For some time now, the Enlightenment playbook of American democracy has seemed to be moving in reverse. Representative government spurns most of the basic demands of representation. The minority party rages against elections that don’t go its way, despite the lopsided advantages it enjoys from the Electoral College, gerrymandered congressional districts, and the Senate filibuster. This fiercely undemocratic faction has openly backed coup attempts and retrospective ballot rigging by any means necessary; it has also embraced legislative sabotage as a governing philosophy. Meanwhile, the major party in government continues largely to behave as though none of this is happening, relentlessly seeking doomed bipartisan accords.

Liberal Democrats remain bewitched by the siren song of compromise for its own sake—the aim that generations of political scientists, lawmakers, and presidents hailed as the unique genius of the American constitutional order. Compromise looks and feels like the sober, grown-up path to authority and judiciously wielded power; it is the premier virtue of pragmatic politics, understood as the art of the possible. Much like the mantra that if one angers the left and the right alike, one has to be doing something right, the fetishized dogma of compromise for its own sake affects an above-the-fray brand of moral self-regard denied to mere partisans on the ground; if only such benighted and excitable souls could understand that compromise was the whole point, why, then this whole grim turn in public life could be scuttled and forgotten, and everything restored to its predetermined golden-mean setting.

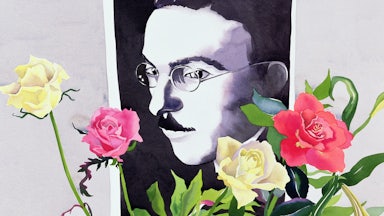

The irony here is that the talismanic faith in compromise has long since come unmoored from the principal virtue most commonly invoked to justify it—rationality. The idea of pursuing a Grand Bargain with a party organized around the principle of blowing up procedural norms at every opportunity is a rank delusion, akin to trying to instruct a feral panther in ballet. Clearly there’s something more to the liberal cult of compromise than the sane, measured grasp of reality it continually professes—and the great virtue of Rachel Greenwald Smith’s essay collection, On Compromise, is to probe the broader allure of compromise in political thought, artistic expression, and pop culture.

It’s not that the phenomenon of compromise per se is inherently suspect, Smith argues; rather, it’s that compromise has become freighted with a host of cultural and moral significations—and thereby drained of any recognizable political substance. Drawing on the political thought of Chantal Mouffe, Smith contends that passionate engagement is at the heart of an expansive democratic politics, and that the cultural idolatry of compromise pushes such engagement—stigmatized, of course, as “polarization”—outside the political realm.

Compromise, elevated into an end in itself, is of course the calling card of the liberal technocratic turn that began in earnest with the rise of the Clintonism in the early 1990s. The resulting de facto division of emotional labor is a disaster, Smith argues:

The problem is that thirty years of centrism, third-way politics and technocratic utopianism have encouraged democratic subjects to believe that significant change is impossible, and that to demand such change is naïve and fanciful. The consequence of this … is that all of the passion has been directed not at politics, but at cultural distinctions, moral judgments, and empty partisanship. Rather than conflicting political goals, we have intractable distinctions: conflicting cultures, moralities, and teams. Paradoxically, the culture of compromise has produced a situation in which compromises have become nearly impossible.

Smith, a literature professor at St. Louis University and the author of a study of the role of affect in neoliberal fiction, tracks this paradox across a wide range of cultural and political settings, from Barack Obama’s infatuation with legislative compromise to the organizational drift of the quasi-anarchist Riot Grrl movement of the 1990s to racially inflected efforts to overcome the complacency and fatalism of compromise as a way of life, such as Paul Beatty’s 2015 novel, The Sellout. Smith also meditates on the nature and reach of compromise in literature qua literature, examining the fiercely uncompromising editorial vision of Margaret Anderson’s model “little magazine” of the early twentieth century, The Little Review, and the contemporary institutions of prestige literature that tout a cultural ethos so open as to be functionally empty. Poetry magazine, for example, was founded around the same time as The Little Review, and trumpeted a nonideological “open door” editorial submission policy that abjures literary schools, among other “entangling alliances”—which works out, in Smith’s view, to a generally ahistorical cultural outlook. Buoyed by a $100 million bequest from an heir to the Eli Lilly pharmaceutical fortune, today’s Poetry has become a flagship of neoliberal literary endeavor; the chairman of its governing board—a Wall Street executive who is also a published poet—endorsed a more robust and experimental editorial approach while also noting how neatly it fit in with the mood of the times: While “predicting the future path of poetry” is like “predicting the stock market,” he wrote in an essay championing the magazine’s growth and new direction, it was also true that “the human mind is a marketplace.”

But as Smith notes, the surface eclecticism of the new lavishly funded Poetry was but a cosmetic tweak of the original open-door policy; citing a letter that African American poet Phillip B. Williams published during last summer’s protests, denouncing the gap between the magazine’s rhetorical openness and institutional practices—and his own complicity in overlooking it for the sake of his own literary prestige. Williams explained how “celebrity, nepotism, and elitism informed the institutional culture of Poetry magazine and the Ruth Lilly Fellowship program, and how those who published in the magazine’s pages participated in and perpetuated that culture in such a way that allowed the foundation nominally to support people of color while keeping its resources from the larger communities to which they belonged.” To break this cycle of tokenist literary reputation, Smith suggests that we need nothing less than a literary revolution encased within a political one. A truly open version of a magazine like Poetry, she writes

would have to be free not only of indebtedness to specific movements or schools, but also the kinds of entangling alliances that emerge quietly under the banner of liberalism, those that reward competition and individual success over a larger sense of collective well-being. And it’s hard to imagine how such a magazine can co-exist with a system that gives some organizations millions of dollars and others none, which is to say that it’s hard to imagine the worst parts of liberalism fading without also the inequities of capitalism fading.

