The following is an excerpt from Astra Taylor’s new book, Remake the World.

“It’s as natural as breathing” is a cliché because, when all is going well, nothing else is more effortless than inhaling and exhaling, something we do approximately twenty thousand times a day. Typically, most of us don’t think much about it. We breathe as we sleep, breathe as we eat, breathe as we move, and breathe as we talk. But that changed in 2020. We worried about our lungs and gasped for air. A novel illness sickened millions and tanked the global economy, thousands ingested tear gas protesting police violence, and cities were smothered by plumes of dark, noxious smoke from nearby forest fires.

During the first tense few weeks of the Covid-19 shutdown, we thought we could stop the spread of the disease by washing our hands. Our hands were something we could control. We could keep them in our pockets, wear latex gloves, have sanitizer at the ready, and scrub off the pathogen with soap and hot water. We didn’t have all the facts. The coronavirus, as U.S. authorities knew by early February, is airborne, transmitted through invisible particles and droplets emitted and ingested during the most automatic of physical acts. The pandemic has revealed “that our bodies function more like sponges than fortresses,” my sister, the disability rights activist and scholar Sunaura Taylor, observed. “In a variety of visualizations, we see our bodies extending beyond their usual bounds: graphics of our coughs, sneezes, and even breath show how far beyond our own skin our bodies reach; the six-foot rule of social distancing a daily acknowledgment that our bodies not only leak and ooze, but that they absorb the conditions of others.” Epidemiology and physics colluded to prove that even at a seemingly safe distance, we touch by virtue of breathing the same air.

In the worst cases, Covid-19 causes acute respiratory distress. Experts describe succumbing to the disease as akin to drowning. Early in the outbreak I read a piece by a doctor attempting to educate readers about how our lungs operate and what contracting the illness might entail. A healthy lung is so soft, she wrote, it “has almost no substance”; touching it feels like “reaching into a bowl of whipped cream.” Covid changes that, filling the twin organs with a yellow goo that blocks the free flow of oxygen: “The lung texture changes, beginning to feel more like a marshmallow than whipped cream.” To be soft and permeable like a sponge is to be healthy. To be rigid and closed off, fortresslike, spells doom. This is true, it turns out, not just for our lungs but also for our very selves.

When we breathe, we pull air into our windpipe, or trachea. That pipe than splits into our lungs’ two main airways, called bronchi, which then branch off into smaller and smaller passageways, leading to tiny twig-like tubes called bronchioles that culminate in clusters of microscopic sacs called alveoli. In medical diagrams these passageways resemble the branches of an upside-down tree, as though every human being contains a piece of an inverted forest inside their chest. It’s a fitting image, because if it weren’t for trees, we wouldn’t be able to breathe. By photosynthesizing, plants generate carbohydrates and oxygen in equal measure, nourishing our bellies and filling our lungs. Without them we’d starve, but not before we choked on lethal levels of carbon dioxide. In this sense, the thousands of fires that raged across North America in 2020, burning more than eight million acres, charred the lungs of the earth.

In those months, some communities gagged on smoke, others on pepper spray. On May 25, forty-six-year-old George Floyd was asphyxiated by Derek Chauvin, a Minneapolis police offer who kneeled on Floyd’s neck for eight minutes and forty-six seconds with an expression of untouchable, detached superiority. Floyd’s alleged transgression was using a counterfeit twenty-dollar bill. The assault was caught on video, and perhaps because the pandemic had slowed things down, people paid attention. Floyd’s murder galvanized the biggest protest movement in U.S. history, attracting up to twenty-six million participants by midsummer. Police and federal agents responded with unrelenting force, blinding over a dozen eyes with rubber bullets and burning thousands of people’s lungs with chemical weapons, including smoke grenades. In Portland, Oregon, residents used leaf blowers for self-defense, redirecting fumes away from innocent crowds and back toward the cops. Floyd’s last words echoed Eric Garner, who uttered a phrase that would become a common chant at Black Lives Matter protests as he was killed by police in New York City in 2014: “I can’t breathe.” In streets full of tear gas, demonstrators couldn’t breathe either.

