August 15, 1971, was a fateful day in the history of American economic policy: President Richard Nixon imposed far-ranging wage and price controls on the U.S. economy, abolished the fixed exchange rate system that had been in place since 1945, and took other significant actions to deal with inflation, which had become the economy’s overarching problem. In many ways, we are still dealing with the consequences of those actions.

From 1945 until 1971, the economy of the Western world was governed by a system established at a conference in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, where the victorious powers from World War II (minus the Soviet Union) created rules and institutions designed, above all, to prevent a repeat of the Great Depression. Two principles in particular governed the system. First, there would be widespread free trade (further ensured by the Marshall Plan and the Organization for European Economic Cooperation, now known as the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development). That is because the Smoot-Hawley Tariff and subsequent beggar-thy-neighbor policies were viewed as a root cause of the depression.

Second, the world monetary system was based on fixed exchange rates to prevent devaluations from being a substitute for protectionist trade policies. (When a currency falls in value, imports become more expensive and exports become cheaper in terms of other currencies.) Major nations fixed their currencies to the dollar, and the dollar was fixed to gold at $35 per ounce to provide an anchor for the system. The International Monetary Fund was established to manage this system and deal with fluctuations in currency values resulting from balance of payments problems.

One of the keys to maintaining this system was capital controls. Major nations did not permit the free flow of capital internationally because it could easily destabilize exchange rates. Businesses and individuals had to get permission to import or export capital, and access to foreign exchange by domestic investors or domestic currency by foreign investors was controlled by the central bank. As a consequence, investors were denied the opportunity to seek higher returns in other countries and were forced to invest domestically.

Free-market economists such as Milton Friedman decried the Bretton Woods system because capital controls conferred enormous power on national governments and imposed great inefficiencies on businesses, forcing them to engage in uneconomic transactions to evade the controls. For example, a domestic business could sell goods to a foreign subsidiary at a loss, recouping its losses when those goods were resold in the foreign market, thus obtaining foreign exchange. (This is known as under-invoicing; the same techniques continue to be used by corporations to evade taxes.)

As early as 1953, Friedman advocated floating, whereby market forces would set exchange rates. However, it was feared that this would lead to economic instability that would ultimately reduce international trade and economic growth, and that fixed exchange rates were a brake on the ability of governments to run trade, current account, and budget deficits, as well as central banks’ ability to finance them with money creation. Elimination of these constraints would be inflationary, it was believed.

The emergence of persistent inflation in the 1960s put enormous pressure on the Bretton Woods system as exchange rates diverged from fundamental values. Efforts by Federal Reserve Board Chairman William McChesney Martin to dampen inflation and strengthen the dollar by raising short-term interest rates were strenuously resisted by President Lyndon Johnson. The Great Society and the Vietnam War—dubbed guns and butter—were greatly increasing federal spending and borrowing, and he feared that unless the Fed accommodated this it would result in a recession. Conventional economic theory recommended a tax increase to dampen consumer demand to reduce inflationary pressure, but Johnson resisted this idea.

Finally, in 1968, Johnson supported a one-year surtax of 10 percent on all income tax payments. (You multiplied your regular tax liability by 10 percent to calculate your additional tax payment.) The Revenue and Expenditure Control Act of 1968 took effect from April 1, 1968, through July 1, 1969.

Friedman, an adviser to Republican presidential nominee Richard Nixon, and other so-called monetarists argued that the tax surcharge would fail to curb inflation because the root problem was excessive growth of the money supply. On September 27, 1968, The Wall Street Journal reported that the surcharge “shows many signs of being a flop.” Inflation for the year came in at 4.7 percent versus 3 percent in 1967—an increase of more than 50 percent in the inflation rate.

Despite having promised during the campaign to end the surtax, Nixon was persuaded by his economic advisers to support an extension of it. This was coordinated with Johnson and announced in his last State of the Union Address. In the Tax Reform Act of 1969, the 10 percent rate was extended through the end of the year and at a 5 percent rate through July 1, 1970.

Nixon’s unwillingness to follow a strict Friedmanite/monetarist policy on inflation and to support a tax increase was the first sign that he was moving toward a Keynesian view of the economy. The economist John Maynard Keynes, who died in 1946, was the bête noire of all conservative economists because he believed that an active government fiscal policy (taxing and spending) was the most powerful tool government had to steer the economy. Conservatives universally believed that this led government to become ever larger and was, in any event, ineffective at either stimulating growth or taming inflation.

In early 1971, Nixon admitted publicly that he was indeed a Keynesian: On January 4, he told ABC commentator Howard K. Smith, off camera, that he was “now a Keynesian in economics.” According to The New York Times, Smith was astonished by Nixon’s admission, likening it to a Christian saying, “All things considered, I think Mohammad [the founder of Islam] was right.”