Smith candidly avers that this cultural-cum-political mandate is an “illiberal” one—prizing the collective demands of disfranchised communities over the traditional liberal appeals to individual expression, free speech, and other negative liberties. And her quest for an avowedly illiberal account of political life leads her to some strange alliances of her own, such as the work of the Nazi legal theorist Carl Schmitt, who understood all of politics as a passion-driven division of human communities into (literal) warring camps of friends and enemies. Smith is Jewish, and many members of her extended family perished in the Holocaust, so she does not engage with Schmitt’s thought lightly. While she concedes that a thinker such as Schmitt will “never be my friend,” she cannot escape the implications of his prophecy that deep economic divisions would “turn into a crusade and into the last war of humanity.” “These phrases ring through my head,” she writes, “as I think about all the violence, all the killing, that is perpetuated by the global economic order even if it is never claimed as an act of war, even as no one can define it as a political attack on an enemy.”

What’s implicit in this recognition is the idea that the specter of global economic violence must be met with a corresponding mobilization of the workers of the world to defeat it. But Schmitt’s own career, together with the Schmittian outlook of today’s American right, strongly indicate that the logic of Schmitt’s analysis skews strongly away from any global movement in the direction of social democracy. The cause of “illiberal democracy,” after all, is the slogan of Hungary’s ethnonationalist and antisemitic leader Viktor Orban and his European allies, and the Republican Party is now deeply enmeshed in the Schmittian project of minting ever newer and more vicious culture wars to brand their opponents as enemies of the people. This is a movement that hasn’t blanched before a violent executive-choreographed coup attempt to overturn an election, and continues to propagandize against basic public health measures in the Covid pandemic—an effort certain to result in the deaths of thousands upon thousands more Americans. It is, in short, fully weaponized to conduct political warfare on the model of Carl Schmitt.

It’s also true that American liberalism appears to lack the sort of robust, fighting faith in its own animating mission necessary to shut down this ruinous plunge into political nihilism. The methods it’s reached for on first resort—the Mueller investigation into the 2016 Trump campaign, the pair of impeachments against Trump, and any number of stalled-out congressional inquiries and legislative rebukes to Trumpism—tend to play into the right’s own narrative of liberal governance as an elite, procedural, and lawyerly bid to short-circuit the direct exercise of power on the right. So Smith is certainly right to call out the bloodless, conflict-averse model of political detachment that still prevails in the house of liberalism—the ethos that Barack Obama summed up to New Yorker writer William Finnegan during his 2004 senate run: “A good compromise is like a good sentence or a good piece of music.… Everybody can recognize it. They say, ‘Huh. It works. It makes sense.’”

Huh indeed. It’s telling that Obama invokes the virtues of compromise in aesthetic terms here—as though the primary stakes in the work of legislative were simply a question of maximal formal balance, as opposed to substantive redistributions of power and resources. The real-world impoverishment of this worldview can be readily confirmed by a quick canvas of the bipartisan legislative breakthroughs of the past two decades in Washington, from the Patriot Act and the 2003 resolution to invade Iraq to No Child Left Behind, the TARP bailouts, and the Affordable Care Act—all measures that purchased the appearance of bipartisan comity at considerable harm to the public weal. (The roster of straight-on partisan achievement in Washington is far more impressive and instructive, from the Wagner and Glass Steagall acts to Social Security and Medicare, but that is a political sermon for another day.)

The myopic, aestheticized rationale for liberal compromise is where Smith’s critical outlook comes into play most powerfully. Her book is strongest when she plumbs the distressing ways in which the formalist pieties of neoliberalism prepare the ground for fascist aesthetic sympathies, as when she breaks down the devolution of Proud Boys founder Gavin McInnes from a fully ironized hipster media entrepreneur into a full-on white nationalist. “If neoliberalism substituted market freedom for freedom from structural inequality,” she writes,

the erotic pull of fascist aesthetics may be the consequence of the hollowness of that substitution. Or, put another way, fascist aesthetics emerge because neoliberalism produces, for its most privileged subjects, empty choices, empty freedoms. And the intolerability of living with that meaninglessness seeps into the presumed winners of the neoliberal game, creating a quiet form of misery that one can easily see spinning over into the suicidal logic of fascism.

This key insight, together with many of the other incisive arguments Smith trains on our rapidly fragmenting political and aesthetic landscape, poses a central challenge in the battle for both the liberal soul and the prospects for our democracy. For the crisis of liberalism in our age is as much a crisis of imagination as of institutional support or coherent messaging—and this crisis is compounded by the acute failure of liberal strategists and thinkers to own up to the true proportions of the challenges before us.

Perhaps, as detractors on the left and right increasingly insist, the house of liberalism has grown too rickety, complacent, and unmoored from the crisis of today’s republic to meet that challenge. But as Smith makes clear, the stakes of that failure could not be higher.