“The great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us … history is literally present in all that we do.”—James Baldwin, 1965

In the weeks since the storming of the U.S. Capitol by a lie-emboldened mob of Trump-branded insurrectionists, many political leaders and mainstream pundits across the political spectrum have assiduously sought to displace white supremacy’s starring role in the attack. On the far right, those who stormed the Capitol to “Make America Great Again” understood themselves to be patriots—asserting their standing as supercitizens, unbound by either election results or civil legal restraints, thanks to their privileged relation to American politics as a white propertied project.

In response, hand-wringing moderate commentators reached for their well-worn “this is not who we are” response. Their plea to conjure up the better angels of American memory amounted to a séance for the countless lives lost in the overthrow of Reconstruction’s multiracial democracy. Meanwhile, left pundits debated the “are we there yet?” question by looking to European history to find out whether January 6 signaled the onset of fascist decline. Neatly sidestepping the centuries-long reign of white supremacy in America that fed and sustained distinctly fascist currents in our politics long before Kristallnacht and long after the fall of the Third Reich, they inadvertently revived the same amnesiac refrain that prompted Langston Hughes to note, in 1937, “We Negroes in America do not have to be told what fascism is in action. We know. Its theories of Nordic supremacy and economic suppression have long been realities to us.”

Indeed, each story line on the Capitol insurgency—particularly from the left and center—reflects a great deal of bowdlerized history, especially when it comes to the enduring legacies of American racial terror. This denialism bespeaks a broader failure to face up to the real nature of white supremacy across the political spectrum. Even at this late date, our commentariat overwhelmingly treats white supremacy as an over-there topic that warrants cursory interrogation and minimalist intervention—an excusable affliction of prejudice, an ancillary dimension of class power, or the distant echo of a long-ago social order with secondary significance in today’s crisis. Only the far right takes white supremacy onboard directly as its stolen birthright, and even the Confederate flag–wavers in its ranks routinely often deny that the “way of life” it symbolizes was grounded in defending the dehumanization of Black people.

To understand how explicitly anti-democratic desires can be framed as defending freedom, as well as how moderate and left responses to this political violence seem to underestimate its continuity from the past and its threat to our future, we have to grapple with the foundational role of white supremacy in our republic. Indeed, the drafters of our Constitution sanctioned the very notions of security and property as racialized interests hardwired into our political system. As a result, subsequent actions seeking to dismantle this legacy have been framed as illegitimate, preferential, and deeply threatening to the social order. The retraction of entitlements that were once taken for granted within a white supremacist order not only spurs vigilante violence; it also infects the color and code of law enforcement itself.

This racialized construction of law and order explains the jaw-dropping difference in the fully militarized response to Black Lives Matter protests and the collegial escort of the insurrectionists out of the ransacked Capitol. To begin to address this obscene disparity between those who marched to uphold the republic’s ideals and those who spilled blood to overthrow them, we must grapple with the fact that whiteness—not a simplistic racial categorization, but a deeply structured relationship to social coercion and group entitlement—remains a vibrant dimension of power in America.

As Cheryl Harris, David Roediger, and others have argued, property in whiteness has long served as a critical source of sociopolitical status. As a robust ideology, it ties wildly conflicting cross-class interests into a political stranglehold denying any sustainable and actionable sort of racial or socioeconomic equality. The cry of law and order has wrapped this family bond into a repetitive refrain in modern American politics, obscuring the violent ways in which a racialized underclass has been repeatedly disenfranchised and disciplined by the dictates of a white majority. The murderous January 6 insurrection furnished a snapshot of this racialized model of social order that’s long been familiar to America’s racialized others. Under this hermetic system of repression, white disorder simply does not compute as an existential threat to the republic. Even though the nation was nearly destroyed by the treasonous explosion of white rage in the Civil War, the would-be cautionary tale about the mortal threat of a fully weaponized supremacist agenda has largely remained, in the words of President Woodrow Wilson, a “quarrel forgotten.”

Thanks to the privileges and immunities of whiteness, those who have credibly questioned its hold—dreamers like Martin Luther King Jr., Fred Hampton, and Malcolm X—were targeted, surveilled, and martyred before they reached the age of 40, while white supremacist agitators and murderers lived long lives as their suit-and-tie enablers brokered power in an unrepentant republic. To this day, racial justice advocacy comes with risks that few white nationalists will ever know—even those who kill. Kyle Rittenhouse has largely resumed his life; protesters from Ferguson to D.C. who took no one’s life have been arrested, dragged through the legal system, and even killed.

At the center of this twisted notion of law and order is the nation’s hagiographic self-narrative of being “born perfect and improving ever since.” Dominant in popular and political culture, this ideological mythmaking was scaffolded into political discourse over a century ago by the likes of the filmmaker D.W. Griffith. Still heralded as the father of American film, Griffith supplied a vigilant defense of the Confederacy’s Lost Cause mythos in The Birth of a Nation, which was purportedly hailed by President Wilson as “like writing history with lightning.” This propaganda offensive has hidden in plain sight in textbooks throughout the twentieth century, and in rituals that celebrate the American nation’s supposedly unbroken commitment to freedom and justice for all—a story that again demands a virtual conspiracy of silence about that ugly little matter called the Civil War.

