One way of interpreting the controversy currently roiling the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) over the relative importance of civil liberties and free speech on the one hand, and the pursuit of social justice goals on the other, is to view it as a conflict between advocates of classical liberal principles of individual freedom and proponents of classical republicanism, which emphasizes pursuit of the common good. In this framing, the civil libertarians want to exalt individual freedom of expression above all other considerations, while the latter insist that the right to individual self-expression must sometimes yield to the greater good of society as a whole. Might it be possible, though, in this particular context, to harmonize these two apparently contradictory ethics?

The ACLU was founded in the aftermath of World War I in reaction to the trampling of the constitutional right to freedom of expression by the administration of Woodrow Wilson, which jailed vocal critics of that war and sympathizers of the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, notably the socialist Eugene Debs. Members of the current American left observing today’s free-speech controversies would do well to note that the ACLU came into being as a protective shield for the constitutional rights of their predecessors in that era.

The ACLU founders, from their liberal vantage point, determined that they were obliged to protect the right to free expression of all actors in the political arena, not just those in their own ideological camp; otherwise, they felt, they would not be true to their overall mission of protecting the precious First Amendment. Furthermore, they would lack credibility with the courts when it came to defending and protecting one of their own. It is this fundamental premise that a new generation of political activists is now calling into question.

As illuminated by journalist Michael Powell’s article on the subject in the June 7, 2021, issue of The New York Times, there are three distinct points of view on this subject within the ACLU itself. First, there is the view of the organization’s Old Guard, those stalwarts of a previous generation who adamantly argue in favor of the traditional purist line. David Goldberger, who successfully presented the case for the right of a group of Nazis to march in the streets of Skokie, Illinois, back in the 1970s, said after hearing speeches from some of the new ACLU activists at a luncheon honoring him: “I got the sense it was more important for ACLU staff to identify with clients and progressive causes than to stand on principle. Liberals are leaving the First Amendment behind.”

Next, there are those who contend it is possible to achieve a reasonable balance between defending the basic principle of free speech and the pursuit of social justice causes. This is the official stance taken by the ACLU in guidelines issued after the fiasco in Charlottesville in 2017, where the ACLU obtained a court order allowing a right-wing group to parade in the downtown area, culminating in a paroxysm of antisemitic and racist expression and the death of a woman counterprotester. The new guidelines suggest ACLU lawyers weigh the importance of any free-speech case involving groups whose “values are contrary to our values” against the possibility it might give “offense to marginalized groups.”

Finally, there are those within the ACLU who scoff at the First Amendment completely, arguing that it is “disproportionately enjoyed by people of power and privilege” and therefore, presumably, of little or no value to others. And Powell reports that some ACLU lawyers believe free speech (presumably meaning disagreement with the organization’s new direction) is now being suppressed within the organization itself.

Nadine Strossen, who served as president of the ACLU from 1991 to 2008, believes that, contrary to all of these single-minded perspectives, free speech and social justice not only are compatible with each other but are actually symbiotic and mutually reinforcing. She has made a powerful case for this thesis in an essay scheduled to appear in the inaugural issue of The Journal of Free Speech Law. Contradicting the supposition that free speech is solely the province of the mighty, she points out that it has rather been the most essential tool for the advancement of the rights of oppressed minority groups throughout all of American history, and that these groups achieved progress not through suppressing the free speech of their opponents, but by countering and overcoming their ideas with arguments more consonant with American ideals and the Constitution. What Strossen is arguing for, in effect, is the complete compatibility in this area of the liberal goal of individual freedom and the republican standard of the public interest.

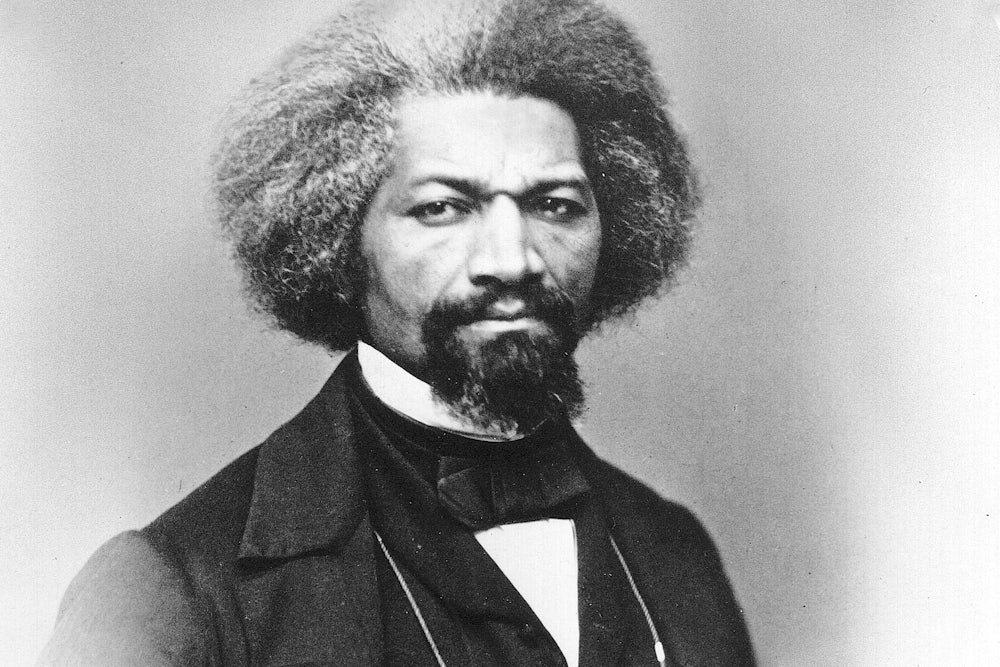

One of the most compelling examples of the use of free speech on behalf of the greater good is that of Frederick Douglass, an ex-slave whose writings and oratory helped inspire the abolitionist movement. Douglass’s views on free speech were unequivocal: “To suppress free speech is a double wrong,” he said. “It violates the rights of the hearer as well as those of the speaker.”

New York Times columnist Michelle Goldberg has speculated that the divide within the left over the value of the First Amendment might soon begin to close as the growing and “multipronged” right-wing attacks on free speech of the left—including those aimed at the promulgation of critical race theory—reawaken its members to how dependent they themselves are on the protections of the First Amendment. She also imagines they might discover as well the importance of the credibility of their potential defenders—the kind of credibility that comes with a record of defending the free-speech rights of everyone, not just of those with whom they are politically aligned at a given moment in history.