The Times’ principal economic analyst, Leonard Silk (a Ph.D. economist), said that anyone paying close attention to Nixon’s economic policies could have seen that he had been moving in a Keynesian direction for some time. Silk attributed this primarily to Nixon’s intense desire to stimulate the economy through the 1972 election. In his book, Six Crises, Nixon lamented that an ill-timed recession in 1960 torpedoed his presidential race against John F. Kennedy. (Another recession began in December 1969 and ran through November 1970, which gave Nixon an uncomfortable feeling of déjà vu.)

One problem with free-market policy is that it has nothing to offer when there is an economic downturn or any means to stimulate economic growth except do-nothing—the free market always delivers the best growth that is possible, its advocates continually say. Whatever the economic virtues of this philosophy, it is politically untenable; politicians must be able to do something in an economic downturn.

On October 17, 1970, Nixon announced his intention to nominate the prominent economist Arthur F. Burns, who had been serving him on the White House staff, as chairman of the Federal Reserve Board when Martin’s term expired in January. Nixon was very familiar with Burns’s thinking from the Eisenhower administration, in which Burns served as chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers and Nixon was vice president. Therefore, Nixon knew that Burns did not see inflation as primarily a monetary phenomenon.

Just days before the events of August 15, Burns testified before the Joint Economic Committee that he had grown pessimistic that inflation could be contained using traditional monetary and fiscal tools. “Additional governmental actions involving wages and prices” were needed, he said. While decrying price controls as “drastic,” Burns said he would support a Wage and Price Review Board or Anti-Inflation Board to bring pressure on wage and price increases viewed as excessive and inflationary. (This was often called “jawboning.”)

At the ceremony swearing Burns in as Fed chairman, Nixon made it clear that he was being sent there to implement policies that would benefit him. “I have some very strong views on some of these economic matters and I can assure you that I will convey them privately and strongly to Dr. Burns,” Nixon said. “I respect his independence. However, I hope that independently he will conclude that my views are the ones that should be followed.” (Burns’s diary reveals that Nixon called him frequently to offer advice.)

Inflation continued to be a problem in 1971, with forecasts showing an acceleration into 1972, which presented a growing political problem for Nixon. Although inflation was unpopular, so were actions such as higher interest rates to moderate it. Those on the left had a simple answer: wage and price controls. On July 20, 1971, Harvard economist John Kenneth Galbraith, who had helped administer wage and price controls during World War II, testified before the Joint Economic Committee that there was really no choice in the matter because there was no combination of monetary or fiscal policies that could curb inflation without sharply raising the unemployment rate. Continuing, Galbraith said:

There is only one way to have an effective economic policy. That is to leave the monetarists and fiscalists to continue their academic quarrel and recognize that adequate employment and reasonably stable prices can only be reconciled by coming to grips with the wage-price spiral. That requires controls.… The first step in getting an effective economic policy must be a general freeze.

Ironically, Galbraith, who was widely known for being a supporter of Keynesian economics, added that “Mr. Nixon has proclaimed himself a Keynesian at the moment in history when Keynes has become obsolete.” Galbraith thought that big corporations could now charge monopoly prices, which negated Keynesian policies.

Nixon’s CEA chairman Paul W. McCracken was alarmed by Galbraith’s testimony and penned an attack on it in a Washington Post op-ed article on July 28. Wage and price controls would seriously erode personal freedom, McCracken said, and quickly collapse unless the underlying monetary and fiscal sources of inflation were restricted. He was also dubious about the government’s ability to administer an all-encompassing set of wage and price controls.

What really set in motion the actions of August 15 was a demand by Britain to exchange $3 billion of U.S. dollars it held from running a trade surplus for gold. Although American citizens were prohibited from owning gold, the Bretton Woods system permitted governments to do exactly what Britain wanted to do. The problem was that the U.S. had only about $10 billion of gold at that time and had no intention of giving such a large chunk of it to the British. Every other country holding dollars would have instantly demanded gold as well and there wasn’t enough to go around—a classic run on the bank.

Another impetus for action on the dollar was pressure from Congress for devaluation. A report from the Joint Economic Committee advocating it had been leaked to the New York Times on August 8 and gotten a great deal of attention at the Treasury Department.

The Treasury Department had primary responsibility for international monetary policy, and Treasury Secretary John Connally, who had no training in economics and had recently been governor of Texas as a Democrat, took the lead in setting up a meeting at Camp David to deal with the gold crisis. According to recently published research by economists James L. Butkiewicz and Scott Ohlmacher, Connally’s plan had been drawn up by Paul Volcker and proposed that the dollar be allowed to float temporarily until exchange rates stabilized. Since this would constitute a de facto devaluation of the dollar, which was widely viewed as overvalued, it would quickly raise prices of imports and inflation throughout the economy. Thus Volcker advocated a three-month wage-price freeze until a new international monetary regime could be reestablished. Additionally, Connally advocated a 10 percent surcharge on foreign imports to improve the balance of trade.