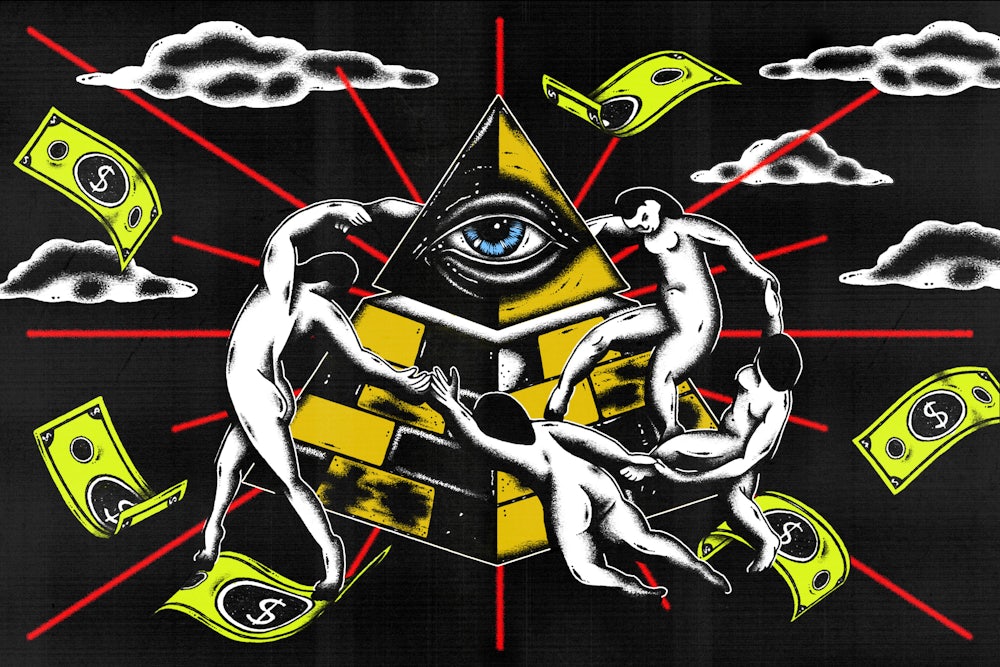

The right wing, predictably, responded to these developments with aggressive denial. Millions of people already devoted to conspiracy theories merely had to add a few new twists to preexisting narratives to bring them up to date. The coronavirus, like global warming, was a hoax, an elaborate ruse by an elite and evil cabal to control the populace—not a pandemic but a “plandemic.” Likewise, the fires in California and Washington were not connected to shifting weather patterns caused by greenhouse gas emissions, but the result of arson, violent acts committed by mythic anarchists and anti-fascists who were never found but who were certainly in cahoots with Black Lives Matter. From his White House perch, Donald Trump amplified falsehoods, uplifted racists, and sowed confusion and doubt. Research showed he was the single largest source of disinformation about Covid-19. While condemning millions to disease and destitution, Trump told his followers they were victims not of a vastly unequal society (helmed by a sociopathic plutocrat no less) but of public health protocols and marginalized groups seeking equal rights; he comforted those afflicted with delusions that a reassertion of white supremacy and a revolt against a spectral “deep state” could cure the crisis. A network of right-wing individuals and foundations funded and fomented discontent, emboldening armed vigilantes who gathered at state capitols demanding a return to business as usual. In Michigan, fourteen men, aggrieved by coronavirus restrictions, were arrested for plotting to kidnap Governor Gretchen Whitmer. Court documents show they also discussed storming the legislature to “take hostages, execute tyrants, and have it televised.” Instead of being snapped back to their senses by a deadly illness, people retreated further into fantasy and fallacy, in which face masks were part of a far-reaching conspiracy to suffocate patriots and stifle freedom.