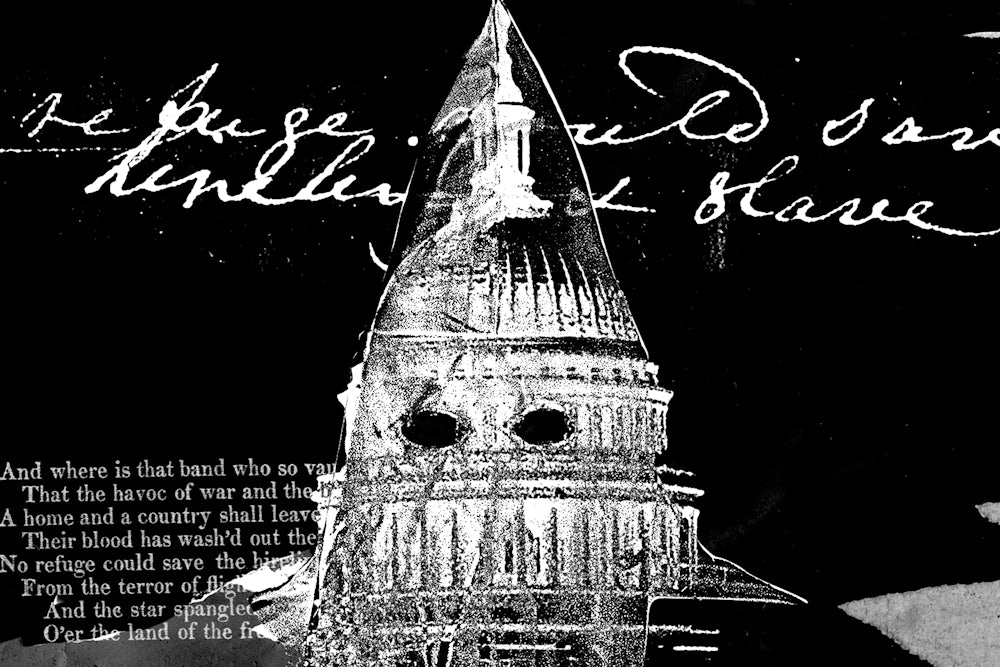

The go-to performance of national unity—the national anthem—works only by forgetting that Francis Scott Key’s ringing homage to “the land of the free and the home of the brave” savagely excluded the Black Americans whom he enslaved. And it was those same Black Americans whom Key’s brother-in-law, Supreme Court Justice Roger Taney, declared in Dred Scott v. Sandford to be so inferior, so debased, that they could never be part of the republic he lauded.

The long-mythologized story of American innocence, white redemption, and moral superiority is fully of a piece with the deification of the Founding Fathers themselves. And as searingly marked by the 1776 Commission’s response to the 1619 Project, any deviation from this beatification invites bitter and immediate reprisal. Today’s backlash against the sacrilegious unearthing of slavery lurking in the shadows of America’s miraculous birth recalls a moment following the celebration of the Constitution’s bicentennial, when the right demanded the resignation of Thurgood Marshall from the Supreme Court. His sin? Reminding the starry-eyed celebrants that the rights they valorized didn’t flow from the flawed 1787 Constitution—the document that recognized and insulated slavery—but from the amended Constitution that emerged from a cataclysmic war and decades of struggle.

A more complete expression of the facts of American history urgently underlines the question of why we’re unable to grasp in full how the founding racial dispensation surrounds and defines virtually every issue in our public life. There’s clearly a deep and ongoing cognitive incapacity to recognize the lethal handiwork of white supremacy. And this repression of national trauma blockades any real reckoning with the racial disparities of the Covid pandemic’s death numbers, the color of our nation’s inmates, or the demographic makeup of our most vulnerable citizens.

The chronic failure to confront the monsters of our past is not destiny; it’s a daily choice to accept American myth in the face of so much countervailing evidence. We are choosing and choosing again to return to a fantasy of our national virtue. Yet our return to that fantasy is what ensures that another moment or another generation will be forced to confront the ugly and overlapping legacies of genocide, slavery, and apartheid. To break this cycle—to imagine ourselves otherwise—we have to take up the failures of the dominant intellectual zeitgeist and ground the American narrative on a different plane.

A critical engagement with race in America means repudiating the fantasies of immaculate conception. It urges us to resist the corresponding desire to simply walk away from the scene of the crime and declare that the many still-thriving legacies of white supremacy are over and done with. By these lights, it’s just class that underwrites resentment. Reckoning with race, on the other hand, means understanding white supremacy as a foundational form of social power.

White disorder tells us something about how our national mythology continues to naturalize and defend immense racial and democratic inequalities. Law, politics, culture, and economic policy should be mobilized to interrupt the toxic expectations grounded in the nation’s foundations and to cease indulging, excusing, and rebranding the white grievances that fuel anti-democratic forces. Indeed, to build a nation that is a better reflection of our expressed ideals, we have to imagine a different baseline from which conceptions of justice and democracy flow—a baseline not beholden to the legacies of genocide and slavery but one of a republic reborn as a multiracial democracy.

Among other things, the second Senate acquittal of Donald Trump stands as another deadly moment in which we the nation turned away and shrugged before the specter of a racialized effort to overthrow our representative democracy. As a result, the heartbeat of white supremacy endures and gives life to new and brutal forms of repression and denial. Even though the Capitol uprising afforded a telling glimpse of its fascist visage, this homegrown monster can still claim salvation through bipartisan deliverance. As its staunchest defenders pretend it doesn’t exist, it eludes apprehension from those who have convinced themselves that the utter destruction that white supremacy enables couldn’t quite happen here—even though it already has.