Secrecy regarding the Camp David meeting was very high. Even the slightest hint of an impending revaluation of the dollar would have sent financial markets into a tailspin. Indeed, the dollar was already under speculative attack just as the meeting began on August 13, intensifying the crisis atmosphere.

McCracken’s top assistant at that time was an economist named Sid Jones. I worked for Jones at the Treasury Department during the George H. W. Bush administration. He told me that he had no inkling of what was happening until McCracken came to him just before leaving for Camp David with a document appointing Jones as acting chairman of the CEA until Monday. Not only had McCracken never done such a thing before; it was highly suspect since Jones wasn’t even a member of the CEA, but only a staffer. Jones speculated that McCracken wanted to be able to say he technically wasn’t chairman of the CEA when the new economic policy was announced.

I am also reminded that I met John Connally in 1980, when he was running for president as a Republican. He gave a speech largely devoted to attacking wage and price controls. I said his points were well taken, so why did he advocate controls in 1971? Oddly flustered by my question, he said there was one unique moment in all of human history when they might have worked and that was in 1971. Connally may not have known anything about economics, but he sure knew the political virtues of appearing bold during a crisis.

At 9 p.m. on August 15, Nixon addressed the nation from the Oval Office, announcing the program of wage and price controls, closing the gold window, and new tariffs on imports. Simultaneously, he issued Executive Order 11615 implementing these policies immediately. Congressional reaction was mixed, but the stock market soared, rising almost 4 percent on August 16. (Businesses thought that the controls on wages would be beneficial, while the constraints on prices were easily evaded; for example through rebates on automobile purchases, which originated during this time and continue today.)

With the inflation problem temporarily under control, Nixon felt free to push Burns to keep interest rates low and continue to provide monetary stimulus, so that the economy would be strong through the 1972 election. Tapes Nixon made of his Oval Office conversations document this pressure.

As everyone involved knew, the controls couldn’t be maintained for long. For one thing, prices on imports and farm commodities couldn’t be controlled. This was especially important regarding the price of oil. Although it was denominated in dollars, the prices of everything the oil producers bought in other currencies rose sharply after the dollar fell. Thus the devaluation led directly to the spike in oil prices by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries in October 1973.

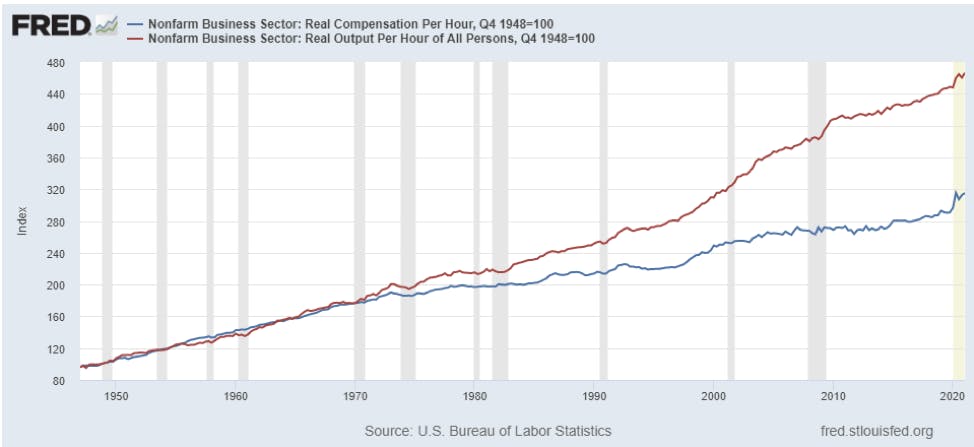

Space prevents a fuller discussion of the consequences of the actions of August 15, 1971. However, I do not think it is a coincidence that the long-term divergence between economic output and worker compensation began almost exactly on that date. Once businesses were free to invest abroad by the abolition of capital controls, which followed from the elimination of fixed exchange rates, workers lost enormous leverage. Globalization destroyed the private sector labor unions and allowed businesses to exploit workers throughout the world, creating a race to the bottom in terms of wages.

Contrary to popular belief on the left, Ronald Reagan’s policies had almost nothing to do with it, and the trend continued through Bill Clinton’s and Barack Obama’s administrations. (Of course, both supported the “neoliberal” consensus that globalization is largely beneficial to the U.S., as does Joe Biden.)

Unfortunately, the option of continuing the Bretton Woods system was not an option, although perhaps it could have been replaced by something better than what we got. The toothpaste cannot now be put back in the tube, and those who say we should return to fixed rates or a gold standard are simply cranks. (Milton Friedman was among those who thought so.) The important thing to remember is that the long stagnation of wages was set in motion by deep international macroeconomic forces that are tied to foreign trade and exchange rates. Those forces changed fundamentally on August 15, 1971, and we are still living with the consequences, which were never envisioned by those who met at Camp David 50 years ago. They believed in their hearts that they were just tinkering, but in fact were opening Pandora’s Box.