According to my dictionary, a conspiracy is “a plotting of evil, unlawful design; a combination of persons for an evil purpose.” This is the definition that describes the most popular conspiracy theories of our day, which claim to ferret out a demonic sect pulling society’s strings, whether they are nefarious globalists, Jewish bankers, a Satanic pedophile ring, a “shadow government,” or some dastardly combination thereof. While such misapprehensions are as old as the nation itself—some historians point out that the United States was born of a conspiracy theory, as evidenced by the Declaration of Independence’s paranoid litany of Britain’s “abuses and usurpations,” including unleashing “merciless Indian savages” and “absolute despotism”—the Trump era was uniquely steeped in them. Trump’s rise to power began with the racist lie of birtherism (insisting that Barack Obama was not a true U.S. citizen) and ended in the authoritarian insistence that the election was rigged and stolen by “socialist” Democrats, with the help of some disloyal Republican officials (among them Attorney General William Barr). While people on the political left are not immune to it, this kind of conspiracism is more endemic among and useful to the right wing.

If we go further back, however, we’ll find the word conspiracy has a different, more profound meaning that might help us comprehend our present predicament. It comes from the Latin conspirationem, “agreement, union, unanimity,” and conspirare, “to be in agreement; to ally”—or, literally, “to breathe together.” That is what the more powerful segment of society, the ruling class, have never wanted the rest of us to do—to come together as allies and, god forbid, form unions. Throughout U.S. history, the most influential and destructive conspiracies have emanated not from the fringes but from the country’s political and financial centers of power, and their goal has been preventing regular people from banding together to improve their lot. Polls reveal shockingly high levels of isolation and loneliness among the U.S. population, conditions that are known to make people more susceptible to the destructive, paranoid conspiracy theories that abet the right wing. We are all living amid the wreckage of a long, ongoing, and intentional sabotage of progressive collective action: a profit-driven health care system ill-prepared to cope with a pandemic, runaway climate change threatening the future, a bigoted and broken criminal justice system, a misinformation-addled (and conspiracy-promoting) corporate media sphere, and an economy in which the majority of people can barely keep their heads above water. Our inability to truly conspire is why so many people are struggling to breathe today.

“The power to define what is and is not a conspiracy is a jealously guarded privilege,” Michael Mark Cohen writes in his fascinating book The Conspiracy of Capital: Law, Violence, and American Popular Radicalism in the Age of Monopoly. In the early days of the United States, this battle would be fought overwhelmingly in the courts.

The first labor conspiracy case in the United States was the Philadelphia Cordwainers trial of 1805 to 1806, and it remains one of the most significant trials in labor history to this day. “A group of journeyman shoemakers attempted to combine to demand higher pay and prevent the hiring of replacement workers,” Cohen explains, and in response they were charged with forming “a combination and conspiracy to raise wages.” Shoemaking was one of the city’s most profitable industries, and it was also the most contentious. A dispute over wages led to a seven-week strike and then a lawsuit, with eight journeymen indicted. A scab testified that the “workers were foreigners seeking to overthrow the laws of the United States” (the trope of the outside agitator was already in effect). The prosecution argued that the workers’ collusion threatened not only the shoemaking industry but also the entire city’s economy. While the workers got off with a small fine, the case set a disturbing precedent. Other courts interpreted the verdict as a ban on labor unions, which meant that organizing efforts were henceforth subject to suppression from both employers and the state. Between 1806 and 1842 there were more than twenty-one labor conspiracy trials involving “cordwainers, tailors, hatters, spinners, and carpet weavers,” Cohen reports. Strikers won six of them. But in each and every case, unions were deemed illegal “combinations” and “conspiracies” and forbidden.

Speaking for countless others, Philadelphia labor leader Stephen Simpson railed against a double standard that tilted the playing field in favor of employers. “If mechanics combine to raise their wages, the laws punish them as conspirators against the good of society, and the dungeon awaits them as it does the robber,” he wrote in 1831. “But the laws have made it a just and meritorious act, that capitalists shall combine to strip the man of labour of his earnings, and reduce him to a dry crust, and a gourd of water.” Robert G. Ingersoll, a famed agnostic and social reformer, would later express the same sentiment in a pithier formulation: “If the rich meet to reduce wages, that’s a conference; if the poor resist the reduction, that’s a conspiracy.” The double standard would be etched into law: At the same times workers were under attack, the owning class was provided with a bevy of new rights. A corporation would be redefined as a “legal person” entitled to equal protection. Limited liability companies received state sanction and support while labor unions were deemed illegal.

