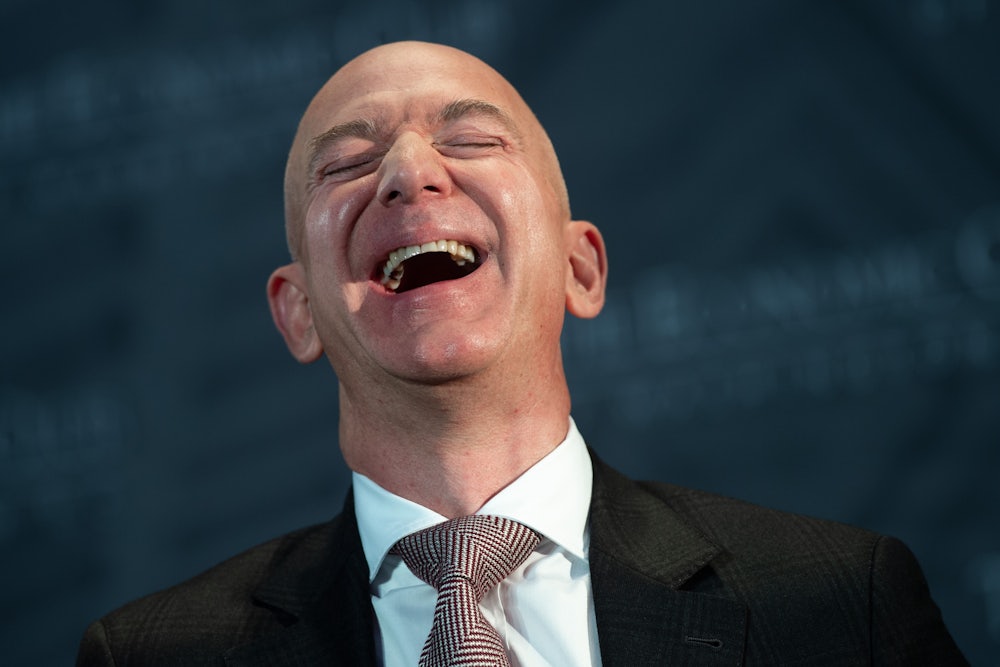

On Tuesday, as Amazon announced record earnings amid the pandemic, CEO Jeff Bezos said that he would be stepping down from his position, passing the torch to Andy Jassy, who leads Amazon Web Services, the massively successful cloud computing and digital infrastructure division. Bezos will become the company’s executive chairman (until now, he has also held the titles of president and chairman of the board) and devote himself to his various other interests, including his rocket company, The Washington Post, and climate philanthropy.

For Bezos, the transition makes sense. As rich as a pharaoh, Bezos oversees a range of investments and dilettantish projects, and now he can do absolutely whatever he wants, while serving as a figurehead of perhaps the most important company in the world. But more than one oligarch’s passage into the next chapter of his life, the executive shuffle at Amazon merely affirms how massive and powerful the company has become—a self-sustaining behemoth that, no matter who’s at the helm, will continue devouring industry after industry with no end in sight. Bezos’s move also suggests that the window to tame this rapacious monster may be rapidly closing.

The fact that Amazon no longer needs its insatiable founder is cause for worry, not relief. The sprawling company can continue dominating online retail, copying popular products, underpaying its workers, obstructing unionization campaigns, and helping fossil fuel companies extract more climate-altering hydrocarbons—all while making enormous profits and building toward a $2 trillion market cap. The inherent contradiction of Amazon is that it’s both a colossally harmful enterprise—to labor and the environment especially—but also an essential part of consumer ecosystems ranging from retail to logistics to streaming video. The ethically minded consumer’s challenge, increasingly, is to find a way to live without it—the definition of a monopoly, if there ever was one.

On the same day that Bezos announced his move, news broke that Amazon will pay $61.7 million to drivers for withholding their tips—essentially, for stealing their wages. Amazon is also engaging in a campaign to discourage unionization at a fulfillment center in Alabama, a labor struggle that could have wide repercussions for the company and its immiserated army of warehouse workers and drivers. For any normal firm, these might be cause for a public relations blitz or, indeed, an executive turnover, but these are barely blips on the Amazon radar. The company’s canny P.R. strategy has been not to engage its critics, to shrug off tales of scandal and exploitation with silence or anodyne statements. In this way, it’s been able to survive public scrutiny and cement its place as a company that, while more politically aware shoppers might feel squeamish buying from it, is all the same too convenient (and its prices too low) to resist.

The next few years are pivotal for Amazon. As much as Donald Trump despised Bezos and his ownership of The Washington Post, President Biden is far more likely to countenance antitrust or other regulatory action. At the very least, a spin-off of Amazon Web Services—the company’s most profitable division and a key provider of internet infrastructure for anything from Netflix to the CIA—would make sense. (Given its monopoly status, Amazon should be nationalized, but that possibility sits well outside the Overton window.) Amazon is clearly aware of the threat: It spent more than $18 million on political lobbying in 2020. And while it failed to procure a much-desired Defense Department contract for cloud computing—that went to Microsoft, a decision Amazon protested as corrupt—it still wields tremendous, and profitable, influence. Last year, for instance, the General Services Administration introduced a program that allowed government agencies to purchase products and supplies through Amazon, opening a lucrative new revenue stream.

Unshackled from his daily corporate duties, Bezos can act as a roving representative of Amazon’s interests, meeting with politicos and regulators and making the case that Amazon, as constituted, is essential to the U.S. and global economies. More influential than any lobbyist, and with the celebrity afforded to one of the world’s richest men, he will become a ubiquitous quasi-statesman figure in the mold of Bill Gates—pressing the flesh with a king here, sponsoring a climate initiative there, promising that his rocketry company will help save the planet. (And as with Gates, Bezos’s fortune is likely only to increase, even as he dumps more of it into philanthropic efforts.)

Bezos is fond of saying, as he did in his goodbye letter to employees, that it is always Day 1 at Amazon, a reflection of the company’s relentless culture. But a company always stuck on Day 1 is unlikely to think beyond the demands of the present—or about what kind of harmful power it might wield. Such a company doesn’t care about what it has done already, only what it might do. The current dangers of Amazon—to labor, the environment, small businesses, and minimum-wage workers—are all too clear. What’s more disturbing is the culture that Bezos has built, namely an unaccountable Goliath that can seemingly do no wrong on the way to invention, profits, and a global influence we’re only beginning to comprehend.