As the age of monopoly wore on, conspiracy charges ramped up. The common law doctrine of criminal conspiracy allowed the captains of industry to regulate working-class organization with incessant litigation, turning courtrooms into centers of class conflict. A vague and broad accusation, the conspiracy doctrine implied guilt by association and was used to suppress dissent, “to ban unions, outlaw strikes, pickets, and boycotts, to criminalize radical ideologies like anarchism and communism,” in Cohen’s words. The doctrine was considered “the darling of the prosecutor’s nursery” for its sweeping application and loose evidentiary rules, which meant it was perfect for suppressing dissent—anyone could be sucked into the ring of conspirators, even those who had never met before. “If there are still any citizens interested in protecting human liberty, let them study the conspiracy laws of the United States,” the famed radical lawyer Clarence Darrow, implored. “No one’s liberty is safe.”

Born in 1857, Darrow defended countless workers and organizers from conspiracy charges over his career, inspired, in part, by the famous Haymarket trial, a miscarriage of justice that saw eight anarchists charged with conspiracy and seven sentenced to death for an explosion at a small rally (a pardon would be issued in time to save three of them). In an attempt to mount more successful defenses, Darrow dug into the conspiracy doctrine’s history to uncover its basis in English common law, only to discover that its original purpose had been turned on its head. First codified in 1305, the conspiracy doctrine began as a medieval English law designed to prevent malicious persecution. “It was an ancient law that a man who conspired to use the courts to destroy his fellow-men was guilty of treason to the state,” Darrow concluded. “He had laid his hand upon the State itself; he had touched the bulwark of human liberty.”

The Age of Revolution flipped the script, shifting the doctrine’s purpose from the prevention and punishment of private abuse of the jury system to the subversion of efforts to build working-class solidarity. In 1721, English judges ruled in Rex v. Journeymen Tailors of Cambridge that workers’ efforts to strike to raise wages amounted to an unlawful and criminal conspiracy, setting the stage for the Combination Acts of 1799 and 1800, which made trade unionism illegal in Britain, though laborers continued to put up fierce resistance. “The aristocracy were interested in repressing the Jacobin ‘conspiracies’ of the people,” Cohen explains, while “the manufacturers were interested in defeating their ‘conspiracies to increase wages.’” The Combination Acts did both. A cross section of elites gained power, and labor was forced into the shadows. As a result, the historian E.P. Thompson notes in his study of the English working class, organizing became more furtive, or “conspiratorial” in its modern-day sense. Workers could unite only in secret, ever watchful for employers, magistrates, parsons, and spies who might be their undoing.

Workers fought back, but always from a defensive crouch. In the United States, laborers exploited on the job faced retaliation for demanding better treatment. They could be fired, wounded, or lynched, whether by hired Pinkerton guards or volunteer reactionary mobs. World War I inflamed ethno-nationalist tensions and put targets on the backs of radicals, with thousands arrested and often deported in the infamous Palmer Raids. The wartime Espionage Act strengthened the hand of the state, making it possible to prosecute labor partisans for words alone. The legendary organizer Eugene Debs was jailed for declaring that the only war in which he would enlist “was the war of the workers of the world against the exploiters of the world.” Voicing that sentiment landed him in prison for sedition, a charge held up by a unanimous Supreme Court decision.

With hindsight, we regard the Haymarket affair, the first wave of the Red Scare, and the Palmer Raids as egregious abuses of state power. But rather than being aberrations, they epitomize a troubling current that has coursed through U.S. history since the colonial days, carried across the Atlantic via British common law all the way to the present day—a disastrous determination to squelch the efforts of working people to become organized. “The most dangerous conspiracy theories, especially rightwing conspiracy theories, do not exclusively populate the extremist margins of American politics and history,” Cohen observes. “Rather, the most dangerous conspiracy theories in American politics emerge from the very center of power, in which white supremacist, anticommunist, and anti-terrorist ideologies, each defined by shifting fears of subversive conspiracies, are promoted and enacted by presidents, business leaders, military men, judges, prosecutors, police, and vigilantes.” The most destructive purveyors of conspiracy theories are not average people who anxiously embrace half-truths. Rather, the real threat comes from those who hold official positions of influence and who actively trade in damaging lies to maintain dominance, fully aware that their continued authority depends on the disorientation, distraction, demoralization, and disarray of millions of others. If that sounds conspiratorial, it is. “I think a little conspiratorialism on the left is sometimes healthy. There actually is a cabal of ruling elites that seek to poison and imprison this world in the name of profits,” Cohen told me by email. “And those people have names, addresses and regularly meet to plot their crimes against humanity and nature. We have much to gain by naming and fighting them both individually and as a group.”

In 1961, sociologist Daniel Bell speculated that there is “in the American temper, a feeling that ‘somewhere,’ ‘somebody’ is pulling all the complicated strings to which this jumbled world dances.” The esteemed historian Richard Hofstadter echoed that sentiment, publishing The Paranoid Style in American Politics to great acclaim. Over the course of the Trump presidency, countless op-eds, journalistic exposés, academic articles, and books have articulated a similar concern, citing the explosion of conspiracy theories and the elevation of some of the most outlandish ones to the halls of power. The same election that evicted Trump from the White House secured victory for two congressional candidates who publicly supported QAnon, a convoluted conspiracy devoted to interpreting message board missives from “Q,” a mysterious figure and supposed government insider with knowledge of Trump’s plan to vanquish the Devil-worshipping, child-molesting globalists who currently run the world and send them to Guantánamo Bay with the help of John F. Kennedy Jr., who faked his own death in 1999 and has been in hiding ever since. At the end of 2020, NPR and Ipsos published the results of a poll assessing QAnon’s reach. Seventeen percent of respondents said it was “true” that “a group of Satan-worshipping elites who run a child sex ring are trying to control our politics and media,” and 37 percent more said they didn’t know. Without a doubt, it is alarming when millions of people reject basic reality, even the reality of something as banal as a celebrity’s death. Yet attempts to diagnose the problem’s source and identify possible cures too often fall short.

The book A Lot of People Are Saying, from 2019, epitomizes the genre. Authors Nancy Rosenblum and Russell Muirhead describe what they call the “new conspiracism,” or “conspiracy without theory.” In their schema, classic conspiracism’s evidentiary basis (picture dozens of JFK assassination aficionados poring over photographs of the grassy knoll) has been abandoned in favor of pure affect; hypotheses and suppositions gain purchase through repetition, not proof. Digital networks drown internet users in dubious information designed less to persuade than to overwhelm, as social networks circulate and recirculate sensational claims. Those who know how to game algorithms amass enormous followings, and those with the most “engaging” content always win, accuracy be damned.

In 2020, millions of jobs evaporated overnight, but hucksters hit pay dirt. The clickbait economy launched the careers of an astonishing number of “conspiracy entrepreneurs,” a handful of whom, like Alex Jones, are national figures while the vast majority carve out a specialized niche, perhaps exposing “crisis actors” (the people who purportedly pretend to be victims of mass shootings as part of a larger plot to undermine the Second Amendment) or tracking “chem trails” (mind-controlling vapors allegedly released by planes). Rosenblum and Muirhead quote Stefanie MacWilliams, a twentysomething woman from Belleville, Ontario, who gained notoriety for propagating the myth of “Pizzagate,” which held that prominent Democratic political operatives (including Hillary Clinton and John Podesta) ran a pedophile ring housed at a popular pizza parlor in Washington, D.C., called Comet Ping Pong, which inspired a man to travel from North Carolina, enter the premises, and fire a military assault rifle, demanding the release of imaginary sex slaves he believed were being held in a nonexistent basement. Despite the fact that someone could have been killed during the commotion, MacWilliams was unremorseful: “I really have no regrets and it’s honestly really grown our audience.”

A Lot of People Are Saying maintains that while conspiracism has long pervaded U.S. politics, something significant has changed in recent years. “Today, conspiracism is not, as we might expect, the last resort of permanent political losers, but the first resort of winners,” the authors observe, in a reference to Donald Trump’s rule as conspiracist-in-chief and the Republican Party’s tendency to paint itself as a victim even as it wields political power. For all the authors’ supposed historical acuity, their insistence that conspiracy theories originating from the powerful is a new phenomenon only holds if you selectively interpret and idealize the past. A cursory glance at U.S. history, or a close read of Michael Mark Cohen, shows that the powerful have claimed to be victims since the founding of the nation. The lies peddled by Trump and the Grand Old Party are just the latest iterations of the truth-destroying, state-building ideologies of yore.

Today we use the term Red Scare to indicate an overreaction, but the mania lasted the better part of the twentieth century, peaking twice, first around World War I and then after World War II. During the second surge, the House Un-American Activities Committee, or HUAC, devoted incredible energy to pinpointing communist influence in government and industry, an influence that zealots detected in New Deal social programs, strong labor protections and trade union militancy, and the civil rights movement, which Representative John Rankin of Mississippi denounced as “communistic bunk.” Operating in a similar vein, Senator Joseph McCarthy launched a crusade in Congress, seeking out subversive elements in Washington and Hollywood. His efforts lost steam only when they were broadcast on national television and public opinion turned against his inquisition (an unforeseen reaction that sparked the first denunciations of the “liberal media”). But of course, the conspiracism didn’t stop with the end of the demented government hearings. Under the fervid anticommunist leadership of J. Edgar Hoover, the Federal Bureau of Investigation continued to spy on citizens, including via COINTELPRO, a counterintelligence program designed to surveil, infiltrate, discredit, and disrupt left-wing groups. As one official memo put it, the aim was to “enhance the paranoia endemic in [dissident] circles” and convince activists that FBI agents lurked “behind every mailbox.” A letter sent by the program tried to pressure Martin Luther King Jr. to kill himself. The CIA abetted the cause with Operation CHAOS, initiated by President Lyndon Johnson in 1967 and expanded by Richard Nixon, which “infiltrated antiwar groups, black power organizations, and even women’s consciousness raising sessions to determine if foreign communists were secretly directing them.”

As Kathryn Olmsted documents in her illuminating book Real Enemies, U.S. citizens are suspicious of their government for good reason. Government lies have cost livelihoods and lives. In 1962, the Joint Chiefs of Staff presented Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara with a plan to deceive Americans into supporting a war on Cuba by launching self-inflicted terror attacks on U.S. soil. While that idea was scuttled, U.S. policies of deception and secrecy were par for the course in Vietnam, Cambodia, Argentina, Guatemala, Indonesia, and elsewhere. In its final tally, anticommunism is responsible for the deaths of millions of people worldwide.

As these and many other abuses of power were revealed, the public became increasingly perturbed. After HUAC, McCarthyism, Watergate, COINTELPRO, and the Iran-Contra scandal, anything seemed possible, and many assumed more explosive secrets must lie in store. September 11, 2001, appeared to validate their gravest fears. The George W. Bush administration made an unprecedented grab of executive authority to battle a nebulous enemy and cooked up a baseless story about weapons of mass destruction to deceive the public into war with Iraq. Brown University’s Watson Institute estimates that over five hundred thousand people have perished as a result of the war on terror, not counting casualties in Syria. As if deception and carnage weren’t bad enough, a movement of 9/11 “Truthers” are convinced something even more diabolical transpired—the destruction of the World Trade Center towers was an “inside job.” There was no limit, some believed, to what the government might do. Bush-era conspiracy theorists, Olmsted notes, were “more interested in making accusations and identifying the government as irredeemably evil than enacting reforms.” The same holds for millions of suspicious minds today.

“The new conspiracism drains the sense that democratic government is legitimate without supplying any alternative standards,” Rosenblum and Muirhead write in A Lot of People Are Saying. They’re correct, but we have to understand the cause. For the last century, anticommunism run amok helped repress legitimate and necessary alternatives, leaving nihilistic reaction and unhinged conjecture to fill the void.

Eight months into the pandemic, a television news station in Kalamazoo, Michigan, broadcast a telling exchange. The newscaster stood in a desolate suburban parking lot, reporting on the reaction to the state’s new Covid-19 restrictions. The owner of a nearby establishment, a weary-looking older man, walked up and told the host he had something to say. He was resisting the shutdown and wanted to say why.

“My government leaders have abandoned me,” he said. “They’ve put me in a position where I have to fight back.” Four trillion dollars of stimulus money was given to special-interest groups and campaign donors, he continued, “enough money to give every family, every family in this country, $20,000 to go home for two months.” If he were given that sort of support, the man said, he gladly would have closed shop and let the virus settle down. “But I’m not going to do it alone.” When asked if he would continue to violate the state order, the man was defiant. “This isn’t a state order; this is a conspiracy, a tyranny … and I’ve got patriots coming out and supporting me.” The eighty-second clip encapsulated the ways government failures fuel conspiratorial thinking. On one level, the man was correct and his indignation justified. When the bailout funds were dispersed in the spring of 2020, a conspiracy of sorts was indeed afoot—bankers and corporate executives made a mad grab for public money with few strings attached, while regular people, who should have been paid to stay home, scraped by on crumbs. But he was wrong to imagine patriotism and a reckless disregard for public health as the solution to a problem caused by plutocracy. After all, the rich can share citizenship status with poor and working people and still dispossess them.

Numerous studies show that insecure, vulnerable, and threatened populations are more susceptible to conspiracism. “Conspiratorial ideation” is driven by both ideology and instability. Feelings of powerlessness, research shows, predict such beliefs. In Republic of Lies, Anna Merlan cites an analysis of letters by readers of The New York Times and Chicago Tribune between 1890 and 2010 that found that conspiracy theories fluctuated in response to times of enormous social upheaval, with the first spike around 1900. Research also indicates that conspiracy beliefs are high particularly among members of stigmatized minority groups. But as Merlan rightly points out, these groups have well-founded grounds for mistrust, given the violent history of white supremacy in this country. Not every community’s sense of persecution is equally valid.

In a perverse way, many prominent conspiracy theories are a cry for justice and connection, even if they frame the world in a Manichaean binary of good versus evil, shunning a structural analysis along with complexity and contingency—positing a cadre of cartoon villains who possess the incredible ability to mastermind world events, leaving nothing to chance. Nevertheless, such theories are typically populist in form, in that they purport to expose the destructive actions of a power elite against regular, unwitting people (a power elite sadly often imagined in ways shot through with anti-Semitism). QAnon’s slogan, “Where we go one, we go all,” often shortened to #WWG1WGA, evokes the Wobbly motto, “An injury to one is an injury to all,” by way of the Three Musketeers. It’s a mash-up of cultural references, stereotypes, thwarted expectations, and dashed idealism. No doubt, many conspiracists are irredeemable racists and authentic fascists, but there are undoubtedly some who would likely be receptive to other messages if they were as omnipresent and aggressively promoted. We’ll never know how many people would prefer the opportunity to have a face-to-face conversation with a community organizer instead of watching a talking head spout nonsense online, because they never get such a knock on the door and a chance to talk. Far from the country of civic associations described by Alexis de Tocqueville in Democracy in America, the U.S. today is a land of anomie where, sociologists observe, a growing number of people suffer from an “epidemic of loneliness.”

The spread of misinformation and fake news has inspired hand-wringing among liberals, who bemoan the public’s gullibility and lack of knowledge. I confess I’ve wrung my hands, too. But it’s not enough to denounce fake news or bewail the inability of regular readers to verify facts or “trust science” (a telling phrase since “trust” is unthinking, an act of faith rather than critical reflection—it means, in effect, know your place). Of course, some people could use a look in the mirror—many liberals spent the Trump years deeply invested in “Russiagate,” which played into dated, xenophobic Cold War clichés about “the Russians” and exaggerated foreign influence while failing to acknowledge homegrown threats to democracy. After all, it was the Electoral College that handed Trump the presidency, not Vladimir Putin. Worse still, liberals came to lionize the very institutions—the FBI and CIA—that have been the primary agents of countersubversive conspiracies, trampling liberties and destroying lives around the world.

As Jonathan Swift quipped in 1721, “Reasoning will never make a Man correct an ill Opinion, which by Reasoning he never acquired.” Ideologies are always shaped by emotions and informed by lived experience. The man in Kalamazoo represents millions who are justifiably angry because they have indeed been abandoned, and who are desperately grasping for explanations that make sense of their circumstances. The challenge is reaching them before mendacious narratives do. But given the right wing’s long and effective assault on labor unions, quality free public education, and nonprofit media—the means and channels through which understanding generally spreads—that is increasingly difficult.

The bipartisan project of undermining the left in this country has been, quite literally, a fool’s errand. By destroying the social solidarity, economic equality, and class conscious worldview that a robust, organized left helps provide, ruling elites have created a vacuum in which unhinged conspiracies propagate. Far from being a rational system as proponents claim, capitalism ineluctably tends toward the illogical and ludicrous. Plutocrats will embrace and promote paranoia as long it is profitable; manufactured lunacy provides useful cover, distracting the public from unpopular policies (tax cuts, attacks on unions, a decimated safety net), just as obsessively naming enemies (Democrats, the press, communists, socialists, antifa, anarchists, feminists, intellectuals, “woke” students, and so on) deflects responsibility and blame. In the memorable words of Stephen Bannon, conservatives counteract the allegedly liberal media by “flood[ing] the zone with shit.” The goal is not to manufacture consent but to promulgate confusion, and digital capitalism expands the arsenal used to assault our senses. (In 2020, videos endorsing false claims of widespread voter fraud were viewed on YouTube more than 138 million times during the week of the election alone; polls soon showed that one-third of Americans believed that voter fraud helped Joe Biden win.) “Those who persistently blame others for indulging in conspiracies have a strong tendency to engage in plots themselves,” Theodor Adorno smartly observed in 1952, and so it goes today.

The world is a complicated place, and we are permeable, interconnected beings subject to infection by ideas and viruses. We are connected across time and space: our beliefs shaped by past events, our bodies impacted by what happens on the other side of the planet, our lungs filled with air exhaled in the next room. Autonomy is an impossibility. Faced with the prospect of this revelation, some recoil, taking solace in revanchist notions of separation, nationalism, and self-reliance laced with magical thinking.

To have a chance of bringing people back to reality, or preventing them from losing touch in the first place, we will need to speak to their apprehensions and misgivings. Consider the growing suspicion of vaccines, which correlates with religious affiliation and higher socioeconomic status, making it one of the preferred conspiracy theories of the comparatively privileged. While anti-vaxxers are a serious threat to public health, there are plenty of reasons to be wary of the medical and pharmaceutical industries. Bill Gates using vaccinations to microchip the masses is not one of them. (Bill Gates blocking researchers from waiving intellectual property protections to make Covid vaccines available to people in poor countries is the real concern.) Or take speculation about the source of Covid-19. The fact is, viruses don’t care about the imaginary boundaries human beings construct, whether those are national borders or the species barrier. Like other zoonotic diseases, the coronavirus jumped from one creature (likely a bat or pangolin) to our kind. It did so because industrial patterns of land use and meat production—picture clear-cut forests, crowded factory farms, and so-called wet markets—push human and nonhuman animals into ever-more intimate contact. In other words, while Covid-19 was not concocted in a Chinese lab or caused by 5G wireless towers, it has political dimensions worth unraveling and discussing, particularly if we want to prevent the next deadly pandemic.

An ancient habit of the human mind, conspiracism will never be entirely stamped out, but it can be diminished if we deprive it of the instability, inequality, and isolation on which it feeds. “We will not be a less paranoid country until we are a fairer one,” Merlan correctly observes. You can’t fact-check people out of a problem that requires collective action, mass empowerment, and clearheaded strategy to solve. Instead of chastisement, we need a credible vision of better society and a recognition that it will take mass movements to manifest it. That means building the one thing nostalgic right-wingers and neoliberal centrists both hate to see—an organized and mobilized multiracial working class fighting for their shared interests. It will take a conspiracy of epic proportions to counteract this country’s ruinous and unrelenting war on people’s ability to come together for the common good, but that’s the only way we’ll all ever be able to breathe.